If you’ve ever bought a car with air bags or received a free airline ticket after being bumped from an overbooked flight, you have Ralph Nader to thank for it. Founder of the nonpartisan watchdog group Public Citizen, he has been an advocate for consumers’ rights and safety for more than fifty years.

Nader rose to fame in the 1960s when he took on General Motors over the dangerous design of its rear-engine Corvair car. His 1965 book Unsafe at Any Speed ignited the debate that led to passage of the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act a year later. Nader also played a role in the passage of the Freedom of Information Act and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. More recently he has fought against unfair trade agreements and corporate welfare and argued in favor of single-payer healthcare. He has run unsuccessfully for president four times, both on the Green Party ticket and as an independent. His recent books include Return to Sender: Unanswered Letters to the President, 2001–2015, Unstoppable: The Emerging Left-Right Alliance to Dismantle the Corporate State, and Breaking through Power: It’s Easier Than We Think. He received the 2016 Gandhi Peace Award, and Life magazine has ranked him as one of the most influential Americans of the twentieth century. His website is nader.org.

Born in 1934 to Lebanese-immigrant parents, Nader was raised in Winsted, Connecticut. His father ran a restaurant and bakery where Nader worked as a boy. (He also had a job delivering newspapers.) Nader was accepted to Princeton University in New Jersey but turned down a scholarship because his family insisted they could pay his tuition and wanted the money to go to someone with greater financial need. He graduated from Princeton in 1955 and went on to attend law school at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After earning his degree, Nader practiced law in Connecticut before moving to Washington, D.C., to work for Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the future New York senator who was then assistant secretary of labor.

Following the publication of Unsafe at Any Speed, General Motors made an attempt to discredit Nader, and he sued the giant automaker for invasion of privacy, winning a large settlement, which he used to found the Center for the Study of Responsive Law. In 1968 Nader and a group of law students referred to in the press as “Nader’s Raiders” produced a critical report on the Federal Trade Commission, the agency charged with protecting consumers from fraud and breaking up monopolies. Nader’s findings led to reforms that reinvigorated the agency, and the success inspired him to found Public Citizen. He would go on to create more than forty other public-interest groups.

For a person of some renown, Nader lives a monk-like existence — renting a small apartment, using public transportation, and wearing the same shoes for decades. He has never married and has no children.

This interview took place in August 2016, several months before the presidential election. Nader and I arranged to meet in front of an audience at the American Museum of Tort Law, the first law museum in the U.S., which he’d founded in 2015 in his Connecticut hometown. (Tort is the legal term for a wrong that causes injury, such as selling an unsafe product or releasing toxic pollution into the environment.) I’d interviewed Nader many times for my syndicated radio program, Alternative Radio, but it had been a few years since I’d last seen him, and he didn’t look well. He was pale, and the left side of his face was swollen from a tooth abscess. As soon as we began to talk, however, he was transformed, and he showed his usual energy and passion during our more-than-two-hour conversation.

I asked him once what energizes him, and he said, “The struggle for justice.”

