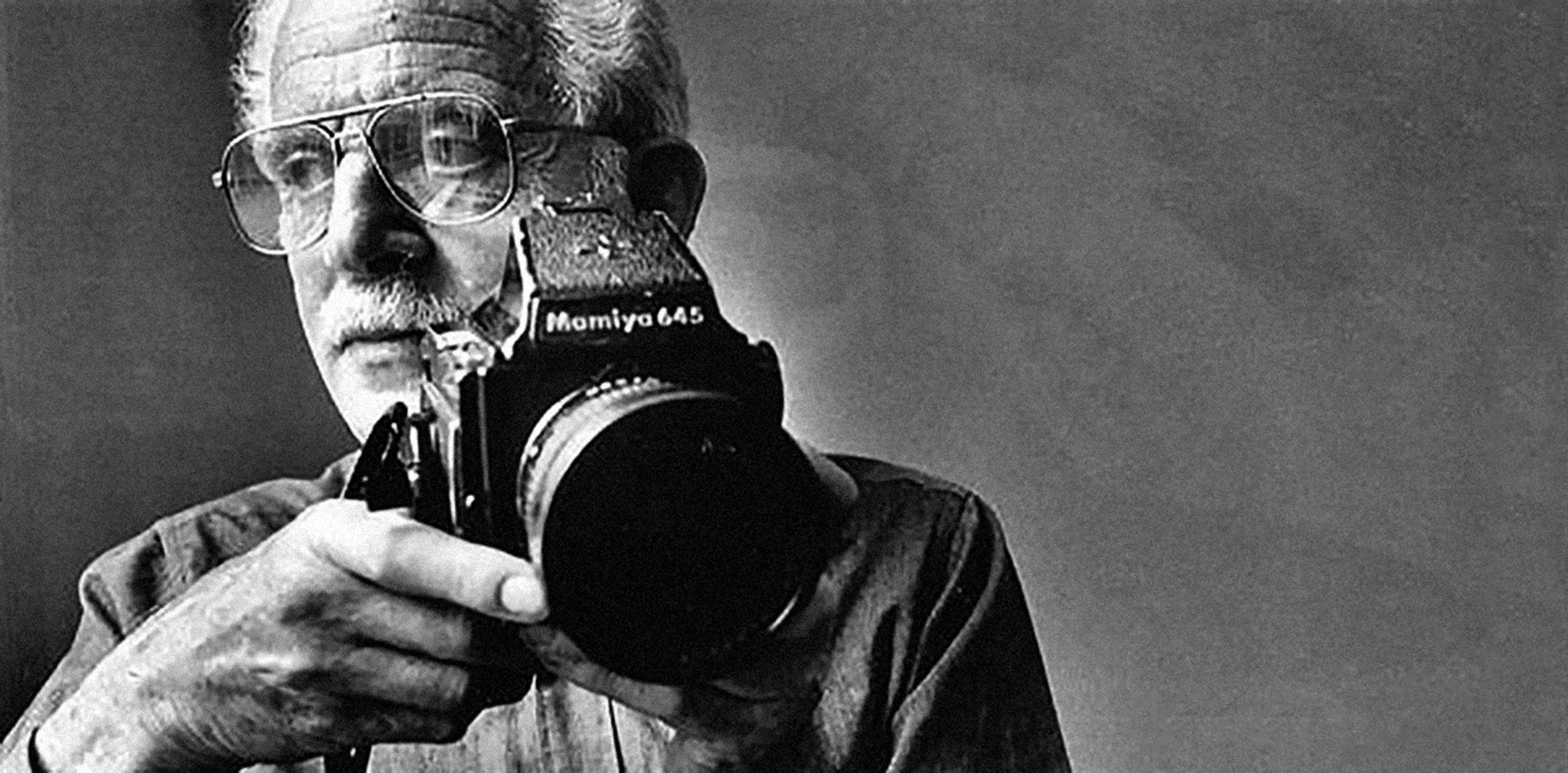

Photographer and longtime Sun contributor Clemens Kalischer died this past June at his home in Lenox, Massachusetts. He was ninety-seven.

