Consider this a kind of consumer report. I am not a car gal. I have little interest in vehicles, and the ones that I have owned I’ve driven until their grisly deaths: burst gas lines, generator poof-outs, whole-engine cardiac arrests requiring that the massive mechanical muscle be lifted from the steel cavity and dropped onto a junkyard heap. It is easier, by the way, to dispose of a dead body than a dead car. When my little white Hyundai died at seventy-five thousand miles — died beyond repair or resuscitation — I had to pay a few hundred dollars to have it hauled off to the junkyard on a sunny autumn day, the crisp, clear kind when the sun is so bright the scrap metal glitters and the gutted tires give off the smell of heated rubber. I went along and watched them finish off my car. The Bobcat took one swift bite, and it all came crashing down, with dust and seat stuffing and shattered glass and rainbow streaks of oil dripping from the pile. I was sad to see the vehicle go. I had bought that car brand-new twelve years earlier for four thousand dollars. That car had carried me through my thirties and into my early forties. With it went a lot of good times, a lot of books dreamed up behind its sticky wheel, a lot of crying babies and hauled wood and late-night conversations with my sister, who has since moved to Japan.

I miss my sister. I never imagined she would spend her midlife years in Osaka, eating seaweed and teaching English as a second language. When I first bought my Hyundai, my sister was in her twenties, with long brown hair and her whole life in front of her. Her plan was to get her PhD and teach gender studies in some suave city like Boston, where she could occasionally contribute smart, iconoclastic essays to smart, iconoclastic academic reviews. She did get her PhD, but she didn’t get the college teaching job she had hoped for. In that, she is like most of us: she has achieved what she wanted in some ways, and in other ways she has missed the mark.

She has a Japanese fiancé named Turu, whom she met the summer before my car died. Turu is a businessman. As is common in his culture, he foresees a lifelong allegiance to his corporation. That my sister will marry a man so devoted to bureaucracy seems sad to me, almost as sad as the death of my car.

When my sister first told me of her decision to marry Turu and live in Osaka, she started to cry. We were in my Hyundai. The engine was running. (This was maybe six months before the end, when my car still had some vim, some vigor.) It was a soft spring night, dew glittering on the grass. “You know what I’m most afraid of?” she said.

“What?” I asked.

“I’m most afraid of being buried on another continent. I can’t believe the whole family, all you guys, will be buried here in Boston, and I’ll probably be buried in Japan, with Turu and his family.”

“Well,” I said, “you could have your body shipped back to Boston for burial. That’s not out of the question, is it?”

“But then I’d be so far from Turu!” she said, and she started to cry harder.

This all seemed a little absurd to me, and, at the same time, absolutely apt. “Why don’t you have Turu agree to be buried in Boston with us?” I said. “I mean, you’re agreeing to live your life in his country. The least he could do is agree to do his death in yours.”

“I guess so,” she said.

We were idling in front of her apartment building. “Let’s go,” I said.

“Where to?”

“Blue Shirt,” I said, which is a great cafe near Harvard Square, every wall a different fruit color: mango, melon, grape, green apple. The place pulses with life. The foods are fresh. With every bite of a Blue Shirt meal, you feel yourself getting younger.

My sister is now back in Osaka, a wide and windy continent and an ocean away, a place that feels lonely, a place as seemingly distant from me as death itself. I wish she would come home. I wish I could wake up one night and look out the window and see her flying home over the clouds, borne by my shining white Hyundai, mysteriously resurrected, puff-puffing across the enormous black expanse of sky.

For more than a decade I tracked my maturation by my car’s repair schedule. Every three thousand miles, when it was time to change the oil, I had a teeth cleaning. At thirty thousand miles, when it was time to replace the clutch, I went to see the eye doctor. When the Hyundai hit fifty thousand miles, I hit thirty-five and got my first bone-density test, because my bones have always been thin and brittle. The test came back with bad results. I needed calcium the way a car needs gas: keep it coming. Now that my car was gone, dead, I wondered what was next on my health-maintenance schedule. I was forty-two. Lately I had been seeing a lot of TV ads for burial plots. I thought perhaps I should buy one.

