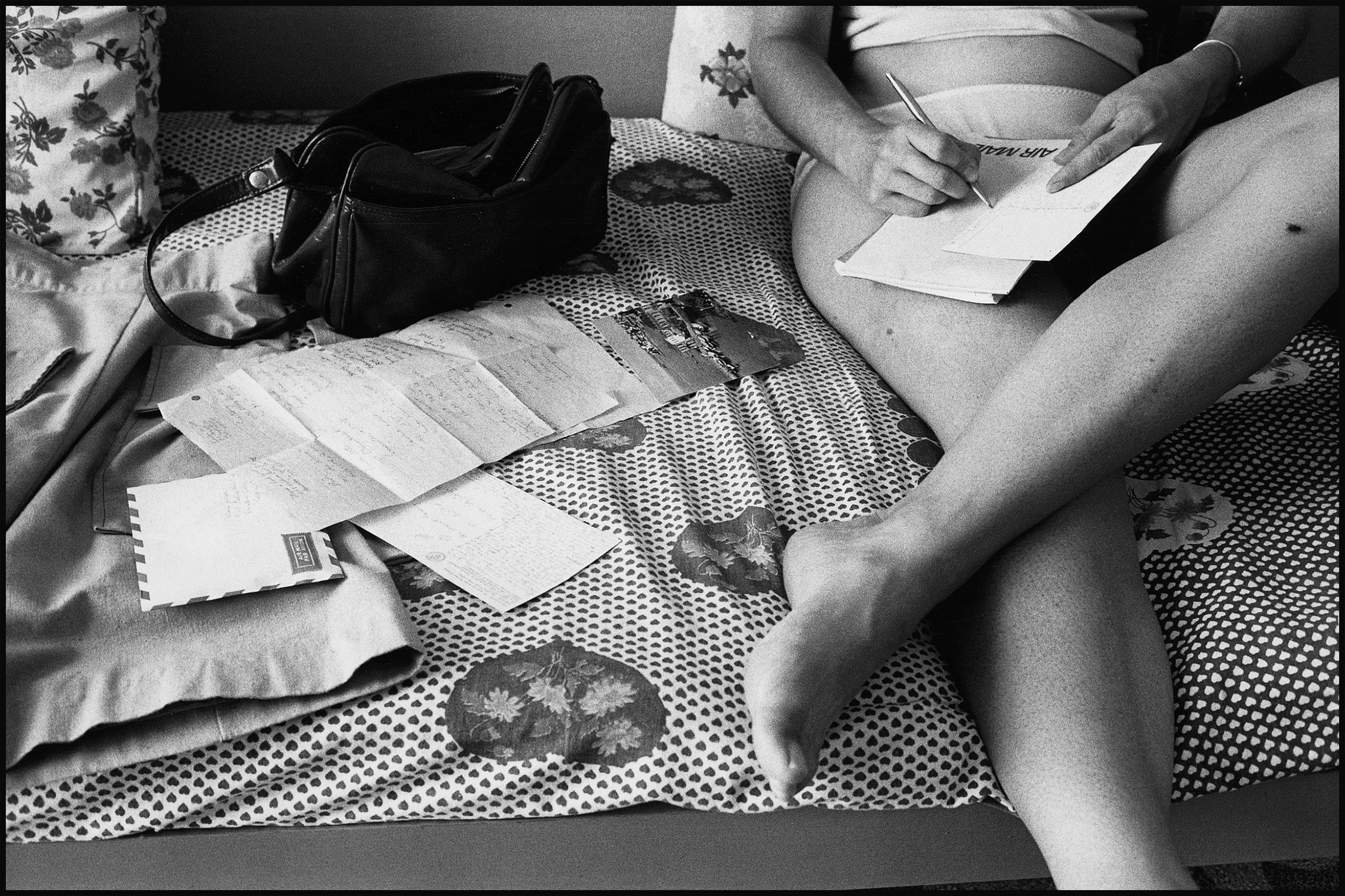

The shop was open from 10 A.M. to noon and again from 2 to 4 P.M., because in Austria everyone needs a good, unhurried lunch, and anything you can’t do today you can do tomorrow. I slipped into the narrow, dim space and inhaled the smells of loose tobacco, milk chocolate, and stacks of thick paper. Passing the roundish proprietor in his hunter green boiled-wool cardigan, I stopped at the wall of pens: thirty-seven shades and ten different tips. They all made urgent, dramatic marks on the tissue-thin pink airmail paper. After much deliberation, I chose the midnight blue fine-point, handed over the crumpled two-hundred-schilling note I’d received for selling my plasma earlier that day, and took the change to a cafe, where I could sip my coffee for hours as I wrote letters home.

This was before e-mail, and my only choice was between the expensive instant gratification of a phone call and the languorous pace of a letter that would be hopelessly out of date by the time it was read. Letter writing was a dreamy and timeless activity, like walking somewhere when it would have been faster to drive. Sometimes I would drop little pieces of my life into the envelope: a bus ticket, a bar coaster, a page of a newspaper, or a leaf from Hellbruenner Allee, where I walked every day.