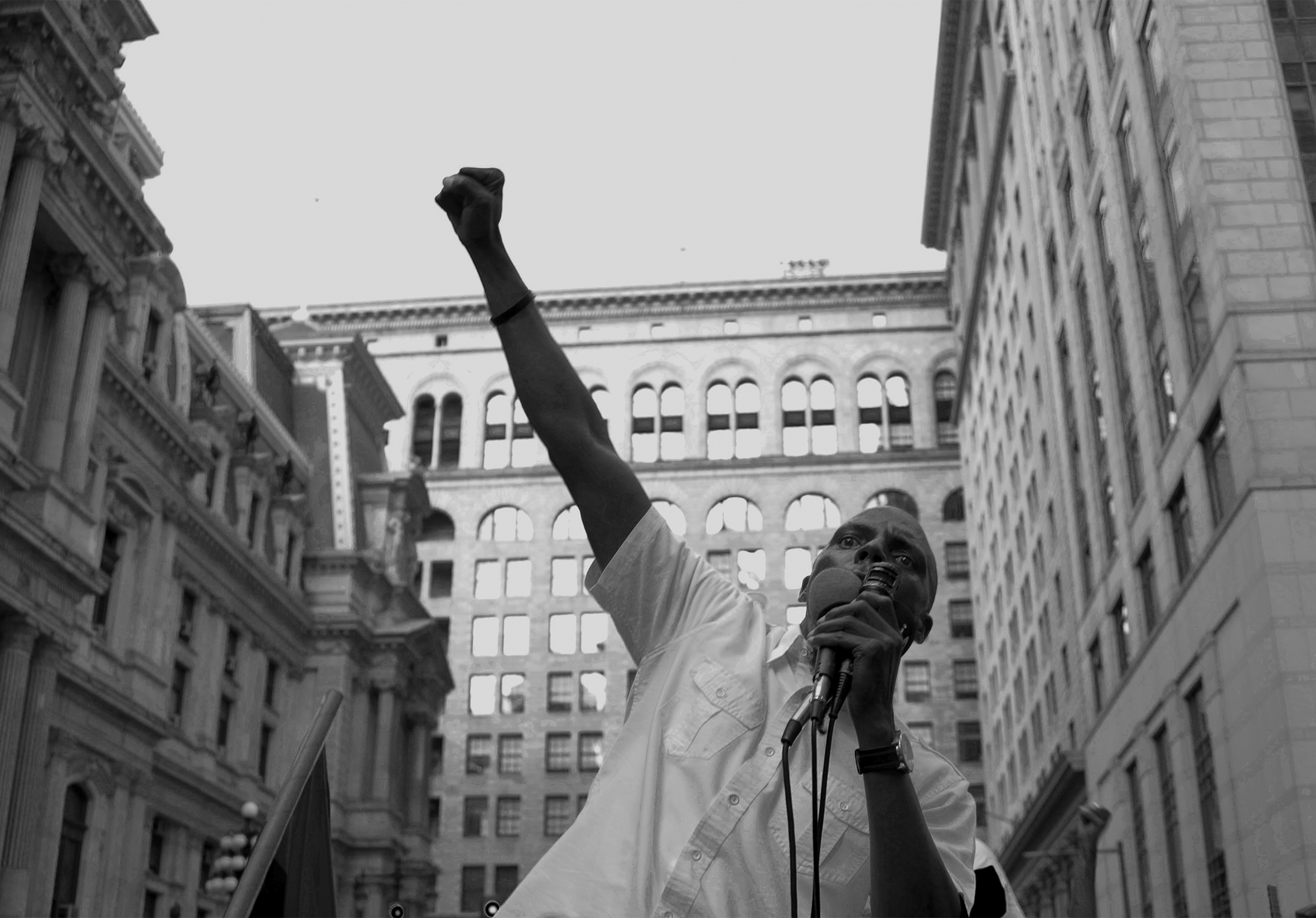

RALPH NADER

© Sage Ross

Barsamian: Let’s start with cars. It’s been more than five decades since you wrote Unsafe at Any Speed, and car problems are continually in the news. There’s the massive recall of faulty Takata air bags; there’s the Volkswagen emissions-tests cheating scandal; and there’s the person who died in Florida in a self-driving Tesla that was on “autopilot.” What’s going on in the auto industry?

Nader: Cars are much safer, more fuel-efficient, and less polluting than they were fifty years ago, but they still have stunning quality-control problems. How did more than 65 million faulty Takata air bags get past the procurement engineers at Toyota, Honda, General Motors, and Ford?

Volkswagen manipulated their software in the lab to meet emissions standards, then used a different software in the cars they sold, which increased dangerous emissions forty-fold. This is outright criminality. You can’t manipulate software by mistake. The question is: How high up in the company does the plot go? Does it reach the president, the CEO?

The fully self-driving car will not be safe enough for the highway. I call the very idea the “arrogance of the algorithm.” There are far too many variables on the roads for the computer to predict them all. And most drivers don’t want it; they want to be in control. But my main concern is that self-driving cars will distract from the safest autonomous vehicles — that super-modern technology called the train. We’re hearing all this hyperbole in the media about robot cars, but we’re not seeing news about public transit. All the razzmatazz about cutting-edge technology is drowning out talk about what we need to invest in to best serve society.

You and I are sitting here in Winsted, Connecticut, population ten thousand. There were once seven trains a day from Winsted to New York City, starting at 7 AM. Now there are no tracks, never mind trains.

Barsamian: There is the much-touted Acela “high-speed” train between Boston and New York, but it’s knocked only about a half-hour off the trip.

Nader: Because the rails are not modern; they’re not able to take the higher-speed trains. We’re not investing in rails as a nation. We’re investing in blowing up Iraq and Afghanistan, in weapons of mass destruction, in aircraft carriers we don’t need and submarines we already have plenty of. This is what an empire does: it bleeds itself dry with military spending. Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize–winning economist from Columbia University, estimates that the Iraq War is going to cost us $3 trillion. Can you imagine what that sum of money could have done for our mass-transit system in the U.S.?

Barsamian: And the Pentagon is chugging along with the F-35 — the most expensive fighter jet ever made — and a new class of Zumwalt destroyers that come in at over $4 billion a pop. How does this persist?

Nader: It’s simple: there are no watchdogs. The Pentagon has a more than $600 billion annual budget. That’s more than half the federal government’s operating budget, not counting Medicare and Social Security, which are insurance systems. And the Pentagon is not auditable. The Government Accountability Office of the Congress completes a budget report every year on all federal agencies and departments except the Pentagon. This is in violation of a federal law passed in 1990 that says all federal agencies have to be audited every year.

More than 90 percent of Americans want the Pentagon to be audited. It lost $9 billion — that’s billion with a b — in Iraq in the first year. No one could account for where the money went. The Air Force buys billions of dollars’ worth of supplies it already has but can’t locate in its many hundreds of warehouses. Yet there’s no audit. We could cut a lot of waste and put the money saved into public-works repair in this country. But do you know how many people in this country are working full time to get the Pentagon audited? I’m not talking about government employees, just citizens or foundation-supported groups. Do you know how many? Zero. Do you know how many it would take to make a difference? Three or four.

When are we going to understand how easy it is to change society? We come up with all kinds of rationalizations: you can’t take on city hall; you can’t take on General Electric; you can’t take on Boeing. We do it to ourselves. Progressives spend plenty of time diagnosing corporate evil — which is OK; I’ve done it a bit myself — but they end up leaving people with a sense of futility, because they don’t show how little it takes to turn it around.

We’re told that we’re a polarized society, right? That’s the way the ruling classes have manipulated people for more than two thousand years: divide and conquer. And, sure, there are differences between the Left and the Right over reproductive rights, school prayer, gun control, and government regulation. But on at least two dozen issues you’ll find combined Left-Right support from 75 to 90 percent of the population. You’ll find it on breaking up the big banks; you’ll find it on civil liberties; you’ll find it on getting rid of corporate welfare and crony capitalism; you’ll find it on criminal-justice reform. Legislators in fifteen states are working across the aisle to pass juvenile-justice reform. There is huge Left-Right support to crack down on the corporate crooks of Wall Street. There are even conservatives who think we’re going batty with empire-building overseas, reckoned just by the deficits it creates.

Barsamian: A poll was recently released that was barely reported in the media. A full 90 percent of respondents said they lack confidence in the country’s political system, and 40 percent described it as “seriously broken.” Equal proportions of Democrats and Republicans — 70 percent — say they are “frustrated” by the 2016 presidential election, and 55 percent describe themselves as “helpless.”