But according to my sister, our family had its own burial plot somewhere in Brookline, Massachusetts. I vaguely remembered that my grandmother, who’d lived to be ninety-six, had been buried in Brookline a few years earlier. I drove out there — not in the Hyundai, of course, but in my husband’s red Jeep, which is astonishingly, aggressively healthy, with its four-wheel drive and humongous tires and hemoglobin color. The graveyard was surrounded by a wrought-iron fence and had a wispy, rusty-looking Jewish star perched on a pole beside its gate. By the time I found my grandmother’s grave, it was nearly five o’clock, and the sun had sunk into a flaming slit and was gone in four seconds flat, the world suddenly yanked back into darkness. I stood there in the desolate Northeast winter evening, by my grandmother’s grave. Sure enough, just as my sister had said, there was a bulging apron of unused land around her headstone, room for half a dozen coffins: my mother and father, my two sisters, my brother, me. But what about my husband, my children? There wasn’t room for them. And did I really want to be buried next to my mother? We don’t get along that well. I decided I would find an alternative.

Still, before I left, I lay in the space I imagined had been reserved for me. This is as morbid as it gets. The ground was hard and freezing. Up above, the moon hung like a yellow earring fastened to a corner of the sky. The air was clear, and the galaxies glimmered, their light millions of years old. I had always envisioned death — or, rather, the transition into it, the last moments, whether on a flaming airplane or in an oncology ward — as fraught and fluorescent, soap-opera-like, saturated with significance: Goodbye, goodbye. But it occurred to me, lying not in my grave but on it, that I might find the process ultimately manageable, even banal, as much a part of ordinary life as leaving for overnight camp, far more dreaded than dreadful. Someday I will die, just like my car. Maybe I will go to heaven and be reunited with my car, but I doubt it. It just might be that the passage is unremarkable, a trip taken, a candle blown, my very last nanosecond spent thinking, This isn’t nearly as scary as I thought. I wish I’d worried less.

Yes.

Of course I have no way of knowing, and when the time comes that I am availed of that information, I will have no way of reporting back to you, I’m sorry to say. I would like very much to write an essay about how it is to die. This would surely win me the Pulitzer Prize for outstanding reporting. But I will never win the Pulitzer. I will never claw my way into the canon alongside Virginia Woolf, just as my sister will never teach at Harvard. This is what midlife reveals: not what you will do, but what you won’t do; not how far you might go, but the limit of how far you can go. Once, I hoped to be brilliant. I hoped to be the female Faulkner. Once, the fact that I was not the female Faulkner was agonizing to me. Now, in my forties, I accept this. I take what I can get. I cherish my oil changes. I am grateful for brakes that work, a brain that works. I may not be a brilliant novelist, but I have become, after a lot of hard work, a writer capable of chugging along, crafting a story with a well-made engine. I write Ford or Pontiac paragraphs: decent, smart enough, but not top of the line. Not even close.

So the death of my car prompted me to find, and then reject, my burial site. It also prompted me to muse philosophically about the passage of time. And at the most mundane level, it prompted me to shop for a new car, because I was still alive, still here, still transportable across the space-time continuum.

Now, buying a new car holds about as much interest for me as buying a new hot-water heater. I began desultorily to search through the classifieds. New? Used? Gently used? Used up? To get a really good car, I saw immediately, would cost me half a year’s salary or more. I could buy a Hummer for forty thousand dollars. I briefly, oh so briefly, considered it. I imagined living my life with a Hummer in my driveway; imagined the shining armor of its exterior, its gargantuan wheels crushing ice and stone, its windows whisper-sliding up and down in their oiled slots. I imagined being so safe, so high off the ground. I wondered: Was I a Hummer gal? Could I become one? Would I have to change my wardrobe to fit a Hummer image? Did a Hummer gal wear sleek outfits with expensive, frothy scarves wound around her neck? Or did she wear Frye boots? But the specifics are not important. What is important is that I briefly considered it. Options unfolded before me like rooms in a dream: I could go Hummer. I could go Porsche. I could go Cadillac or junker or Prius. I could operate on diesel, gas, or electricity. There are many ways to power a motor. There are all sorts of lives.

