The daughter lives alone in a little white house in Durham, North Carolina, in a neighborhood without many trees. She waits tables on the breakfast shift at Honey’s, out by the interstate. Late one night, she gets a phone call from her sister: her father has had a stroke; they don’t know if he’s going to make it.

“OK,” the daughter says. “I’ll be up there tomorrow.”

Early on a Saturday morning in August, the daughter gets in her old Volkswagen and begins the drive from Durham to Spring Hill, Virginia, where she was born. She drives fast along the mountain roads, thinking about her father. She doesn’t want him to be alone when he dies. In her mind, she has seen a shadow above his head ever since her mother died. It was then she knew it could happen to anyone: even her father, even her.

The daughter hasn’t talked to her father in maybe a year — not since he told her she was an idiot who’d married an idiot, that he’d known from the minute he laid eyes on him that her ex-husband was a loser. Without her mother there to shut him up, her father said what he pleased. It made her furious, how he thought he could say any old thing and she would have to listen to it. He would interrupt her while she was talking, waving his hand and saying, “Enough.” She decided to leave the old grump be if that was what he wanted. She hadn’t realized until then how her mother had brought out the best in him.

The only time she’s been out of the South was when she went to Vegas with her husband and waited tables while he fixed slot machines. Being married was fun for the first six months, then not much fun for the next ten years. She still thinks of her ex-husband more than she wants to, mostly the bad things, like how he teased her about her size and wanted her to keep smoking so she’d lose some weight. And she’s still a little angry with her father for being right about her ex-husband.

Halfway through Virginia, the daughter stops at the Rebel Diner. It doubles as a country-and-western bar at night. There’s an empty platform in the center of the restaurant where the bands play. She can smell the smoke and beer from the night before. She examines the pictures of the groups that have played there: Kathleen Charnell and the Buckskins, The Kings of Kountry, The Smith Family Singers. They have scared smiles and their faces look like white dough. She gave up smoking for her birthday, but today she lets herself have a cigarette with her coffee. What she misses most about smoking is that first cigarette of the day with the first cup of coffee. Her fingers are stained yellow. She leaves the restaurant before she lets herself have another.

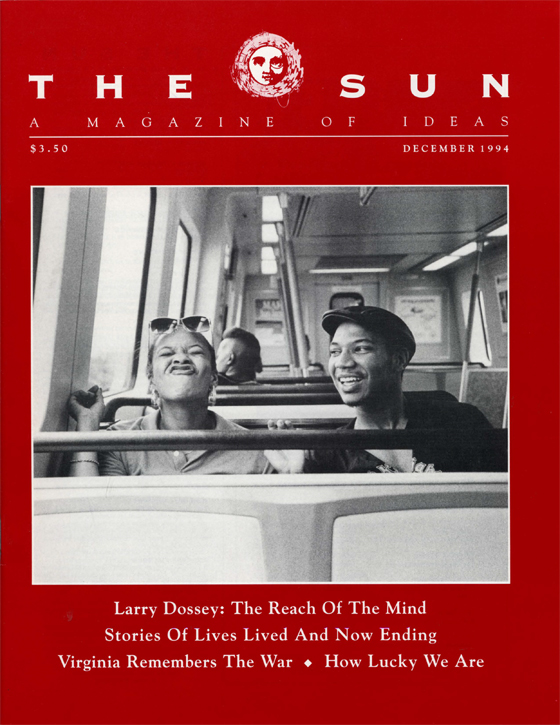

As the day brightens, the daughter drives past historical markers describing battles fought in cornfields, past signs for Appomattox and Manassas, where she used to look for Civil War artifacts with her father. Virginia remembers the war much more than North Carolina does. Cars drive by with “We ain’t fergitten’ ” license plates. She played war when she was little, had both Confederate and Union soldiers’ caps. Her great-great-grandfather fought in the war as a young boy. At home she has a photograph of him looking scrawny and nervous in his baggy uniform.

When she gets to Spring Hill and her father’s hospital room, she finds that her sister has come and gone.

“Hey,” she says, tweaking her father’s toes. “How ya doin’?”

His one good eye watches her walk around the bed. He lifts his left hand slightly. He looks like a baby boy the way the nurses have him turned on his side, curled up in bed. He can’t walk or speak or make much of an expression with his face. He drools.

The daughter settles down in the hard, vinyl chair next to the bed, frightened to see her father this way. “Can I get you anything?” she asks.

He looks at her as though maybe he doesn’t understand. She reaches for his good hand and holds it. There are IV tubes running into his arm. He makes small bubbling sounds when he breathes. She watches him nervously. Is he going to die now? Suddenly he sneezes and scares her to death. Getting over her fright, she laughs at herself, and her father’s eyes open wide at the sound.

