My insomnia began just when my baby girl started sleeping through the night. Anytime my head hit the pillow, my heart pounded like a million galloping horses, and I would tremble and sweat and eventually get up and stand on our back porch to beg the gods for peace until I heard the birds chirping, inaugurating a new day, which I would spend dragging around my girl without even a modicum of rest. None of the herbs, medications, or mindfulness techniques I tried were able to move the needle. The worst of the experts I saw was a perky-breasted young woman, who’d certainly never had a child rip through her vagina, who said, “When I’m having trouble sleeping, I just think of a beach!” I wanted to throttle her. I was beyond beaches, and yet, after our overpriced consultation, I did begin picturing myself sitting in the sand on the Florida beach of my childhood, my parents drinking beers in lawn chairs, not long before my mother walked out.

By the time my daughter turned one, my husband was so desperate to solve my problem that he recommended I consult my father, the experimental scientist, even though we had made a pact that I would avoid my father’s magic once our daughter was born. “At this point you should turn over every last stone,” my beloved mumbled as I gave up on my visions of Florida and drove in the middle of the night to my father’s apartment across town. I found him smoking on the balcony, conferring with his own demons, his cigarette glowing like a solitary candle in a dark and endless forest.

“It has been a year of hell, Papa. I do not see the end of it,” I said.

“Oh, everyone sees the end eventually,” he replied, unimpressed by my struggle.

“If I don’t get some sleep, I’m going to jump off a building.”

He tilted his head, peered at me, and saw that I was serious. “I will do what I can,” he told me as he lifted a finger and descended to his laboratory in the basement of the building. He returned with a sailboat-shaped carafe he and my mother would drink from before she abandoned our family. He stroked it gently as he gave me my instructions: I had to catch a single tear of my daughter’s in the carafe, swirl it around, then think of a relaxing place before I sucked it down. This was eminently doable. I thanked my father and told him to get some rest.

“Rest is for simpletons,” he said. “I would rather converse with the stars.”

I left him to his pointless dialogue, finding no romance in his pain. I drove the carafe home, past all of the houses with their lights off, where every soul on earth except me and my father rested soundly. I parked in the driveway and managed to doze in the car, hugging the carafe, until I heard the morning birds. This was already a promising development.

I found my husband and daughter playing in the living room. My girl was a goddamn angel, and my husband was grumpy but good-hearted. I watched my two favorite people, whose minds were not diseased and who were able to drift off the second their heads hit the pillow, and I thought I would give up ten years of my life to remaster this skill.

“Bad night?” said my husband, looking me over.

“Bad year,” I said.

Shortly after that, he left for his last day of classes for the semester, and once again I was alone with my daughter and trying not to off myself before evening.

I lugged around my sweet girl and my broken mind and body until my husband returned and it was time to put her down for the evening. I carried her upstairs and followed Papa’s instructions — or I tried to, at least. My girl always cried before bedtime, so it was easy to catch a tear in the carafe, but I did not stop there. I caught a handful of tears, just to be safe. I was certain I needed more than the instructed dose.

I swirled my daughter’s tears, which mingled with the decades-old tannins of my parents’ long-obliterated love. Then I thought of Florida and sucked the elixir down, kissed my girl’s forehead, and lowered her into her crib. I watched my angel child, marveling at how she did it, moving from wakefulness to sleep without thinking twice.

That night, while my husband graded exams downstairs, I climbed into bed feeling like I was in full armor, for once unafraid of entering my battleground alone. I was sleepy and relaxed and walking on the beach in Florida, hearing the sweet crashing of the foamy waves. Soon, I knew, I would be carried away. I was not worried about having drunk the extra tears, because I needed more help than Papa realized. I was certain I had done the right thing as I fell asleep effortlessly.

I opened my eyes to the inquisitive faces of my daughter and husband, who informed me that three full days had gone by.

That first morning my husband was not alarmed. He just thought I needed to catch up on rest after months of wakefulness.

I climbed out of bed refreshed, eager, excited, overjoyed. I’d spent a short vacation in Florida! I was cured! I could love life again! I took my daughter out for a walk and oh my God I loved her so fucking much! She was a cherub, my husband was perfect, the world was a welcoming and benevolent place. Even my derelict students were not so bad. How had I not seen it this whole year? I pushed her stroller to the coffee shop, and she was babbling and smiling, and I wanted to squeeze her to oblivion, but instead I scared the barista by giving her a hug. Then I came home, put my daughter down, and made passionate love to my husband. My body and soul were working again.

“It’s about time,” he said.

“Indeed,” I said, closing my eyes, still naked. “I’m back, baby,” I added, before drifting off.

