Going home, as if home were still a possibility, or, like those other shadowy and relative values of our age — love, honesty, rationality — nothing more than a momentary echo of something past, and nearly forgotten, a smudge on the map, a torn page from the history book, when families stayed put, when the heart was forever, when politicians were statesmen, when faith was an arbiter at the edge of learning rather than a substitute for reason.

Or is that America as much a fiction as the tales told, by our teachers and Presidents, about this America? Has home ever been a possibility in a nation so dedicated to change and the dizziness of movement, a nation half-drunk on the notion that if you’re not happy where you are, you’re probably just in the wrong place — a belief as fiercely owned by twentieth century suburbanites-on-the-move as nineteenth century frontiersmen.

On the move, on the make, we are a people still too naive, too afraid, and perhaps (and this, only future historians can judge) too wise to settle down, for our journey is as much within as without; the frontiers of consciousness engage the best of today’s minds just as the mountains and deserts tested an earlier generation. And here, too, there is no going home again; for the spiritual journeyer, there is no trusty map, and the most dedicated become the most lost before the journey ends.

And the looking for home continues. In the cities and the suburbs we are a rootless citizenry, and if, in the countryside, the farmer is somehow more at peace, it is a state unlikely to endure the cruel harvest of the 6 o’clock news and the strangeness of a homeland it will take more than hard work to fix. The fact of feeling rooted, at one, settled yet somehow free — call it home, or security, or peace of mind — becomes more and more our goal, less and less our condition. And the more it seems to recede, as fact, the more does its possibility seem to beckon us onward — along the Interstate, our belongings in backpacks or filling huge trailers; in the great cities, where we call ourselves neighborhoods and universities and seem always to be striving for an identity never realized; and on the more private highways of the mind.

The distance closes: three thousand miles, measured in the cruel, monotonous rhythms of cafes, gas stations and car lots, the majesty and tyranny of desert and mountain, or measured in hours (but endured, as the Buddhists endure torture, moment by moment, for the full measure of such a journey is too vast to comprehend). America becomes real for me again and incomprehensibly gigantic, a mother fully the equal of the dreams moving towards birth within her — as the three of us move, in the cramped and strangely transfiguring fashion of coast-to-coast travel, towards our separate deliverances, if only from the growing numbness of driving, and towards a clean bed, and the other simple pleasures of home.

Home, yes, for this is nothing more than a letter home, three weeks gone, and feeling the need to be careful of what I say, for these weeks have been soured by carelessness in word and gesture, as I returned to the old and familiar with a friend who had changed too much (or perhaps not changed at all; understanding love affairs, like understanding America, is an effort seldom successful, always costly) and wanting now to begin more deliberately, lovingly, honestly — as a gesture of the truest independence to which she encourages me and to which, like some new America, reluctantly but necessarily leaving Europe behind, I now turn, leaving these sorrows to rediscover my home, and the friends that make it home, and to learn, as America learns, what independence truly means.

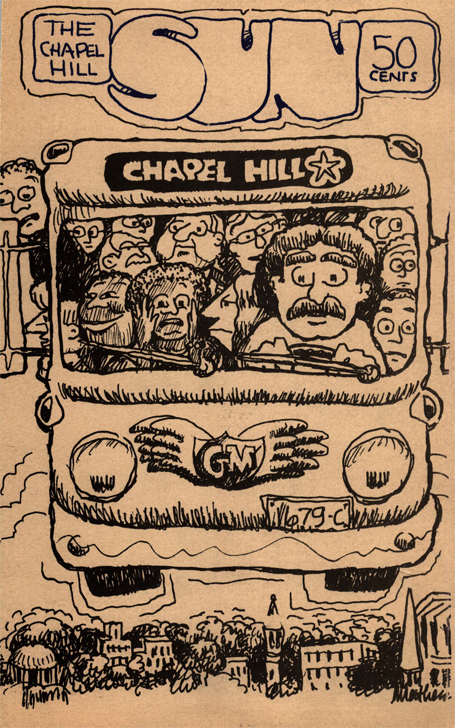

To my friends, then, greetings, from this tired American heart, moving swiftly towards you, back to all the public and private places we call home: the kitchens and the bookstores and the backyards of Chapel Hill; and the country houses, part of a new American architecture of funk and imagination and plain common sense; and anywhere on Franklin Street, that living museum (vandalized to the extreme but surviving, somehow, with dignity) of a piece of America past and nearly forgotten; and the rest of that psychic geography: the broad psychedelic boulevards; the avenues of love and discovery; the path with the heart we travel together, American journeyers all: the gentle philosopher, who dances, with holes in his pocket, from one crazy job to the next; the young woman, who bears her magic like a child and her child like the trust of nations and if not American by birth has become so by her faith in innocence and the open future; the artist whose stroke is so fine and generous and who seems, sometimes, the barely plausible creation of his own zaniest imaginings; the pilgrim, earnest and foolish and wise beyond his own understanding, who carries our search for love to all the likeliest and unlikeliest places — and all the others: my family: healers and madmen and journalists of their own finest journeys; the ones who live simply, or stylishly; the ones I love, and attend to, or love, and fear — walking arm in arm now, as the only possibility, towards whatever future America provides for its children. Wait for me. I’m almost home.

California-Arizona-

New Mexico-Texas

Oklahoma-Arkansas

August 5-6-7