The day I went to the car dealership, I had a cold, the kind that makes your throat raw and your sinuses feel illuminated on your face, like the person in the old Dristan commercial. With such a cold it seems the skin has thinned, and your interior is exterior, all its flaws and germs exposed. Honking into wadded tissue, I told the salesman, “I need a new car.” This is apparently as ridiculous as saying to a doctor, “I’m sick.” The salesman was sitting in a faux-wood-paneled office, chewing on the pink teat of a pencil eraser. “New car?” he said, with a wicked, slow smile. “Import or domestic? Sedan or hatchback? V-8 or V-6? Manual or automatic?” As he ticked off a long list of options, few of which I understood, I suddenly felt mad. My nose was burning. “Car,” I said. “Tires, steering wheel, seat.”

The car salesman had a fishbowl on his desk, and a bright orange fish swam about inside. The bottom of the bowl was covered in heartbreakingly blue pebbles, so blue it was as though the color had been sucked straight from the sky. There were also a plastic castle and some plastic fronds, which the dumb fish kept trying to nibble. My heart went out to that animal. Its gills pulsated, showing dark shadows beneath its golden skin. On impulse I reached over, grabbed a shaker of fish food, and sprinkled some in. The car salesman looked at me, an eyebrow raised.

“I feel bad for your fish,” I said. “Your fish is having a miserable life.”

“How do you know?” the car salesman said.

Now, this seemed a simple question, but anyone could hear how it reverberated with beliefs about consciousness, the possibility of interspecies empathy, and whether one can ever acquire knowledge beyond the circle of self. “I guess I don’t know for sure,” I said. “But the real question is: Does the fish know?”

The salesman looked in at the fish. He tapped his pink eraser on the bowl. The fish, who was hoovering up the flakes floating on the water, suddenly darted away and hunched at the bottom of the bowl.

“The fish knows,” I said.

Sensing he had a looney-tune on his hands — and perhaps, even better, a looney-tune who had not done her homework — the salesman suggested a car with a strange, African-sounding name, a Yemeni, or something like that: massive, four-door, with a dashboard it would have taken a tech-school degree to operate. I knew as soon as I saw the Yemeni that it was not my car, not my life, but I agreed to test-drive it anyway. I hurt my back trying to get in. (I have occasional sciatica.) When you are in your forties, your back becomes your front. You feel it all the time; it snaps and whistles.

I turned the key in the ignition, and the car did not so much roar as whoosh to life. It was a bright day, our sun, a star in its own midlife, burning in the blue. The car salesman had fastened a license plate that read “JEB11” to the car’s rear end, and I sped down the road, all new and huge, my name not Lauren but JEB11. As JEB11 I felt groundless. I felt like a fish whose bowl has just broken. The glass cracks, and suddenly all the world is yours — if you can breathe in it. As JEB11, I saw that the streets spiraled out across the world, and it occurred to me that, if I wanted to, I could drive and drive. I could steal this car in a snap. I could go to Vermont or Oregon. I could feed any fish I wanted. I could stop writing and become a painter. I could sell houses in Silicon Valley. I could swim with the dolphins and feel their suede gray skin. As JEB11 I understood that, in this day and age, my chances of living another forty-two years are pretty good. (Now I’m sure I’ve jinxed myself and I’ll be dead tomorrow.) I can take testosterone and grow zits and muscles. I can take estrogen and brightly bleed. I can join a gym. I can play the piccolo. I am in midlife, and this can mean the glass is half full.

Bullshit. Pablum like that makes me cackle. (In your forties you start to cackle — at least, I have.) Consider this a warning, all you younger gals, perched on the edge but not yet arrived. My periods come swiftly now, bright and brief. I can feel the ebb and flow of my hormones. I am filled with joy, and then I am sobbing and honking into a crumpled Kleenex. I am speeding down the road as JEB11, ready to remake my world, and then I am exhausted, lying on my unmade bed, listening to my kids quarrel downstairs. What next? I think. Nowhere. Nothing. Noises irritate me. I hate the sound my husband makes when he breathes. The ceiling fan circulates the air with a tiny, high-pitched buzz no one can hear but me. “I can’t stand that!” I say, covering my ears, and then the outside world goes silent, and I can hear only the inside, the surge of my pulse against my palms.

