The debate over illegal drugs in the U.S. has long focused on legalization versus increased prosecution, treatment versus harsher sentences. But what’s been missing on both sides of the debate is a meaningful understanding of the history and politics behind drug production and prohibition. What’s the relationship, for example, between the Cold War and skyrocketing drug use in the U.S. and Europe? And why is it that, in the nearly one hundred years since the U.S. passed its first antidrug law, the global traffic in drugs has grown astronomically?

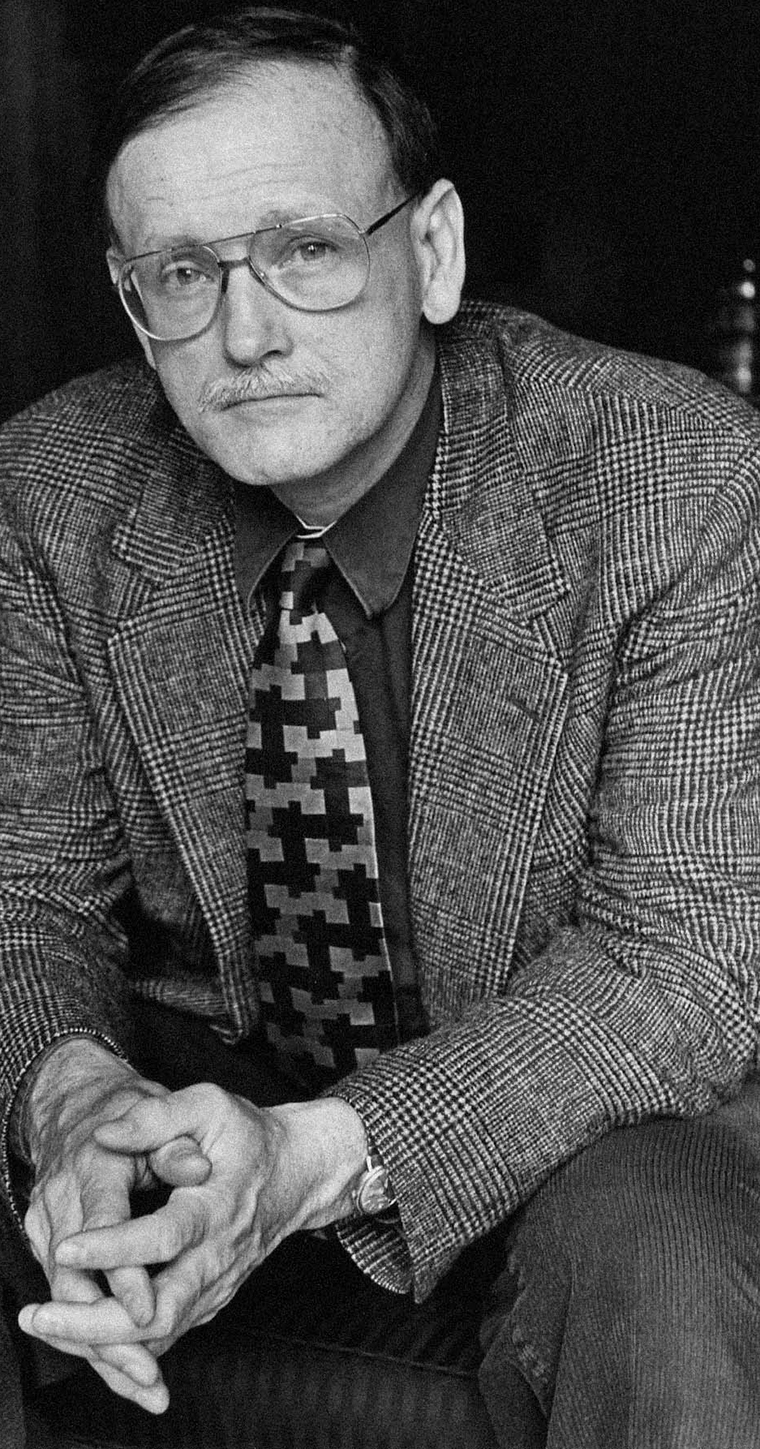

Alfred McCoy, author of The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade, has literally written the book on the complex relationship among drugs, prohibition, and international politics. Now in its third edition, the book got its start in 1970, when McCoy’s editor at Harper & Row suggested he write about the explosion of heroin use among U.S. soldiers in Vietnam. At the outset of his globe-spanning journey, McCoy went to Paris for a meeting with General Maurice Belleux, former chief of French intelligence for Indochina, who revealed to him that the CIA, like its French predecessor, was involved in the opium trade. When Beat poet and antiwar activist Allen Ginsberg met McCoy at an antiwar rally and heard what he was writing about, he sent him years’ worth of unpublished dispatches from Time-Life correspondents — lifted from the magazine publisher’s files — documenting the involvement of U.S. allies in drug trafficking. Then came the stories from Vietnam veterans of CIA helicopters transporting opium in Laos, destined for U.S. troops in South Vietnam. That’s when the death threats began.

Sometimes they were more than threats. While he was doing research in Laos in 1971, members of the CIA’s Secret Army ambushed and shot at him and his colleagues. But he persevered, going from the Hmong villages in the Laotian highlands, to the homes of major drug lords, to the camps of opium armies. Everywhere he went, he asked about the history of the drug trade in the region, starting in the past, when the trade was legal and answers were easy, and working his way up to the present with questions that were oblique and more discreet. His strategy worked.

