It’s Ladies’ Night at the Shriveled Gun, but none of the women who used to come around here do anymore. Lauren and I are the only ones sitting at the bar. We are freelance theater critics who spend most weeknights in cramped, black-box performance spaces where the walls sweat. Once a week we have a girls’ night out, take a break from watching actors play other people and instead watch real people play themselves. This Manhattan bar, which used to be trendy with its bad lighting and punk-rock vibe, is the perfect place for it.

“There,” I say, when the right target finally walks in. “Look at that guy. That guy is a living punch line.”

The man in question appears to be around my age—early thirties—and is wearing a day-glo-orange knit hat and a messenger bag slung across his chest. He is handsome in an artist-in-the-attic sort of way, with sinewy arms and a slim build, but he is trying too hard to pull off the look. He approaches the bar, orders a Scotch, pulls out a book, and begins to read.

“That guy is asking to get punched,” Lauren says.

I’m eager for other people to notice Book Guy, but only I do. My stares seem to disrupt the concentration holding him to the page, and he looks up. He has seen me.

“Hello,” he yells over the din.

Up close, Book Guy has light freckles and a sliver of space between his front teeth. He shows us what he is reading: poetry by Rumi—an edition published by Random House in the eighties, he says, and he traces the lettering on the cover with his thumb. It’s intimate, the way he does it, like he’s touching the gilded edge of a Bible or the skin of my back.

“Are you readers?” he asks. His mouth twitches when he smiles. It’s almost vulgar and makes me want to pull back and lean closer to him at the same time.

“Sure,” I say.

“What do you read?”

“Faces.”

Without skipping a beat, he swivels my barstool toward him and brings his face so close to mine that all I can see are the dark circles of his irises. “Have a look,” he says. And though I still feel the impulse to mock him, at the end of the night I let him enter his number into my phone. He saves the contact as “Matt.” No last name, just Matt—as if already that sure he’s the only Matt who will matter.

On our first date, at a Mexican restaurant just off the West Side Highway, Matt declares that the two of us are meant to be.

“It was electric when we met,” he says. “Magnetic. I just knew.”

“Really.”

“Really! You wouldn’t believe it. I was reading these lines—” Here, he closes his eyes and recites:

Close the language-door and open the love-window. The moon won’t use the door, only the window.

“And then I looked up, and there you were.”

I am not sure how to respond, although laughter is probably not the best choice. Sangria shoots up my nose, and my laugh turns into a cough. “That’s me,” I say finally, “your moon.”

I think he might be offended, and maybe it’s better if he is. Already I feel as if I have misled him. He works days as a freelance software engineer and DJs at night. He writes letters home to Michigan. Every other Sunday he volunteers at a crisis hotline for troubled teens. I thought he was a poseur, said yes to this date just for the sex. But as I sit back and stare at him, it occurs to me that this man is genuine. He’s too good for me, and it’s best to let him know that now.

I tell him he doesn’t want to date me. First of all, I don’t date seriously, and second of all, I don’t date men like him. My day job is at a bank, and the men I date are meaty and calm, with nerves sanded down by years of recreational athletics. They rise from office chairs with the loose, side-to-side gait of having just finished a game. They don’t read Rumi poems. For them the moon is just a moon, and that makes their feelings for me safe and uncomplicated. It puts me in control.

Matt doesn’t seem convinced, so I tell him another story: When I was in college, I studied abroad. While staying in a hostel on the outskirts of Rome, I saw a mouse get killed by one of those old-school mousetraps with a wire snapper and everything. The whole contraption jumped about a foot in the air, and the half-dead mouse landed close to my feet, still in the trap. As I watched it spasm and die a gruesome death, I couldn’t help feeling both tenderness and disgust. “When I leave a man,” I say, “it’s kind of like that.”

I’m trying to see if he scares easily. I’m betting he’ll get up and leave. Or maybe he’ll finish his drink and we’ll go back to his apartment and he’ll fuck me once for the hell of it then never call. Instead he gives me a smile that’s halfway between a grin and a sneer, revealing the slit between his front teeth, and he says, “So, what, you have commitment phobia?”

We are living in a world where there is a name for every problem. “Sure,” I say. “Commitment phobia.”

He lets out a little sigh and leans back in his seat. “You never really liked those other men. Those men let you push them around.”

The fairy lights strung along the walls reflect off his glasses. There is a kind of certainty in his posture that I haven’t felt myself in years. He doesn’t fear me. I think I like that.

