IT WAS HOT and I wanted to die, in a way. I was tired of being twenty-five years old and festering as an undergraduate at one of the largest cow colleges in the deep South.

It was also humid, and I’ve always abhorred humidity, even though I was born and raised as far south as you can go, unless you count Florida, but I’ve never counted Florida in anything at all. I’ve never been to Florida and have no plans to go there of my own free will. There are many places that, for biased and perhaps ignorant reasons, I don’t ever want to go. Just off the top of my head: Dallas, Atlanta, Houston, Boulder, Denver, Phoenix — especially Phoenix — all of Alabama and West Virginia, and any part of southern California. Most of the eastern seaboard I’d like to see, but I’ll probably never get past the Mason-Dixon line.

So it was hot and humid, and I was thinking how terrible it was to be alive on such a night and in such a place as Baton Rouge, Louisiana. I’d been in college for five years, since 1990, and it was beginning to rot me. I probably wouldn’t have gone to college at all if I hadn’t lost my left arm in a car wreck when I was nineteen years old. Before the accident, all I’d known about college was that it was where the ugly and unpopular people in high school went after graduation. Where I went to school, the cool and good-looking people didn’t go to college. They all went to work, or died young, or started heavy-metal bands. I’d formed a band myself in my senior year of high school, a speed-metal group called “Damascus Steel.” I had no idea that there was a real place named Damascus. I just liked the way it sounded. I had every intention of becoming famous with this band, and every intention of dying as young as possible. I failed at both, though narrowly on the second, as I did die in the car accident, but the cocksuckers brought me back to life four times, which must be some kind of record. I still have every intention of becoming famous someday, even if it means shooting someone famous or blowing up a building.

So I was a twenty-five-year-old, one-armed undergraduate. Since I couldn’t play the guitar anymore, and I needed some way of expressing myself, I’d decided to study writing in college. But who except a genius can write anything worth reading at the age of twenty-five? And I most certainly was no genius, though I had excellent taste in books. The real geniuses in my classes were frightened of me. They couldn’t quite get their minds around this cripple who read good books. They’d never seen anything quite like me before.

That hot night, I’d just finished writing a story about Simone de Beauvoir. This story was so bizarre that it had even turned me off with its strangeness. So I left my room and did what I always did when I couldn’t write or was writing badly: I walked — ten, fifteen, twenty miles in a night. I might have been one-armed, but my legs were two pieces of solid muscle from all that walking, from not having enough money to do anything but walk.