Away from the hospital that afternoon, the daughter walks around Spring Hill, narrating her past to herself. Someone has made a lot of money turning Spring Hill back into the quaint little village it never was when she lived there. There’s a historical plaque on the old feed mill where she used to go with her father to get blocks of ice; the workmen would lift them with gigantic tongs. Now the mill is a collection of gift shops and a German restaurant. Behind it is an abandoned railroad track that used to carry the little train they called the “Virginia Creeper.” On the street where she used to live, there’s a renovated house with bloodstained floors. A marker says it was used as a hospital during the war. It stood empty while she was growing up; she shot out the attic windows with her BB gun. The daughter walks by her old house. There’s the dogwood tree from which she shot marauding Yankee soldiers. She sees Mrs. Bynum, who used to give her green apples from her tree. The daughter waves to her. Mrs. Bynum waves back politely, not knowing who the daughter is.

Most of the people in town now are newcomers who commute to work in Washington, D.C. And the old ones who are left wouldn’t remember the same things the daughter remembers: the shot-out windows, the dogwood tree. Theirs is another set of memories entirely. Spring Hill is lonely now with no family to welcome her except her father, who can’t speak.

The daughter makes the six-hour trip through Virginia every Saturday. The doctors say her father is out of the woods, but he can’t leave the hospital. When she gets to Spring Hill, the nurses have her father sitting in his wheelchair, waiting for her, outside the door to his room. He nods when he sees her. She sits with him until it’s time for her to go home again. Who would know if she didn’t make this trip? Not her sister, who won’t come to the hospital anymore. The only news her sister wants to hear is of her father’s death.

During the week her sister calls her from Roanoke and asks, “How’s he doing?”

“Not bad. He sits up in a wheelchair. You should go by. He’d be glad to see you.”

“Oh no, he wouldn’t. The last time I was there, I could tell he didn’t want me around.”

“I bet he was just having a bad day.”

“I don’t see the point of going up there. What difference does it make?”

“It’s a chance to get to know him better before he goes.”

“Shit. He barely even knows you’re there.”

“He knows.”

“I can’t stand to see him suffer like that.”

“He’s not suffering. I think he’s more bored than anything.”

The daughter figures her sister will have to make her own peace after their father dies.

One Saturday in October the daughter stops, startled, at the doorway to her father’s room. The bed is empty. She goes to the nurses’ station.

“What happened to him?”

She’s told her father has been moved to the Long Term Care Center in another wing of the hospital. She finds him sitting in his wheelchair, waiting for her, as always. Because he can’t move the muscles in his face very much, she can’t tell whether he is glad to see her or not. On his lap is something new: a computer keyboard. He types on the keyboard, and at the press of a key, the flat computer translates the letters into a sound resembling human speech. When he sees his daughter, he types:

there is jodie

One of the hospital technicians has programmed a certain key to make the computer say:

hey good lookin’ what’s cookin’

Her father hits that key again and again. The corner of his mouth that still works curls up in a little smile. The computer doesn’t sound very human. It sounds like:

ay oo oo ih ah oo ih

She has to read the liquid-crystal screen above the keyboard to get the joke.

Her father refuses to use contractions when he types. His one working finger hovers over the keyboard looking for the right key, but never aiming for the apostrophe. He types very slowly and doesn’t make mistakes. The daughter pulls up a chair to sit down next to him in the corridor and cranes her neck to watch the little screen. He types:

what is happening to me

what is happening to me

The daughter says, “You had a stroke. You’re going to be in the hospital for a while.”

what is happening to me

Her father doesn’t like the things he used to like. She’s brought him a tape recorder and his favorite tapes — Beethoven and Patsy Cline — but he’s not interested. He motions to her to turn it off. He wants her to talk. She doesn’t know what to say. When she and her father used to visit the battlefields together, they didn’t say much. Mostly they walked side by side, scanning the ground for relics, reading the gravestones.

“Do you remember,” says the daughter, “when the blacksnake and I were wriggling under the barbed-wire fence together?”

Her father shakes his head.

“We were up at the Union cemetery at Ball’s Bluff, and we had to get past this barbed-wire fence. You went over, and then you lifted up the wire for me to crawl under. Neither one of us saw the snake until I was under the fence. You said, ‘Jodie, there’s a big blacksnake right next to you.’ I just looked at it and said, ‘Uh-huh,’ and me and the snake kept on crawling alongside each other. You were real tickled by that.”

Her father types:

go on

“I never was scared of snakes.”

go on

“That’s the end of the story.”

go on

“I’ll tell you another story in a little while.”

Her father has always hated having a television on anywhere near him. In this place it’s the only thing to look at, but he still refuses to watch it. The daughter likes to watch the Redskins. She turns down the volume on the football game until she can barely hear it, but he still types:

turn it off

“They’re in the third quarter. It’s almost over.”

turn it off

turn it off

She leaves it on until the final score. He used to turn the TV off right in the middle of her watching it.