Despite the CIA’s attempts to suppress it, The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia came out in 1972. McCoy revised the book in 1991, shortening the title and including the story of the CIA’s involvement in Afghanistan and that country’s subsequent increase in opium production. For the 1991 edition, McCoy wrote, “Over the past twenty years, the CIA has moved from local transport of raw opium in the remote mountains of Laos to apparent complicity in the bulk transport of pure cocaine directly into the United States.” He could now point to a pattern of how, over and over, “America’s drug epidemics have been fueled by narcotics supplied from areas of major CIA operations, while periods of reduced heroin use coincide with the absence of CIA activity.”

Controversy continues to follow McCoy. A few days before I interviewed him at his office at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, a crowd of protesters had gathered outside his building. The city of Madison had turned down a request by a local Hmong politician to name a park after General Vang Pao, a leader in the CIA’s Secret Army during the Vietnam War. One of the reasons the city gave for its refusal was McCoy’s account of Vang Pao’s involvement in the opium trade and his disregard for the lives of the Hmong people who fought under him on behalf of the CIA. The protesters included veterans of Vang Pao’s army — the same troops who had ambushed McCoy in Laos years ago.

In addition to writing The Politics of Heroin, McCoy has spent years investigating the drug trade in Australia and written and edited other books on drug trafficking, Southeast Asia, and the Philippines. More recently, he has worked as a consultant and commentator on television and film documentaries about the global drug trade. The latest revised and updated edition of The Politics of Heroin — and the last, McCoy says — has just been released by Lawrence Hill Books. It is, he says, “a life’s work.”

ALFRED MCCOY

Jensen: What do politics and heroin have to do with each other?

McCoy: Narcotics and addiction are not simply products of social deviance or individual weakness. Narcotics are major global commodities, and commodities are the building blocks of modern life. They shape our culture. They shape our politics. Whether we encourage trade in a particular commodity or attempt to prohibit it, both acts are intensely political.

Jensen: Different drugs seem to go in and out of favor. Why is heroin so significant?

McCoy: Over the last three centuries, the global narcotics trade has been shaped by the traffic in opium, the most venerable of all drugs, and heroin, its modern derivative. Opium’s original home was the eastern Mediterranean. But by the eighth century it had spread, both its cultivation and trade, along the mountain rim of Asia all the way to China. Still, for most of its four thousand years of recorded history, opium remained limited in both its production and use. It didn’t become a major commodity until the nineteenth century, when consumption rose dramatically in both Asia and the West. China, which was plagued by political and cultural turmoil at that time, appeared to have an almost limitless appetite for opium. And there was a tremendous rise in opium’s use for patent medicines in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

In the late nineteenth century, the European pharmaceutical industry discovered diacetylmorphine — a chemical compound created by bonding morphine from the opium poppy with a common industrial chemical, acetic anhydride. In 1898, the Bayer Corporation launched diacetylmorphine as a cure for infant respiratory ailments, giving it the short, catchy trade name “heroin.” (A year later, Bayer came up with an analgesic that it felt was also ideal for children’s respiratory ailments, and it gave that the trade name “aspirin.”) Heroin was widely used and abused. Historian David Musto has estimated that there were three hundred thousand American opium and heroin addicts in 1900 — primarily women. At that time, women were banned from barrooms and confined to a nurturing role, so this highly addictive drug marketed as a treatment for children’s ailments was a natural for them. You can find an evocative and accurate depiction of this problem in Eugene O’Neill’s classic play Long Day’s Journey into Night, about his own mother’s addiction.

Meanwhile, in China, the government did a survey in 1906 and found that 13.5 percent of its adult population was addicted to opium. Today the highest level of narcotics addiction in the world, according to the United Nations, is in Iran, at about 3.5 percent.

We’ll never know what might have transpired if Western intelligence agencies hadn’t used the power of the underground drug economy and its criminal syndicates to fight communism during the Cold War. If the CIA hadn’t existed, would we have the levels of addiction we see today?

Jensen: What is it in the U.S.?

McCoy: About 0.7 percent. China’s 13.5 percent figure, and the scale of addiction it represented, was so astronomical that it became an international scandal and sparked a global movement for opium prohibition. Around the turn of the century, this movement merged, ideologically and politically, with the larger temperance crusade in Europe, the United States, and the English-speaking colonies.

America’s early involvement in opium prohibition was something of an accident. When the U.S. had conquered the Philippines in 1898, it had acquired, along with seven thousand islands and their six million Filipino inhabitants, a state opium monopoly. In response to strong moral opposition by Protestant churches, the U.S. colonial government prohibited opium consumption in the Philippines in 1908. That effort led the United States to chair the Shanghai opium conference a year later — launching our modern drug diplomacy and leading to the U.S. Harrison Anti-Narcotics Act of 1914, the first of our domestic antidrug laws.

Since World War II, the United Nations has passed a succession of conventions on drugs, moving from voluntary compliance to compulsory international enforcement. The interweaving of these international conventions with domestic legislation has created a very powerful worldwide prohibition regime.

If we look back at the history of this regime, we find that the attempt at global prohibition has actually stimulated the traffic in illegal drugs. In 1998, the UN estimated international drug trafficking at $400 billion a year, equivalent to 8 percent of all world trade — larger than steel, automobiles, or textiles. So the international trade in illicit drugs is larger than the trade in one of the three human fundamentals: clothing.

Prohibition is the essential precondition of the drug traffic’s enormous power and profits. By driving narcotics — heroin and cocaine — into an underground economy, the prohibition regime assures the drug traffic all it needs to survive prohibition: three million syndicate criminals, millions more highland farmers, and the greatest profits of any human enterprise. In the last half century, these commodities have become so profitable, so powerful, that they can corrupt the police of major cities, transform nations into narco-states, and fuel protracted covert wars.

Jensen: Didn’t we miss an opportunity at the end of World War II to drastically reduce the traffic in illegal drugs?

