I ’d asked Hella to send me more photographs. Months later she wrote back, apologizing for the delay. “I have looked death squarely in the face most of last year,” she said. “I have cancer but am fighting it with everything I’ve got. This is why I haven’t come up with new work, but I’ll begin again soon.”

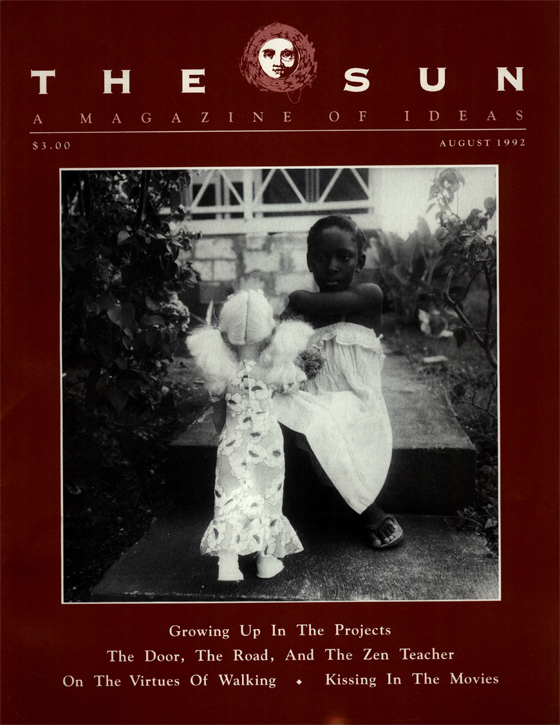

A few weeks later, the photographs arrived: the schoolgirl, in all her innocence and budding sexuality, staring pensively at the camera; the darkened window framed by billowy curtains; the Mexican children in raggedy clothes, dancing in littered streets. The photographs were unmistakably Hella’s: beautiful images that didn’t make celebration a soiled word; that captured the preciousness and transience of life without sentimentality, without turning our mysterious existence into a series of cheap epiphanies, calendar shots.

Aside from the effects of the chemotherapy, she wrote, “life has never been as beautiful. And to think I might have missed this intensity had I not become ill. I am happier than I’ve ever been.” A few months later, more photos. I thought she might be getting well.

So the announcement stung. There was a picture of her holding a bouquet, smiling radiantly. Hella Hammid 1921-1992, the card said. Hella died peacefully at home on May 1, 1992, surrounded by people she loved. A few words, her picture, and — her last gift to her friends — a recipe for “Hella’s Flan.”

I wasn’t a friend, exactly. But I knew a little about her from the lines she sent over the years in response to my requests for contributor notes. “Hella Hammid has been photographing since her teens,” she once wrote. “She has never really decided what she wants to be when she grows up. She lives in a treehouse in California and is thinking about it.” This, from a woman in her mid-sixties! Or: “Hella Hammid wishes to have a camera embedded in the center of her forehead and never again to have to deal with schlepping equipment.” I knew she liked to cook because once she sent me a picture of herself cutting oranges in her sun-drenched kitchen — a woman clearly in love with feasts, with breads and cheeses and curries and jams, with the joys of the harvest and the table. “Be careful,” her recipe warns, after instructing us to let the flan cool. “Very hot.”

I knew that she was born in Germany, and educated in France, England, and the United States; that she had been a freelance photographer for Life, Ebony, The New York Times, and had taught photography at UCLA; that she had photographed such well-known personalities as Anaïs Nin and Benjamin Spock; that her photographs were included in numerous books, including The Family Of Man. Yet, after thanking me for praising her work, she once confessed, “I get discouraged a lot.”

I knew her through her photographs, her amazing ability to capture with the lens what the naked eye often can’t: those elusive, hidden selves in each of us, that company called “I.” Through her images, I knew the secret place in her that children knew, too, so that when she reached out to them, in a gesture as spontaneous and sweet as the wind ruffling their hair, they trusted her — with their sadness, their languor, their mischievousness.

Some of her photographs were controversial. There was the boy playfully pouring water down a girl’s T-shirt on a summer day; a few readers saw in that picture an example of sexual abuse. There was the pregnant woman, her belly swelling like the moon — a heavenly body which, in the minds of some, denigrated pregnancy. Those letters surprised me, though it’s really no surprise that we sometimes see through eyes bleary with pain, narrowed in suspicion, slits that don’t let in much light. Our scrapbooks, full of evidence, prove whatever we want. Yet Hella’s photographs spoke to me precisely because the smiles of children exist side by side with all the hell-worlds, with poverty, with war, with a lifetime of unwept tears.

That she sometimes got discouraged is no surprise, either. We often question even our best work. But in the end, the doubts don’t matter. What matters is that she ran her palm across the grimy pane, looked hard at what was there, what’s only there if you look, if you schlep the equipment up the stairs, set up the tripod and fret about the light, wait for the perfect moment . . . and for the one that’s more perfect still. What matters, finally, are those few adjustments of shutter and aperture, doing the work in spite of the doubts, in spite of that voice that says, forget it, no one cares, you’ve taken enough pictures, we know the face of this suffering planet.

The night she died, in her treehouse in L.A., the city around her was in flames. What did this say about the relevance of her work — of art itself? For a few days, L.A. again became everyone’s picture of the future, overshadowing our private dramas. A camera had documented the beating of Rodney King, yet a dozen jurors ignored the evidence of their senses, demonstrated again that people will impose their own mythologies upon everything they see. We all make a picture of the world, seeing through the soft haze of romance, or moneylust, or power, zooming in on what we want. We set up the shot. Move a little that way, hon. Don’t scowl.

I don’t know what kind of cancer Hella had, how she tried to heal it, what healing is, whether death itself isn’t a kind of healing. I don’t know what it means to suffer that way: to look death squarely in the face day after day, week after week, death leering back at you. What do we know about death when we know so little about life? We think one day we’ll know, yet the years rush by. The photographs, the stories, the dreams, the gurus, the love affairs, the headlines, the fat books of philosophy reveal only so much. This magazine is eighteen years old; when I started The Sun, Hella was in her early fifties. There are people working here who were in kindergarten then. . . . The years rush by, and the veils don’t fall from our eyes.

In Islamic legend, David Black writes, a king sewed up a peacock’s head in a bag so that nothing would distract from the beauty of its tail. The bird forgot what the world was like, assumed that all existence was encompassed within the limits of the bag. Its beauty was beyond its comprehension.

Hella’s photographs were a way of seeing through the bag.

For years, I’ve had one of Hella’s photographs on my bedroom wall. It’s not one of her more ambitious pictures — no one caught in a moment of uncertainty, or reaching out tenderly; none of the living, breathing human faces, our tribe she chronicled so well. It’s another kind of portrait entirely: an empty bed in early morning light, the covers pulled back, the night over, the body gone but its presence lingering.