On our fifth date I take Matt to a new off-Broadway theater on the West Side. The play is King Lear set in the modern day, and the interpretation is uninspired—an old man divvies up his estate among his daughters while he plans to commit suicide—but it has been cast superbly. Cordelia is stately, her performance tender and controlled. Lear exhibits range in his portrayal of the self-absorbed, regretful old man. Somewhere in the middle of the second act Matt lifts his hand from mine, and I glance over at him. I have never seen him so still. Afterward, as the two of us walk silently out the back door of the theater, I’m feeling a little queasy, a little loose—good theater is not unlike having too much to drink. I begin to say this when I see that he is crying.

In the alleyway behind the theater, he steadies himself against a wall.

“That was a lot,” he says. “How do you watch stuff like that every night?”

“You get used to it,” I say.

The truth is that it’s been years since I felt the way Matt feels now. Whatever it is that makes him read Rumi poems in public is the same thing that allows him to be wrecked by theater the way I wish I could be. There is something hard in me, a seedlike malignancy. I can’t say how it got there or when, but I can’t remember the last time I felt pure love or sadness or joy. It’s always a mix of things, some confused and muted in-between.

“Why do you like theater so much?” he wants to know.

I stall. “Why do you like music?”

“I asked you first.” But he thinks about it and responds anyway. “Because it takes me other places.”

“Me, too,” I say. “Theater takes me places, too.”

“That was my reason. You have to come up with something different.” He wants me to give him a little part of me that I’ve never given anyone else.

“I like how everything in a play is packed with meaning. I like how the characters take chances because they only have about two and a half hours to live through. It’s inspiring.”

“Hmm,” Matt says. “I hadn’t thought of it that way.” Looking at him in profile, lit by the bulbs strung above the back alley, I see that his lashes are lighter at the tips. “Have you really never been in love before?”

“I’m in love with theater.”

He nods like he understands, but I wonder if our definitions of love are the same. To me love is more than just passion. Love is an animal inside you that must constantly be fed, that grows and takes up more space until there’s no room left for anything else. It strikes me as strange that people want to fall in love. It’s something that should be restricted to the realm of plays, TV, movies; something experienced by fabulous people with huge production budgets behind them. Looking at Matt, I think: You’re one of those people, aren’t you? A leading man. As confident as you are unreal.

“Do you want to write theater reviews full-time?” he asks. “Is that what you want?”

Things seem so easy when you put them like that: What do you want? Like choosing from a menu.

“No,” I say. “I like my job at the bank.” Being a teller isn’t glamorous, but I have come to enjoy the smell of money, the counting and recounting and knowing that all is where it should be. I like having the ability to zone out, forget that I’m me, and that I could be someone else. I suppose this is what I love about theater, too: that when the lights dim, my consciousness detaches itself from my body.