While in Austria I received my first and only Dear John letter. Considering how long it took overseas mail to arrive, he’d probably already forgotten me by the time I opened the envelope. He’d had a change of heart, he said, and hoped I wouldn’t be mad. This he scrawled with a cheap ballpoint pen on a scrap of notebook paper. The letter was so small he didn’t even need to fold it.

Toni Ouradnik

Mountain View, California

My husband and I live with my father in a big, rambling farmhouse. My brother and his family have settled here, too, and three generations of us jostle about the drafty rooms. We listen to baseball games on the radio, watch the children dance to marching songs on the Victrola, and mow acres of lawn.

In spare moments we listen to my father tell of his upbringing as the child of Salvation Army officers, of his travels through Europe and North Africa on a motor scooter, and of the years he spent in Spain working on a novel. Being a practical man, he teaches us how to repair the dripping faucet, patch a leaky pipe, and refinish the dining-room floor.

As my father becomes less mobile, he retreats to the living room, where he sits in his chair watching television, or to the kitchen, where we take turns cooking meals and sharing gossip. People hint to me that our situation is odd, that I should have moved out of my father’s house when I got married. But it works for us.

One night in February, my father slowly walks to his bedroom with his cane, calling out, “See you tomorrow.” The next morning I find him lying beside his bed, dead.

For weeks I walk through the house, touching his things: a cuff link, an ashtray, an old suitcase with a Greek Line shipping label. In the second week after his death, I find the letters: just a handful, seven or eight, written years ago to my grandparents on his old Underwood typewriter. When I try to flatten them out, the brittle paper begins to tear and crumble. I handle them gently, reverently. My father’s words come back:

Here he is living in Spain with my mother. The car is broken down, and he’s trying to have it fixed. They are visiting Portugal and arranging to come back to the U.S. in the fall, on the SS Anna Maria. “Don’t be sad,” he tells my grandmother when her mother dies. His daughter (me) is learning to speak and sing “Heigh-ho” and “all that jazz children do.” Right now she is going to bed. “And she’s objecting! One should always object,” he writes, on that distant spring evening in Madrid.

I read the letters every night for the rest of the winter and on into spring, after my miscarriage. They comfort me. On the typewritten pages we are all young again and full of possibility.

But they don’t bring him back.

Renee E. Fox

Canterbury, New Hampshire

In the summer of 1971 I received a postcard from Greece signed simply “Mark.” It was addressed care of the couple I was staying with just outside of Vancouver. I would be at their house only until the end of August, at which point I planned to leave Canada and hitchhike around Europe.

On the front of the postcard was a mosaic with a sun in the middle. On the back, written in blue felt pen using all lowercase letters, was this message:

heather —

i live in an olive grove, dense and green, among broad bands of ferns fired to golden hues by thick yellow bolts of greek sun penetrating the olive canopy: in an isolated valley among scattered farmhouses, grape vineyards and wheat fields. and you? hope you are well and active, alive — love, mark

The thing is, I have no idea who Mark is. Few people even knew where I was staying that summer, let alone had the address. How could this Mark not only have known, but thought to carry the address with him on his travels?

I have kept this postcard for more than thirty years. Every so often I get it out and look at it, hoping this will be the moment when my brain will make a connection and offer up a memory. But it never has. The postcard remains, like life, maddeningly and wonderfully mysterious.

Heather MacAndrew

Victoria, B.C.

Canada

Not long before he died in Berlin, Germany, my father sent me the letters I had written to him between the ages of seven and ten. They date from 1947 to 1950, a period when Mother and I were struggling to survive in the Soviet occupation zone.

These Dear Vati letters were addressed to a man who had been imprisoned for child molesting when I was a year old, and who was obliged upon his release to serve on the German home front during the war, cleaning up after air raids; a father who had salvaged a teddy bear from a smoldering ruin and sent it to his daughter. (It would be my only childhood toy.)

These Dear Vati letters came from a child who often heard her mother speak of her father as “the pig”; a child who vaguely knew that her father had done something that had to do with little girls, something despicable.

My mother and I had left Berlin in 1944 after our apartment was destroyed in an air raid. My father had stayed and ended up in the American occupation zone after the war, where he found employment as a truck driver. He had access to food and essentials, like shoes, nails, and light bulbs. We lived in a town of six thousand at the Czech border and had nothing. In my letters I begged him to send us food. I disliked, distrusted, even despised this man, and yet he was my father.

Meticulous drawings illustrate the letters: a stocking with holes, our temporary house, our vegetable beds, the overflowing Elbe River. I remark on the trivia of life: the weather, a neighbor, illness. I request flour and sugar for a birthday cake. One letter reports that a food package arrived empty, its contents stolen. A picture of a crying face accompanies the line. Another letter says, “Mutti was desperate because we had nothing to eat in the house.”

I remember what my mother said to me one night when I woke up hungry: “We don’t have any food in the house, but if only I could, I’d carve it out of my flesh.” I never again mentioned hunger. I never cried or complained. I didn’t want to increase her burden.

At the age of seven, I write jubilantly, “We’ve got an outhouse now!” Before that we had only a bucket, the contents of which we poured into holes we’d dug in the garden. I tell my father of mending stockings by candlelight, because there is often no electricity. I report receiving four nuts, eight rolls, and an egg for my birthday, and Mother a basket filled with wood. I write that we filch wood from the forest when we have nothing left to burn. Once, we were almost caught but got away by jumping on our sled, on top of the logs we had stuffed into potato bags. Another time we were caught, and Mutti cried, begged the man not to denounce her, and bribed him with a damask tablecloth we had.