In any case, I did not buy the Yemeni, because I am not JEB11. I decided to look for a used car, one that would allow my kids a college education. Besides, why should I buy a new car when I am used? Shouldn’t your car reflect who you are? Yes. Of course. Buying a car was fast becoming a self-defining experience.

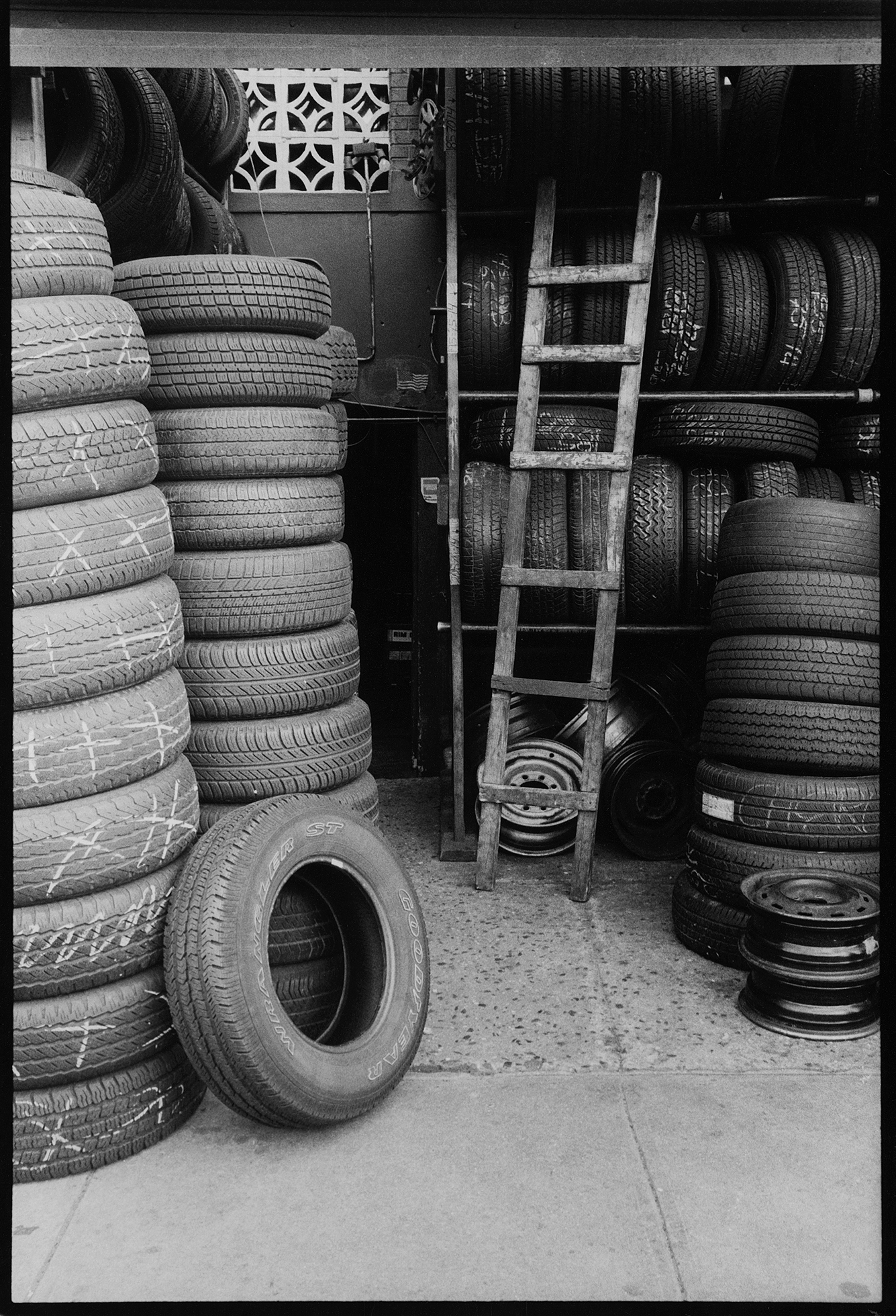

Not far from where I live is a used-car lot with a shack slumped at its edge. A sign on the shack says, “JACK’S.” I’d driven by this place for years, but never once had I considered that someday I might go there. I went there. The cars were so crammed onto the lot you had to squeeze between them. Every sales tag pasted on every windshield had an exclamation point after its price. Each car sported a sporty flag, either red or green, snapping in the wind, lending the vehicles a feeling of animus, as though they might begin to tap-dance on their tires.