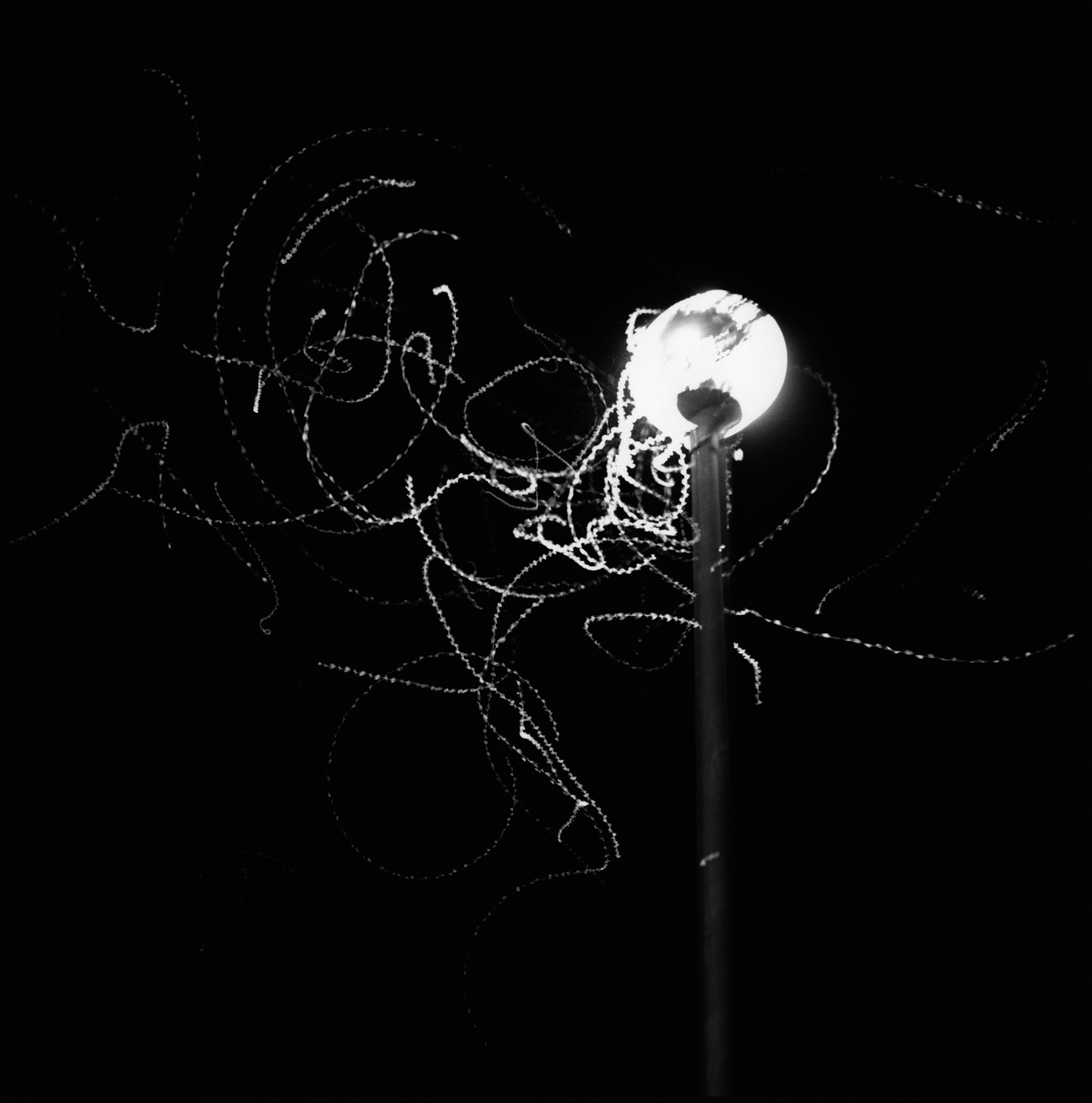

By some accident of fate, or perhaps because I was simply curious or bored, I found myself sitting on the diving board of the world’s largest swimming pool. The pool had been built during the Great Depression by Governor Huey Long in an attempt to boost Louisiana’s morale. Long had pumped a shitload of money into LSU, which was at that time a true third-rate college. On this particular night I wanted to kill myself because I was twenty-five and one-armed and awkwardly sitting over the water at the world’s largest swimming pool.

I got up to leave, and for some reason, perhaps the effects of the July heat on my brain, I intentionally left my gold-rimmed glasses on the diving board of the world’s largest swimming pool. I’m not sure what message I was trying to send myself by leaving my glasses there, but that’s what I did. This was a pretty big deal, because those glasses were expensive bifocals, specially designed for my idiosyncratic eyes: one eye is larger than the other and is going bad twice as quickly. If not for my mother’s good graces, I wouldn’t have had those glasses at all, and without them it was all but impossible for me to read or write. Perhaps this was the reason I left them.

This is terrible, I know. But it gets much worse.

I left my glasses at the world’s largest swimming pool and walked to the university’s bell tower and stood with my back against its cold granite for at least half an hour. Something was happening to me. I thought perhaps it was what Samuel Beckett called “blood fatigue.” At least, that’s how it felt. Perhaps it was my toxic atheism catching up with me as I stood against the bell tower waiting for a sign — something, anything. Did you know that bell towers were invented in the Middle Ages to tell everyone in town when it was time to pray? The chimes now seemed to serve no particular purpose, unless you regard getting to class on time as a kind of religion. Our contemporary age has no meaning whatsoever. We attempt to hold back meaninglessness by working nonstop and immersing ourselves in any amusements we can get our hands on, because to be moral is too much work. We are ashamed of having killed God, or all gods.

Earlier that day I’d sat on the lower steps of the bell tower. The steps lead to a door, behind which is a staircase that goes to the top of the tower, where the chimes are. The door is protected with complicated locks for fear a sniper will climb the tower and shoot people, as happened many years ago in Austin, Texas. I was smoking cigarette after cigarette, waiting for my philosophy class on Kierkegaard to begin at noon and feeling arrogant because I had no equals in that class. Not even the professor himself could keep up with me, so well versed was I in Kierkegaard. I was also angry, so angry I could have lashed out physically at anyone who had the nerve to come up to me to chat or even ask for a light. Fortunately for myself and my potential victim, I knew hardly anyone, so it wasn’t likely that anyone would approach me. But if someone had, it would have been the death of them. My thoughts were often murderous back then — partly, I suppose, because I was one of the few working-class students on campus (or so it seemed to me), and also because all the books I was reading were imbued with violence and were anti-everything save absolute individuality: the self as the only thing that can truly be known.