McCoy: There was a confluence of factors in the late 1940s that might have led to a substantial reduction of the global traffic in illicit drugs. The first factor was the increased effectiveness of the global prohibition regime during World War II. The second was the wartime disruption of all trade and the rigid security imposed upon ports around the globe to stop sabotage, espionage, and the like. But the most important factor was the Communists’ rise to power in China in 1949. In the space of about five years, they ran the world’s most successful opium-eradication campaign, eliminating mass narcotics addiction and the world’s largest source of opium.

We’ll never know what might have transpired if Western intelligence agencies hadn’t used the power of the underground drug economy and its criminal syndicates to fight communism during the Cold War. If the CIA hadn’t existed, would we have the levels of addiction we see today? I can’t say. But I can say that covert operations played a significant role in the expansion of drug trafficking after World War II.

In the late 1940s, the Iron Curtain came crashing down along the southern border of the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. In one of history’s ironic accidents, this border was also Asia’s historic opium zone, a mountain rim that stretches five thousand miles, from Turkey to Thailand. Over a period of forty years, from 1950 to 1990, the CIA fought three major covert wars — not just operations, but actual secret wars — along this rugged southern frontier, this soft underbelly of communism. First, there was the CIA’s attempt to invade China from the Burmese borderlands during the 1950s. Then there was the CIA’s secret war in Laos from 1964 to 1974. Most recently, there was Afghanistan, where the CIA backed the mujahedin guerrillas against the Soviet occupation from 1979 to 1992.

These were large wars and long wars. The U.S. was involved in World War I for less than two years, and World War II for just four. By contrast, these are ten- and twelve-year wars that, in some cases, involved massive military operations. The largest bombing campaign in the history of warfare was the U.S. air operation in Laos in support of the CIA’s secret war there. From 1964 to 1974, the U.S. Air Force dropped 2.1 million tons of bombs on tiny, impoverished Laos — the same tonnage that the Allies dropped on both Germany and Japan in all of World War II.

These wars were generally fought at the margins of states that didn’t support our efforts, in ethnic-minority-populated areas where the main cash crop was opium. The CIA found out that, to fight covert wars in such remote regions, it had to ally itself with local warlords — who, in turn, used the CIA’s arms, protection, and logistics to transform themselves into drug lords.

At the start of each of these wars, opium production was both limited and localized. Very quickly, however, both the scale and scope of the traffic expanded to fund the war. Then, when the operation was over, the region became a covert-war wasteland in which only the opium poppy would flower. Because these wars were conducted outside conventional diplomacy and beyond Congressional oversight, there was no postwar settlement, no treaty, no reconstruction. Officially, they never happened. In the absence of any cleanup, expanded drug trafficking served as an ad hoc form of postwar reconstruction.

In the late 1930s, British colonial authorities in northeastern Burma estimated annual local opium production at about eight tons. By 1970, following the CIA’s covert war in the Burmese borderlands, it was three hundred tons. The net result of the Agency’s intervention was that northeastern Burma went from localized opium trade to being the heart of the global heroin traffic. After the CIA’s secret war, Laos went from similarly limited production to being the world’s number-three opium producer today.

The purest case of transformation, though, was Afghanistan. At the time we got involved in Afghanistan in 1979, its annual opium production was no more than two hundred tons, with trade limited to Central Asia, particularly Iran. There was no heroin production, and no international trafficking. From 1981 to 1991, opium production in Afghanistan grew to two thousand tons — a tenfold increase. Just two years into this secret war, Afghanistan, in concert with western Pakistan, had become the world’s largest heroin producer, supplying, according to the U.S. attorney general, 60 percent of U.S. heroin and about 80 percent of Europe’s. Today the world’s three leading producers of illicit opium are all former battlegrounds in the CIA’s secret wars: Afghanistan, Burma (now Myanmar), and Laos.

Jensen: How is it in the CIA’s interest to do this?

McCoy: Basically, when the Agency mounts a covert operation, a handful of operatives form an alliance with one or more local warlords. The warlords raise an army to fight the CIA’s battles, and the agents reciprocate by providing their warlord allies with arms, supplies, funds, food, and political support. These agents do this not only to make that tribal leader more militarily effective, but also so he’ll increase his power over his tribe and draw more recruits who will fight in a more determined and committed way.

Now, along this mountain rim of Asia, from Turkey to Thailand, this southern frontier of anticommunist containment, the sole cash crop was opium. So as the tribal warlord grows in power, he takes over the opium trade, and thus takes over the household economy of every farming family. It’s in the CIA’s interest to tolerate opium traffic because it increases the political power of the Agency’s chosen ally and makes the CIA’s covert army more effective.

Moreover, as the fighting gets going and the men are drawn into the war, the male labor pool drops. Opium harvesting is, in many highland cultures, women’s work. The men may clear land and plant the seed, but the women harvest, and a poppy field can stay in production in Southeast Asia for as long as a decade. This means the women are productively employed in delivering a high-income cash crop, reducing the otherwise prohibitive cost of supporting several hundred thousand dependents of these tribal armies.

Jensen: Where is international law enforcement while all this is going on?

McCoy: Crucially, these covert war zones become enforcement-free zones, where international and local law enforcement don’t venture. A classic case of this was Afghanistan in the 1980s. During that decade, when literally hundreds of heroin kitchens lined the Afghan-Pakistani border, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration [DEA] had a detachment of seventeen officers in the Pakistani capital of Islamabad. These officers conducted no significant investigations and made no seizures or arrests. They stayed entirely out of the Northwest Frontier province of Pakistan, where the heroin industry was sited, because the traffickers were our covert-action allies.

