Sarah slings a rifle across her shoulder and starts toward the glacier. She is one of our polar-bear guards. We follow her across the muddy ground churned through with gravel, flecked with cow tongues of snow. All around us snow is melting in fine-veined rivulets. The land tinkles, burbles, gurgles, squelches. The babble of spring.

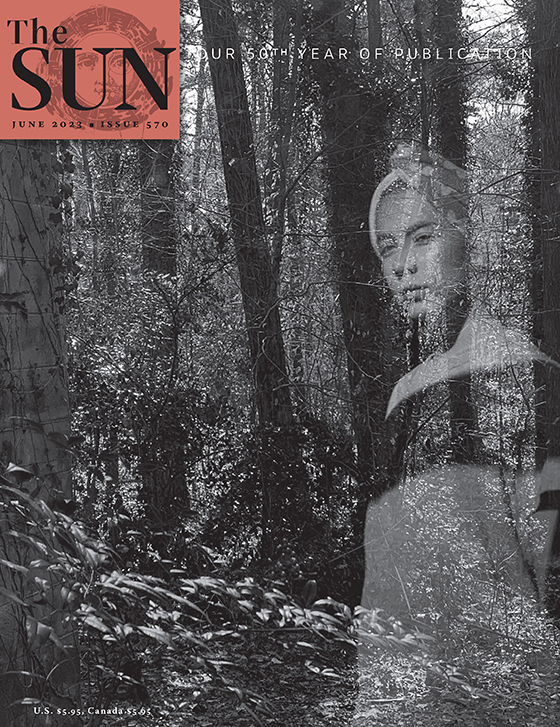

It feels like a warm April day from my childhood in southern Norway, but it is June, a week shy of the summer solstice, and I’m in the Svalbard archipelago, deep inside the Arctic Circle. We reach the edge of the glacier. It, too, feels familiar. I touch the edge of my impatience. The glacier’s underside has turned upward here, revealing a fine layer of silt: cinnamon on oatmeal. Or one of those tall roadside snowbanks blackened by soot, slowly melting in the sun. As if I were a child walking home from school, I feel an impulse to bend down and look for the first blooms of coltsfoot, their buttery shine. I remind myself that this dirty snowbank is part of a much greater body of ice stretching inland for miles and miles. In my mind I connect it to the Scandinavian ice sheet of ten thousand years ago, which ended in the place I used to call home, a gravel ridge built — only yesterday — by detritus from the retreating ice. Yet I cannot feel the glacier’s enormity as it wastes away in the sun. I try to photograph it, but all I capture, all I see, is grimy, dripping ice. Every photo obscures more than it reveals.