At midnight I’m still waiting for my name to be called in the Emergency Room at Beth Israel Hospital. My wife, Lauren, is three months pregnant, but tonight we’re afraid she might be having a miscarriage. She’s somewhere in the system now; I have to wait outside.

An hour ago, I stopped a nurse as he unlocked the door to the treatment unit. “Is there any news?” I asked. “Oh no,” he said quickly, in a soft, understanding voice. “The doctors have to run more tests. There are set procedures. It might take two, maybe three hours to learn anything at all.”

If we lose this baby, we can try again. I’m forty-three; Lauren is forty. And we still have a wonderful three-year-old son, Harrison, a luminous presence in our lives. But I’m scared now, and I keep batting away the low voice in my head that says we’re failures. And the more I worry, the more I wonder if worrying itself is a sign of failure.

I remind myself that being upset is natural. The farther along the pregnancy, the greater the sense of loss if problems occur. Three months, lived day by day, is a long time to be pregnant. We have an appointment with the midwife next week, and she says we might even be able to hear a heartbeat then.

We truly want this child. Being parents is one of the best things Lauren and I have done. After years of caring for no one except ourselves, we seem better people for all the extra effort involved in caring for a child.

Besides, we had trouble conceiving Harrison — four years of trying — so we don’t take anything about this process for granted. I remember all those basal-temperature charts, how the line on the graph would slowly creep upward, then sputter out, month after month, year after year.

And let me be honest: at this point in our lives, we’re old enough to have given several ambitions a good shake, and we’re not exactly where we thought we would be by now. Having children somehow helps us feel successful, as if in the eyes of the world we were more valid for being parents — more proven, more acceptable.

I look at my watch. We’ve heard so many horror stories about emergency care in New York City. Is insurance going to cover this? I should know that — I’m a dad. I should make more money. I should be more optimistic.

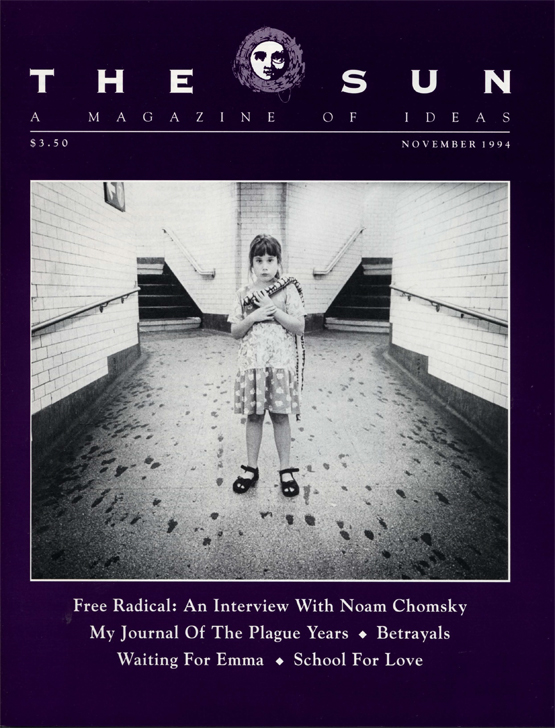

In fact, we’ve always been positive about having another child. We both imagine a daughter: Emma, a real fireball, definite in her opinions and politically precocious. I can even see the birth announcement. It says, “Announcing . . .” in bold type on the cover, then opens up to a color xerox of Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People — that painting of a woman who’s marching over the barricades, one breast bared, with a fearless young kid waving his pistols and a dying old man looking up at her in wonder. I know that sounds odd for a card introducing a newborn, but that’s what I see: woman warrior.

Tonight, though, all I can do is sit and fret, feeling irrelevant, and even slightly envious of Lauren. After all, this event is a part of her; it’s solid and real to her in a way that I’ll never know. So, precisely because I have so little control over the situation, I keep going over the past thirty-six hours, wondering if there was anything I could have — should have — done for my wife.

She called me at my office in Manhattan Thursday afternoon. “So how was the playground?” I asked. “We didn’t go,” she said. “Listen, I’m bleeding, and it’s red — I mean bright red — and it’s getting heavier. Honey, I’m scared.” I felt my own blood slowly leaving my face and arms. “I don’t know what’s going on,” she said, her voice rising over Harrison singing in the background. “I talked to the midwife, and she said to stay in bed and not lift Harrison, just rest if I can. She said what will happen will happen.”