Nader: They know what’s going on. They know the country is being run into the ground, and they’re being run into the ground with it, most of them. But because we don’t learn civic skills in school, we don’t know how to build a community movement and then a national movement. We need adult-education seminars in civic skills. We could offer them at our 1,200 community colleges. I’ll bet there are plenty of civic leaders who would volunteer to teach. But the foundations that might back that effort are run by corporate boards of directors, and with one or two exceptions they don’t want to fund such a project. The government certainly doesn’t want to fund it. They’re too busy shoveling your tax dollars into the corporate coffers in the form of handouts, bailouts, and subsidies.

It all comes down to us. One percent or less of the population in Congressional districts around the country could reverse Congress’s position on most of these issues, as long as that 1 percent represents majority public opinion.

We’ve proven this again and again. The Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act of 2012, protecting government employees who blow the whistle on corporate malfeasance, was bitterly opposed by the corporate lobby. They blocked it for two years in the Senate, but they couldn’t stop it. It passed overwhelmingly. The Freedom of Information Act of 1974 was bitterly opposed by corporate lobbyists and government bureaucrats. They didn’t want openness in government. They liked secrecy. But it passed overwhelmingly. The same with the 1986 amendments to the False Claims Act, which have saved nearly $60 billion by catching contractors who rip off Medicaid, Medicare, the Pentagon, and so on. That was bitterly opposed by corporate lobbyists, but Senator Chuck Grassley, a Republican, championed it in the Senate, and Congressman Howard Berman, a Democrat, championed it in the House. It got through.

Most of the great changes in American society have started with just a few people. Five women in an upstate New York farmhouse in 1848 started the women’s suffrage movement. They didn’t live to see the constitutional amendment that gave women the right to vote, but they set it in motion.

When it comes to civic culture, we’ve been anesthetized into believing that we don’t count, that we can’t make a difference. We basically disenfranchise ourselves and revert to our private lives and try to make the best of it. In the meantime the public problems are smashing into those private lives. Look at student loans: We have the lowest rate of home ownership in fifty years because people who are now reaching the typical age for first-time home buyers are all burdened by student-loan debt — $1.3 trillion worth of it. That’s more than credit-card debt.

This is why Bernie Sanders says we have to have a political revolution. This is why he had such great support, more than he ever dreamed of. When he first announced his candidacy, he polled at 3 percent. But soon he was leading the polls to beat the Republicans — far ahead of Hillary Clinton.

Barsamian: We’ve also got to look at the role of the media and media-generated propaganda.

Nader: Let me tell you about the media reaction when we tried to raise the minimum wage. In 2008 President Obama said the federal minimum wage would be $9.50 an hour by 2011, and then he did nothing. So I went to the mass media in 2009 and 2010 and tried to raise the issue. They weren’t interested.

What made it a national issue, and made more states and cities increase their minimum wages, was when fewer than seventy thousand people — less than the population of New Britain, Connecticut — with the help of the Service Employees International Union, took a few hours of their time to picket Walmart, McDonald’s, and Burger King. Their message was that the federal minimum wage is $7.25 an hour while the CEOs of those corporations make seven to twelve thousand dollars an hour, not counting benefits. The press couldn’t avoid covering the protests because the picketers were blocking traffic into the stores. And then economists started saying that if people had more money to spend, it would create more jobs, more sales, more profits. That’s the way the American economy worked before Walmart took us to a low-wage norm. And then the city councils in various towns looked at the polls and found 75 percent support for raising the minimum wage. That means a lot of conservative workers want it raised, too. When it comes down to where people work, raise their children, and pay their taxes, a lot of ideological differences between Left and Right dissipate. Conservative parents in Flint, Michigan, don’t want lead in their water. They don’t want their kids to be brain damaged. The same holds true for food safety, safer cars and medicines, clean air, and on and on.

Barsamian: Traditional media — radio, TV, and print — are losing audiences to the Internet. Do you see the Internet as a possible tool to get information out?

Nader: It has its pluses, but it’s also distracting. People use it for gossip and games.

Barsamian: And doesn’t the Internet generate a kind of faux activism? Let’s say I forward an article to my sister. Maybe then I think I’ve done my civic duty for today: I’ve sent this article on, and I can go about my business.

Nader: That’s called push-button democracy, and it doesn’t work. When someone tells me, “I got your column, and I sent it to my listserv,” I ask them, “What came back?” Maybe a few thank-yous. There’s too much clutter online. It’s overloaded.

Down the road in Litchfield, Connecticut, there is a reconstruction of the nation’s first law school, which pre-dates Yale and Harvard. It’s called the Tapping Reeve House and Law School. They have a bookcase that is maybe eight to ten feet wide and six feet high. That was virtually the entire law library in this country at the time. If you wanted to learn about the law, it was all there. That’s why the nation’s founders were so well grounded: they didn’t have many books, but they digested the ones they had. Too much of anything depreciates its value.

I once cracked my bat playing baseball here in Winsted. I must have been ten. I took it home and told my dad I needed a new one. He picked up the bat and asked, “Why?” Then he got out some black tape and taped it up and said, “Here. Go down to the school lot and hit another home run.” You don’t think I valued that bat?

Barsamian: Since you’ve brought baseball into the discussion: I listen to sports talk shows on the radio, and I find the callers reveal an enormous amount of intellectual acumen and mastery of detail. When people say Americans are dumb, have no analytical power, and can’t master complex information, I bring up this deep analysis of sports. Why isn’t that same mental power applied to more-meaningful subjects?

Nader: It’s true: when people are really interested in something, they’re very astute about it. Baseball fans know the history; they know the weaknesses and the strengths of the players, the coaches, the managers. They can intelligently second-guess a decision: Should the manager have signaled for a steal from first to second when the player doesn’t run fast and can’t slide well? But almost no one applies the same effort to mastering the rules of Congress.