When I was nine, Mutti’s finger became infected to the bone. For weeks she was unable to sew for income or do any work at home. I wrote proudly that I was doing all the household and garden chores, including sawing logs and splitting wood. And when the Elbe River flooded, I had to balance on boards propped on high sawhorses to get to school.

More drawings: of the mountain I saw from my window; of the Christmas tree we cut down and decorated with candles and homemade ornaments; of the garden and the vegetables and flowers in it.

These letters are my father’s greatest gift to me. I cry whenever I read them. I have not stopped crying yet.

Name Withheld

My high-school English teacher, Nancy Thompson Harris, told me that if I kept working at it, I could be a “splendid” writer. She said she was saving all my letters for when I became famous. She and I wrote each other from the day after my high-school graduation to the week before she died: almost twenty years. Her teacherly cursive filled the front and back of many yellow legal pages. She called me “dear heart,” recommended books and movies, and filled me in on the politics of the English department.

Nancy always wrote me back immediately upon receiving my letters. When I was away at college, it was thrilling to have such a responsive audience for my latest wise and mature insights. Years later, however, when I had three young children, I would sometimes wait to write back, to give myself some breathing room.

Even after Nancy got cancer, her letters remained upbeat. She described chemo and radiation. She sent photos of herself in various hairdos that made the most of very little hair. She wrote about using marijuana for the pain and about her plans to move in with her sister. By then I was writing back the moment I received her letters, and it was her responses that had slowed down considerably.

One summer day I got a letter from Nancy’s sister. Nancy was gone. I remember wailing. My husband took our three children out of the house that afternoon so I could be alone.

If Nancy did save all my letters, they are gone now. I am not going to be famous, so it’s no great loss. I do wish I had them, though, to help me re-create the twenty years during which I became an adult, a wife, a mother, and a friend to one of the liveliest women I have ever met. Knowing my letters were being saved pushed me to be disciplined about my writing: to take care with every sentence, to dig deep, to make it “splendid.” I think that might be what she intended all along.

Anjelina Citron

Bellingham, Washington

My friend passed me the letter under our desks in seventh-grade math class. She was popular and pretty, and I was short and stocky with white cat’s-eye glasses. We’d become friends only because we lived in the same neighborhood and did homework together after school.

The letter was signed “A Secret Admirer,” but my friend assured me it was from the boy I had a crush on. The silver band inside was a perfect fit, and I wore it proudly on my left ring finger. I was to meet him after school on Friday, outside the band room, the letter said.

That week I became the center of attention among my friends, who questioned me excitedly about my date. I sewed a new dress and dreamed of my first kiss.

On Friday he was standing by the band room, just the way I’d imagined. But when he saw me, he asked me what I was doing there. He wasn’t waiting for me. My friends had told him to wait there for another girl, the one he really liked. They had used him to humiliate me. How stupid I had been to believe that someone would actually like me.

If the girls had staged the prank to make me stop hanging around with them, it worked. I stayed home alone all that summer. When school started again, however, they all asked for help with homework, and I was so in need of friendship that I agreed. No one ever mentioned the letter.

In college I must have fucked about a hundred guys, and a few women too, I was so desperate for love. I married a man who doesn’t really love me, and I have let him abuse me for the last sixteen years because I just don’t believe I am worth loving. I am still a fool, because I want the same thrill I felt while waiting for that Friday to come.

The girl who passed me that letter called me yesterday. We haven’t talked for years, although we continue to live in the same small town. She was calling to try to sign me up for some pyramid scheme — a “sales opportunity,” she called it. I declined politely.

The worst part was that she was still trying to trick me.

Name Withheld

I am my neighbor’s secretary. Mrs. Scott has dictated to me letters to her family, her friends, her enemies, the IRS, and Publishers Clearing House. I have typed up her will. I have sent angry letters to her ex-boyfriend, signed with a fake name. The art of letter writing is alive and well with Mrs. Scott.

Whenever Mrs. Scott needs administrative support, she comes barging through our back door, wooden cane in her fist, looking ready for a fight.

“Suzy Parker, I need something written,” she says. Our dog barks. Our bird screeches. Everything comes to a halt.

“What you got to eat around here?” she asks, peering with disdain into the refrigerator. I fix her a cup of coffee the way she likes it, with milk and a heaping tablespoon of sugar. I toast soft white bread, smear it thickly with butter and jam, and place it in front of her at the kitchen table. When she is finished eating, she is ready to get down to business.

I sit at my computer. Mrs. Scott perches behind me on a wooden chair, squinting over my shoulder at the screen, and dictates:

Dear Publishers Clearing House,

If I have won the sweepstakes, please deduct the $12.51 + $2.50 from my millions and send me a check for the balance of what you say I have won. It’s true, I do have a winning smile and therefore deserve to win. Do not send me ANYTHING but money. I thank you for the great opportunity, and if this is not true please don’t send me any more of your messy mail.