When she goes back to her job, every word she hears she sees typed out in the air in front of her:

i’ll have the breakfast platter eggs over easy

The thing she likes best about her job at the restaurant is going there early in the morning, before anyone else is up. The morning light is pink and cold. The day looks clean. It’s the same way when she starts off on her trip to Virginia. For the first couple of hours, the road is a long gray band leading to a new place. As the morning wears on and she gets tireder and dirtier, so does the day. The daughter is tired most of the time. She can never go to sleep early enough at night to make up for waking so early in the morning.

The daughter visits her father at Christmastime. He lies on his back, his feet pointing straight up under the sheets. The daughter wiggles his big toe affectionately when she comes in. Her father moves his left foot a little and smiles his crooked smile. His laugh has changed. When he was well, it was loud and high; now it’s a husky huh-huh-huh. He laughs when she shows him the bright red baseball cap she has bought him for Christmas. She perches it at an angle on his bald head.

“You look real sporty. Want to go for a spin?”

The daughter wheels her father all over the hospital, past the maternity ward and the emergency room and the chapel.

where are we

Next to her father, she feels large and heavy. Her father used to be a big man. Now she can lift him out of his wheelchair by herself. She pulls him up on his feet and tilts him back into his bed. In the room just past her father’s, another man who has had a stroke screams, “Fuckin’ nigger! Fuckin’ Jew!” The nurses tell her he was a nice man before his stroke. Now it’s as if the words he’s been holding back all his life are coming out. After she gets her father settled into his bed, the daughter walks by the screaming man’s door to see what he looks like. He’s smiling sweetly as he hollers. The daughter hopes everybody won’t know her secret thoughts when she is old.

Other sounds come from the hallway:

“Bbrrrroooooooaaaaaaawwwwwww!”

“Hi baby, hi baby, hi baby.”

“Bbrrrroooooooaaaaaaawwwwwww!”

The daughter has gotten so she hardly hears them.

In early February, the daughter picks up a sandwich on the way to the hospital. She eats it next to her father’s bed. While she’s eating, a nurse comes in and pours liquid nutrients into the bag that leads to the tube that leads to his stomach. Her father burps. He types:

what is that

“Hot pastrami on rye,” the daughter says. “Can you smell it?” She waves the sandwich under her father’s nose. He shakes his head. His eyes watch her face.

“Bbrrrroooooooaaaaaaawwwwwww!” comes from down the hallway. The daughter and her father act like they don’t hear.

“Fuckin’ nigger! Fuckin’ Jew!”

The daughter doesn’t look at her father when they hear that. Her father types:

such bad language

“Hi baby, hi baby, hi darlin’, hi baby,” says Marlene, who is being wheeled past the room’s open door.

Her father hits the key on his computer:

hey good lookin’ what’s cookin’

Marlene waves from her wheelchair, and he lifts his left hand ever so slightly.

Marlene worked in the kitchen of the high-school cafeteria while the daughter was there. The daughter remembers the other kids calling her a “he-she.” Marlene had black hair on her legs. She wore white ankle socks and had a blurred tattoo on her forearm. From the study-hall window, the daughter would see her smoking outside the kitchen door, next to the garbage cans.

After their lunch, the daughter watches her father sleep. He snores softly. When she was little, she would hear him snoring in his bedroom at the far end of the hall. The sound of his snoring meant that his day’s work was done. Her father loved work. He talked about it as though it were a solid thing, and a picture of it grew in the daughter’s mind: work the color of lead and just as heavy. Work was putting your head down and pushing with your shoulder until you got through it. That’s the way the daughter feels about his illness: it’s the work they must get through.

Her father was a turkey farmer. He worked fourteen or sixteen hours a day for most of his life. When the farm failed, they had to move into town, where her father got a regular job that ended before sunset. In the evenings, he wandered aimlessly from room to room in their new house, looking for work to do. The daughter missed the farm, too. She’d loved hunting for eggs the turkeys laid in the fields, following cow paths down to the brook behind their house and playing in the water, catching minnows and salamanders. The daughter wanted to run away with her father — away from her mother and sister, who were always telling them what to do, away from all the houses too close to them. She wanted to camp in the woods with her father and live free. Instead, they kept on living in the house in town, occupying themselves by going to Civil War battlefields to read the inscriptions and look for relics. They spent Saturdays retracing the battles of Ball’s Bluff or Bull Run. They found musket balls together; she would run to him over the cut-grass field, clutching the round, rusty iron in her hand. “Lookie! Lookie!”

“Wow!” her father would say. “That’s great!”

The dead lay asleep under the grass, beneath little white tombstones. “It was an awful waste of young men,” her father would say. The daughter would run her fingers over the letters, blurred by lichens and time.