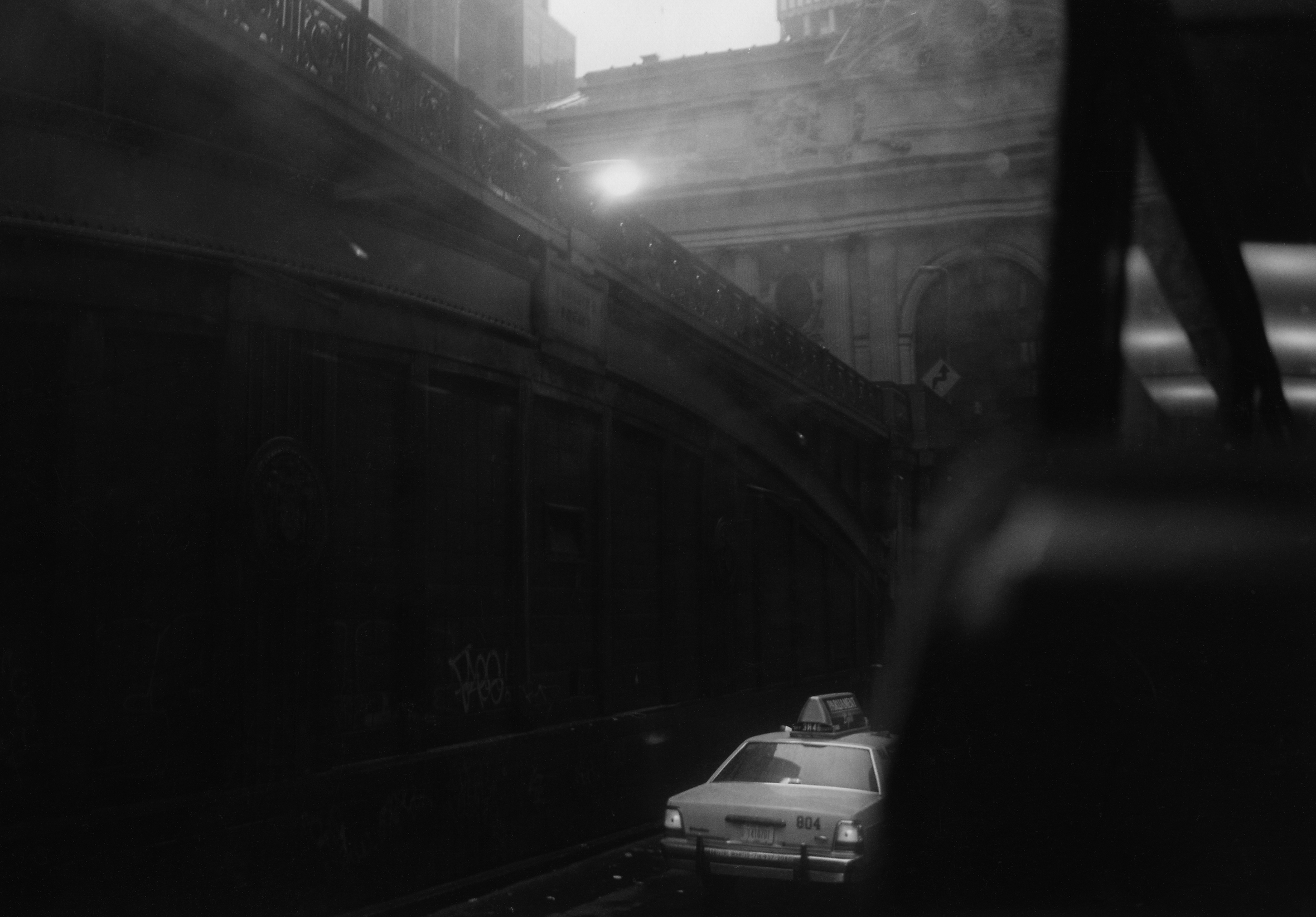

Soon Matt’s half-finished bottles of Coke are cluttering my kitchen table; his backpack lies belly-up on my couch. We take the PATH train from Hoboken to Manhattan and back again at night. For a thirty-three-year-old, Matt lives a little manically, and it’s like I’m in college again: Well whiskey at last call. Cigarettes arced out of cab windows to bounce and skid across the street like shooting stars. He DJs in nightclubs and basement bars, and I stand by myself in corners, sipping watery gin and tonics. I like not having to talk to anyone, because I’m not exactly there alone. And when he’s up there in the DJ booth, Matt doesn’t notice me at all. I am relieved of the pressure of his gaze, which is both suffocating and alluring. Afterward we walk hand in hand down the humid streets, in happy alliance with every drunk and vagrant we meet, tolerant even of the rats that skitter at the corner of our vision. Before my hearing adjusts, the entire city seems softer and cocooned. I feel like a leading character, too.

Weeks pass, and he’s still staying at my apartment, taking anthologies of plays off my bookshelf and reading them in the bathroom. I find them on top of the toilet tank after he’s gone to work. This is his way of burrowing into me. He says he wants to speak my language. “You resist things,” he says. “Usually good things. I want to know why. I want to get it out of you.”

In his wallet Matt keeps a photo of his parents and sister in front of the family farm in northern Michigan. They look hale and happy, like people who drink milk from cows they own—who drink both orange juice and milk at breakfast. This wholesomeness has followed Matt to the East Coast, despite whatever bad habits he’s picked up along the way: smoking, staying out late, mild delusions of grandeur. He is still a person used to walking outside in the morning and seeing a field that is his to tromp on; who expects a harvest each year. I wasn’t raised that way. I skipped breakfast as a child and arrived at school wearing my skepticism like a cloak. My mother is a fading beauty queen from Maryland, prone to headaches and fond of daytime TV. My father and brother are mole-eyed men, hard workers who continually get passed over for promotions. I don’t trust Matt’s easy, expectant attitude. To live like he does is begging for disaster. It’s disconnected from reality. But there is also a part of me that wants to see what he sees, that believes a life with him could make me, if not wholesome, then some other kind of whole.

“Don’t get me wrong,” I say, after describing my parents to him. “I love my family. They’re good people. My parents would do anything for me, literally anything.”