The situation in Central America during the Contra campaign was even worse. After the left-wing Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua in 1979, the CIA launched a covert war on that country by backing the opposition Contra forces. The DEA office in Honduras, a frontline state in this secret war, began collecting intelligence that the CIA’s local military allies were involved in cocaine smuggling, so Washington closed that office. Moreover, the CIA formed an alliance with a top Caribbean cocaine smuggler named Alan Hyde, the “godfather” of the Bay Islands off Honduras. In exchange for the use of his port facilities to supply the Contras, the CIA protected Hyde from any investigation for six years — at the peak of the crack-cocaine epidemic in the U.S. According to the CIA inspector general’s later report, top Agency officials protected Hyde even though they had intelligence from the DEA and U.S. Customs that he was smuggling cocaine shipments into the U.S. So under these covert-war conditions, drug traffickers could operate with impunity.

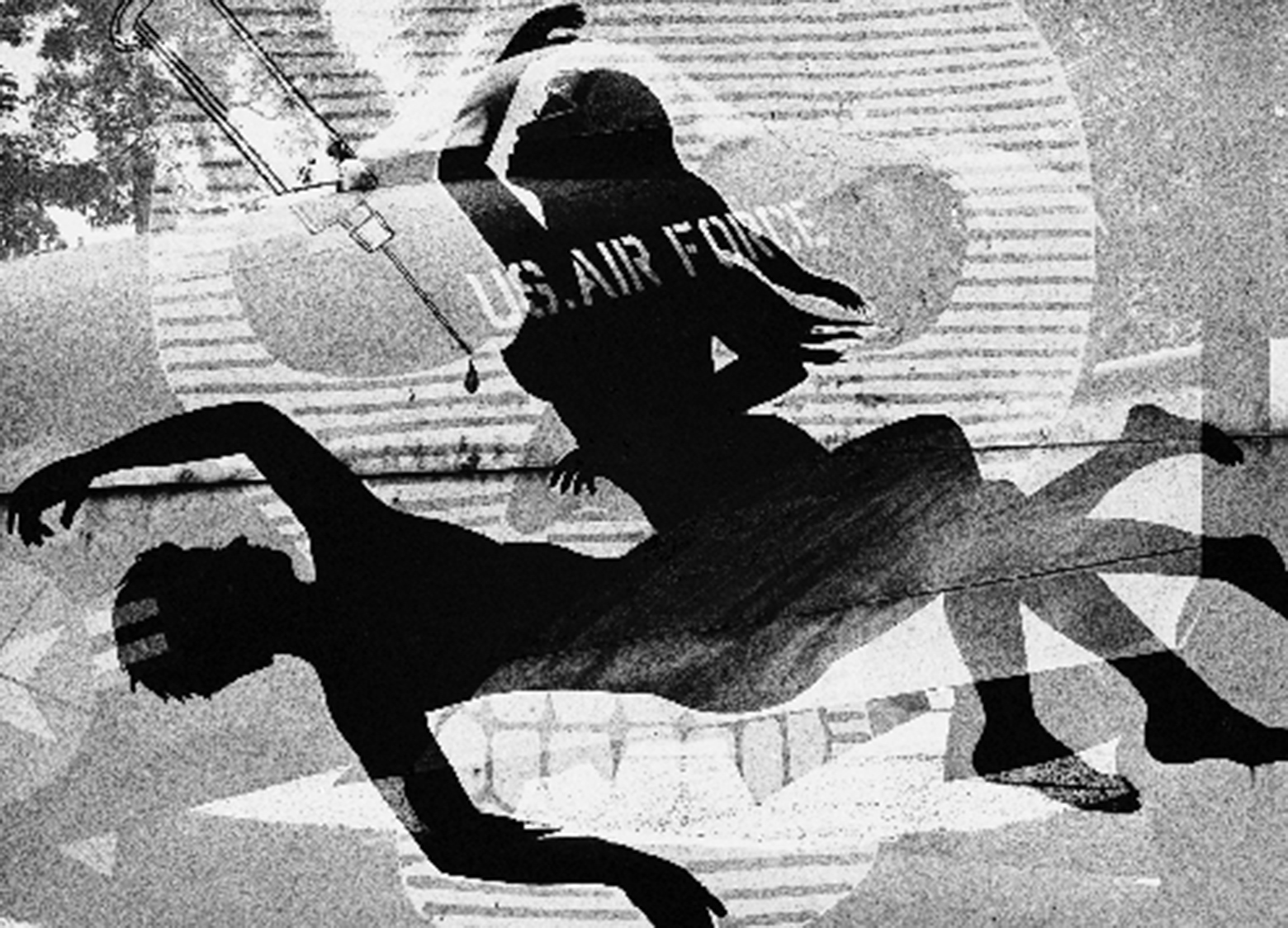

The CIA’s warlord allies built a complex of seven heroin refineries at the heart of the Golden Triangle, where Burma, Thailand, and Laos converge. Let me make this clear: all the laboratories were built by current or former covert allies of the United States. And they began producing high-grade heroin for shipment to South Vietnam. The local Asian addicts were opium smokers, which means the heroin was targeted purely at American troops.

Jensen: Hasn’t the CIA also allowed its airplanes to be used for transporting illegal drugs?

McCoy: I know of one particular case of that, in Laos. Let me give you some background: During the Cold War, the Soviet Union and the U.S. went to the brink of nuclear war over Laos before stepping back and negotiating a treaty in 1962 in which both sides agreed to remove all combat forces from the country. Two or three years later, the Vietnam War heated up, and suddenly the North Vietnamese were sending troops and supplies from the panhandle of North Vietnam, down through southern Laos, and into South Vietnam: the famous Ho Chi Minh Trail. Unless the U.S. could cut off that supply route, we had no hope of winning our war of attrition in South Vietnam. Suddenly we had to be involved in a country where we could not be involved. That led to the secret war in Laos, in which the CIA turned the Hmong tribesmen into its so-called Secret Army. The Hmong, who were the main opium growers in the region, lived on highland ridges above three thousand feet elevation. With road travel dangerous to impossible during the war, their villages were linked together by a network of two hundred dirt landing strips accessed by a CIA airline called Air America.