Here’s an analogy I used in a political novel I wrote called Only the Super-Rich Can Save Us! To be a serious bird-watcher is a huge commitment — the equipment, the details, the coordination with other bird-watchers. And there are about 5 million serious bird-watchers in the U.S. Can you imagine if we had just a million coordinated Congress watchers? It would transform the country. Just a million. It’s easier than we think.

Barsamian: Speaking of fiction, in 1935 Sinclair Lewis wrote It Can’t Happen Here, in which a charismatic man is elected president on a platform of decrying welfare cheats, the liberal press, rampant crime, and promiscuity. He then declares war on Mexico and guts the Bill of Rights. There is a whiff of fascism in the country today, in the scapegoating and targeting of immigrants. Are you concerned about that?

Nader: It’s easy to stir up people’s emotions. Trump has made a big deal out of a Mexican immigrant committing a homicide in San Francisco. Why is he singling out that one homicide among the more than twelve thousand U.S. homicides a year? It’s bigotry, but it appeals to voters whose jobs have been displaced by trade agreements. Their communities have been hollowed out, the jobs sent to Mexico and China and other countries with autocratic regimes where people work for pennies. Trump has manipulated that suffering into an antagonism toward immigrants.

Meanwhile every day in this country about seven hundred people die from medical malpractice, other negligence, or infections contracted in hospitals. Seven hundred a day. Let that sink in. It doesn’t even merit a paragraph in most newspapers, never mind getting on TV. That figure comes from a peer-reviewed study earlier this year done by Johns Hopkins University. They added up a total of 250,000 Americans who die annually from preventable harm in hospitals. It’s not street violence, but it’s violence, and politicians don’t talk about it. Maybe it’s a one-day story in The Washington Post. I found it devastating. Ask yourself: Why is there a massive focus on street violence, but so little news about preventable workplace-related casualties, air pollution, hospital malpractice, and so on? It’s because preventable death isn’t as dramatic. There are stories about street crime on the local TV news every night, but deaths that come from corporate negligence and cutting corners and outright corporate crime are mostly ignored by the press.

We have to start talking to each other and to the press about our friends and relatives who die from hospital infections and environmental cancers and the rest. Because if we don’t personalize it, the law won’t crack down on it.

Barsamian: Gary Younge, writing in The Guardian, says the U.S. is “a country where it’s easier to obtain a semiautomatic gun than it is to obtain healthcare.”

Nader: It’s worse than that. A peer-reviewed study from the Harvard Medical School in 2009 — this was before Obamacare — said that forty-five thousand people die in this country every year because they can’t afford health insurance; their life-threatening illnesses aren’t diagnosed and treated in time. That’s almost nine hundred people a week. Nobody dies in Canada, Japan, Taiwan, Germany, Norway, Denmark, or Austria because they don’t have health insurance — not one person — because they’re all insured from the moment they’re born. But in the land of the free and the home of the brave we allow this to happen. Where the heck is the patriotism? Is it patriotism only when you have a flag and a tank?

Barsamian: Your parents were immigrants, as were mine. What kind of immigration policy would you like to see?

Nader: The first step is to stop supporting oligarchs and dictators who oppress their own people in Mexico, Central America, and elsewhere. For more than 150 years we have propped up oppressive regimes all through Latin America and the Caribbean because they said they were anticommunist or were friendly toward United Fruit or other U.S. corporations. It’s because their citizens can’t support their families that they are coming to this country. What would you do if your government repressed you until you were almost starving, and you didn’t have work, and you had a family to support, and you saw a chance to come to the U.S.? You would take it. That’s where the problem starts.

Number two is to eliminate the demand for cheap labor at corporations like Tyson Foods. Meat processors hire immigrants because they will work for low wages and can’t speak up about workplace hazards for fear of being deported. The conditions for tomato pickers in Florida are almost like slavery.

The third problem is the insufficient minimum wage. When wages are too low, you’re not going to find American workers for certain jobs. If the minimum wage kept up with inflation, a lot of people who are currently unemployed would go back to work. The minimum wage in Ontario, Canada, has been $11.25 [Canadian], and it will soon go above that. If Walmart can make a profit in Ontario paying $11.25 an hour, then it can make a profit in Mississippi paying $10.25 or more an hour.

Those are the three main problems that I see. One other problem is the H-1B visa, which lets in about seventy thousand people a year. It allows U.S. companies to employ foreign workers with special skills. What this means is Silicon Valley corporations — Cisco, Intel, Google — want a special visa for computer programmers from Asia and Africa and South America, and hospitals want visas for doctors from Pakistan or Iran or nurses from the Philippines. Why? Is it because we can’t produce enough nurses or computer programmers? No, it’s because those employers want cheap labor. There are unemployed computer programmers in this country, but they won’t work for what someone from Afghanistan will. So the Silicon Valley lobbyists want to increase the number of people allowed to get H-1B visas to two hundred thousand. I strongly object to that. It displaces U.S. technical workers, and it acts as a “brain drain” on other nations. We are taking the skilled workers from these countries that desperately need their civil engineers, their electrical engineers, their doctors, their nurses, and so on.

Barsamian: The U.S. attack on Iraq and bombing of Syria have generated one of the greatest refugee crises in history. Germany has been relatively generous in accepting refugees. Canada as well. But the U.S. doesn’t have an open-door policy when it comes to refugees largely created by its Middle East policies.

Nader: Canada has accepted more than twenty-five thousand Syrian refugees since December, and Canada has one-tenth the population of the U.S. Obama has let in six thousand Syrians with a promise of four thousand more before the end of the year, and he’s been beaten up for it by the Republicans, who say he’s letting in terrorists — as if the Bush-Cheney invasion of Iraq weren’t a terrorist operation. More than 1 million Iraqi civilians died in that criminal, unconstitutional war.

