I am a bath mystic. You can also be one. Read this and decide if bath mysticism intrigues you.

First, you need a bathtub. I recommend one with lion’s-claw legs, or eagle’s-claw. Old bathtubs are best. The more baths taken in a bathtub, the deeper and prouder its “bath memory.” New bathtubs are mostly inhospitable to bathing. They are composed of plastic, and the sides are uncomfortable to lean against. Today’s bathtubs are built to stand in while showering.

America is the hardest-working industrial nation. We make the Germans look like a nation of hobos. Inhabitants of the U.S.A. awaken early, drink a cup of coffee, work all day, then return home and mow their lawns.

Americans prefer showers because showering is a kind of job — you stand, you scrub, you shampoo. In comparison, bathing is inactive. You lie in a bathtub, your eyes closed. You accomplish nothing. By the end of a long bath, you’re slightly older and slightly cleaner.

So undervalued are baths in our culture that there is no word for “taking a bath,” as there is for showering. (The word bathing covers all types of personal cleansing.) For this reason, I suggest the word bathifying, which conveys some of the leisurely thoughtfulness of the bathtub. Bathifying resembles edifying, meaning “tending to educate or uplift.” For the remainder of this essay, I will use bathifying and its noun form, bathification.

As I say, you need a bathtub. Or you could use a large canvas bag, filled with water.

Another necessity is soap. Soap is an infinitesimal part of bathing, but nevertheless a part. Over my years of bath mysticism, I have used hippie oatmeal soap, brown Egyptian soap, and nostalgic and thrifty Ivory. At the moment I use Dr. Bronner’s almond soap, diluted nine to one. It foams, but does not sting.

Warmth is key to bathifying. True, there are cold baths — particularly in summer — but a cold bath, like a cold soup, is never humanely satisfying. In fact, a bath is a kind of soup in which one’s body is the main ingredient.

It would be possible actually to bathe in soup — surrounded by chunks of parsley and potato. This would benefit the skin and pores, probably, but the sight might strike observers as mirthful.

Although some might compare the warm water of the tub to amniotic fluid, I don’t believe we bathifiers are seeking the womb. Instead, we are seeking a home. A bathtub is the smallest home, combining several of the necessities of a house: a bed, a hearth, a sink. The only thing missing is a roof. (Some might even say the tub acts as toilet — for certain persons, let us admit, pee in the tub. I personally do not follow this practice, although I feel this is a question each bathifier must decide for him- or herself.)

While in the tub, I remember my dreams — but not in exact detail. I recall the sensations experienced in the dreams: the feeling that dinner is almost ready; the sense of meeting a new person I don’t completely trust. In water, a medium wherein most substances dissolve, exact truths dissolve, too. Only near-truths remain — with almost the same intensity as they had in sleep. The bath world and the dream world have similar agendas.

Even fingerprints change in a bathtub. They soften.

You may allow your hand to rest on your genitals as you bathe. I pursue the Middle Path with regard to masturbation: I neither truly masturbate nor refrain from self-touching.

One must take a bath naked, without social decoration. You remove your army helmet, your beatnik beret, your businessman’s necktie, your Slovakian suspenders. Like a Buddhist monk with a shaven head, you are shorn of your societal meaning. No longer a “Chaucer scholar” or a “diesel mechanic,” you’re a big six-foot-one person with brown skin, or a girl with freckles. You repose, looking down at your own legs and lower abdomen, which you hide from your priest and your landlord. What is the big secret you are withholding from scrutiny? Here it is, bulging slightly in relaxation, the opposite of a mystery, open to your own ambivalent scrutiny.

I am beautiful, you think. Then, I am fat.

April 4

I was in Manhattan for two nights and had no time to bathe. Now, back in Phoenicia, I am bathifying for the first time in three days, and my skin and nerves recall the exact pleasure of warm — or even hot — water. You can forget this experience, like forgetting how it feels to be in Hebrew school.

April 15

My wife and I once bathed in an outdoor bathtub in Scotland. We heated water on a wood stove, poured it in the tub, and waited until it was cool enough to descend into. Above us, the sky grew crowded with hundreds of Scottish stars. How silent and aware is the Scottish night sky!

April 22

I bring down the rubber ducky (who lives on the rim of the tub) to share my bath. Immediately, the duck falls over on its side, gazing up at me with its penetrating black eyes, as if asking for my help.

But I do not help. I allow this creature to float pathetically. How tedious are rubber ducks!