In 1971, when I was doing research for The Politics of Heroin, I hiked into northern Laos, at the western edge of the Plain of Jars region. I went from house to house in the two Hmong villages where I was able to conduct my survey, and the picture was pretty clear. Farmers were harvesting about five to ten kilos of opium each. At the end of harvest season, they took the pungent raw opium, wrapped in banana leaves, down to the landing strip — and the farmers’ stories were absolutely consistent on this score — where an Air America helicopter landed. Hmong officers in the CIA’s Secret Army got out, paid the tribesmen cash for their opium, loaded it onto the helicopters, and flew away in the direction of the CIA’s secret base at Long Tieng.

Up until the mid-1960s, opium buyers would lead strings of packhorses into Hmong villages to purchase opium, or the farmers would hike down to local markets and sell it there to these same highland merchants. But as the Communist guerrillas and the North Vietnamese forces began sweeping through these valleys, all transportation beneath the ridges was disrupted. Air America was the only way in and out of the Hmong villages. If they were going to market their opium, it was going to be on Air America. There was no alternative. And the opium trade was one of the pillars of economic survival for these people.

The use of Air America also increased the power of the Hmong warlords. Before the CIA’s aircraft would fly in to pick up opium, there had to be an authorization from the Secret Army’s commanders. And because of growing casualties as the secret war spread, rice production crashed. The villages were no longer self-sufficient in rice, so Air America would fly over and drop bags of rice. The delivery of relief rice into villages, and the transport of opium out of those villages, gave the Hmong warlords a stranglehold on the population.

As this war ground on, the tremendous casualties threatened the tribe with generational extinction of young males. In 1971 a U.S. Air Force report said that the oldest males in many Hmong families were down to ten years old.

Jensen: So why did the Hmong keep fighting for the CIA?

McCoy: Most didn’t want to. When I went into those villages to do my survey, it was at a particularly tense time, because the CIA’s Secret Army had put out a call for fourteen-year-olds. The village elders had gotten together and said, “No. We’ve lost everybody above this age, and if we start handing over the fourteen-year-olds, then the thirteen-year-olds and all the rest are going to follow, and who will marry the women and produce the next generation? We’re going to die. We can’t do this.”

When this village refused to send its young males to the slaughter, its rice was cut off. And they were hungry. That was actually the reason I was able to do my research: I made a deal with the village leader.

Now, this was a nonliterate person — not illiterate, but nonliterate, because the Hmong at that time had a largely oral culture. When I told him I wanted to know about opium, he said, “Can you get an article in a newspaper in Washington, D.C., saying that we gave our sons to fight in the CIA’s secret war, and part of the deal was that we would get rice?”

I said I knew a correspondent for the Washington Post. I couldn’t guarantee anything, but I would try.

He told me I could ask anybody I wanted to about the opium, and he’d send an escort with me, because there was a lot of guerrilla activity in the area.

So I talked to the people in his village, asking: How much opium do you produce? What do you do at harvest time? Where do you take it? How much do you get for it?

We later found out that a Hmong captain was radioing reports to the command of the CIA’s Secret Army about the questions we were asking. As we made our way to the next village to continue our survey, some soldiers in the CIA’s Secret Army ambushed us and tried to kill us.

When we got back to the Laotian capital of Vientiane, I went to see the head of the U.S. Agency for International Development [USAID], Charlie Mann, who had ambassadorial rank. I complained both that the CIA’s militia had tried to kill us, and that the rice, which was supposed to be humanitarian relief, had been cut off. Then I spoke to the Washington Post correspondent. Within days, a small article appeared in the back pages of the Washington Post. As that nonliterate Hmong leader had expected, Air America’s C-130 cargo planes bombarded his village with rice from USAID.

But that’s how that system operated: control over the opium and rice amplified the warlord’s power and allowed him to extract soldiers, in this case boy soldiers, for slaughter in the CIA’s secret war.

Jensen: What happened to all the opium? Where was it sold?

McCoy: Most of it was turned into heroin for sale to U.S. soldiers fighting in South Vietnam. The secret war in Laos introduced heroin-refining technology into the region. In 1969 and 1970, the CIA’s warlord allies built a complex of seven heroin refineries at the heart of the Golden Triangle, where Burma, Thailand, and Laos converge. Let me make this clear: all the laboratories were built by current or former covert allies of the United States. And they began producing high-grade heroin for shipment to South Vietnam. The local Asian addicts were opium smokers, which means the heroin was targeted purely at American troops. We know from a later White House survey that, by 1971, 34 percent of all U.S. combat forces in South Vietnam were using heroin. That means there were something like eighty thousand heroin addicts in the U.S. Army — more than there were in the entire U.S. — and all of them were supplied by our Southeast Asian allies.

Jensen: You’ve said that the CIA’s secret war in Laos had a broader legacy than just increased opium production.

McCoy: Yes, it changed the way we fight wars. Until the Laos operation, conventional military wisdom said that only infantry, the backbone of any battle, could take and hold ground. Air power, it was thought, could merely provide tactical support for infantry, destroying strategic targets that stood in the way of its advance. We couldn’t send troops into Laos, though, without violating our 1962 neutralization treaty with the Soviet Union. So we dropped 2.1 million tons of bombs on Laos — the largest, longest bombardment in military history. And we learned that if you bomb intensively and without restraint, you can actually use air power alone to take and hold ground. In the decades since Vietnam, we have used this strategy successfully in Bosnia, where we sent in very few combat forces, more successfully still in Kosovo, and most spectacularly in our recent war in Afghanistan.