Jack was a pudgy, mustached man who spoke mostly Portuguese, which for some reason seemed to enhance our communication rather than limit it. I speak only English, of course. In high school I took German, French, and Latin, and in elementary school I knew Hebrew, but those languages have vanished from my life, leaving barely a trace: a ghostly, half-fogged alphabet. I know this because I recently tried to read a children’s book in German, and practically the only words I recognized were welt and kindergarten. I also tried reading Camus in French, something that had once been a breeze for me, but the little black words squirmed all over the page like parasites. People say that once you learn a language, you retain its traces in your gray matter, a kind of perpetual imprint, a cortical calligraphy. This is not true for me. If my brain ever had a language archive, a little locked trunk where feathers and fantasies and memories and words were stored in an airtight space, that trunk itself is gone now. In midlife things disappear. Whole languages go into the black hole that is your head. If you look at a picture of brain cells, you can see there are spaces between the neurons, little slits, like the trash chutes in apartment buildings.

Jack was saying something in Portuguese and pointing to a teal green, twelve-year-old Subaru, a car that appeared relaxed, like a green lizard snoozing in the sunshine. The sign in the windshield said, “70,000 miles, $3,000!” When I was thirty-three, seventy thousand miles would have been too much for me. Who would buy a car on its last legs? But that was when I was thirty-three, and time has a way of altering one’s values. When I was six, twenty-six was impossibly old. Now that I’m in my forties, seventy is spry. I try to convince myself of this. If there was ever an age at which to learn physics, it’s midlife. All those questions about traveling in a rocket ship at the speed of light, gone for what seems like two seconds, only to return to Earth and find that thousands of years have passed, and you are alone — this is a midlife metaphor. How can time move both so fast and so slow? Why do a feather and a stone fall at exactly the same rate in a vacuum? Does it matter whether I am a feather or a stone if the plunge is invariably swift? I have begun to sense the utter oddity of the natural world. Nothing is what it seems. Stare for a long time at a yellow wall, and it dissolves into thousands of particles. The color yellow itself breaks down, releasing its compressed components of bright white and lime green and purple. The world comes apart, and it is lovely.

This time I did some research. My friend Elizabeth had once had a Subaru and said it was a great car, even though she’d given it up for a minivan. Consumer Reports gave the Subaru its highest rating. I test-drove the car. It had a strange murmur in its engine, but Jack communicated to me that a car murmur is not much different than a heart murmur: “no beeg deal.”

“I want you to change the brake pads, change the oil, get it inspected, check the tires, change all the fluids, and if it pans out, I’ll take it.”

Jack agreed. I left the lot feeling tough and smart. I’d driven a hard bargain. I was not to be fooled.

That night my daughter’s hamster escaped from his cage, and I rescued him by carving through the heating duct with a steak knife and yanking him triumphantly from the jagged hole. Before bed I took out my pastels and used their blunt tips to draw rich blue lines and ocher spirals across white paper. I went to bed happy. I woke up happy. I thought I could draw the sun; I thought I could see its brightness and its darkness all at once. I went to the bank and got a cashier’s check for three thousand and some odd dollars, and then I brought the check to Jack and bought the car.

A new car! Congratulations! For three months I drove it happily. Summer turned to fall. The highway shone before me like a swath of hammered silver. The trees by the side of the road were a deep midnight green, the birds bright flecks in their branches. A hill rose suddenly before me, ascending sharply, at its rounded top a soft smudge of clouds. I climbed and climbed. After three good months, I had confidence in that car. I had confidence until the moment I saw smoke tendrilling out from beneath its hood.

Sometimes things don’t register as quickly as they should. I saw the smoke, but I did not react. Smoke, I thought. I marveled at its purple tinges, its woolly texture. Then, in a snap, that smoke turned black and the car caught fire, a sort of vehicular temper tantrum, coming out of nowhere, spewing vitriol in public. I didn’t have time to be scared. I must have pulled over to the side of the road, although I don’t remember doing so. I do remember yanking the hood release — and the handle breaking off in my hand.

