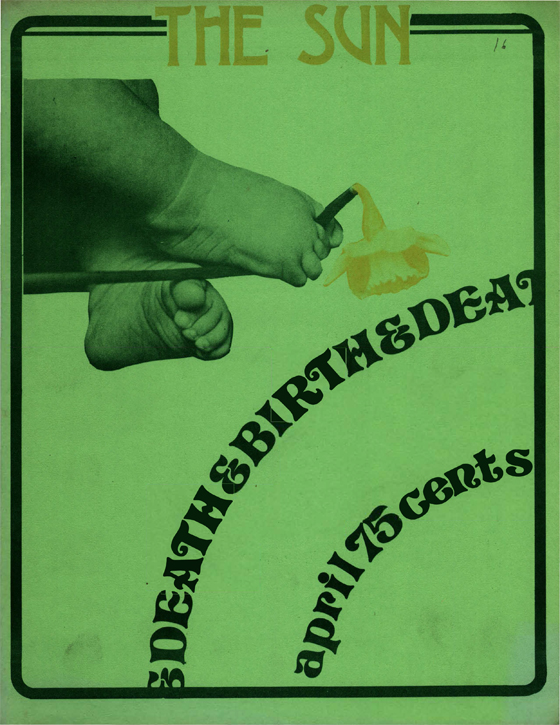

Death and birth is the theme of this issue. There are no more powerful, and less understood, words in the language. To demythologize one, we must demythologize the other. Yet our very vocabularies stand in the way.

From the cradle to the grave we are fed a steady diet of crap about our own mortality. The metaphor is not haphazard. “Man is the god who shits,” writes Ernest Becker. Our religions teach us we are immortal, created in God’s image; yet we are animals of the Earth, with its seasons of birth and decay. Death is all around us but as a culture we fear it, hiding the “shit” from view. The extremes to which we take this are the parameters of our social pathology, the American Way of Life. To avoid death, we drive ourselves to its brink. The cities we build, the cars we buy, the food we eat are a dead giveaway. We are stranded on the dry sands of our own biology, refusing to acknowledge the common source, the mystery, the sea before us. Even birth takes on the flavor of an illness rather than a miracle; now that the medical establishment has a near-monopoly on our Coming and Going, we are reduced to participants in this, too. If, in our national habits, we seem bent on collective suicide, perhaps that is our way of taking the matter into our own hands.

In any event, death will not be denied. If we try, we end up as “dead” as any corpse. There are as many different ways to understand this as there are religions, philosophers, artists and poets. Whether it’s couched in existential, spiritual or homespun metaphors, the idea is the same — to live in the moment, dead equally to false hope and hopelessness, in tune with the greater forces within and without us. This is explained eloquently by Jainindriya, in her article, “Transformative Experience,” and by Seth, whom we include again not out of cultish adoration but because of the singular clarity of his ideas. To some, his explanation of how “death” is no less a process of becoming than “life” will be old-hat; to others, desperate to pack in all of life’s experiences while there’s still a chance, it may suggest an alternative. The ultimate source for this information is, of course, ourselves. If, for the sake of profit, or purpose, or adventure, we forsake the seasons of our planet and our bodies for the deathless atmospheres of a corrupted ingenuity, if we move, not gracefully towards our center, but in some manic spiral away from balance and true self-poise, if we ignore the eternal validity of our being that endures the “little deaths” of life and the seemingly final death that awaits us all, we then deny not only death but life. Death, and birth, are, in some mysterious fashion, metaphors we have created for ourselves — not there, at the twisted edge, but at the silent center, where the terrors and confusions of human existence, all those challenges that seem to make no sense, are understood differently, accepted joyously, and gathered into the stuff of new worlds, and seasons yet undreamt.

THE SUN is a metaphor too, shaped as much by you, the reader, as the writers and artists who give it form. In that sense we are never “finished” with an issue, anymore than we can tell how, or where, one is born. There is less mystery about the nuts-and-bolts of its production, however; it is hard work, and it is costly. If you reflect that it costs us nearly $1 to print each copy (which sells for 75 cents) and that $1 happens, too, to be the editor’s hourly compensation, you appreciate the dilemma of $1 being, at the same time, too much and too little — a common enough impasse but one on which enterprises more worthy than this flounder. A cost accountant, looking over our books, might suggest an essay on the birth and death of a magazine. We have more faith. But that faith, in our ability to survive and prosper, rests on our ability to sell ourselves, which lands us squarely in other dilemmas: how to distribute more magazines, without sacrificing a low-key approach that honors your intelligence as well as our pocketbook; how to increase advertising by appealing to the enlightened self-interest of businessmen, rather than with inflated circulation claims; how to encourage those of you reading your friend’s copy of THE SUN to buy your own, since such sharing, which makes sense in theory, deprives us of badly-needed circulation revenue. There is no “answer” to any of this; we try different ideas as we evolve, and our slow but steady growth assures us we’re on the right path.

You can help. Introduce the magazine to new readers. Tell our advertisers you saw their ad in THE SUN. Subscribe, even if you’ve been buying the magazine regularly. Because of the percentage we pay our distributors, it means more to us to have your subscription; you save money, too. The introductory rate is still $7.00 for one year, a savings of $2.00 off the newsstand price.

For those who can afford to make a more generous commitment, we are offering three-year subscriptions for $25, six-year subscriptions for $50, and twelve-year subscriptions for $100. Since the price of THE SUN is likely to go up rather than down, taking advantage of one of these offers is economical. Finally, it tells us you’re there.

— Sy