The problem with this strategy is that it can produce serious violations of international law. When the international community witnessed our destructive use of air power in the Vietnam War, it became concerned about the enormous “collateral damage” the bombing caused. As the Vietnam War was winding down, the international community negotiated Protocol I of the Geneva Convention, which outlawed military attacks on civilians and on virtually all civilian infrastructure. The community of nations went even further and created the International Criminal Court to try those who violated these conventions. Although the United States was one of the prime movers in creating the Geneva Convention in 1949, President Reagan sent the treaty for Protocol I to the Senate with the recommendation that it be rejected, and it was.

In July 2002, the International Criminal Court opened at The Hague to try war crimes with the support of every major nation except the United States. We are proposing to lead this “new world order” governed by the rule of law. Yet because we’re wedded to an air-power strategy requiring bombing of both civilian and military targets, we are in conflict with the international law the rest of the world supports. As we move into the twenty-first century, these covert wars have left a very problematic legacy for the future conduct of U.S. foreign policy.

As we speak, there’s a big new crop of opium moving to market across Afghanistan. Since our intervention and the return of the warlords, opium production has soared from 180 tons to 3,400 tons. In 2002, Afghanistan earned about $1.2 billion from opium — more than from any other industry, and more than all its foreign aid combined. It’s going to be politically very embarrassing for the U.S. when our liberation of Afghanistan floods Europe with unprecedented quantities of heroin.

Jensen: Afghanistan is the most recent covert war, and the one most directly related to current events. How did it come about?

McCoy: In a very similar fashion to the war in Laos. Starting in 1979, the Carter administration — and later the Reagan White House — gave executive orders to the CIA to arm and supply the Afghan resistance to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. The only difference is that this was an international conflict, not just a U.S. operation. The Saudis, for example, heavily supported the Afghan rebels, as did the Egyptians.

Still, from 1979 to 1992 the CIA spent approximately $3 billion on this secret war, routing most of the money through Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence, or ISI. The result was a tenfold expansion of opium production inside Afghanistan, and growth in trade from localized opium distribution to large-scale heroin refining for the international market. In a by-now-familiar pattern, the tribal warlords inside Afghanistan were transformed into powerful drug lords.

After investing $3 billion in Afghanistan’s destruction, we spent nothing on its reconstruction when the CIA’s secret war ended in 1992. Washington simply walked away, leaving behind a wasted society. Afghanistan was our longest secret war, and in many ways the most severely devastated of our covert battlegrounds. The fighting left behind a million dead, 4.5 million refugees, and an estimated 10 million land mines — not to mention a ruined economy and a ravaged government. After the Soviets were defeated, the warlords we had created and armed began fighting among themselves for power, adding to the devastation.

As Afghanistan’s postwar problems multiplied, opium offered the simplest solution. In this devastated economy, there was astronomical unemployment, and opium is very labor-intensive; it takes nine times as much labor to harvest a hectare of opium as it does a hectare of wheat. So opium harvesting put people to work. Opium also commands a high international price, which meant the impoverished farmers could earn hard currency to finance the rehabilitation of their farms and communities. Another obstacle to Afghanistan’s postwar reconstruction was that international agricultural commodities are traded through a very complex diplomacy. Without a functioning government, Afghanistan didn’t have the capacity for such diplomacy. As an illicit commodity, however, opium could easily pass across every border in the world. And then there were the periodic droughts in that parched land at the northern extremity of the monsoon rains. Opium uses about half the water of food crops. So from every perspective, opium was the ideal solution to Afghanistan’s postwar problems.

Under conditions of civil war in Afghanistan, from 1992 to 1996, opium production continued to climb upward. When the Taliban took power in Kabul in 1996, only three countries in the world recognized the new government, and Afghanistan remained isolated from the international economy. The Taliban quickly realized what the warlords they’d superceded had always known: that the only way to operate a state economy “off the grid” was through narcotics. So they not only continued to tolerate the drug traffic; they imposed a rough order that increased the commerce and made it more efficient. Opium production inside Afghanistan doubled. Most importantly, the Taliban allowed the heroin processors to move across the border from Pakistan. By 1999, they were producing an extraordinary 4,600 tons of opium a year — enough to supply 75 percent of the world’s heroin users.

Afghanistan had become the first nation in history whose economy was built predominantly upon opium. The drug trade accounted for most government revenue and all foreign exchange. It also absorbed most of the country’s merchant capital and much of its water and prime arable land. And, above all, opium provided seasonal employment for about 25 percent of the adult males, which means 25 percent of the workforce, because under the Taliban, women couldn’t work.

By 2000, though, the Taliban had become desperate for international recognition. Throughout their brief rule, they had more or less offered the UN a deal, saying indirectly, “We’ll eradicate opium if you’ll give us diplomatic recognition.” Then, in July 2000, the Taliban issued an opium ban and, with characteristic ruthlessness, eradicated 99 percent of the opium crop in their territory, which was most of the country. Afghanistan’s opium production crashed from 4,600 tons to around 180 tons. The Taliban then sent a delegation to the UN, accusing the Northern Alliance, which still held an enclave in the northeast, of being drug lords, heroin traffickers, and thugs and saying, “We’ve eradicated opium. Give us diplomatic recognition.” The UN refused.

So when the U.S. invaded Afghanistan after September 11, 2001, we were invading a country that had been through a decade of covert war, then a decade of civil war, and finally an act of economic suicide. By the time we attacked, there was nothing left except the Taliban’s rather weak, badly led army of forty thousand men. Refugees had been flowing out of Afghanistan for more than a year, not just because of drought, but because the Taliban had destroyed the country’s largest source of employment and only export. Once we invaded, this army without a society to support it quickly collapsed.