I told her I was coming home, that I’d be there in an hour. I hung up and sat for a moment, trying to think. I write sales literature for computers, and I remember staring at the cover of the brochure lying on my desk, which showed a man and woman in business suits: executive types working at a terminal. He was poised at the keyboard while she leaned forward, reading the numbers over his shoulder, both their faces lit by the glow of the screen — masters of information, calm, productive, and in control.

I stuffed paper into folders, clearing my desk, and banged my thumb slamming a file-cabinet drawer. Then I grabbed my coat and stopped by my supervisor’s office to tell him what was going on. Frank said not to worry, that he’d cover my assignments, and I appreciated his words more than I showed. As I went out the door I was praying, or trying to pray; I don’t believe in a personal God. I do believe in prayer, however; I just don’t know whom I’m talking to. Riding down in the elevator and hurrying out the front entrance, I was making small, spot prayers, asking for help, for direction, for anything, though the words came out dubious and lame. I half walked, half ran to the subway.

We live in Brooklyn, and it took me about fifty minutes to get home. When I walked in the door, Lauren was on the sofa. She looked calm, but she told me she was having cramps — a pain in her lower abdomen, right in the center. She had looked up miscarriage in her medical book, and I read the section she had dogeared: “When pain is severe or continues unabated for more than one day . . . when bleeding is as heavy as a menstrual period, or staining continues for more than three days . . . when you pass clots or grayish material along with blood . . .”

I closed the book and told her I was taking the rest of the week off. Harrison knew something was wrong. He didn’t say much, but he didn’t take a nap. Partly to give him some exercise and partly to give Lauren some rest, I took him to the Third Street playground.

It was a sunny and crisp September afternoon. I felt odd being away from the office in the middle of a weekday. At the playground, I noticed I was the only dad present; the benches were filled with moms and nannies, watching their toddlers and preschoolers.

Harrison climbed up on a play tower, and I sat on a bench where I could see him. This bleeding happens to other pregnant women, I told myself. Their babies turn out OK. I wondered if Lauren knew what I was feeling about her that day. I wondered what I was feeling myself. Like my mother and father, I’m not good at dealing with the stronger emotions, so I don’t always know what’s inside me.

I shifted to keep Harrison in view. “I only looked away for a second! It happened so fast!” say the distraught parents on the evening news. When Harrison was only fourteen months old, he went to the park with a sitter who was trying to manage two other toddlers. Somehow, he wandered away from the park and straight across a busy boulevard where cars travel at forty or fifty miles an hour. Someone saw him and led him back to the sitter, who by then was frantic. We were lucky that time, but in my mind I still see him wandering across three lanes of traffic, cars bearing down.

Harrison waved from the tower, and I waved back. I watched a mom dashing around the base of the tower, playing tag. But no, she wasn’t playing — she was racing: there, about twenty feet in front of me, a baby slowly rolled off the top of the tower, six feet above the ground, and fell as the mother ran to catch her. I covered my mouth with my hand and held my breath as the baby fell headfirst, the mother reaching out. Just as the baby’s head met asphalt, the mother’s arms were around her, breaking her fall. It happened so fast. The child was shaken, but safe. “She was reaching for her egg,” the mother called out to the other moms, picking up a pink plastic egg that had rolled off the platform. She walked back to the sandbox, comforting her daughter, rocking her back and forth.

But I was frozen to the bench, my hand still clamped over my mouth. I looked back to Harrison on the platform as a girl about five years old ran past him. Then bam! she fell down hard on the wooden platform and started to cry. At that point I almost lost it, almost started crying myself because I couldn’t stop seeing visions of children falling, and babies, tiny babies, dropping all over the world. Because that’s what they do sometimes: they fall, they drop, and we try to catch them, try to hold on, but they slip from our fingers, and we lose them, they’re lost.

I took a breath, then stood up and arranged my face. Nothing had happened, I told myself; everyone was safe. I retrieved Harrison from the slide. He didn’t want to go home, but he wasn’t protesting much that day. As I strapped him into the stroller, I promised myself that I’d do my absolute best to take care of them both. It would be difficult, but proceeding deliberately, keeping our balance, we’d make it.

When we got home it was almost dark. Lauren had been talking to our Chinese doctor. He’s a regular M.D., but he combines Western medicine with Chinese herbs. He had a prescription for her, something to fortify the uterus. Lauren told me I could pick it up the next day, but I decided to go that night. That is, after all, one thing a husband can do: get medicine in the night. So I ran around Manhattan, picked up the prescription, got the medicine in Chinatown, and made it back to Brooklyn by eight-thirty, feeling like I’d done my duty. I put Harrison down to sleep around ten, then fixed a sandwich for Lauren and sat with her on the bed. She propped herself up on one elbow and ate the sandwich in little bites, chewing slowly and carefully.