That morning there were two black female janitors sweeping around the steps of the bell tower, where I sat chain-smoking and thinking of Kierkegaard’s notion that “the truth is the greatest tension possible for an existing individual in time.” The janitors annoyed me with their incessant chatter and the wisp-wisp of their obnoxious brooms. Their instincts must have told them I was not to be greeted with a “Hello” or a “How are you?” Or perhaps it was the missing arm that told them so. One of them stopped and said to the other, not too softly, “We may be sweeping his cigarettes, but at least we have a God.” I pretended not to hear them, though inside I was boiling, because she was right. And I was stunned that she had said this at that moment, because the thought had just crossed my mind: They may be janitors, but they’re probably a lot happier than I am, with their illusions of God fully intact.

Now, at midnight, the bells rang out twelve times, and I stood, soaking up their vibrations. I have always loved the sound of bells reverberating through the air. I think bell towers should be offered blood sacrifices twice a day: once at sunrise and once at twilight. Our contemporary humanity has destroyed us. One day the world will blow up, because the earth demands blood sacrifices, and we have turned up our noses at such primitivism.

When the midnight bells stopped ringing, I lit another cigarette and headed to the barrooms along Chimes Street. I’d been told that the poet Robert Lowell had once lived on Chimes Street, but because Lowell wasn’t Ezra Pound or T.S. Eliot, I wasn’t all that interested in this bit of trivia. That LSU had been the headquarters for a major literary movement, the Agrarians, didn’t mean much to me, either. Too full of nature and tradition for my taste. I hated nature because I was influenced by that enfant terrible Jean-Paul Sartre. Cities were the best places to waste one’s pointless life. Admittedly, Baton Rouge wasn’t much of a city, but it was all I had to work with at the time.

SOMEHOW, someone, somewhere had given me a credit card. This was unfathomable to me: I, who had nothing, had been issued a card with enough credit to buy a mid-size car. I went into one of the bars on Chimes Street and used it to buy a cheap vodka and an even cheaper beer. They served the beer in a styrofoam cup, which pleased me immensely for some reason. I sat at one of the formica-topped tables, pulled out my notebook, and filled up a page with nonsense until my hand hurt. I kept getting up and stuffing the jukebox with quarters, playing the same song over and over: “When the Shit Hits the Fan,” by the Circle Jerks. By the time the barkeep told me to stop, I’d wasted three dollars, money I’d gotten from selling some of my philosophy books earlier that day: Why I Am Not a Christian, by Bertrand Russell; Irrational Man, by William Barrett; Creator and Creation, by Miguel de Unamuno; and The Complete Works of Aristotle. I would not have parted with my ragged copies of Sartre’s Being and Nothingness and Albert Camus’s The Rebel even if it meant dying of extreme hunger.

After my third Styrofoam cup of beer and fifth shot of the worst vodka in existence, I wrote in my notebook: “I am a cripple, therefore I rebel.” Some actresses from the Baton Rouge Alternative Theatre walked into the bar. They’d just finished an all-female production of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. I’d seen the play twice during its six-week run and was obsessed with the actress who played Estragon. I wondered if they knew that Beckett would have been appalled by an all-woman performance of Godot. He would not stand for any alterations of his plays, and if he hadn’t been dead, he likely would have sued the theater company. The actress who played Estragon had also played Inez, the supposed lesbian in Sartre’s No Exit. I like lesbians on instinct and would certainly be a homosexual myself if not for the fact that I loathe both sexes equally. But this woman got the best of me despite myself. I wouldn’t dare go up and talk to her. In those days I wouldn’t dare go up and talk to anyone at all, save the most wretched person I could find. So I sent the actress a note instead, written on a bar napkin in my best handwriting. I had to squint, and it’s hard to write on a bar napkin anyway if you have only one hand, unless you find just the right object to hold the napkin down, and even then it’s difficult, because bar napkins have a tendency to rip. Why didn’t I use paper from my notebook? I thought it would be more seductive to use the napkin. Ridiculous, you say? You are right; it is ridiculous, because I am a ridiculous person. Here is what I remember writing to the actress:

I admire your acting. You seem full of death. I’m full of death too. We should talk. You wouldn’t come over for a chat, would you, and a drink, would you?