When planning the Afghan War, the United States realized that the only allies we had were the Northern Alliance and the Pashtun warlords in the southeast — the same warlords we had armed back in the 1980s, and who had, in the 1990s, operated pretty much as independent drug lords. The Northern Alliance controlled the one territory inside Afghanistan that hadn’t banned drugs, and they were still very large opium producers and heroin smugglers. More important, they had huge stockpiles of opium left over from the 1999 bumper crop, which the world market simply hadn’t been able to absorb: about 60 percent of the opium had been held back after the harvest. The Northern Alliance now transformed much of that opium into heroin and smuggled it into Europe and Russia.

These are the forces with which the U.S. mobilized to fight the Taliban, and the warlords we have since installed as rulers of rural Afghanistan, the vast countryside around Kabul. In the weeks after 9/11, the CIA, on President Bush’s orders, sent veteran operatives into the Northern Alliance–controlled zone armed with bundles of hundred-dollar bills to buy warlords. By the end of the Afghan War in December 2001, the CIA had spent $70 million in cash, and the opium warlords were back in control of the countryside. The wisdom of that decision has proven dubious, even militarily speaking. During the bungled Tora Bora operation, when it looked as if the U.S. had Osama bin Laden and most of al-Qaeda cornered in caves, one of those warlords, Hazarat Ali, controlled the territory between the caves and the Pakistani border. With a mercenary’s eye for business, he sold al-Qaeda “Get Out of Afghanistan Alive” cards — for a bargain price of about five thousand dollars a head.

As we speak, there’s a big new crop of opium moving to market across Afghanistan. Since our intervention and the return of the warlords, opium production has soared from 180 tons to 3,400 tons. In 2002, Afghanistan earned about $1.2 billion from opium — more than from any other industry, and more than all its foreign aid combined. It’s going to be politically very embarrassing for the U.S. when our liberation of Afghanistan floods Europe with unprecedented quantities of heroin.

Each time we bring the blunt baton of law enforcement down upon this illicit global market, we create an increase in price, which in turn stimulates production and geographical proliferation. Intervention at the level of trafficking only forces drug lords to create ever-more-complex smuggling networks. The net result of America’s five drug wars has been a fivefold increase in global opium production — from 1,200 tons in 1970 to 6,100 tons 1999.

Jensen: How does all of this relate to the drug war in the United States?

McCoy: Since 1971, under President Nixon, we’ve spent approximately $150 billion to fight five drug wars. That’s not quite half the cost of the Vietnam War. And that doesn’t include state and local costs for prosecution and incarceration. The cost of building and operating prisons for nonviolent drug offenders is enormous.

Since the mid 1980s, this expanded drug war has been fought at home primarily with longer jail sentences. It has created an enormous prison population and done incredible damage to racial harmony in this society. From 1930 to 1980, American society had, on average, a hundred prisoners per hundred thousand people. After President Reagan’s drug war started in the 1980s, the incarceration rate grew within a decade to four hundred per hundred thousand. Now, twenty years later, we are well above seven hundred prisoners per hundred thousand.

The Sentencing Project, a nonprofit organization, has found that about a third of African American males between the ages of eighteen and thirty are either on parole, in prison, or under indictment. And the lion’s share of them are incarcerated for possession or petty sale of narcotics. When these African American men emerge from prison, they’re stripped of their civil rights. In many states, they can’t vote. This represents the criminalization and the political disenfranchisement of an entire community. Unless we turn it off, this doomsday machine will keep sweeping the streets for drug users, packing the prisons, and adding to these enormous social costs.

Jensen: I’m not as familiar with Nixon’s drug war. How was it fought?

McCoy: From the late 1940s to the early 1970s, the infamous “French Connection” was the source of about 80 percent of America’s heroin supply. Here’s how it worked: Turkey had farmers producing opium to sell to licensed pharmaceutical companies for use in making legal medical morphine. These farmers routinely produced more than their quota, shipping their bootleg opium down to Lebanon, where it was refined into morphine and shipped to France. There, the Corsican syndicates, protected by French intelligence and the Gaullist government, operated a complex of clandestine labs that transformed the morphine into heroin. They shipped it to Montreal, Canada, where the Cotroni Mafia family smuggled it down to New York for distribution across the Eastern Seaboard.

Because the farmers in Turkey were all licensed for legal pharmaceutical production, the Turkish government knew who they were. In 1972, at Nixon’s insistence, the Turks simply eradicated opium farming. The U.S. provided around $30 million to help the farmers make the transition to other crops. Then we leaned on the French, who of course knew exactly who the traffickers were, because they all belonged to a paramilitary organization called the Civic Action Service that actually provided state security for the Gaullist regime. The French police closed down the heroin labs, and after twenty years of smooth operations, the French Connection was destroyed in a matter of months. Nixon had scored a total victory in the first of America’s five drug wars.

But every victory in the drug war is just a down payment on a later defeat. Demand for heroin was still high, and there was now a shortfall in supply. So the international price went up, creating a strong incentive for a boom in production in Southeast Asia. To add to this response, the Vietnam War was over, the last of the GIs were gone, and Southeast Asia’s opium producers had a surplus. Suddenly the U.S. began getting large shipments of heroin from Southeast Asia.

So Nixon fought and won a second battle in his drug war. In 1973, he sent thirty DEA agents to Bangkok, where they did a very effective job of seizing heroin bound for the United States, thus imposing an informal customs duty on Thailand’s heroin exports. The Southeast Asian traffickers simply turned around and exported to Europe, which had been virtually drug-free for decades. You see, the French syndicates had an agreement with the Gaullist government: they could manufacture heroin, but they couldn’t sell it in France. With the French Connection now out of the picture, the Southeast Asian syndicates were free to flood Europe with heroin. By the end of the 1970s, Europe had more heroin addicts than the United States.