Friday morning I broke open one of the prescription bags and boiled the leaves and roots in a quart of water. The ingredients of a Chinese prescription always remind me of what you clean out of a roof gutter, although the concoctions themselves have a bracing, good-for-you, medicinal taste that I like but Lauren sensibly detests. I boiled the mess down to a single cup of brownish yellow gunk that looked like an oil change and gave it to her. She made a face and forced it down in three hard gulps.

She felt better during the day, but when I returned with Harrison from the grocery store at five o’clock, she was in the bathroom. “I’m bleeding again,” she said, showing me the toilet paper: a bright red smear.

“But a miscarriage is a major event,” I said. “You’d have handfuls, pints of blood, right?”

“Maybe,” she shrugged. “I don’t know. I’ve talked to women who passed black clots for days, and still everything turned out fine.”

She went back to the sofa, and I fixed dinner.

At six o’clock she was still bleeding, and in pain now, cramping. Harrison could tell something was up. He kept pacing around the room, unable to concentrate on anything for more than a few seconds. We called our neighbor Jane, just in case we had to leave Harrison with someone during the night.

By eight-thirty the bleeding had increased — heavy now, with dark clots. Lauren called me from the bathroom. When I opened the door, the toilet bowl looked like it was filled with blood. Harrison burst in, trying to see. “Keep him away,” she said, and I herded him into the living room. A few minutes later, she called out, “I’ve passed something. Get a spoon.” With a slotted serving spoon I fished out a reddish-purplish something I couldn’t recognize and put it in a plastic refrigerator bowl. Lauren sat on the toilet again, but Harrison broke in and tried to climb onto her lap. I returned him to the living room, where I turned on a Mr. Rogers tape; then I went back to the plastic bowl. I couldn’t tell what I was looking at. Was that an eye? A tail? “It doesn’t look like a fetus,” I told Lauren. “It doesn’t look like anything.”

She stood up with one hand braced against the wall. “It’s just flooding out of me, like a faucet.”

“What do you think?” I asked. “We should call Jane and —”

Suddenly Harrison wiggled past me into the bathroom. “I’m the doctor!” he announced. He was carrying his toy doctor kit and he started doing a mad dance around Lauren, prodding her with his little stethoscope.

She raised her voice, trying to catch her breath. “We should call Jane. I’m just getting worse.”

Harrison was spinning around. “I’m the doctor! I’ll fix you! Hold still, Mommy! I’ll fix you!”

“Harrison, honey,” she said, “Daddy and I are talking.” She turned to me. “We’ve got to go to the hospital.”

I called the car service. Harrison ran back to the living room, and I got him dressed. Then he wet himself, which he hadn’t done for months. I changed his underpants and dressed him again.

In eight minutes we were ready. Lauren called Jane and we turned out the lights. As we went out the front door, Harrison gently took Lauren’s hand and said, “Don’t worry, Mommy. I’ll take care of you.” Lauren glanced up to see if I had caught what he’d said. Our incredible, brave child. Finally, the car arrived. After dropping Harrison at Jane’s, we headed for Manhattan. Passing over the Manhattan Bridge, the city looking magnificent and fragile with its million lights, I was thinking, It’ll be OK, Emma. It’ll be OK. Dear Emma McCrea Cole, don’t you worry. . . .

A nurse suddenly calls my name from the admissions desk in the Emergency Room. I’m hoping there’s news about Lauren, but she directs me to the payment window. Behind the window, a woman sits typing at a terminal. We’re separated by a thick slab of plexiglass with a metal speaker in the center, like the visiting room in a prison. I wonder at all this security. How many desperate people have been forced to deal with money and bureaucracy while their friends and relatives might be dying inside? Were some of them told they couldn’t be helped without cash up front or insurance? I lean forward, talking directly into the speaker as the woman enters Lauren’s name, social-security number, and address. She doesn’t seem interested in me, doesn’t even want my name.

Feeling a bit slighted, I take out my wallet and slip my insurance card under the glass. She picks it up, enters the company name and number. I look in my wallet: a Visa card, two American Express cards, a bank card, several ID cards in their plastic holders. What can I do tonight as a man? As a husband and father? Well, I can hand over my cards. I’d rather go off to the jungle and kill a lion to prove myself, but I’m a middle-class man in New York City, and I don’t have a spear; I have cards.

