Needles make me queasy. When James shoots up, he often goes into another room to spare me the sight. Even if I am sitting only a few feet away, he turns his back and asks that I not look, because he never wants me to see the needle go into his arm.

What I do see is the blood trickle from the vein afterward, like red molasses. He sucks on it to get the bleeding to stop, the way I would if I pricked my finger. Then his face goes slack and his voice gets raspy and his whole body changes. Even though I didn’t see the injection, this transformation is jarring, and I can’t help but wonder how, after a life of straight A’s and honor societies and college degrees, I am drawn to someone like James, whose life has been the opposite. I suppose I am fascinated, the way I am by other planets. I want to know what Saturn’s rings are made of or what the mountains of Mars are like.

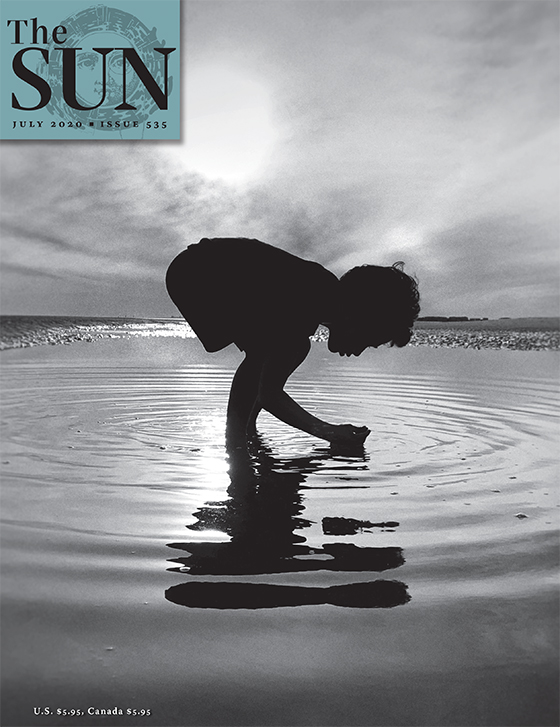

Sometimes, to distract myself, I mentally travel to another place while James shoots up: picking strawberries with my grandmother; sitting beneath the dogwood tree in my parents’ backyard; standing on the beach, the sun warming my face. Sometimes I think about happier times with James: the time he gave me a homemade valentine, or the night he drove all the way from New Jersey to Brooklyn because I said I couldn’t sleep without him.

“I’m sorry I exposed you to all this,” he says.

“I know you are,” I say, a heaviness in my chest.

James is high again tonight. As I step off the train in New Jersey and walk toward him, I can see it in his lopsided grin and how his pupils are pinpricks floating in the chocolate of his irises. It is April 2019, and James and I have been dating since November. I knew he was a heroin addict when I met him through a mutual friend. James was kind and up-front about his habit. I researched heroin use, so when I first saw the signs of it — slow breathing, flushed skin, a tendency to nod off, slurred speech — I was familiar. The symptoms are all present tonight: James can’t remember what he’s just said. He is sweating. His words come at the pace of a thick syrup, sweet and slow moving.

“I wanted tonight to be a good night,” he says, wrapping his clammy fingers around mine and gently squeezing. I sigh, that heavy feeling in my chest again, and squeeze back.

James lost his driver’s license a month ago, so he asked a buddy from work to drive him to the train station to pick me up tonight. Before we can head to the beach, we have to be driven to James’s dilapidated car — the one with no heat, a talent for leaking oil, and a nearly flat tire — at which point I will drive us, clunking, to the shore. I’ll do just about anything to see James, including taking a two-hour train ride from New York for just one night together. He and I are that crazy about each other.

On the way to Seaside, James lets me know that we have to meet his dealer first. I’ve stopped putting up a fight when James needs to buy drugs. I used to cry, provide ultimatums, give him the silent treatment. Now I try to believe he has it all under control, the way he tells me he does — that he knows just how much to take, never buys from people he doesn’t know, never shares needles. Also, when James is high, he is at his most affectionate. He becomes generous with hugs. He kisses my face all over, eyelids and all. I am ashamed that I like this about his addiction.

Tonight, though, I’m annoyed. This extra pit stop will eat into our time together.

“Is this really necessary?” I ask.

“C’mon, babe,” he says. “You know how it is. I already feel bad enough.”

When we finally get back on track, it’s nearly 8 PM. I drive along Route 35 and try to forget about the fact that we will eventually have to break up if this doesn’t stop. We tell ourselves the biggest problem between us is that James wants children — drooling babies, pacifier-sucking toddlers — and I don’t, but it’s also the heroin. As I drive, I see the beach at the end of every side street, the sand splattered with the last orange streaks from the sun. Everything seems most beautiful just before it sets.

I know you’re not supposed to fall in love with an addict, especially one who’s still using. One night, while James snored softly next to me, I googled “addicts, relationships.” The first website said, “As long as someone is in the midst of their addiction and not receiving help, a relationship with an addict is virtually impossible. An addict will do everything to keep using, including lying, cheating, and stealing.” James has never done any of that, but my friends are still upset with me and concerned for my safety. Addicts are unpredictable, they say. Manipulative. Dangerous. But they don’t see the sweet parts of James, the ones that make leaving him so hard.

“Do you think we should pick up ice cream?” he asks.