Each time we bring the blunt baton of law enforcement down upon this illicit global market, we create an increase in price, which in turn stimulates production and geographical proliferation. Intervention at the level of trafficking only forces drug lords to create ever-more-complex smuggling networks. The net result of America’s five drug wars has been a fivefold increase in global opium production — from 1,200 tons in 1970 to 6,100 tons 1999.

It’s the same with cocaine in South America. In the fifteen years we’ve been fighting a drug war in the Andes, cocaine production in the region has doubled. During the 1990s, the pursuit of the drug war in Peru brought the CIA into alliance with Vladimiro Montesinos, the head of state security under the Fujimori dictatorship. Today he is in prison for corruption, and his overseas bank accounts hold a quarter of a billion dollars in drug money. He single-handedly corrupted Peruvian democracy. With perfect symmetry, for each hectare of coca that we destroyed in Peru, another one was planted in Colombia. While Peru’s crop dropped from 120,000 hectares to 38,000, Colombia’s rose from 37,000 hectares to 122,000. Now we’re applying pressure on Colombia, and Peruvian production is coming back up. And of course our covert involvement in the politics of these nations damages our relations with them over the long term.

The UN has the idea, and the United States as well, that because narcotics production is concentrated in a few limited areas, we can make a knockout blow and end this drug problem once and for all. The U.S. favors “aerial defoliation.” The UN favors crop substitution. But both share a belief that they can, after nearly a century of effort, finally eradicate the narcotics trade. And it’s possible, in theory — and sometimes in reality — to apply enough coercive force to extirpate an illegal commodity from a particular locality. But as we’ve seen, in an age of illicit global commodities and transnational organized crime, the traffic, when subject to such pressure, just slips sideways into other areas, into a virtual infinity.

Let’s just assume, however, that the U.S. and UN were somehow able to succeed. Let us imagine that, in this new world order, the prohibition regime is finally able to eliminate opium and coca production.

This takes us back to Nixon’s second victory. When we disrupted the flow of heroin from Southeast Asia to America, Mexican syndicates began producing large quantities of heroin and cannabis for shipment to the United States. In 1975, the Ford administration began a massive drug-eradication effort in Mexico and sealed the border. The result was that much of the marijuana production shifted south to Colombia, laying the economic foundation for the drug cartels that later switched to cocaine production. But, most importantly, as the heroin supply dried up, U.S. distribution syndicates turned to synthetics, particularly amphetamines, making Philadelphia the “speed capital of the world” by the late 1970s.

If the 1980s were the boom decade for cocaine, then the 1990s witnessed a spectacular growth in the global traffic in amphetamine or amphetamine-type substances [ATS]. Currently, there are about 14 million opiate abusers in the world, and about the same number of cocaine abusers. There are 30 million ATS abusers. It’s as big as opium and cocaine combined. One of the important aspects of ATS is that the labs are sited close to consumer areas, so interdiction is essentially impossible. The point is clear: if the UN and U.S. manage to eradicate natural narcotics — opium and coca — then the illicit economy could quickly replace them with a limitless supply of synthetics.

We’ve gone from the simple, straight-line network of the French Connection to an infinitely complex cat’s cradle of global trafficking routes that resists intervention. The drug war isn’t simply failing; it’s counterproductive. Prohibition stimulates production. Any economist could tell you that. If you told the Federal Reserve bankers that adjusting interest rates has no impact on the American economy, they would laugh. That’s the point of adjusting interest rates. That’s the point of market intervention. Yet all these law-enforcement agencies — from the DEA to state police — think they can intervene in the illicit drug market without affecting the traffic. There is no “immaculate intervention.” Intervention, particularly unwitting intervention, only makes the problem worse.

Jensen: Where does all of this leave us concerning the war on drugs?

McCoy: I think prohibition is going to be substantially revised in the years to come, though not completely discarded. Legalization isn’t politically possible in the short term — or even the medium term — given that prohibition is embedded in so many state and federal laws, not to mention international treaties. There’s no political will to unravel all of that at this point.

The debate has now moved from prohibition to pragmatics. We’re no longer talking about whether drugs are moral or immoral. Instead, we’re starting to ask: What works? What are the costs? Drugs may be illegal, but incarceration is not a rational way to treat drug abuse. We are moving, albeit very slowly, from prohibition to decriminalization — which is not the same as legalization. We’ll hear more states every month saying, “Let’s give people treatment.” California passed Proposition 36, mandating treatment, not prison; Michigan is repealing its mandatory-minimum sentences; and even New York is debating the end of the so-called Rockefeller drug laws that started the whole trend toward heavy sentencing for drug offenders back in 1973. I think there will be a shift toward minimizing the damage, both from drugs and from law enforcement. Within ten years, I expect we’ll see no incarceration for personal possession. Part of the reason is that we can move from mass incarceration to mass treatment without changing state, national, and international drug laws. All we have to do is change their sentencing provisions.

The boom economy of the 1990s is over. We’re beyond the dot-com age. Money is now real, and fiscal choices are severe. Faced with a choice between mass incarceration or better education, which will most people choose? What about a choice between more prisons for nonviolent drug offenders or prescription-drug benefits for senior citizens? If it comes down to a new prison for their neighbors’ children or medical care for their parents, the decision for most U.S. voters is pretty obvious. I think economic reality is going to force us to ask whether this drug war is working. With state after state requiring treatment instead of jail terms for first-time drug offenders, we are winding down the drug war. Meanwhile, many European cities have adopted the “Frankfurt Resolution,” urging an end to prison sentences for first-time drug offenders and the decriminalization of all drug use. The same kind of global mass movement that built the prohibition regime nearly a hundred years ago is now starting to tear it down.