I go back to my plastic chair and wait. Suddenly I miss Harrison intensely. I want to hold him, hug him, comfort him, because that would comfort me, too. I find a pay phone and call Jane. She says Harrison and her son Jeff are sleeping on the futon. “Just like camping!” Harrison told her. Everything seems fine. I go back to the waiting room.

Two hours pass and nothing happens. I begin to wonder how long this night will last. And I wonder if I have the simple strength of heart to manage this life as a husband and dad, helping to raise a family. For the past twenty years I’ve always held a part of myself back from the world because that’s what I thought my precious inner life required; now I’m afraid that I’ve maintained this inner life at the expense of people who need me. I feel like a weak boy, a grad student in high-top sneakers, a would-be poet who can’t deal with being an adult. I don’t want this pregnancy to be over, but what if it is? The very fact that I’m considering this possibility tells me there’s a part of me — a part I’d rather disown — that would be relieved if it were.

Around two-thirty a nurse finally calls my name and leads me into the Emergency-Treatment Unit. I look around for Lauren among the patients. In front of me, an elderly woman is propped up on a bed, holding an ice pack to her temple. Her pale blue dress is splattered with blood. A young Asian man comes up to me and introduces himself as Dr. Zee. He has a firm handshake and a direct, warm manner. His smile suggests optimism. “Your wife’s in that room. We’re just going to do a sonogram,” he tells me, lightly touching my arm, “then you can talk to her.”

A sonogram: then we still have a baby! When our neighbor Jane was spotting, she had a sonogram to see if the fetus was still “viable.” Sure enough, they could see it inside, tiny heart beating away. Now my own heart is pounding.

The doctor comes out smiling and tells me I can go in. Lauren’s lying on a gurney, wearing a green hospital gown. I kiss her. Then she says, “I’m sorry, honey,” and I realize my mistake. It’s all over. “They didn’t tell you?” she asks. “They were only doing a sonogram because I wanted to know absolutely, positively, that there was nothing there, and there isn’t. It’s gone.” We hold hands and talk for a moment. She’s going to have a dilation and curettage; they’ll be preparing her in a few minutes.

In a daze, I wipe away some of the blood and fetch a bedpan. Helping Lauren take off her underwear and tie the hospital gown, I start to have tender, erotic feelings. Her back looks so lovely. Her skin is so soft. I want to say something. I tell her she’s beautiful, and I mean it. (Actually, what I say in my clumsy, what-do-you-expect-from-a-guy way is that she has a great ass — all these curves like a violin. She laughs and shakes her head.) The nurse comes in. I kiss Lauren goodbye, and they wheel her away.

The D and C will take an hour. I’m instructed to wait in the Post-Anesthesia Care Unit, in another wing of the hospital. I wander through a labyrinth of empty hallways, following the signs until finally I emerge into another waiting room, where I sit on a bench and eat an apple.

At four o’clock I talk to Dr. Newman, the Ob-Gyn who has performed the operation. She gently and carefully reassures me that everything looked fine, the procedure was normal, and there’s no reason why Lauren can’t get pregnant again. She helps me put on a paper gown and leads me in to see her.

Lauren is lying in bed. She looks dead. I don’t mean gray; I mean cold, waxy dead. I touch my hand lightly to her forehead. An oxygen mask is clipped to her nose and monitors are taped to both arms. A thimble cap with a little red light is stuck on one fingertip, and wires lead from her bed to a monitor that keeps beeping with a slow, irregular rhythm.

Lauren’s eyes flutter, then open slowly. She tries to speak, and I lean forward. She whispers, “What’s that fucking beeping noise? It’s driving me crazy.”

“That’s your heart, honey.”

“Can you turn it off?”

“I don’t think so. It’s against the rules.”

She makes a little whimpering groan and passes out again.

Around four-thirty Lauren finally manages to lift herself out of bed and into her clothes. She can’t sleep and the monitor is driving her nuts. I’m dubious about moving her, but she’s determined to leave. She takes a sip of apple juice, signs out with the nurse, and we go down in the elevator.

On the main floor, the lobby doors are locked, so we have to go back through the labyrinth again to the Emergency Room. I hold her arm as she shuffles along, head down. I can see two twisted, gray hairs on the top of her head, like my own first gray hairs. Passing an office window, I turn to look at our reflection. I wonder if we’re too damned old to be thinking about babies. At our age, I think, we should be sending kids off to college, not bringing them into the world. Are we not unforgivably selfish and stupid even to be attempting this?