I stood on the side of the road holding the hood-release handle and watched my new used car burn. I was as humiliated as I was frightened. Someone in a passing car must have called the fire department (I don’t have a cellphone), because the firemen came with their tough rubber hoses and smashed the flames flat until all that was left of my purchase was a charred hull, which I had towed. The firemen gave me a ride home. I had never ridden in a firetruck before. I did not feel good about it. The firemen seemed to think the broken hood release was especially funny. One used it as a back scratcher. “Time to get a new car,” they said to me. I picked at the canvas skin of a hose coiled next to me. “That was my new car,” I said.

When the firetruck pulled up in front of my house, all my neighbors came out onto their porches to watch me climb down the chrome steps, helped by a man in a rubber coat and hip-high boots. “Thanks,” I said. I waved goodbye, holding the useless hood-release handle high. After that I wandered around my house for a while, dazed. Then I called Jack.

“Too bad,” he said in what seemed remarkably good English, “but your ninety-day warranty just expired.”

Ninety days. Ninety years. New and not new. Foolish and faithful. Strong and weak. Time flakes down around you. I’d been had. I’d been made a sucker, sucked on, sucked up, and I could not change it. If you were to look at the planet Earth from far away, you would see the blue oceans and the haze of creamy clouds, and you would also see what seemed to be snow, a constant storm, falling not down but up, and you would wonder why a snowstorm was falling up, until you realized that was not snow but souls, thousands of them, dying and rising, swiftly sucked into the atmosphere.

I was mad. Like my burning car, I have a temper. My husband frequently says he refuses to buy life insurance because he’s afraid I might get mad and shoot him for the money. “But, honey,” I have tried to explain to him, “that’s so premeditated. I’m not the type to kill in a premeditated way. I’m more the type to do it on impulse.”

Beware, Jack. I am woman; hear me roar. But the roar was not about gender or women’s liberation. It was a roar into the darkness, the cheapness, and the fire. I went to my closet and put on a suit. I had a plan that I had not really thought out. It had just come to me, an insane plot of the sort that leaves you blinking with surprise in the aftermath: I would dress up like a lawyer and go down to Jack’s slumped shack, disguised, and do something threatening. But what? I zipped up the silk-lined skirt and went to the phone. I called Jack. And for reasons that now seem at once crazy but appropriate, I told him I was an attorney (could I not, at forty-two, become an attorney, a painter, a piccolo player, a Hummer gal?) calling on behalf of her client, Lauren Slater, who had purchased a used Subaru that had exploded into flames. Could have been killed, I said. Faulty hood release. I used words like fraud, negligence, and civil. Jack backed down faster than a fox hearing a gunshot, but I kept on going: damages, deny, defendant, demand. I was learning a new language, knowing all the while the knowledge was easily lost again. Bonjour. Auf Wiedersehen. Shalom.

The next day I went to Jack’s to collect the refund — with damages — that he and my “lawyer” had settled on. I brought my two children with me. I wanted Jack to see that he could have killed them. Looking back on it now, I realize the gesture was melodramatic and insulting, not so much to any one person as to motherhood itself. My kids are not symbols but flesh and blood. Motherhood, like life itself, is never clearly drawn, whereas melodrama always is. I had suffered, but so had Jack, of course. I was a good mother, but I also was not, of course. My kids, in any case, did not cooperate with this ploy. They were obnoxious. Two-year-old Lucas kept trying to honk all the cars’ horns. Six-year-old Clara kept saying, “Let’s get a four-wheel-drive!” Lucas found the water cooler and turned the tap, causing a small flood. I left, check in hand, apologizing for the mess. This is as it should be. I was strong and sorry both.

I am now, thanks to Jack and the combustible Subaru, three thousand dollars richer than I was. I have not yet bought a new car, and I don’t think I’m going to. I think I’ll save my money instead and spend some of it on a gown, or a motorbike, or a trip to Osaka, where my sister is living and dying, eating seaweed and learning a new language that will not replace her old one. For a short time, anyway, she will have two languages. Two ways of talking. Two different words for grief and gladness, old and young, hello and goodbye.

A small portion of this essay previously appeared in the “Lives” section of the New York Times Magazine.

— Ed.