I woke up a day later.

Only then was my husband distressed. He stood over me, my beautiful baby girl in his arms.

“I might have overdone it,” I admitted as a big, powerful, soul-affirming yawn escaped my lips. “But I still feel so very relaxed.”

Things fell into a new routine after that. I would be awake for one glorious hour each day. This was untenable, of course. Classes had just let out for the summer, but soon I would have to teach at the university. Papa helped with our daughter when he could, but he and my husband could not split all the caretaking. Reluctantly I went to visit Papa one evening and explained what I had done. He was mortally disappointed.

“You never listen,” he said, shaking his head as he told me there was no reversing it.

“I won’t miss being awake for a while,” I said.

My father was once again standing on the balcony conversing with the stars, having no apparent desire to treat his own sleeplessness. As I was leaving, he inquired about the carafe: “If you don’t mind, I would like it back, please.”

I considered asking why he wanted the damn thing if he was never going to do anything with it, but I did not see the point. If he wanted to be eternally reminded of Mama, who was I to stop him? I just nodded, feeling a yawn coming on.

My summer of relaxation proved very stressful for my family. I tried to stay awake for longer than an hour, but nothing worked. I drank a liter of coffee. I locked myself out of the bedroom. I stood on the woods-facing back porch that I associated with terrified wakefulness, but it failed to have its intended effect. I saw another sleep specialist, who was flummoxed by my predicament even as he charged me the equivalent of a month’s rent. I even blasted death metal at top volume, but nothing would keep me up past my one allotted hour.

Before his classes started in the fall, my husband hired a full-time babysitter, a dour-looking redhead who was only a few years younger than I was and who judged me for my sleepiness. Once, I heard her cursing me as I nodded off.

“Torpid tramp,” the woman muttered outside my room, before I was greeted by sweet oblivion.

My daughter, who began talking and taking her first steps while I slept, did not begrudge me, at least.

“Sleepy Mama, sleepy Mama,” she would chant when I attempted to read her a story in the last minutes I was awake, my eyes growing heavier until my husband came in to replace me.

“There she goes again,” he would say to no one, not without bitterness, and I would slip into the abyss once more.

I must admit, the situation did not trouble me as much as one might expect. It was true that I missed my daughter and husband, but I was relieved to have to stop teaching, thus avoiding the dull, hateful gazes of my composition students. And visits with my father became more pleasant because there was no time for conflict or philosophical ruminations. “You are at peace,” he would say, sweeping a hand over my head, disappointed for some reason.

My husband and I would still make love and share half a glass of wine, when I could stay up for it, our relationship distilled into one perfect hour each day instead of an endless slog in which it felt impossible to find even a minute of love. And, best of all, I no longer feared my bed. It was a warm, comforting nest I would climb into, already hearing the waves crashing and feeling the sand between my toes and knowing relief was on its way.

My daughter’s hair reached her shoulders, and she got big enough to go to school, though the pesky babysitter still watched her afterward. I tried to give my darling the most of my daily hour, feeding her blueberries or reading her educational books or telling her about the preciousness of life, and I believe she still loved me. In spite of my limitations I managed to conceive a son and give birth to him, after sleeping through most of my pregnancy — the envy of every childbearing woman. My son was a sweet boy who as a toddler sang, “Rock-a-bye, Mama,” and stroked my hair as I prepared to sleep.

Not long after that, I lost Papa.

I found him on his balcony with a note. I am dying — likely dead by the time you find me. Take good care of my things and yourself, he wrote. I planned a little funeral for him, threw out everything in his apartment, and packed up his precious basement laboratory, including the sailboat carafe, which I placed on my nightstand. It took me more than a month to complete the task, one hour at a time. It was strange, mourning while feeling so relaxed. I’d hoped wild, dark grief might keep me up, but nothing could stop me from hitting the Florida shore.

The years went on. My daughter had a gorgeous wedding, or so I am told, and not long after that, my son graduated from high school. The babysitter no longer needed to watch over my children, but she had continued taking care of my husband, it turned out. When my son was college-bound, my husband declared that he and the sitter were getting hitched.

“A few sleepless nights, and I lost you completely,” he said. “It could have been different. I would rather have continued our life together.”

“You can still be with me.”

“An hour a day isn’t enough.”

“Many relationships are founded on less,” I said, hurt that he had given me the news at the beginning of my hour, so I could not immediately drift off to end the pain. It made sense that I should be the one to leave, so I went upstairs to begin packing. The first thing I landed on was the carafe. I clutched it as the sitter-mistress made her way into the room, looking triumphant, followed by my husband.

“Lethargic floozy,” she said, and my husband turned to face the wall, his shoulders sagging.