One of the actress’s friends walked up to the jukebox and began pushing quarters into the slot. I gave the note to her and asked her to give it to “Estragon.” She said she would, and I put my notebook in my bag and left. Apparently I didn’t want to talk to the actress after all. Maybe I just wanted to find out if I had the courage to send her a note. The actress filled me with passions, and I wanted to be empty of all feelings, so I’d written the note to be rid of my obsession, to be rid of her. Also, in those days, it was important for me to reject people before they rejected me. I truly detested everyone who came into my presence. I could get along only with the dead, and then only if they had written books I could admire, books I could fall before as if they were gods. This hasn’t changed much through the years. Even now I have few friends, most of whom I never asked for, some of whom make me want to rush home and put a bullet through my head every time I get entangled in a conversation with them. I believe one should speak no more than is necessary to get by in life, except on the page, and even then one should be cautious about saying too much.

I am a boorish asshole. Such is my destiny.

When I walked out of the bar, the hot summer air worsened my already bad mood. The humidity was so thick I felt as if I were being plastered with creosote, and as I walked down the crowded street, all I could think about was my expensive eyeglasses that I’d left on the diving board of the world’s largest swimming pool. It made me sick: how could I have done such a thing? I prized those glasses almost as much as I did my complete paperback collection of Kierkegaard.

Although I despised Kierkegaard’s Christianity, I admired his energy and the tension in his writing, like two stones rubbed together to make sparks. I appreciated how he denigrates the Christian church, rendering it absurd, like a mouse driving a crane or a dog reading Jaspers’s early work. For Kierkegaard’s belief in Christ is irrational. I can almost admire Jesus for putting on such a spectacle, but I cannot admire the millions upon millions who believe that he conquered death. At most he conquered himself, and even that was secondhand, considering that he truly believed his Father in heaven would save him at the last moment. That’s called “cheating” where I come from. But his God did not save him. All gods are evil, and the man who died on the cross, whom we call “Christ,” was just a man, nothing more and nothing less. Such is my opinion even today.

As I walked through the crowds on Chimes Street, passersby took quick glances at my empty sleeve, my not-arm. To give them the benefit of the doubt, perhaps their eyes were drawn by my extra-large, multicolored polyester shirt. I wore oversized shirts to hide the contours of my stump. Sometimes this worked, and sometimes it didn’t. The shirt I wore that night had all the colors of the American flag on it, and also orange and yellow stripes. Funny that I should mention the flag in relation to my shirt, for I hardly think about America at all. Why should I? Why should I think of anything other than my own death? Somewhere along the way I read that death is the only thing worth thinking about, and this notion settled deep into my blood. Truly, death and amputation are all that concern me every second of my miserable life.

I’LL CONTINUE down this path of suffering we call the “story line,” but it won’t be pretty or nice or anything they ever tried to teach me in school about writing. What could be more ridiculous than teaching someone how to write? If, like everyone, I’m only going to die in the end, what’s the point in taking any kind of advice or instruction? The sooner you realize that no one can help you through your narrative — that is, through your life — the better off you’ll be, for at least you won’t have unrealistic expectations screwing up your thinking, and you can become one with your nothingness. In this way, you’ll be free — free to follow your own impulses and desires, which will take you as far as you can go in life, as well as in writing.

How I loathe teachers and priests. Especially teachers.

I walked to the end of Chimes Street and did something I’d never done before: I sat down in the middle of the bums who were lined up along the front of the blood bank. They were black, white, Latino, and Native American: a wall of multihued flesh. Some were drinking beer or whiskey; others were taking quick hits from their crack pipes or smoking cheap weed. Their eyes turned on me as I took my place among them.

I sat next to a mustard-eyed black man who mumbled something to me — I had no desire to figure out what he was trying to say — then passed me a bottle of cheap wine. Before long I was drunk and hurling insults at the passersby. The bums pleaded with me to stop, but it is not like me to listen to anyone’s good advice. I hollered out terrible things until I insulted the pretty girlfriend of a young redneck, who started punching me hard in the face. The beating didn’t hurt at all. In fact, it felt delightful: actual physical sensation! It had been a long time since I’d felt anything. But I was getting worried he might knock my eye out of its socket, so I stood up and revealed my crippled condition to him, which had no effect. He said he didn’t care if I was one-armed; he was going to beat the shit out of me anyway. And he did. None of the bums came to my rescue. Why should they have? I was a stranger.

After the beating, as I leaned against the blood bank’s door, the black guy who had passed me the bottle spoke clearly: “I told you to stop saying all that shit about there being no God to them people.” If only he’d known how much I liked getting beaten up, perhaps he would have kept his mouth shut.

A few of the bums gathered around and helped me to my feet, not that I needed any help: my legs were fine. But my face was hardly discernible as a face. My features felt as if they’d merged into a solid mass of misery, and the blood poured and poured. Certainly my nose was broken. But I’d been beaten worse before. I told the bums I’d buy them a case of beer if they’d hang out with me for the rest of the night. They agreed. What bum worthy of the name wouldn’t agree to free alcohol?

