It was hard taking my father to the public pool. It had wheelchair access, but he wasn’t in a wheelchair yet. Still, the ramp made it easier for him to shuffle up to the building and into the locker room, where he would sit and let me undress him.

Balboa pool was pretty quiet. On the way over, my father and I were quiet too. It was hard for him to talk, to form words and push them out. He wanted to conserve his strength for his swim, so his speech was slow, deliberate. As we drove up Stanyan Street, I listened closely to every word, to avoid asking him to repeat anything.

“Bee-you-tiful day.” He phonetically sounded it out so there was no mistaking the words. He smiled. He liked going to the pool, and he especially liked going anywhere with me.

I parked the van and helped him out of the passenger seat and onto the sidewalk. I closed the door behind him and, with my arm around his waist, we slowly worked our way up the ramp to the building. At the double glass doors, we had a little trick where he would lean against one door as I pushed and held open the other door with a foot. In the lobby, we repeated the routine. Sometimes people helped. Sometimes they stared.

In the locker room, I sat him on a skinny bench. I kept up a comic banter as I undressed him, sniffing his socks and saying, “My, these are ripe.” I was trying to keep a smile on his face, and on mine. Finally, I had his clothes off and a swimsuit on. I quickly put on my own suit. “OK campers, everybody into the pool,” I said, and we slowly marched out of the locker room.

Some of the faces in the pool looked up. It must have been hard for them not to stare. My father weighed just over a hundred pounds, arms loosely dangling like limp rubber bands as he walked. His head rested chin to chest, giving the neck a strong curve. To navigate, he lifted his head periodically as he walked, turning it from side to side like a turtle, complete with exaggerated blinks as he surveyed the surroundings.

I thought about how people stared. Here was my father, who spent his whole life being different. His family called him the black sheep. Because of his radical left-wing politics, he was like a foreigner in all the conservative little communities we lived in during the fifties and sixties. It wasn’t until we came to California that he finally fit in somewhere.

My mother warned me not to talk about some things with him, like his short, unpleasant experience in the Communist Party, or why he didn’t pursue a career more in keeping with a political-science degree from Yale.

He had numerous menial jobs after Yale, including organizing factory workers in small, dirty workplaces. After I was born we moved to the suburbs. He became a small-time truck driver and then started his own moving business, which my mom helped him run. I remember playing in the moving vans and the barrels they packed stuff into in those days. You’d get inside the barrel and another kid would roll you around in the street till you were sick or had crushed your fingers gripping the rim.

He went back to school and got another degree, in library science. He became a librarian, working in the public libraries. He had a brief stint as a university librarian. Always restless, always unhappy.

We moved to a huge Victorian house with a big chunk of property that contained a homemade in-ground pool with a leaky liner. An acre of true woods stood in back, big maples, locusts, and spruce. There was a big barn-garage with a hayloft above it, where I slept out with friends, snuck my first drinks, and kissed my first girlfriends. My parents instilled good socialist work ethics in me, as I tended the rough and scraggly property with patchy lawns. I would mow, rake leaves, clean pool filters, drain hoses, dig fence posts, paint everything wooden that didn’t move, and collect a pittance of a buck and a quarter a week — although I often successfully negotiated for more.

I hated organized sports and liked being left alone. I was a bookworm, imitating my old man by reading almost everything I saw. I swam in the summers and into the fall, begging off the annual draining of the pool until the leaves began to cover it and clog the filters. In winter, I’d go skiing with the richer kids. I told them we should stay out of Vietnam, and they looked at my shaggy hair, then turned around in the bus seats in silence.

My father picked us up and moved us to California in the seventies. After a couple of years in Mendocino, he left us all — joined a commune and built himself a little trailer home that was tacky even by the commune’s standards. He sat in there re-reading his Marx and Engels, cocooned in a shell, seemingly at peace. Then came the symptoms: a problem holding his knife and fork; a slight slur of speech. The diagnosis was Lou Gehrig’s disease. His life was ending soon.

I helped him lower himself on the aluminum ladder into the pool. He made the final jump, planting himself squarely on the pool bottom. His legs were still fairly strong, as the disease ravaged his upper-body muscles first. He walked away from the ladder, happy in the warm water. As the water rose over his waist, he lifted his head and made a funny it’s-cold-when-it-hits-your-balls face. I laughed; he could still make me laugh.

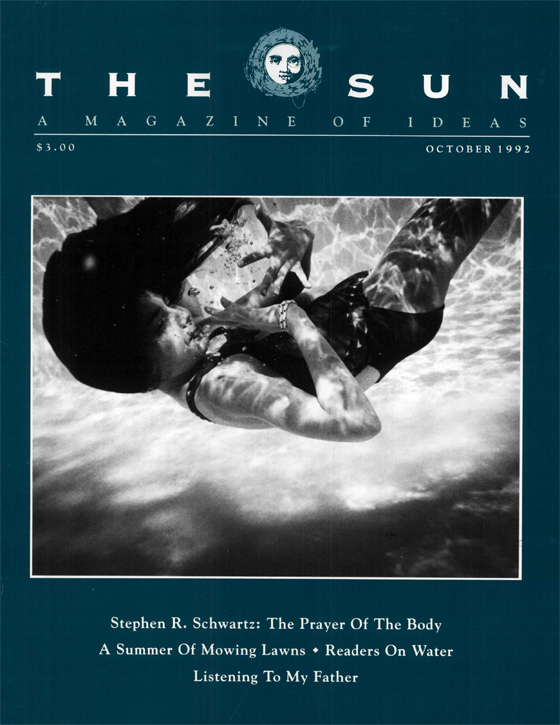

I jumped in after him, ducked my head under, the chlorine stinging my eyes. We walked to where the water covered our chests and helped carry our weight. Now he was free. Almost magically he could raise his arms. He flung them up with an effort to grip the side of the pool, and let his legs drift up so that he was prone. He started kicking the way kids do when they first learn how to swim.

I looked around and saw a group of kids frolicking in the shallow end. They were a cosmopolitan San Francisco bunch — black, Oriental, Mexican. On second glance I realized they were some sort of special group, old and young kids with mildly distorted faces. A couple of them stared in our direction, at the man who also looked different and used the public pool.

The public pool: my father was adamant about going there, not to some private gym or club. He felt strongly about public services: public pools, public transportation, public libraries, public television. Even now, with the gross inconvenience and spectacle of his infirmity, he put his money where his mouth was. “Balbo-a is — fine,” he had said.

He let go of the side of the pool, gracefully drifted back to a standing position, and smiled at the children. They continued splashing and playing.

After I worked his arms and legs a little, dislodging some of the tension, exercising and stretching the muscles that he couldn’t use himself, I asked him if it was all right to swim a few laps on my own. He nodded. “Thanks,” I said. “Just a few. Don’t drown — I’ll get yelled at.” He grinned.

I swam furiously, passing his familiar shorts and legs the first lap, alternately swimming under water and above. After racing by on my third lap, I began a succession of somersaults: three, four, five, all in one breath, until the water ran up my nose just like it did when I was a kid. I stood up and took my bearings, slightly dizzy. I was a little past where he was standing, swishing his arms to and fro. Suddenly I wondered what I would do with my freedom when he died. Looking down at the water’s rippled surface, I saw the reflection of his face, and in it I saw his own human suspension in time, and his final trust in the natural order of things.