April 23

In the bathtub tonight, I have this sudden tactile sensation: I feel as if I am wearing a silk gown. The soft, yielding water rubs me something like silk. For me, a man who never wears a dress, a bath is the one place to feel silk-clad.

May 19

I often ponder some mystery while bathifying. Today I considered the concept of a miss. What is a miss? If you throw a rock at a tree, there are two possible outcomes: hit or miss. Striking the tree is a hit; everything else is a miss. By this definition, all of the world that is not the tree — the nation of China, all automobiles, the Pacific Ocean, Cher — are united within the category of “miss.”

This inclusivity of “miss” is the inverse of the exclusive “hit.” How vast is “miss”! Almost as large as God! “Miss” is everything, minus a single tree.

May 20

Bathtubs do not exist in nature. Showers do. The word shower may refer to a rainstorm. A waterfall is also a shower of sorts. But nature does not create a body of water the shape of a person, the same way nature does not create clothes.

May 24

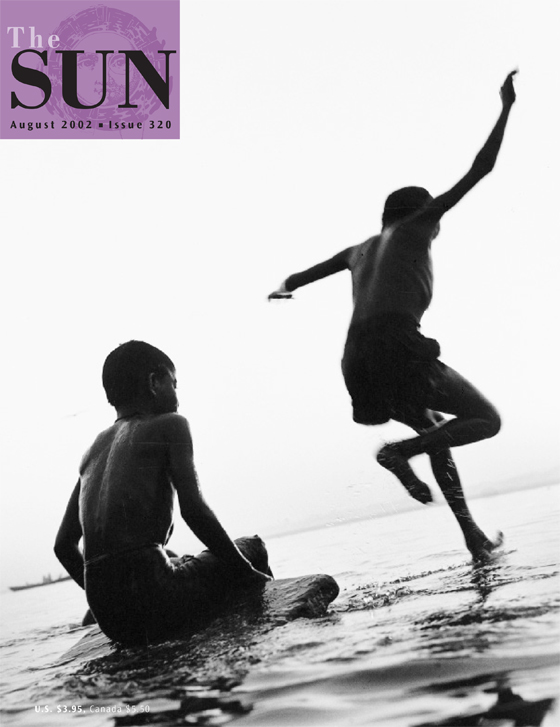

My daughter Sylvia rarely bathes, but red itchy welts have appeared on her back, so I am giving her baths daily. I can see she is learning the bathifying art. At first she had an anxious “what should I do?” look. But she has begun to lie back and float. (Because of her small size, she can actually float in a bathtub.) And later, when she emerges, she is purposeful and sparkling with limb-intelligence.

Today Sylvia complained of a pocket of cold water in her bath: “It’s cold right here!”

Why don’t I have pockets of cold in my bath? I wondered. Later, when I took my bath, I noticed that I hunch my shoulders forward occasionally, sending small waves forward and back. A gentle stirring occurs. I mix my tub’s water, unconsciously! There is more activity to bathifying than I thought.

June 13

Is it possible to pray in a bathtub?

No. In a tub one cannot be pious. One may remember a joke, but one cannot pray.

(All right, maybe a saint can pray in a bathtub.)

June 18

The bathtub is good for remembering the names of old girlfriends. I once slept with a girl named Julie. (At the time she was a girl — perhaps seventeen.) We had no birth control, so I had to ejaculate outside of her. Actually, she didn’t care where I ejaculated.

In fact, there is a small chance that she became pregnant. A twenty-six-year-old man who is my son could be walking down a sidewalk somewhere in Florida.

Or was her name Chris?

July 2

Without the plug (or some such stopper in the drain) there can be no bath, and thus no bathifying. But what does the plug represent, philosophically?

The plug is the ego. Water does not distinguish itself into separate entities. All of the world’s water could merge together into one vast ocean. But a bath is separate. A bath is one tiny pool of water, alone and warm. A bath is an individual, like the person inside it.

Lift up the plug and the water escapes, ultimately to mix with every other body of water on earth. Perhaps when we die, a plug is pulled, and the life within us mixes with all life.

July 3

I never noticed before the buoyant qualities of my limbs. My arms float slightly in the tub. For some reason, I was not previously conscious of this. The rest of my body doesn’t obviously float, but I think there is a slight upward lift, particularly on my back.

The sense of being lifted up is a hopeful one — buoyant can also mean “happy.” Possibly the secret joy of bathifying is its assurance that “something is lifting me up.” It is a kind of faith made tangible.