We finally reach the lobby that’s open and I snag a cab outside. It’s a good, fast ride; I tip the driver half the fare. We let ourselves in and Lauren collapses into bed. After setting the alarm to pick up Harrison, I join her.

It’s Monday evening. Two long, quiet days have passed since the trip to the hospital. Lauren is healing, but when she walks around the apartment she still sometimes has to sit down suddenly to catch her breath. She told me that everyone in the Emergency Room said they’d never seen a woman lose that much blood from a miscarriage. For the past two days I’ve cooked and cleaned and repaired things around the apartment. Most of all I’ve gotten up: when Lauren needed a tray, when Harrison wanted an apple, when the phone rang, when it was time to cook. Women do this all the time, but men, most of us, still have a tendency to just sit there. I can’t help thinking that if I’d helped her more, if I’d gotten up instead of letting her be the one to lift Harrison from his crib in the middle of the night (he weighs thirty-three pounds these days), then maybe none of this would have happened.

I wonder how much Harrison understands. Before the miscarriage we told him about the new baby inside Mommy’s tummy, and afterward we told him that the baby had gone away. But he’s been angry with Lauren. She’s betrayed him: since she’s been sick, she hasn’t been able to lift him. He’ll play with her and give her an affectionate pat one moment, then hit her hard the next, a steady, defiant look in his eyes.

Tonight we turn out the lights early, the three of us under the covers, Harrison in the middle. Lauren snuggles against him. “Is Harrison happy?” she asks. He nods slowly, looking away. “Do you remember what happened to the baby?”

No response.

“The baby went away,” I tell him.

Lauren adds, “The baby died. Do you know what that means?”

Harrison nods. “Baby can’t move. He’s dead.” He pauses, then nods again. “Baby can’t breathe. Can’t play. Can’t hold toys.”

“That’s right,” Lauren says. We’re both surprised. She says, “Sweetie, we still might have another baby sometime.”

“Tomorrow,” Harrison says. “Tomorrow is Tuesday.”

“Well, no, not tomorrow. But someday.”

He mulls this over. After five minutes, he hasn’t moved. I pick him up and put him in his crib, then return to our bed. We lie there for a moment in silence. “So what do you think?” I ask. “Do we keep trying?”

She says, “Well, I’m still optimistic. I never had a good feeling about this baby.” (This is news to me.) “Remember that dream I had in August about the rabbis?”

“No.”

“Yes, I told you. I had two dreams, actually, right after we conceived. The first one I never told you about. I was in a garden and I met a woman I recognized. She looked at me and raised her finger and said, ‘This time you really are pregnant.’ Then she turned away. Her robes were pink, so I knew it was a girl.

“But then I had another dream. I was in front of a group of rabbis, and I squatted down and spread my legs, and nothing came out but blood.”

“Well, that was just your body talking to you, which makes sense.”

“But they were rabbis. And all this happened on Yom Kippur.”

“Well, yes, now that you mention it . . .”

“And remember, we went to Beth Israel, a Jewish hospital.”

All this was true. We hadn’t picked out a doctor or midwife at the time, so there was no way to know we’d end up at Beth Israel. She does have potent dreams, that’s for sure.

“So what do you think now?” I ask.

“I’m not sure, but I can feel this weight, like another soul pressing down on me.” She yawns. “And I feel like I’m going to sleep.”

We kiss, and she closes her eyes. I don’t know what to think about what she’s said, but I find myself wondering about newborns, how bright and intricate and unearthly they look. I think about how people in Bali consider the newborn divine and worship it for three months. During that time the infant isn’t allowed to touch the ground. Then, at the end of the third month, in a special ceremony, they place its foot on the earth, and from that moment on the baby is considered a human being.

Perhaps Emma is still on her way, or some other daughter, or another son. All I can do is deliver a minuscule string of genetic code to Lauren and wait. But lying here in the dark tonight, I, too, have a feeling, or rather an image: a soul somewhere out in space, racing toward us across galaxies to this queen-sized bed in a brownstone on Ninth Street in Brooklyn, New York. I might be wrong, but that’s what I have in my head — or wherever thoughts live. What I can do tonight, as a man, is pray for this child. I can imagine it, because imagining is a kind of prayer, too. So as I go to sleep, I keep thinking of a tiny soul approaching, and not casually either, but with all the urgency of a universe unfolding exactly on time, racing toward us at the speed of light.