“I can’t wait to meet them,” Matt says.

What an uncomfortable dinner that would be. My parents aren’t good at small talk, which is part of what I love about them. After college I lived with them in Albany and took the bus to the city once every couple of weeks to visit friends. I felt desperate to get out of the house, but on the way back I couldn’t wait to get home. I remember sitting at the bus depot, waiting for my connection, dreaming about eating dinner in silence, no sound but the ticking clock in the living room. We didn’t need to talk.

Later that week Matt and I are walking down the hallway of his friend’s apartment building in Bed-Stuy when he grabs my wrists and pulls me toward him.

“Hey,” he says, a little drunk. “I want to tell you something. I don’t like it when we’re not touching. Never stop touching me. Not when we’re in the hall, not when we’re on the street, not when we’re in bed. OK? At least one body part on me at all times.”

Sometimes, when he’s needy like this, it’s flattering. But right now disgust comes over me, and I remember the way I felt about him the first time I saw him walking into the Shriveled Gun: the condescension and vicarious embarrassment. I try to twist flirtatiously from his grip, but he holds tighter.

“Stop,” I say.

“Say OK.”

“Stop. I mean it.”

He is smiling.

“Stop!”

I’ve yelled loudly enough to be heard down the hallway, and still he doesn’t let go. My arms hurt from fighting him. My sudden lack of strength is humiliating.

“You think this is funny?” I say in a low voice. “You’re disgusting. Keep your hands off me.”

It isn’t until I spit in his face that he finally lets go. His jaw hangs open in surprise, and my saliva on his chin looks like a badly healed scar. In that moment I want him to hit me. Or, if not that, then to show me a side of him that’s more complicated than the surprised, wounded look he’s wearing. Even a hint of fear would be better. I fell for him because he seemed too good to be true, but now his pureness is the thing keeping us apart. If only he had something wrong with him, maybe he could be my match.

“Don’t touch me,” I say, though he hasn’t moved. I remove a piece of string stuck to my shirt, watch it land on the floor. “Don’t fucking touch me unless I say so.”

I’m unsure whether I’m waiting for an apology or an accusation, but I want things to come to a head. They are too confusing as is. My body has become more his than mine. After we fight, there is always the urge to close the space between us, to go to bed and curl into him: head to neck, shin to shin, toes hooked around each other’s toes. I can turn my mind from him but not my body.

I watch his feet inch toward mine until the rubber tips of his sneakers meet the front edges of my sandals. The way he clings to me is both repellent and reassuring. Maybe this relentlessness is what was missing in the other men I’ve dated.

When I don’t move away, he leans forward and takes my wrists again, but gently. A security camera in the corridor is getting everything: his heavy breathing, his hurt, his hands around mine. He might appear predatory from that angle, but looking into his face is like walking into someone’s childhood bedroom: the innocence, the comfort. Why is my first impulse always to light the room on fire?

When I find out I’m pregnant, I don’t tell Matt. I tell Lauren instead.

“You’re not going to have it, are you?” she asks. We are at the Shriveled Gun again. I can’t remember the last time I walked into a bar without Matt.

“No.”

“Oh my God,” she says. “You’re totally going to have it.”

I stare at my paper napkin stuck to the bar’s surface.

“You’re not going to do it alone, are you? Did you know that most women find being a single mother harder than kicking a drug addiction?”

“No—what? That can’t be right.”

“I know what this is,” Lauren says, shaking her head. “He’s rubbing off on you. This is exactly the kind of idealistic, romantic bullshit Matt would pull.”

“Yeah, except Matt would want to get married.”

“Which would make him far more reasonable than you.”

“A baby is not a reason to get married.”

“You’ve got it backwards,” Lauren says. “A baby is probably the only reason to get married.”

The bar has gotten busy, and a man squeezes between us to place his order. When he steps back out again, Lauren is staring fixedly at me with a sad expression.

“How unoriginal,” she says, shaking her head. “This is, like, the most played-out situation ever.”

When I was in college, a professor once drew the shape of dramatic structure on a chalkboard. It looked like a bell curve: the setup, the slow build, the climax, the falling action, the denouement. The shape of it never changes, he said, only the circumstance and the characters. Maybe the shape of my life story was imprinted on me by years of studying theater. Or maybe I’m just more predictable than I’d like to admit.

I feel like Matt knows I’m pregnant even though I haven’t told him. I wake up in the morning to find not only his arms around me but his hands cupped around mine, as if to steady me in my walk toward motherhood.