Her father’s roommate is an old, old man. His lower lip hangs down. He sits on the edge of his bed and talks constantly to himself: “What do you mean? No, I ain’t. I ain’t a-gonna do that, and no I am not sorry, neither. I didn’t hurt you — you hurt yourself. You leave me alone, you.”

Her father wakes up and types:

he has too many regrets

The daughter walks down the hall to go to the bathroom and to get away from the roommate.

“Hiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii,” says Marlene, grinning crazily.

“Hi,” says the daughter.

Marlene grabs her hand, still smiling hard, and says, “How you, sweetie?”

“I’m fine. How are you doing today?” The daughter wonders how Marlene can still have calluses when all she does is sit in the hospital.

“I’m all right now. You take mighty good care of your pa. You a good girl, you.” Marlene looks exactly the same as when the daughter was in high school. She wears her greasy black hair slicked back and has a mole on her chin. She still has black hair on her legs and white socks.

The daughter gently withdraws her hand from Marlene’s grasp. “I’ll see you later.”

“OK, honey. You a good girl, you. Yes, yes.” Marlene wheels herself away.

In the spring, the daughter drives to the hospital through mountains sprinkled with the deep pink of redbud trees. She pushes her father’s wheelchair into the day room. Sarah Lowell is there, sitting next to her husband, who is bent over in his wheelchair, drooling a thin line of spittle. Sarah waves little baby waves at the father as though he is a child.

“Hey, Pete. Hey, Jodie. You look real good today, Pete. Doesn’t he look good, Jodie?”

The father types:

she should shut her trap

Sarah says, “What’d he say?”

The daughter says, “He wants to know how Raymond’s doing.”

“Well, last night he didn’t sleep too well, and he’s a little cranky. Doesn’t want to listen to anything I tell him. I think he’s taken a turn for the worse. The doctor says he might have had a seizure yesterday.”

Sarah comes here every day for eight hours. Visiting Mr. Lowell is her job. Sarah doesn’t read, or knit, or even watch television; she sits next to Mr. Lowell and waits for him to want something. The daughter and her father always visit the day room now, and Sarah tells her the details of Mr. Lowell’s progress during the week, from bowel movements to coughs to small seizures.

One weekend, the daughter is very surprised to find no one in the day room. Her father types:

where is sarah

Later, when she wheels him back to his room, they find out that Mr. Lowell has died.

Her father searches for the right keys on his computer.

i have had a stroke

“That’s right,” the daughter says.

i will not get well

“You might. You’re a whole lot better than you were.”

Her father shakes his head.

i will not get well

“I guess you just have to play the hand you’re dealt.” That is what he has always told her to do.

The nurses tell the daughter that her father looks forward to her visits, that he sleeps most of the week but pulls himself together for Saturday morning. The daughter feels like a fake when she talks to her father; the things she says could be lines in a soap opera: “You just have to play the hand you’re dealt”; “You’re looking better”; “I love you, Dad.” Maybe she doesn’t mean them. She hears herself talking as if she were reading a script. She hasn’t cried yet over what has happened.

It’s a beautiful spring day. The daughter takes her father out of the hospital and wheels him down the narrow street that leads to the cemetery. Her father turns his head this way and that to look at everything around him. The cemetery is where her mother is buried. She pushes him up the long hill that leads to her mother’s grave.

“That’s where Mama is,” the daughter says. The father starts to moan. They stay there, a little ways from the grave but as close as the cemetery road will take them, while her father cries loudly, like a dog in pain. She stands behind him, holding on to his chair. After a while, he grows quiet. “Do you want to stay here any longer?” the daughter asks. He shakes his head. She rolls him back to the hospital past lilacs in bloom. She wishes she could cry like that.

On a Saturday in the middle of the summer, the unhappy roommate isn’t there anymore. Whether he has moved or died, the daughter doesn’t know. She sits on his empty bed and reads a magazine while her father sleeps.

It has all come down to this: this silent room, the whisper of oxygen tanks, the drip of IVs and catheters, nurses walking by in big, white, silent shoes. One nurse says she sings “Amazing Grace” to the father every evening. He used to be an atheist. The daughter doesn’t know what he is now.

The hospital is like a drug. The daughter wants to lie in the empty bed and be like her father, with nothing to do but digest the liquid food being poured into her stomach through a tube in her nose. She’d like to lie there instead of going back to the restaurant and waiting on strangers all day long and coming home to no one in the evening.

When the time comes, the daughter walks out of the airless warmth of the hospital into the hot July sun to go home. The heat grabs her like a hand. She feels as though she’s about to faint. The air is thick and fragrant with the smells of grass, pine straw, the hot asphalt of the hospital driveway. She stands confused in front of the hospital entrance, and for a moment, she can’t remember where home is.