Hope you are wonderful,

Mrs. Gerstine Scott

Dear Mrs. Adams,

Hello, dear. It’s been a long time since I heard from you. I always wondered what happened to our forty-year friendship. You and I never really had time to talk things over. You always want things to go your way, but I know more than you think I do. Maybe someday you will see what I was telling you all along. When you were sick, I was always there, but when things happened to me, you were never there.

God bless, from yours,

very sincerely,

Sister Gerstine Scott

Last Will and Testament

To Whom It May Concern,I am Gerstine Scott. In my apartment everything except the cookstove and the curtain in the front room belongs to me. My son’s name is Robert Douglas. He is the one to have everything in this apartment if something should happen to me. As of this day, November 1, 1998, I don’t owe money to anybody. This is decorated in order by Gerstine Scott in the City of Oakland and the County of Alameda.

P.S. Mrs. Jones is the owner of the property, and she gets the cookstove and the curtain. Leave Suzy Parker my cane. She bought it for me when I lost my old one, and I greatly appreciated that. Someday she is going to need my cane, though she don’t believe it now.

Susan Parker

Oakland, California

I met David on the train back from Michigan State University, where we both planned to enter college in the fall. I was eager to discover the world beyond my boring Jersey suburb, and David was unlike any of the boys at my high school. He spoke of literature and ideas, and he read me one of his poems. I’d never met anyone who wrote poetry, except for a class assignment.

As the train trundled across the winter landscape, we kissed in our seats, only dimly aware of people walking by. By the time we reached New York, I was in love: with David, with poetry, with life. He got off upstate, leaving me a poem, and I continued on to New York City, where I took the bus back to New Jersey, reading and rereading his poem the whole way.

David and I wrote fat letters back and forth all spring. My heart leapt whenever I found a bulging envelope from him on the kitchen table. I’d race upstairs to read it in the privacy of my room, tears welling at the poignancy of our long-distance love. David wrote poem after poem, all inspired by me, he said. Could I really be as special as he thought I was? I wanted to be. I wrote my first poem. David told me I had a natural talent. I wrote more.

I said not a word to my girlfriends about David. I even continued to double-date on the weekends with my best friend, Libby, though my mind was on David and his letters.

One day Libby walked home from school with me. I hoped there wouldn’t be a letter that day, but I saw one through the screen door, sitting in plain sight on the table. I rushed to scoop it up.

“What’s that?” Libby asked, snatching it from my hand. “Oh, very interesting: a letter from a boy!” She waved the envelope in my face. “How could you hold out on me like this?”

I tried to appear casual, but she saw through it. Upstairs in my room she taunted me, holding the letter out of my reach. Then she tore it open and began to read out loud. The romantic words that I’d cherished in secret sounded impossibly silly on her lips. She singsonged her way through David’s latest love poem.

“He says he’s coming to the city, and that you’ll meet him there. You’re not going to see this guy, are you?” she asked in disgust. “He’s weird. Maybe dangerous.”

“No, I don’t think I will,” I said, though I’d been eagerly awaiting this New York weekend since David and I had said goodbye on the train. “He’s just a friend,” I assured her.

After Libby left, I reread David’s letter. I felt none of the old excitement. His next letter came, full of anticipation at seeing me in just two days. I could hardly bear to read it.

I evaded David’s calls all weekend, thinking I could write him a letter of apology the next week and make everything right again.

In the middle of Sunday dinner, the phone rang. My mother picked it up in the kitchen. “Just a minute. She’s right here.”

“Tell him I’m not home,” I said. But my mother, who’d been taking messages from David all weekend, would have nothing to do with my subterfuge. When I flatly refused to take the call, she returned to the phone and told David I didn’t want to talk to him.

The thin letter that arrived that week was hurt and angry. I don’t remember whether I responded. There was nothing I could say.

Joan Leslie Taylor

Santa Rosa, California

I had been working all day when I returned to my cell and found a letter on my bunk. It was from a woman whose name I didn’t recognize. I opened it and read.

I’m an ex-gang member in prison for killing someone from a rival gang. This woman said she’d been praying for me and told me how her son had been killed by boys who were influenced by gangs and drugs. I guessed that a priest or nun had given her my address in hopes that we could help each other.

“If you don’t know who I am by now,” she wrote, “I am Jerry’s mom.” I looked back at the name at the top of the letter, then put the letter down and stepped away from it.

“What’s up?” my cellie asked.

What could I say? “It’s from the mother of the dude I killed.”

She said in her letter that she wasn’t writing to judge or condemn me; that if Jesus Christ’s mother could forgive the soldiers who crucified him, then she could forgive me. And if the Virgin Mary could accept those soldiers as her own children, then she could accept me as “her own.”

Her other son was drawn to gangs and on heroin, she said, and she asked if I could write him a letter and pray for him. I was overwhelmed. I did as she requested.

All prisoners treasure their correspondence. I know one who has saved letters from his loved ones for nearly thirty years. I send mine home. Boxes of them sit in my mother’s garage. Those letters are sacred to me.

This, however, was a letter I was going to put in my photo album, where I keep the things I love and treasure most. But before I did that, I wanted to share it with a friend who was a Franciscan nun. I sent it to her as an example of the healing power of Christ’s love. I asked her to return it when she’d read it.