We walked across the street to the 7-Eleven, where I bought beer with the credit card that someone had been foolish enough to give me, and we all went behind the store to drink it. The bums started telling stories, which were somehow comforting, even though they weren’t all that good. I guess that’s why people tell stories: to comfort one another. There was this one bum who claimed he’d ended up on the streets because he’d stabbed a man to death in Texas and had been forced to flee his home forever. He promised not to kill me if I passed him another Budweiser. Ha-ha. I passed him a beer. I thought he was a liar. A true murderer would never have confessed his crime to anyone, for any reason. Or was it just the opposite?

Another bum was known as George the Highlander, because he did his bumming on Highland Boulevard. He was grayish and fat, and his face was burnt red. He fished a crumpled newspaper clipping from his back pocket. It was a front-page photo in the university paper of George reclining peacefully on the shore of one of the university’s lakes. The caption read: “George the Highlander takes a noonday nap.” There were ducks and geese in the background: a serene, utopian scene. George said he’d moved to Baton Rouge after he’d been doused with lighter fluid and set afire in Atlanta, Georgia, by a group of spike-haired punks. He showed me his scars, which were nothing compared to mine, but I didn’t show him my scars. They’re mine, and I’m not a generous person.

When the conversation turned to me, the bums asked the question everyone eventually ends up asking: “What happened to your arm?” I told them I’d lost it when I was in the army during Desert Storm back in ’91. It felt good to lie. I’d been wanting to lie to someone about how I’d lost my arm for some time. I could tell that none of the bums believed me, but none of them called me on it either. I was growing bored and angry. These bums were not mean enough for me. I liked them, but only up to a point. I’d rather have been in my dorm room reading Nietzsche. For no reason at all, I raised my beer and said in a booming voice, “A toast: to the death of God!”

“Ah!” they said in unison, though probably not one of them had ever read Nietzsche.

The conversation was about to turn to God, my favorite subject, when two other bums walked up to George the Highlander and said, “We’re ready. Everything’s set to go. We’re leaving tonight.”

George turned to me and said, “If you want to experience real freedom, come along with us. They’ve got a car, and we’re driving to Memphis, Tennessee, to raise some hell. You’ll find out about the death of God all right!”

Memphis seemed like a long way away, though it was only about a six-hour drive. I thought for a moment about the possibility of leaving everything behind and living a bum’s life. Why not? Aren’t cripples supposed to be at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder anyway? But then I thought about all the books I wouldn’t be able to write if I were living on the streets, because I wouldn’t be able to afford paper and pen. Even if I did manage to get ahold of paper and pen, how would I keep the paper dry in the elements? How would I keep all my papers straight if I was living on the streets? Besides, I don’t like to join groups, and these bums seemed to be part of some kind of brotherhood, which wouldn’t have suited my temperament at all.

I got up, still aching from the beating. George the Highlander could see I was uneasy at the thought of leaving everything behind. He shook my hand, thanked me for the beer, and said, “Sure you don’t want to come along?”

I told him I didn’t think I was up to it; that he was a braver man than I was, and all that freedom would have driven me mad. “Besides,” I said, “I have a hard-enough time being crippled. Being crippled and free might do me in.” George seemed slightly baffled by my words. I couldn’t decide whether what I’d said was intelligent or moronic.

I left the bums there, with their liquor and friendship, their wisdom and toxic odor, and I walked back to the world’s largest swimming pool, which Huey Long had built with misappropriated funds in the 1930s, much to everyone’s delight. I went back to retrieve my eyeglasses, my very expensive eyeglasses, but to my horror, they were gone. I’d tested fate, and fate had bitten me on the ass. There is no fate, of course. I had no one to blame but myself. How on earth was I going to read all those great books that were destroying my life? I walked back to my dorm, opened my notebook, and wrote:

I care so little what happens to me that I don’t even care enough to kill myself. Life is an annoying and sickly business, so ridiculous to be alive at all. I don’t blame those who want to blow up the world. They couldn’t blow the world up quick enough for me. I’m not bitter; I’m joyful. It is joy that keeps me alive. I am one of the most joyful people on the planet. When I die, it will be like nothing had happened at all. It will be wonderful to return to absolute nothingness again, from whence we came.

I fell asleep that night with the most amazing images in my mind: whole cities on fire, turtles being slaughtered on the shore of my childhood home, and the Immaculate Virgin stroking my cheek and whispering, Sleep well, Louis. It won’t be long now. It won’t be long at all before you are free.

There is no such thing as Christ, but the Virgin Mary is as real as flesh, as real as fire and stone.