But there’s something worse: After the end of the Vietnam War, we let in 150,000 South Vietnamese refugees, and more later. We’ve let in maybe 80,000 Iraqis since the invasion, yet many more than that risked their lives working for the U.S. military as translators, drivers, and so on. They’re out there, and their lives are in jeopardy, and they can’t get visas. Why do you think there’s such a difference between Vietnam and Iraq? Because the idea of bringing more Arabs into this country is politically unacceptable to certain interests. They could be Evangelical interests; they could be Zionist interests; they could be pure bigots.

The other argument is “Oh, we have to vet them first.” Well, we do vet them. You would not believe how many steps there are to the vetting process, how many interviews, how many questionnaires, how many polygraphs. It goes on and on. You can reasonably vet a family of six in a few months. Some people have been waiting for six or seven years.

Barsamian: What do you think of the power and influence of the National Rifle Association, the NRA?

Nader: The NRA, to my knowledge, has never held a mass demonstration or march. You know why? Because, like all the most effective lobbies in this country, it focuses on just 535 human beings called senators and representatives. That’s where its efforts begin and end. The NRA knows everything about these politicians: who funds them, what primary challenger they’re most afraid of, who their doctor is, who their lawyer is, who they play golf with, what their personality and character weaknesses are, whether they are susceptible to flattery and like to be taken on junkets. That’s why the NRA is so powerful. Add to that the NRA’s political action committee, which rewards obeisant public servants on Capitol Hill with campaign contributions. And the NRA knows how to punish, too. If a politician stands up to the NRA, it will back a candidate in a primary to try to beat him or her. Members of Congress are afraid of people who are extremely energetic on a single issue. That’s the secret.

Activists usually hold mass rallies against war or climate change in Washington, D.C., on a weekend, when members of Congress aren’t there. All this energy that it takes to put together a rally sort of goes up into the ether. The event doesn’t get that much coverage either, because there are not as many reporters working on the weekend. The activists don’t take up a collection at the rally and raise money to open an office with four full-time employees. With two hundred thousand people, you can quickly raise enough to pay four people’s salaries for a year. Then, when the members of Congress came back on a weekday, they would find more than just a bunch of crushed cups and soda cans on the Mall. They would find four full-time advocates who are connected with a lot more people.

We have to be smarter in the way we lobby. I always say, “Don’t just hope that the government will hear you. Summon the senators and representatives to your town meetings.” We are the sovereign people, and we have to make our hired hands in Congress come to our events and do their homework on the issues. Then we’re up there on the stage, and they are in the audience with their staff. Why don’t more people do that? It’s so much fun to make these politicians squirm.

Barsamian: What’s your understanding of the Second Amendment?

Nader: I don’t spend much time on it. I know the Supreme Court has ruled that it isn’t just about militias; it says individuals have a right to own weapons, but that right may be regulated by the states and by the federal government. You can’t buy a nuclear bomb, for instance. Can you buy an assault weapon? That’s where the controversy lies. That gray area will likely produce more lawsuits that go to the Supreme Court, but unless somebody comes up with a new kind of death ray or drone weapon, most of it has been pretty much adjudicated.

Barsamian: Hunting is a tradition in the U.S., and a lot of people enjoy it, but why do they need military-grade weapons?

Nader: First of all, hunting is declining because so many young people don’t want to go out and hunt. They just want to send text messages about deer. Because they’re not interested in hunting, the deer are proliferating, and the ticks are proliferating, but we don’t want to introduce coyotes and bears. Did you know there are five hundred bears here in Litchfield County, Connecticut? They’re coming back. They love birdseed.

Why do people want military-grade weapons? Why do fifty-five-year-old men drive motorcycles without helmets? There’s a kind of power to it. It’s also a social activity. They have their clubs. They talk about guns, trade them, try to outdo one another. It’s their way of enjoying life. They’re having target practice. It’s pretty harmless.

When you go a little deeper, you’ll hear people talk about needing those weapons as a defense against tyranny. Some of these gun owners read American history. King George would have gotten a lot farther suppressing the American Revolution if those farmers in Massachusetts hadn’t had their rifles. Some gun owners see that autocracy can happen anywhere, and they want to be ready. They see other countries’ governments overturned, and their people stripped of their arms. They don’t want that to happen to them. As long as they’re law-abiding, I can sympathize with that.

When it comes to civic culture, we’ve been anesthetized into believing that we don’t count, that we can’t make a difference. We basically disenfranchise ourselves and revert to our private lives and try to make the best of it.

Barsamian: Do you see any connection between U.S. violence abroad and violence at home?

Nader: Of course. Look at all the traumatized soldiers who end up beating their spouses or committing suicide or sometimes killing people in mass shootings. These are seriously injured people. We call our soldiers heroes, but we insult their intelligence. The Pentagon allowed the professional pollsters at Zogby to poll soldiers in Iraq in January 2005. They found that more than 70 percent of the soldiers wanted the U.S. to get out of Iraq in six to twelve months. While members of Congress were beating the drums for more war, even a majority of Marines wanted our troops out of there. Do you know how much publicity that poll got? Almost none. It received about three column inches from the Associated Press. Why don’t we listen to the soldiers instead of just giving them medals? Why don’t we interview them? You don’t think they know what’s going on in Afghanistan? You think they believe Afghanistan is a winnable war? They’ll give you the details.

Barsamian: What if the war in Afghanistan were going well? Would that justify it?

Nader: Of course not. If it’s going well, it means they’re killing more people, disrupting more families, and destroying more infrastructure. If it’s not going well, it means it’s never going to end. This is the longest war in American history, and it was never declared by Congress. Heaven forbid that they should obey the Constitution!