After a few weeks, I asked my friend why she hadn’t returned the letter. Unfortunately, she said, she had thrown it out.

Raphael Cabrera

Calipatria, California

In 1976 my British husband, our two young children, and I moved from Tennessee to rural England. I left in high spirits. Little did I know how homesick and lonely I would be.

Our boys went to primary school in the village all day, and my husband left for work before sunrise and didn’t return until 7 P.M. He had the car. Having no extra money for bus fare, I was stuck at home. Strangers like us were eyed with deep suspicion in that tiny hamlet. I had to call the police twice to stop our boys from being beaten up by older children.

We had moved to a house built in the 1690s, and it needed a great deal of repair to make it habitable. Previous owners had put in doors and cabinets of particle board, covered cracks with masking tape, and placed dry-cleaner bags over the brick floors to keep out the damp.

With wages low and inflation at 26 percent, our limited savings were soon gone. There were no bargains. (One pair of poor-quality socks cost as much as six pairs in the U.S.) We struggled to look after my husband’s mother, who suffered from “emotional exhaustion.” For years we checked her in and out of a rest home. We’d clear out her fridge, notify the milkman and postman, and turn off the gas and water, only to reverse the process within a few days — or even hours — when she changed her mind.

I cried every day for two years. Sometimes my husband would find me hiding beneath the bed and ask, “Are you OK?” Some things still make me cry: the call of a jaybird on the soundtrack of an American movie; hearing Southerners speak.

During those years, I wrote many letters to my mother about the beauty of the English countryside, the changing weather, the historic towns and cities, the boys’ achievements at school and in sports, the new kitten. I described the strange money, the many odd names for bread (bloomer, cottage, tall tin), and the colloquial phrases of rural Sussex. How could I have told her the truth? It would have broken her heart. Even now, there are things I won’t tell her.

A few years ago, my mother came to visit and brought three shoe boxes containing every letter I had written her, still in their envelopes, numbered and tied in yearly bundles. I don’t know why I am keeping them. I am afraid to read them, to relive the sorrow hidden between the lines, the passing of a life I didn’t expect to live.

Mary Murphy

Hailsham, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Helen was ninety-six and had Alzheimer’s. She was living in a northern-California nursing home where I volunteered. There wasn’t much Helen could do, but I noticed that she liked writing letters, so I told her about my Aunt Phyllis, who was looking for a pen pal.

There was no Aunt Phyllis. She was a product of my imagination, and I spent many happy hours pretending to be her as I wrote letters to Helen. I delivered the letters myself, because Helen could read a letter if you put it in her hand, but a closed envelope was a mystery to her.

Each time I gave Helen a letter, I had to explain who Phyllis was. The scheme occasionally seemed futile, but I enjoyed donning the garb of one frail elder writing to another, and Helen delighted in the letters. I always left her with a stamped envelope addressed to Phyllis.

“I am so pleased that you wrote to me,” Helen responded. “It is great, at my age, to have a new friend.” Once, in reply to a story from Phyllis, she wrote, “I also had a playmate who enjoyed dolls. Each morning we would decide which dolls we would play with. . . . She had fancier things than mine, but my mother, although busy, managed to keep my dolls so nicely dressed that I was quite happy with what I had. So, you see, although I am very old, I have happy things to think about.” Another time she wrote, “I lost my husband and am not accustomed to being confined to one room, and while I can go out into other parts of the house, it isn’t mine.”

After about six months Helen declined to the point that she could not write letters even when I was there to prompt her. She would write a word or two and then simply forget what the pen was for. Sadly I bid goodbye to Phyllis and filed the letters away.

Lauri Rose

Bridgeville, California

As I was leaving the mall one day, I noticed a melancholy old vendor selling used books outside the B. Dalton. He wasn’t offering bestsellers (not from this century, anyway), and shoppers flowed around him like a river around a fallen tree.

I’m a sucker for old books, with their embossing and hard covers and antiquated fonts. They often have inscriptions on the endpapers and never have a UPC label printed on the jacket.

I asked the bookseller if he had anything that might be of interest to a writer. He reached for a book as though he had been waiting for someone to make just such a request.

The book was Frost’s Original Letter Writer, published in 1867. The table of contents was a list of common missives: “To a Friend on the Loss of a Limb by Accident”; “Letter Answering an Advertisement for a Chambermaid”; and, my personal favorite, “Letter Congratulating a Friend on Arriving at Maturity.” I gladly paid eight dollars for the book and hurried home.

That evening I read snippets of the letters to my husband. We smiled at the shy propriety of the suitors, and grew thoughtful at the condolence messages to parents who had lost children. The only letter I decided not to read aloud was titled “Letter from a Repentant Son to a Father.” It read, in part:

Dear Sir,

I dare not call you Father until you tell me that my deep and sincere repentance has removed the just anger that you expressed. . . . You told me that I would live to see the sinful folly of my course and deeply repent the sorrow I was causing both to yourself and my mother. . . . Oh, I have felt the bitter truth of your words in my inmost heart, and I can never again know peace until you will assure me of your forgiveness for the pain I have caused you. . . .

Your erring but repentant son.