“Sure,” I say. James is good like that: he bothers to ask me what I want, would get me whatever I want.

We’ve rented a motel room right on the boardwalk, where everything is salt blasted and sun weathered. It’s nearly ten by the time we get there. The boards creak beneath our feet. There are ants in our first room, so we ask for a new one. In our less-bug-filled room, we decide to shower before we go out. While I go into the bathroom, James does more dope. I am embarrassed by his addiction, embarrassed that I have to help him keep it from some people we know and love. But telling everyone wouldn’t work either. Like my friends, they’d have notions about James; they’d see him as the websites do — scary, false, manipulative — and he is not any of those things.

I step into the shower and let the water run over my hair. James has brought soap and shampoo.

“Want me to get your back?” he asks.

He ends up washing my whole body. He lathers the soap until it foams like the crest of a wave, then runs the washcloth over my shoulder blades. The scrubbing is satisfying and not too hard. He turns me around and washes my breasts and legs, wedges the washcloth between the cracks of my toes. His attention to detail is almost holy. James is nothing if not thorough, nothing if not loving. I close my eyes and imagine the life we could have together if he would just get everything under control.

After James showers, we leave to get food. It’s late because of the stop we had to make. As we walk along the boardwalk, all the arcades and shops are shuttered — the Frog Bog, Planet Candy, Sonny’s & Rickey’s. The rides are still. The waterfalls at Adventure Golf have been turned off, and the stuffed animals are tucked behind metal gates, their fluffy arms poking through the bars. I had a different vision of how this night would go. I pictured everything lit up and James winning a prize for me.

The only things open now are the bars, a few restaurants, and some stands selling cotton candy and zeppolis — fried bread dusted with powdered sugar. The air smells like cookie dough, and I remember hearing once that sugar is as addictive as any drug. I wonder about the line between James and me, how blurry it might be. Aside from weed, I’ve never tried anything illegal. Sometimes I wonder what it would take to get me to do it; how people make their way to injecting a drug into their veins. For James it started with pills. Then a friend introduced him to heroin.

James takes my hand and swings it like a pendulum as we walk into a restaurant. While we wait to be seated, he takes apart the device that will buzz when our table is ready. He is always curious, always tinkering. Like a bear cub, he paws at things. He is a carpenter, and his hands are a mess of cuts and calluses from sanding doors and large pieces of plywood; his work boots are crusted with dried spackling mud. When something goes wrong — like the time he dropped a bucket of paint while on the phone with me — he asks, “Why me?” as if the universe has decided to make his life difficult. He grunts when he’s frustrated, but he forgives easily.

We finish eating at midnight and leave the restaurant. The moon is a fish eye, yellow and bulbous, caught between the spokes of the Casino Pier Ferris wheel. The sea churns as we move closer to the water, the wind and tide pushing and pulling the waves in different directions. We’ve brought weed and zeppolis with us, and towels from the motel. When we find a spot, I feel dizzy with joy. We spread our towels and anchor them in the wind with our bags and shoes. I take poorly lit selfies of us and show James the pictures.

“That’s a fake smile I’m making,” he says. “I can’t give a real smile when I’m high.” He sighs. I wonder if James can truly be happy while he’s on drugs. I am angry that he cannot be completely present with me in this moment. And then I think how unfair that expectation is.

Neither of us has ever had sex on the beach, and we decide that this will be the night. James keeps watch for passersby while I try to pull off my leggings, but I am laughing too hard. James keeps falling on me. We both laugh, the kind of laughter where you can’t breathe. Then he kisses me, and I wrap my arms around him. I can see the stars, and I think about the planets again, how James and I might as well be from different ones. Afterward I look at the moon hanging above the sea and worry that James will die of an overdose, that one day his heart — which I can hear beating as I lie with my head on his chest — will just stop. I sit up and look at him. His eyes are narrowed, watching the water. The smoke from our blunts is burning my eyes.

“What are you thinking about?” I ask.

“Life,” he says. “I had a different picture of how things would go.”

“You could still change it,” I say.

“I know,” he says. “I know.”

This relationship won’t last forever, but I can’t think of what does. Even the shore is eroding. We make our way back to the boardwalk, the sand cold on our feet, our zeppolis leaving a trail of powdered sugar, as if we plan to find our way back some day. As we reach the motel, two cops pass by, heading toward the beach.

“They almost caught us,” James says, and he kisses my forehead.

When we get back to the motel room, James does more dope. I wonder if he will ever stop. He says he is trying. He tells me how hard it is. I watch his face droop and feel him slip away into another world. I wish I had more time with him — the version of him that can smile for real, that can stay awake without nodding. We lie in bed, arms around each other, and I breathe in the smell of his hair: the odors of shampoo and the sea. I interlace my fingers with his, and we both squeeze. I have to take an early train back to work in the morning; James needs to put up sheetrock in new houses. I should end this. I shouldn’t be around it. But then I think about James and how carefully he carries my heart in his hands, as if it were a tiny bird, and I know that I’ll call him again tomorrow afternoon.

When the sun rises a few hours later, I hear the gulls cawing through a window we left open. There is sand in the bed. I try to kick it off the sheets but somehow get more stuck on me. The ice cream in the fridge is starting to melt and drip from the door, and ants are trickling in — a long black line, coming for all that sweetness.