That’s where the phrase “perpetual war” comes from — these U.S. attacks that have no strategy after the regime is toppled, like in Libya. There’s total chaos there to this day, and the violence has spread to other African countries. That was Hillary Clinton’s war as secretary of state. It was carried out against the recommendation of Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and the generals. So it’s still going on, year after year after year. Unwinnable wars are perpetual wars. And we should never go to war, winnable or not, against countries that don’t threaten us: Afghanistan didn’t really threaten us as a country; Iraq didn’t threaten us.

Barsamian: Why didn’t Obama go after the architects of the Iraq War: Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, and the rest?

Nader: Because he knew that as president he was going to violate other nations’ sovereignty, send drones over, send Special Forces. He was going to be caught blowing up wedding parties by mistake. He’s actually increased the drone attacks fivefold over Bush. So if he ordered the Justice Department to prosecute Bush and Cheney, the obvious next step would be to prosecute Obama.

The New York Times had a series of articles about “Terror Tuesdays.” That’s what the White House and the Pentagon call the weekly meeting President Obama has with his security advisors to decide whom to kill by long distance. Maybe they’ve spotted terrorism suspects going back and forth on a road in Yemen or Somalia. Sometimes there are civilians in the area. It’s up to the president to decide, in secret, whether to fire missiles from a drone. He’s prosecutor, judge, jury, and executioner. This is totally unconstitutional, and as a former constitutional-law teacher, Obama knows this.

We’ll never know if these particular people targeted by drone strikes are really imminent threats — which is usually the standard for the U.S. to launch a missile — or whether they are victims of grudges or completely misidentified. And are they even serious suspects, or just someone fingered by informants who want to get rid of them? What’s going to happen when other countries send drones over here to knock someone off? Are we going to tell them they’re violating international law? We’ve unleashed horrific risks, the penalties for which are being deferred onto our children.

We are letting rascals, charlatans, and warmongers hijack our government and violate our Constitution, sending U.S. soldiers to kill and die overseas, and these officials don’t get any jail time. That tells you who is controlling this country.

But it’s not that hard to turn the country around. Most people, whatever they call themselves — conservative, liberal, libertarian, progressive — have a deep sense of fair play and justice. They’re not sadists. They care for other people. We see this during a national disaster. All labels go out the window, and everybody helps rescue people from floods or fires. That’s what we want to tap into. That’s why I say fewer than 1 percent of the people, if they represent a majority opinion, can make a lot of changes. It won’t produce a utopia, but it will certainly produce a better country than we’ve been experiencing.

Barsamian: The year 2015 was the hottest on record, and this past July was the hottest month on record. Is the capitalist economic system as it presently stands, with its bailouts and tax breaks and loopholes and offshore shell companies, able to address climate change?

Nader: We’re sitting here shivering in the American Museum of Tort Law, so I have to adjust psychologically before I answer. I think the move toward solar energy, renewable energy, energy efficiency, wind power, and the rest is happening already, even though the fossil-fuel companies don’t want it to happen. I’ve seen a lot of false starts with the solar-energy industry over the years, but now I think its growth is irreversible. It’s a multi-billion-dollar industry. Solar panels are being installed on roofs all over the country.

Other countries are moving faster than we are. For example, Denmark and Germany are converting to renewable energy so quickly that within thirty or forty years they may be up to 80 or 90 percent renewable energy. Germany is closing its nuclear plants.

Energy expert S. David Freeman, who used to run the Tennessee Valley Authority and other public utilities, told me the other day that with a 3 percent-a-year conversion, our electric utilities could be completely converted to renewable energy within thirty years. So the question is no longer whether we’ll have renewable energy; it’s when it will happen.

Climate change is advancing rapidly. The temperatures are soaring faster than most climate scientists predicted, and the glaciers are melting. The flooding of Miami and parts of New York City and Boston is a very real possibility. So we’ve got to get busy. Congress must do more than just debate climate change. It’s time for action. We can end our dependence on fossil fuels. The engineers are ready; the scientists are ready; the workers are ready. Building infrastructure is the best kind of industry. You can’t export it to China, and it pays pretty well.

Barsamian: Climate change also has huge political implications around the world. The uprisings in Syria and Egypt were triggered by droughts and the resulting higher food prices. It’s been said that within several decades parts of the Middle East may become uninhabitable because of extreme temperatures. Already 125-degree days have become expected.

Nader: The drought in eastern Syria was devastating. They can’t remember any time in history when it was that bad. It pushed the farmers and peasants into the cities and was very destabilizing. That’s why the Pentagon considers climate change a national-security issue.

Barsamian: Sometimes I think of Pastor Martin Niemöller’s quote about the Nazis: “First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out. . . .” First the floodwaters came for the Maldive Islands, but I wasn’t a Maldivian, so I didn’t care. Then they came for Bangladesh, but I wasn’t a Bangladeshi, so I didn’t care. Then they came for Miami, New York, and Boston, and there was no one left.

Nader: Yes, and they saw the deniers Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity floating in the floodwaters. We’re seeing levels of ignorance that would shame medieval fanatics. [Laughter.]

Barsamian: It’s always good to laugh. It’s therapeutic.

Nader: In humor there is truth. Also, laughter has the same benefits as physical exercise in some respects.

Barsamian: We’re in the middle of another election season. You know something about running for office. You’ve challenged the two-party system — the Republocrats and Demopublicans, as you call them. What are the structural and legal obstacles to creating a viable third party?

Nader: Let’s say you’re a Green Party candidate, and you want to get on the ballot in fifty states. In some states, like New Jersey, it’s fairly easy. In others the laws are draconian. In California it’s 177,000 verified signatures, and you have only a few months to do it, and really you’ve got to get twice that many, because some names will be illegible or people will play pranks and sign phony names.