I thought of the letter from my husband’s son that lay on our dining-room table. The white envelope bore a smeary red stamp: THIS CORRESPONDENCE IS FROM AN INMATE OF THE ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS. The letter inside read:

Dear Dad,

I just went to court yesterday and pled guilty. I’ll end up doing a few years. . . . I decided to finally read the self-help book you sent me, and I’ll let you know what I think about it when I’m through. I’ve never read a self-help book because I used to be under the impression that they were for pussies. I used to have to prove what a tough bastard I was. I’ve mellowed out quite a bit in the past year or two. . . . I haven’t heard from my son in a couple of months. I faithfully write him once a week, but I don’t get a response very often. Please have someone mail me a money order ASAP or visit me on Sunday between 1 and 5 P.M. and bring a money order. Please, Dad. I already owe some cigs, and if I don’t make commissary this Tuesday I’ll be in trouble.

Love, B.J.

J.K.

Fairview Heights, Illinois

He and I became friends in our sophomore year of college, and we spent many nights talking until the sun came up. For my junior year I transferred to a different school. My first semester at my new college was difficult, but his letters made it bearable. I relished them the way I did the first smoke of the day. Sometimes I’d read his words and wonder if there might be more than just friendship between us.

Then he graduated and moved back to California. I was still in school. I didn’t hear from him for months. When he began writing again, he had a girlfriend; they were living together. Oh well, at least we could still be pen pals. He wrote of his adventures as a ski bum, and I wrote about how much I wanted to be done with school. Somehow we were able to convey that we missed each other, thought of each other, and maybe even loved each other, without coming right out and saying so.

The summer after I graduated, he wrote that he was attracted to me, even though he hadn’t seen me in more than a year. He asked if I thought it was possible to love more than one person at a time. I called him immediately. We talked for hours but came to no conclusion. I did, however, say, “I love you.”

For many years we loved one another in every way except physically. We saw each other but once a year, if that. We continued to write. I had never before experienced such intimacy. I exposed my true self to him in my letters.

He had girlfriends; I had boyfriends. There were moves, job changes, periods when we didn’t write, times when we felt frustration at not being able to see one another. In every letter, questions seemed to linger: What if we lived closer? What if we were a couple? What if we had sex?

I needed to find out the answers to these questions. I needed to stop writing and act. I told him I was coming to visit him for a week. He said he couldn’t wait.

We talked for days. We spoke our hearts. We had sex. Our friendship didn’t come to an end. I had never felt so comfortable, so close to anyone. He told me he had never before made love to someone as an equal.

That was a year ago. He’s still in California, and I’m still in Idaho. Neither of us is interested in a long-distance relationship. We are two people who love each other and share a life together through letters.

Gina Bonaminio

McCall, Idaho

They arrived in plain white envelopes and were written on yellow legal paper. They followed me from Texas to Virginia to Washington, D.C. Occasionally there were dollar bills tucked into the folded pages, or newspaper clippings announcing weddings or births.

Mom’s familiar handwriting told of the weather, what crops Dad was planting, how many loads of laundry she’d washed that day. As a young woman eager to escape the family farm, I wanted correspondence filled with existential questions, socioeconomic history, or revealing human drama. What I got were the letters of an ordinary housewife. I threw them away. All of them.

When we are young, we operate under many false assumptions. One of mine was that my mom would always be around. Before she died of cancer, I received one last letter from her. The handwriting was cramped with pain, the thoughts were slightly disorganized, and there were many spelling mistakes. (I had never known my mother to misspell a word.) She made no mention of weather or crops. Instead she assured me that, despite her death, all would be well. She wrote of her love for me and her regret that she would miss seeing my wedding and her grandchildren. She listed my strengths and encouraged me to stand with the rest of the family as we struggled with grief.

How I wish now for a letter telling of laundry drying on the line.

Shelly Ungemach

Monterey, Massachusetts

It was just a plain white box, carefully wound in masking tape, “Letters from Brenda” written neatly on the top. In it was every letter I had ever written to my mother. She hoped they would help me with my writing, she said sadly when she gave them to me. They had become too painful for her to have around.

I took the box, thanked her, and tucked it away on a high shelf.

That was four moves ago. Each time, I have carefully taken the box down from its hiding place, holding it gingerly, as if it might break. The tape has long since yellowed and curled around the edges.

The first letter must have been sent when I was sixteen years old and had just been placed with foster parents by the courts, because I was an incorrigible runaway. My fosters were cool; they let me smoke. My foster mother, Cheryl, had a job that kept her away from home most of the day. My foster father, Joe, stayed home, fed the horses, and worked on the cars. He and I became lovers.

I wrote my parents quite regularly, telling of all the fun I was having in school and with my new friends. None of it was true. I had no friends; my foster father saw to that immediately. His jealousy made me feel special.

Joe dealt weed and uppers at truck stops in the evenings. I became his partner in crime. Cheryl never commented on the pet names we had for each other, the subtle looks between us. I convinced myself she didn’t know what was going on.

The day I was to graduate from high school, I discovered that I was pregnant. Joe never even blinked when I told him. For a moment I thought he was angry with me. Then a smile came across his face, and we began to come up with a plausible story so that no one would know it was his baby. I needed to be seeing someone, or else how could I get pregnant? Joe and I decided that I would attend several all-night parties following graduation, and a month or so later I would suddenly “discover” that I was pregnant.