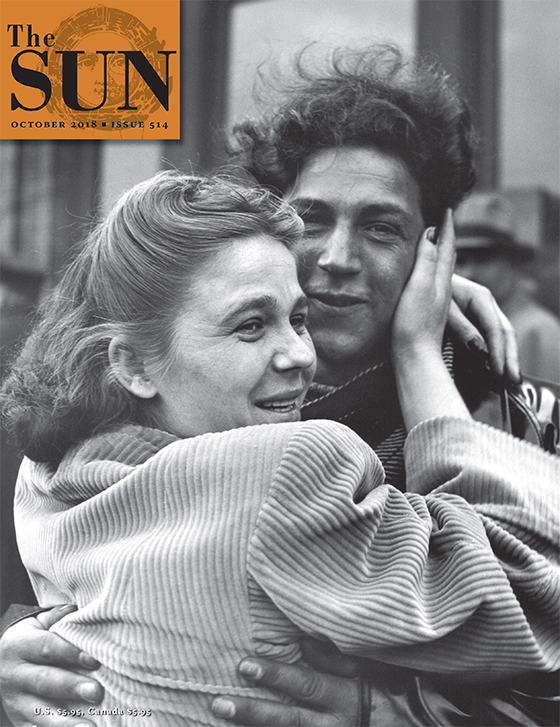

As we were deciding how best to honor him, the news was filled with stories of immigrant children being separated from their parents at the southern border of the United States. Many of these families had come to the U.S. seeking asylum due to the violence in their home countries, and their plight reminded us of a series of photographs that Kalischer had taken as he was getting his start in photography.

After World War II Congress voted to allow thousands of European war refugees into the U.S. Whenever a ship carrying these “displaced persons,” as they were called, came into New York City, Kalischer would go to the harbor to take pictures of the new arrivals. He had come here as a refugee himself not long before, at the age of twenty-one, and he recognized the fear and expectation in the faces of the men, women, and children. Because he’d had the same experience, he said, he was able to move among the refugees and photograph them without troubling them. “He had this immense connection to these people,” his daughter Tanya says. “When he took those photographs, it came from a place of empathy.”

The photos on these pages were all taken in 1947 and 1948.

Born to Jewish parents in 1921, Kalischer grew up in Nordhausen and Berlin, Germany. His mother was a physiotherapist, and his father was a psychoanalyst. As the Nazis came to power in 1933, his parents fled the country, taking Clemens and his sister with them to France.

After the outbreak of World War II, Kalischer was arrested by the French government as an “enemy alien” and forced to work in eight labor camps over three years. His parents didn’t know his whereabouts until by chance Clemens was reunited with his father at one of the camps. Clemens’s mother and sister were being held at a farm nearby, and with the help of the Emergency Relief Agency as well as several well-connected friends — including Sigmund Freud’s daughter — the Kalischers got out of France and narrowly escaped being sent to the concentration camps.

When he arrived in New York City in 1942, Kalischer weighed just eighty-eight pounds and spoke no English. He found work as a copy boy with a French news agency, and one day, when the regular photographer was unavailable, he was assigned to take pictures of a French luxury liner that was scheduled to be scrapped. Already a lover of photography, Kalischer impressed the editor with his work, and the accidental assignment became the start of a lifelong career.

He carried his camera around the city, practicing being “as invisible as possible,” as he put it, so he could capture images of people going about their daily lives. His work was included in exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art and appeared in the book The Family of Man, put together by photographer Edward Steichen. He had photos published in The New York Times, Life, Time, and Newsweek.

Kalischer settled in the Berkshire Mountains of Massachusetts and married fellow Holocaust survivor Angela Wottitz. They had two daughters, Cornelia and Tanya. In 1965 he opened the Image Gallery in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and over the years he exhibited the work of up-and-coming artists and continued his career as a freelance photographer. In his later years he joined the organization One by One, which aims to promote healing by bringing Holocaust survivors and their families together with former Nazis and their descendants (one-by-one.org).

Visiting new places was one of Kalischer’s great pleasures in life, and he often traveled the back roads of the country, taking pictures of whatever interested him.

One day in 1999 he stopped by The Sun’s office, parking his VW camper in back. He was in town to document the magazine’s twenty-fifth-anniversary celebration and to photograph our staff at work. Not surprisingly, he told us to pretend he wasn’t there. His goal, as it had been throughout his career, was to capture the unguarded pose, the natural expression, the human moment.

— Ed.