Robert and I went our separate ways, and by the end of that summer, I had settled into a new routine. But discontent pervaded my waking hours, and a sensation of emptiness haunted my dreams.

For weeks, I had dreams of Robert, sometimes pleading with me, sometimes shouting, but always standing just far enough away that I couldn’t reach him. When I woke, all I could think of was my refusal to let him touch me for months before we broke up, of how I’d felt myself flickering like a dying candle with him providing the gentle yet killing wind.

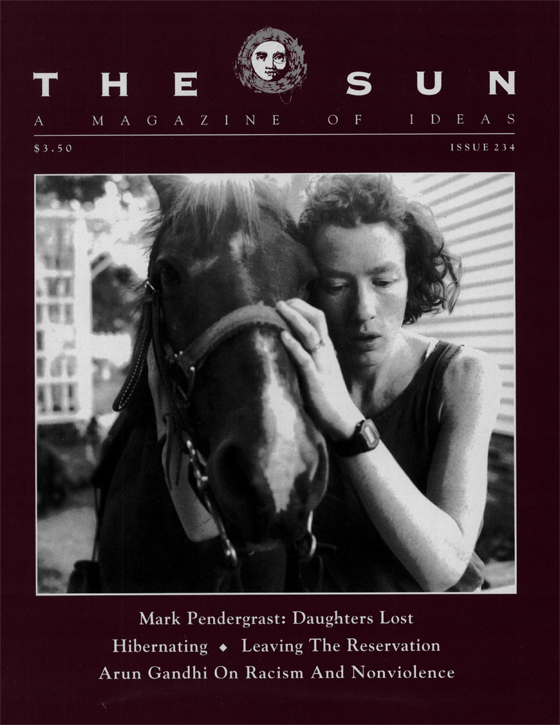

Then came the dreams of animals. At first, I walked among them and slept on the bare ground. Then I became one of them, powerful and sure. I lunged at shadows in rivers, dug in the earth, and overturned boulders to find food. . . . And then I stopped remembering my dreams altogether.

I’d go to work, and for the first couple of hours I’d feel fine — but then I’d long to be elsewhere and alone. I became unsociable. I had nothing to say to anyone. My stomach felt like a hollow cave. My nails grew long.

Still, colleagues smiled at me and praised my work. I was freelance, under contract through the spring with the possibility of staying on if things went well. The boss took me out to lunch the second week, around the time my teeth started hurting. I thought soup might be the best choice, but ordered venison in juniper sauce instead and chewed till the pain was gone.

The itching was the worst part. I finally consulted a dermatologist, but he found nothing. “Are you under a lot of stress right now?” he asked. “Not really,” I said, reaching up in my armpit and gouging at it with my nails. I started to say something about my dreams, but then remembered they weren’t his field.

On the Monday before the equinox, I left work at noon to feel the autumn sun and to buy fish at the public market. Eyeing a fifteen-pound white king salmon sprawled on the ice above a row of smaller fish, I lied to the fishmonger, telling him I was feeding eight people. Hefting the salmon under my arm, I headed back to the office.

Not a hundred yards from the building I caught a scent — somewhere beneath the creosote-and-seaweed smell of Elliot Bay — that turned my head. It wasn’t the homeless man in the doorway behind me, his clothes so dirty and old they looked like shredded skin. It wasn’t the boxwood in the sidewalk planter, the pizza parlor, the bakery, the stale beer from the tavern, the diesel exhaust — none of these.

It was bear shit, suddenly familiar and evocative. A pile lay steaming on the doorstep of a boarded-up hotel. I felt hot iron in my legs and pretended to fumble for something in my pocket as I crouched in the doorway and inhaled deeply. My eyes stung with the pungency of spruce and coming snow, the soft earth and the hundred rich scents of the autumnal forest. Checking to see that I wasn’t watched, I unwrapped the salmon, laid it gently beside the mound, and walked away.

The next day, when I passed by that same spot, the doorstep was empty but for the bones of the salmon.

At the office, I gazed at my maps with their red lines of roads thrust through valley bottoms, and bright swaths of green where animals walked. My body felt clean and empty.

As weeks passed, I experienced a creeping fear that I was out of my mind. At work, arguing with a colleague, I warned him, “You’d better listen to me — I’m bigger,” though he outweighed me by at least sixty pounds. I felt squeezed as I walked down the halls and I routinely knocked things over. My office door stayed closed now, provoking resentment and rumor.

Around that time I ran into an old friend outside the library. Leaning against a newspaper box, I nodded heavily as she exclaimed, “You’re growing your hair out again!” I felt a twinge of jealousy at her simple humanness, her bright voice. She asked about Robert, expressed sympathy, asked how I was doing. “I feel winter coming on,” I said.

I spent lunch hours sleeping on the grass at the park a block from my office. A vagrant woke me one day to tell me he’d never heard a woman snore like I did. He imitated me, lying on his side with his hands under his head and a bottomless rumbling in his throat.