When the time came for me to tell Cheryl, I carefully rehearsed the story. She was calm and accepting. Much later it occurred to me that she had not been the least bit surprised.

Everything happened quickly. Within days, Joe and I had moved to a furnished apartment in Santa Barbara. Cheryl was to follow with our belongings in a month or so. They explained that, because I was on probation, the state could take my baby from me. “Running” was in my best interest.

During the week, Joe and I lived as man and wife. Cheryl came up on the weekends. My letters home continued. I spoke of a nonexistent job, of the hot summer days, and of the horse that I no longer had. Each Sunday, Cheryl would take these letters back with her to be postmarked from the old address.

I never wrote of the hard labor that I endured with Cheryl by my side. (Joe didn’t even come to the hospital.) I didn’t tell my mother that she had become a grandparent.

My son was born small, due to my diet of cigarettes and coffee. He stayed in the hospital for three weeks. The first time I saw him he had needles and tubes everywhere. That night I wrote a long letter to my parents. I told them I was planning a trip with a girlfriend; we were going to Santa Barbara.

Eventually I deduced the truth about Joe and Cheryl: I had been nothing more than an incubator to them. They were convinced that this “incorrigible runaway” would simply hand over her baby. They were wrong.

I kept my child, married, and moved on with my life. I had almost forgotten about those letters until my mother handed them back to me, very much aware now that they contained nothing but lies.

I am fifty, and that box of falsehoods sits on the top shelf of yet another closet. The tape has almost pulled free. The box remains unopened.

Brenda Rae Souza

Santa Maria, California

“Why don’t you move in with us for a while? Take it easy. Take some of the pressure off.” My brother-in-law Bobby made this offer to me one Sunday afternoon in March. I was going through a divorce and had just gotten out of the hospital after cracking up for the fourth time.

My brother-in-law’s full name is Bobby Dean Winchester, and he’s a country boy from Guthrie, Kentucky, the youngest of a large brood. He built his own business from the ground up, and when times are tough he gets by with the help of two choice phrases: “Serenity now” and “Fuck it.” He’s got a wife (my sister), twin daughters, two rock-eating dogs, and a couple of ragamuffin cats to support. Somehow he makes it look easy. My favorite story about Bobby is that, when he was learning his ABC’s, he thought “el-em-en-oh-pee” was one letter.

On the Sunday afternoon Bobby made that offer of help, he wrote a letter of sorts to me. It was addressed with a careful hand, and it read: “I don’t care that you just fell apart. I’m proud of you and always have been — no matter what.”

Lori Kupp

Nashville, Tennessee

My parents were living in Puerto Rico when my father suffered a severe stroke. Deprived of speech, movement, and the job he loved, he cried out during the night and shouted, “No, no, no!” during the day. My mother was frail and had difficulty dealing with him.

I was a cloistered nun at the time, and my abbess thought it was God’s will that I return home to help my mother. So I flew to Puerto Rico.

Most of my parents’ friends found it “too difficult” to see my father that way, but Padre Vittorio continued to visit, both as a priest (to administer the sacraments) and as a friend. He was handsome, funny, and warm.

When I returned to the monastery several months later, Vittorio and I began writing to one another. Though he spoke fluent Italian, Spanish, French, and German, his English was dreadful. He suggested we correspond via cassette tape so that he could practice: Vittorio would record a letter and mail it to me. I would then tape over his message with one of my own.

For three years my father’s condition steadily worsened, and I traveled back and forth between the silence of the monastery and the sensuality of that tropical island. Despite the exhausting task of caring for my father, I was intoxicated by the sights, scents, and colors of Puerto Rico, and I missed the island terribly when I was away. Each return to the monastery was more difficult than the last.

Vittorio’s letters helped relieve my homesickness. He and I said things on tape that we did not have the courage to say in person. We shared the yearning that had first drawn us to religious life, as well as our struggles with the Church, loneliness, and asceticism. We were falling in love.

Just before my father died, I left the monastery, and Vittorio left the priesthood. We married and had five wonderful years together. Then Vittorio died of pancreatic cancer, leaving me with two toddlers.

When I finally mustered the strength to sort through his things, I found a box of cassette tapes on a shelf in his closet. He had saved all our correspondence. That night, after putting the children to bed, I sat down to listen to the tapes, looking forward to hearing his voice again.

I’d forgotten that I’d taped over his responses.

The tape I randomly selected was one of the last I’d sent before leaving the monastery. Though my words seemed harmless enough, the seductiveness of my tone was undeniable. Hearing such unabashed sensuality in my voice horrified me. During Vittorio’s illness, I’d wondered whether his terrible suffering might have been God’s punishment for our broken religious vows.

Sick at heart, I destroyed every tape, as if that might erase my guilt. Now, thirty year later, I’d give anything to have them back, to remember those wondrous, euphoric days and the man who taught me so much of what it means to be a flesh-and-blood woman and a compassionate human being.

Beryl Singleton Bissell

Schroeder, Minnesota

I have a bundle of thirteen letters my father wrote to me when I was five. He was a soldier then, drafted into the German Army to fight a war he did not believe in. I was a little girl living on a farm in the foothills of the Austrian Alps.