I considered insulting her back, but instead I took my carafe to the back porch. Ages ago I had stood on that same porch in my pajamas, begging those woods to help me fall asleep. Anything, I had told the heavens, I will do anything at all for peace. Was I better off now, never having to worry about rest while being utterly alone? Yes, I decided, I would rather be relaxed and alone than surrounded by friends and family and filled with terror, craving the abyss. Yet as I looked up to where my husband’s and the sitter’s silhouettes were passionately intertwined, I was filled with rage. Why couldn’t I have had the love and the relaxation? I chucked the carafe against a tree, shattering it into pieces.

I thought of my parents sharing a drink from the carafe, my young father and my gorgeous mother, whom I no longer blamed for leaving when things became untenable. I saw her beautiful, tragic face before me, and I loved her still. And then Papa appeared, as I’d known he would.

“You can do what you like to yourself, but why did you have to obliterate my special carafe?” Papa said. “You will suffer the consequences.” He was trying to sound angry, but I could tell he was happy to see me.

“What consequences?”

“You will find out soon enough,” he answered, before disappearing into the ether.

Papa’s warning did not scare me. In fact, seeing him was kind of nice, and for a minute I felt slightly less alone. I admired the sun’s reflection on the shards of the carafe until my heart and eyes grew heavy.

Years went by, enough time for my children to have children and for my husband to fall out of love with the sitter-mistress, though they remained married. My body was ready for release. I left my bed at home for my deathbed in a hospice, and I must say it did not make much of a difference. I was not scared. I knew dying would be just like succumbing to the sweet release of sleep, but forever.

My family visited me on my last day alive, when I was beyond making conversation.

“I only spent a few thousand hours with her, but she seemed nice,” said my daughter.

“She was always yawning,” said my son. Then he grew despondent and sang, “Rock-a-bye, Mama,” one last time, and my husband and daughter even reluctantly joined in for the final verse.

“She had a nice face. Troubled but full of character,” said my husband, and I could feel his wife bristle at his side. She was the last to leave the hospice room.

“Rest in peace, you soporific slut,” she muttered, before walking away.

I heard her vibrant, unsleepy footsteps clacking down the hall, and then I went to Florida for good.

I don’t know how long it’s been since then. Some days I think it’s only been a few years, but other days I wonder if a century has whirled by. There’s no night in Florida. Sleep doesn’t come when I close my eyes, only an endless bout of wakeful peace. Soon enough, though, as Papa had warned, the situation became unbearable, and I cannot be blamed for trying to end it. This is my punishment, I suppose, for breaking that damn carafe.

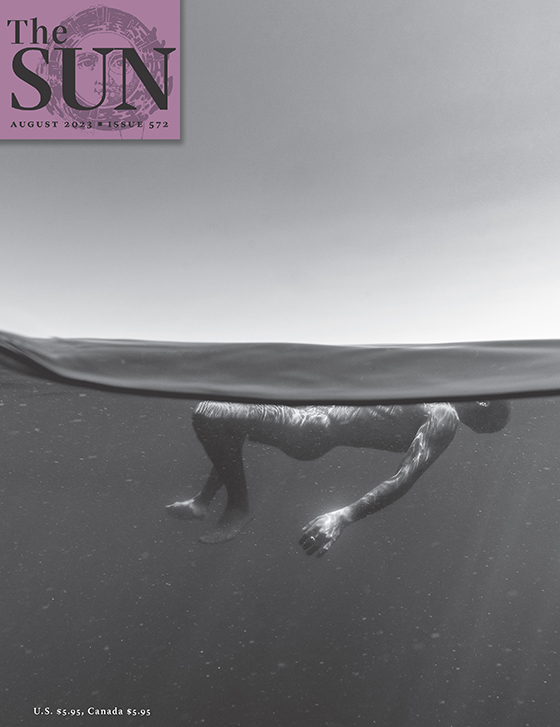

The first time, I tried to drown. The second, I choked on sand. The third, I slit my wrists with a seashell, rivers of red befouling the pristine sand. But each time, the ocean just spit me back up, healthy and naked, like the sweet girl who had come into the world and begun my unspeakable troubles.

After the seashell incident I gave up. This was my lot in death: permanent relaxation. I tried to make the most of it. I swam and thought of my children, and I waved madly at the birds who flew overhead, my only companions. One day, as I watched them, it occurred to me that I could try to leave the beach. I had assumed it was endless, but I had never explored very far. I tried going inland, but I couldn’t push through the thorny wilderness. So I just walked and walked along the sand, dreaming of my daughter, and before long I was right back where I started. It turned out I had been on an island the whole time.