And I spent long evenings curled up on the couch, too tired even to scratch my fiercely itching scalp, listening to the sound of my breathing and my heart; I took my pulse: fifty-eight beats per minute. Dreaming of meat, roots, and succulent ants, I ate little and lost twenty pounds; but my muscles grew solid on sleep and fearless nocturnal walks through the park. My cat became somewhat afraid of me, but the sleeping made complete sense to her.

In November I went incommunicado. Friends worried, then gave up. The only friend I still spoke to was Callia, who lived ninety miles away. I knew she understood, as she had dreamed herself into a deer years ago; she still possessed the authority of a five-point buck and the grace of a doe. We planned a visit, and the following weekend spent a peaceful day sleeping in the park, she curled up in a bed of grass, I behind a fallen tree.

Each morning, I donned my human costume and prayed for a miracle of credibility, wondering how much longer this could last; my clothes were wearing thin from the incessant scratching, the hair on my legs showed black beneath my stockings, and the curls on my head grew thicker daily. Yet I continued to work diligently, even reveling in my adaptability, and humored my hidden self by singing to her and tracing ridge lines on the maps above my desk. People spoke to me only when necessary, their nostrils quivering subtly when they did, but I was kind to them and respectful of their vulnerability.

By December, I’d lost thirty-five pounds, yet felt hot in my clothes. I went to Christmas dinner at my parents’ house, and they were shocked by my appearance. I told them I had an intestinal parasite and was undergoing long-term treatment. Later, my dad said, “Well, it looks like you’ve still got your appetite,” as I took another slice from the roast. I grunted deeply, pretended it was a belch, and remembered to say, “Excuse me.” My sister, Sarah, gave me an odd look, then sniffed.

After dinner, I wanted only to sink underneath the table and sleep, but conversation was required.

Mom: “Have you seen Robert? Do you two still talk?”

Sarah: “I always thought you two were going to get married.”

I needed to offer some answer, but the words stuck behind my teeth and pooled there like spit. I surreptitiously scratched and lay down on the floor, pleading indigestion.

Mom: “It’s too bad you couldn’t work things out. Will you be going back to full-time work?”

My molars ached and I scratched again, wondering about dessert.

Dad: “She’s doing OK, Helen.”

Mom: “But, honey, are you saving anything?”

I nodded vigorously, smelling the cedar under my nails. Three months earlier I might have said there was nothing worth saving.

At home, I tore boughs from a dying hemlock and made a bed on my living-room floor. I did nothing but sleep, walk, and eat, talking only during the day and when my mother called. By the end of February, the itching had stopped and clumps of hair came out in the shower.

Then Robert called, wanting urgently to see me. He came by that evening. I remembered to dress. Entering my apartment, he was visibly surprised by the disarray, by the smells I no longer noticed, by my neat little mounds of rocks, leaves, dried berries, and fish bones.

“What’s that?” He pointed to my sleeping den of piled-up boxes, boughs, and blankets.

I laughed and felt power rising in me.

He looked wonderful and uncomfortable, sitting on the couch amid piles of maple leaves I’d brought from the park. They seemed perfectly placed there on the cushions. He must have thought so, too, as he made no attempt to move them.

“I’m getting concerned; I’ve been hearing some weird things. Are you doing OK?”

He seemed so kind and normal. I watched him, picturing us rolling on the floor. There was new warmth under my sinew and hair, a soft roar building at the base of my throat. But then I felt my ferocity gather in upon itself until it was simply there, like the slow heart beating in my chest.

Spring was coming. I slept restlessly, dreamed of fish and glacier lilies, and gained fifteen pounds in my last month of work. I felt a slight urge to heal social wounds, but knew my gorging would be a problem at office lunches. My work was winding down. I kept my office door open now, but no one came in, which didn’t surprise me.

My mother wanted me to come and spend a few weeks with her and Dad when the project ended. Sarah and her new boyfriend would be there, too. “We could all be together.” My ruthless need for solitude was easing, but I stopped short of committing.

On the day my contract expired, the boss took me to lunch again. I knew he was motivated more by a sense of duty than anything else, but I was ravenously hungry and gladly accepted. I ate my steak with the utmost control, chewing like a woman, and restrained myself from eyeing his plate or the waiters’ heaping trays.

He mumbled something about my needing to be “more of a team player,” and I knew I wouldn’t be coming back. I wanted to tell him it was all right, because I had a feeling of sweet release, like a trap’s jaws opening or the soft heave of thawing soil.

I went to see Callia. For two days and nights, we talked, exploring that permeable space between animal dreaming and human life. She was enough of a woman to be safe in the love of this bear, and enough of a deer to understand what that meant. Occasionally, Callia dozed, curled on the floor with dreams of running. As she slept, I walked in the forest by her house, feeling each twig break under my feet and pulling the air into me.

While I didn’t want to leave her, I was called by family obligation. When I left, Callia and I embraced — bear, deer, women, all of us together in a small circle of earth.

I reached the trailhead at dusk and strode toward the creek bed, the hillside, the cave where my family would be.