There are long epistles and brief greetings. Some are written in ink, others in pencil, all carefully printed for easy deciphering by my five-year-old eyes. The envelopes show military postmarks with eagles and swastikas and my father’s identification number: 41672 D. Some are written on forms printed with Christmas garlands or the message “Victory will come!” They came from Hungary, Croatia, Albania. In one there is a drawing of a mountain landscape. “We are where the dot is,” wrote my father. I knew only that he was far away.

The first letter is dated December 28, 1943, shortly after the last time I saw him, during an unexpected Christmas visit. The final letter is dated April 17, 1944, twelve days before he died — “for the glory of the fatherland,” according to government officials. He was thirty-two; I was not yet in school. These letters are my father’s legacy to me. Although they cause me much pain, I must read them, for they tell me I was loved.

One letter is a greeting on my birthday. “I remember so clearly how you tumbled into this world five years and five hours ago,” he writes in large, shaky capitals, due to an injured hand. Others are full of questions: “Has the calf been born? Are you walking barefoot yet?”

He gives little lessons about the places in which he finds himself. He describes the landscape, the costumes of the people. He tells about life in a war, about living in “underground houses” called bunkers, and how the candles go out when there is shooting. In his last letter he paints this scene: “There are small horses running around. But many are dead and have stopped moving. Almost all the people in the village have left. Only the chickens remain, and the soldiers are eating those.”

In deep winter my father wrote, “Oh, when the trees will be as white with blossoms as they are now with snow, how beautiful that will be.” And in April, not long before his death: “It was warm today. I heard a lark sing for the first time, and I saw two yellow brimstone butterflies.” He often wrote of the constellation Orion. “When I come home, we must look at Orion together again. When I see the bright three stars of his belt now, I always think of you.”

He did not come back to look at the stars with me, but he left me this bundle of letters and an image of myself: an eager girl who loved to pick flowers and wanted to please her father. And I see my father: a soldier, vulnerable, full of longing; a man who in the midst of destruction was buoyed by the beauty of a butterfly and the thought of his small daughter far away.

Christine Saari

Marquette, Michigan

I am an only child, and my father left us when I was just two years old. I have one vague memory of a smoky taproom where I sat on the bar while my handsome daddy laughed and drank with a beautiful stranger. My mother never told me why he went away. I guessed that I deserved to be abandoned.

From my early teens on I believed that no man would ever really love me. The best I could hope for was fleeting connections or sexual favors traded with the handsome, slightly dangerous types I was attracted to. I told myself this was good, because it meant that I was free.

An unplanned pregnancy and subsequent short-lived marriage left me on my own with my only child at the age of twenty-five. Still I couldn’t leave the handsome, dangerous ones alone. Time after time I made the same wrong choices and paid the same price, ending up bruised and solitary.

In my early fifties I made an uneasy peace with my past. Although I’d never have a real partner, I convinced myself I was happy. Friends were enough. Freedom was more important. Love was overrated.

One day my mother fell. A few months later, I was knee-deep in dusty boxes in her basement, trying to salvage valuable memorabilia before sending her off to a retirement community. There wasn’t time to sort carefully through the papers. I took home four grocery bags full of pictures and a big stack of Manila envelopes, notebooks, and binders. I figured it would be fun to sift through them and reconstruct my mother’s life, and maybe some of my own.

For several nights, I sat up late in my kitchen, cataloging my treasures. I found autographed pictures of Benny Goodman and Harry James, a name tag from a USO dance that read, “Hi, Soldier, I’m Betty!” and pictures of all the servicemen my mother had written to. They’d sent her patches from their uniforms, Nazi insignia, Japanese money, scraps of parachutes. I was right. This was fun.

Then I found the stack of letters: years of correspondence between my mother and my father’s parents, between my mother and the courts, and, yes, between my mother and my father. One letter was addressed to me. It was still sealed. I would have been eight years old when it was delivered. With trembling hands I opened it and read: “I am afraid I am just a little bit late in writing to thank you for the little swan that you sent me for Christmas.”

I never knew my father had written to me. I never wrote to him, and I certainly never sent him any presents. My mother must have sent the swan to him in my name. I read on:

“I think he is very nice and quite a handy gadget. He sits on my dresser, and when I come home from work at night I put all the odds and ends that I have in my pockets in the swan, so I know where to find them in the morning. I think you did a very nice job making the little fellow, and I like him very much.”

I knew the swan he was talking about. I remembered making it out of clay. I could picture it clearly, the shape of its head, the cobalt blue glaze. But I never knew my mother had sent it to him. There was a picture of him enclosed with the letter and mention of a little bracelet he was sending along, but there was no bracelet. It must have come in a separate box. Maybe I even received it. I wondered which of the bracelets that I thought had come from my grandmother really had come from him. The letter was signed: “Lots of love, Daddy.”

I never knew my father. My mother said nothing about him while I was growing up. Now here was proof that he hadn’t just walked away without looking back. He wasn’t just another handsome, dangerous type. His letters revealed a lonely, unhappy man who regretted the pain he had caused; a man who perpetually decided to do one thing with great resolve and then did the opposite. Suddenly I was crying. In my whole life, I hadn’t cried once about my dad. Now I understood what he and I had lost.

Name Withheld