If you do get on the ballot and have enough support to get 3 or 4 percent of the vote, you’re viewed as a spoiler by the party that you’re closest to, and they will hurl all kinds of litigation against you in state after state. You won’t have money to hire lawyers, and your resources will be depleted. The press, too, will call you a spoiler and say you can’t win, so why are you trying? My campaign had twenty-three lawsuits brought against it in twelve weeks in the summer of 2004. It was an impossible burden. We ended up having only seven weeks to campaign after Labor Day.

The U.S. is the only country in the Western world that places so many obstacles to getting on the ballot if you’re not a member of an establishment party. That’s one reason why Jimmy Carter has said we are not a functioning democracy. He said when he is asked to monitor elections in other countries, he has five criteria for a functioning democracy, one of them being a multiparty system. He said the U.S. has met none of those five criteria.

Barsamian: What’s your assessment of the Bernie Sanders campaign: how it was organized, his appeal, his choice to run as a Democrat rather than as a third-party candidate?

Nader: I think Sanders was smart to run as a Democrat, because he saw what happens to people who run in third parties, and he didn’t want to be marginalized, kept off the debates, asked every day, “How do you feel about being a spoiler?” instead of being asked about his policy proposals, such as full Medicare for everybody, tuition-free higher education, and a tax on Wall Street speculation. And he got a lot farther than anybody dreamed, including him.

He also did something priceless: he raised $225 million in contributions that averaged twenty-seven dollars apiece. You know how many times the Democrats have said, “We are for campaign-finance reform, but we’re not going to unilaterally disarm when we’re up against the Republicans and all their fat-cat donors”? Well, Sanders did it: no super PACs, no fundraising events in Beverly Hills and on Park Avenue. He has demolished the Democratic Party’s excuse in the future.

Barsamian: What does he do now?

Nader: I think he should lead a nonpartisan civic movement all over the country: hold a million-person rally on the Mall in Washington, D.C., and then break it down regionally, pushing for political revolution. If he runs it in a nonpartisan way, he will avoid discouraging his followers, who will split apart if he doesn’t pull them together right away. He will lose this amazing constituency he has.

The movement needs to be a coalition of Left and Right. That’s what scares the politicians. When conservatives and liberals walk in together, senators turn pale.

Barsamian: Sanders calls himself a “democratic socialist,” but wouldn’t it be more appropriate to describe him as a New Deal Democrat?

Nader: Yes, he would have been very much at home among the progressives in Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s tenure. Sanders doesn’t promote socialism by the textbook definition, which is government ownership of the means of production. He’s like the democratic socialists who have won elections in Scandinavian countries and from time to time in Germany, France, England, and elsewhere. In this country we have a mixture: we have some democratic socialism, like Social Security, Medicare, public schools, and public parks; and we also have corporate socialism, like the military-industrial complex and corporate welfare. The corporate socialism is devouring more of the budget than democratic socialism. You don’t see a movement in this country to cut massively bloated military spending, but you do see a movement to cut Social Security and restrict Medicaid.

Barsamian: What did you make of the discrepancy found between the outcome of some Democratic primaries and the exit polls?

Nader: I think there are shenanigans that go on all the time when the primaries are close — within, say, 3 percent. If you control the machinery — and I think Hillary’s people controlled the machinery in Iowa and Nevada — you can tip it. There are all kinds of clever ways. If it’s 5 percent or more, it’s difficult. I should say, though, that there’s a question as to whether exit polls are as accurate as they were thought to be years ago.

Barsamian: And what about the privatization of voting technology?

Nader: That’s another way to steal elections. The voting machines’ software is owned by a corporation that sells it to the states. It is remotely controlled and can be hacked. Why do we have electronic voting machines at all? We should have printed ballots in every state. The vast country of Canada has printed ballots, and by 11 PM on Election Day they know who has won. If there’s any question, the ballots are there to recount. Some U.S. voting machines print results, but others don’t. A lot of them are breaking down or antiquated. New ones cost hundreds of millions of dollars. And whenever municipalities or states buy new machines, there’s almost always some form of noncompetitive bidding, and palms are greased. I say get rid of the voting machines, go back to printed ballots, and raise a champagne glass to our friends in Canada who taught us how to do it.

Barsamian: What about the idea of universal voter registration, like France, Mexico, and other countries have?

Nader: Why should we have any registration? When you reach the age of eighteen, you vote. Let’s make voting a civic duty, like jury duty. In Australia if you don’t vote and you don’t have an excuse, you can be fined twenty bucks. The money goes into the electoral fund. That’s why Australia has over a 90 percent turnout in federal elections. We’re lucky if we get 60 percent.

I could see someone saying, “I don’t want to vote for any of these candidates.” So let’s include the option to vote against all the candidates. Every ballot would have a binding “None of the Above” line. If “None of the above” wins, we have a new election, with new candidates. Voting “None of the above” would make more of a statement than staying home. It would become a political force, a watchdog. Can you imagine politicians losing to “None of the above”?

Changing things is easier than we think. We just have to get off our chairs and show up: to elections, courtrooms, town meetings, marches, rallies. Showing up is half of democracy.

Barsamian: What are your thoughts about the Green Party presidential candidate, Jill Stein, and Gary Johnson of the Libertarians?

Nader: Obviously I look more favorably on the Green Party agenda. I think Johnson is pretty good on military policy and civil liberties, but he’s against health-and-safety regulations, Social Security, and Medicare.

The problem with the Green Party is that they don’t run enough local and state candidates. That’s the way to nourish a national candidacy. The Green Party also doesn’t know how — or doesn’t want — to raise money. You’ve got to raise money if you’re going to run.

But my greatest criticism of the Green Party is its lack of energy. I used to say that getting the Greens collectively to do something is like pushing a string.

Barsamian: What are voters to do when they are given just two choices and don’t like either one?

Nader: It depends on your personality and character. For my part, I always vote my conscience. Trump is a horrible candidate — he’s unstable, bigoted, and ignorant — but I also believe that Clinton has had more experience in getting us into wars and supporting Wall Street bailouts. I don’t want to be complicit when, once she is in office, she slaughters innocents abroad and caters to big banks. So I believe in a vote of conscience. But if you choose to be practical in the few swing states and vote for Clinton to avoid a Trump presidency, then you have a moral obligation to ride herd on her administration, because otherwise you will be complicit. You’ll have legitimized them and the illegal and violent and greedy things they’re going to do. If you want to make a tactical vote, then you’ve got to make sure that politicians are not committing crimes in your name.

Barsamian: Does the prospect of Bill Clinton as “First Gentleman” concern you?

Nader: Very much, because he’s an incorrigible corporatist. Thomas Frank, in his brilliant new book, Listen, Liberal, takes the Clintons apart calmly and precisely from a left-wing perspective. You can’t reform the Clintons. They will give you all the rhetoric and the slogans; they will tug at your heartstrings in African American churches; and then they will betray everybody with trade agreements that promote globalization, with crime bills that put more nonviolent people in prison, and with the 1996 Telecommunications Act, which allowed media consolidation. The Clintons’ record is replete with promises they fed to gullible voters and then broke.

Michelle Alexander, an African American law professor, wrote an article in The Nation earlier this year on why African Americans should vote against Hillary Clinton. One of them was the so-called welfare-reform act of 1996, which turned out to be very bad for African American single mothers, and the other was the 1994 crime bill, which worsened mass incarceration with a three-strikes provision. But the African American vote still gave Hillary Clinton a tremendous lift in the early primaries.

Barsamian: Some of your critics accuse you of being a tinkerer, always making slight improvements in the system rather than overhauling it. They say you’re basically renegotiating the terms of our enslavement. How do you respond to that?

Nader: I’ve always had both a micro outlook and a macro outlook. If you want to mobilize people to create a society worthy of our ideals and principles, you start by winning battles against things that everyone agrees are bad: dirty meat and poultry, unsafe cars, hazardous drugs, toxic air, contaminated water, consumer fraud, worker abuse. Once people see how they’ve been disrespected, excluded, and denied a voice, they begin to consider changes to the bigger picture instead of band-aids and temporary fixes. But we’d better start doing that soon, because the corporate hordes have the money to buy everything, including elections.

To fight back, you need about a million people who are concerned enough about the future of our country and our world to make civic action their principal hobby — and who will spend three to five hundred hours a year on it and fund some full-time advocates. If we had a million people whose hobby was controlling Congress, it would happen. Some of these battles we’ve won in Washington, there haven’t been even a thousand people fighting them. Once your aim becomes massive transformation, however, the corporate structure will strike back, and you’ll need about a million people representing the majority opinion.

When that happens, the media will start reporting on it. The media like winners, and they like numbers. If they see four hundred thousand people protesting outside the Capitol, they’ll report it, because it would be too visibly embarrassing for them not to.

The movement needs to be a coalition of Left and Right. That’s what scares the politicians. When conservatives and liberals walk in together, senators turn pale. If a liberal comes in, they still have the conservatives. If a conservative comes in, they still have the liberals. They know how to divide and conquer, but that strategy won’t work against a Left-Right coalition, which is why I wrote my book Unstoppable: The Emerging Left-Right Alliance to Dismantle the Corporate State.

Barsamian: In an interview you gave some time ago, you said, “You’ve got to keep the opposition off balance. Once you get them stumbling, you can’t let up. That’s the only way to get results.”

Nader: Right. Once you’re on the defensive, once you’re reeling backward, you can’t push back. You’re just trying to keep from sliding farther. And our side has been on the defensive for three decades or more. People tend to focus on keeping things from getting worse rather than on making them better. I ask citizens’ groups, “Do you have a department that’s on the offense, rather than just trying to stop the other side from rolling back your past achievements?”

Barsamian: I give public talks around the country, and often the first question people ask me, no matter what the topic, is: What can I do?

Nader: One thing I tell people to do is to find out what resources in their communities they don’t use, including the ballot box. And don’t be afraid of raising money. Listen, the abolition movement ran on money donated by wealthy Bostonians. Rich Philadelphia matrons funded women’s suffrage. There’s this idea that if you’re fighting for justice, money isn’t important. But it is necessary when it comes to having more organizers and more allies and more facilities and more media and more resources and more technology. We have hundreds of billionaires in this country. Some of them are fairly enlightened. Some of them got together with Chuck Collins, who directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good, to stop the Republican repeal of the estate tax. Those billionaires, including Warren Buffet and Bill Gates Sr., father of Microsoft’s Bill Gates, basically said, “Nobody does it by themselves.” The money needs to be there to hire the organizers and to pay for all the activities that are necessary.

Barsamian: What would you say to a young barista working in Boulder, Colorado, who’s interested in public service? How might she go about that?

Nader: That’s easy. There are national, regional, and local environmental groups, consumer groups, women’s-rights groups — everything. You can join any group instantly online. I would advise her to start locally, because that’s where you get the experience — all the joys and sorrows and difficulties and challenges that bring out the best in you.

Barsamian: You turned eighty-two in February. I know it’s too early to talk about your retirement, but could you talk about your legacy?

Nader: Whatever we have put in place is probably going to stay in place. Are they going to rip seat belts out of cars? The best legacy is to get as many people in the next generation to stand on the shoulders of the previous generation and outdo them. People my age must always operate on the belief that the best is yet to come.

For a more recent interview of Ralph Nader by David Barsamian — “The Great Work: Ralph Nader on Taking Back Power from the Corporate State” [May 2019] — click here.