I think about the word womb a lot, about how it sounds like a cross between wound and tomb. I don’t want to be a mother. I am not qualified to be a mother. Whenever I’ve imagined my future, I have seen myself grown into old age alone but fulfilled. I’ll live in a tiny but nice-enough apartment, exchanging cordial greetings with the doormen downstairs. I’ll continue working at the bank until I retire, see as much theater as I can, write about it as long as I can, maybe take on a young protégé or two. That would be enough of a social contribution to allow me a graceful exit from this world. To raise children—to coddle and love them, to risk finding myself sitting by the phone in my eighties, waiting for them to call—would be melodramatic.

I take the L train to the clinic on 14th Street. I have not eaten dinner the night before, as instructed. The lightheadedness is a good distraction from my anxiety. But, when the time comes, I can’t rise from the maroon pleather chair in the waiting room. “I’m not ready yet,” I tell the nurse. “I’ll go after the next person.”

I stay long enough to see three women go in and come out. As they leave, I try to detect some change in them—these mothers who’ve been unmade—but can’t. I pace the waiting room and the hallway outside. My mind wants to leave, but every time I press the button for the elevator, my feet take me elsewhere.

Maybe I can’t think because I’m so hungry. I stuff quarters into a vending machine in the hallway. Ten minutes later I’m coughing up a wet mush of Nilla wafers into the toilet in the clinic’s handicap bathroom. I breathe, flush, and just sit there on the floor for a minute. There’s an anti-smoking-campaign poster taped next to the mirror over the sink. On it is a diagram of the human body and a close-up of a pair of disintegrating lungs. The whole thing seems to me like a congested mess. I’m not sure why all these body parts are necessary. What is everything for?

That night I decide to tell Matt I’m pregnant. I sit him down at the kitchen table because it feels less intimate than the bedroom. “There’s something I have to tell you,” I start, in the spirit of unoriginality. When I’m done explaining and finally look up at him, there is a dull cast over his face. For a long time he says nothing. The kitchen is silent except for the hum of the refrigerator.

“I knew it,” he says. “You smell different. You taste different. And you never want to go out anymore. How could you not tell me? It’s half mine.”

Then he begins to cry. He should not be the one crying. If anyone should be crying, it’s me. And yet I’m relieved to see his tears. Because if he’s crying, that means I get to be the one who steers us straight.

“I didn’t tell you,” I say placidly, “because what was happening between me and you is one thing. What’s happening between me and this thing inside me—that’s something else.”

“What the fuck is that supposed to mean?” he asks. And then, a moment later, “What do you mean ‘was’?”

“What?”

“You said, ‘what was happening between me and you.’ ”

And there it is, the facial expression I was looking for that day in the hallway when I spat in his face: fear. For the first time we are feeling the same emotion together, and for a moment it brings me closer to him.

“I just mean that this is a decision I’ve made on my own,” I tell him. “So I don’t think you should be responsible for it. We should talk about how this affects our relationship, whether we should stay together or not.”

“You’re telling me you’re going to have this baby,” he says. “And it’s mine. So isn’t it our baby?”

But something slightly cold in his face suggests he doesn’t want the baby. Or he doesn’t want it with me. He looks away from me and speaks into his hands. “What are you going to do, anyway, bring a kid up by yourself?”

I realize he wants me to say, Yes, that’s exactly what I’ll do. Then he can wiggle away guilt-free. I don’t answer, and he doesn’t ask any more questions. But the longer he says nothing, the more I find myself hoping he will say something he said to me on our first date: We’re meant for each other. I don’t know why I know it, but I know it.

I am waiting to see what he will do. His romantic ideals—will they really hold? How much of his life is he ready to give to me? How much of him do I already own? I don’t know much about love and relationships, but I do know that one person always loves the other more. Either you own somebody, or they own you. You’re either the mouse or the trap.

“Hey, hey, take it easy,” he says. Only then do I realize I am wailing loudly enough to alarm the neighbors. He has never seen me cry before, and he gathers me jerkily into his arms. “Let’s go to bed. We’ll talk about it more in the morning.”

I let him lead me into the bedroom, where we curl up and spoon. Before I fall asleep, I decide I’ll make him leave in the morning. It’s because he’s here all the time that I’ve lost track of myself, that I’ve made the stupid decision not to go through with the abortion. It’s only because of him that I’ve begun to want things that are not for me to have.

The next day I wake up to the smell of pancakes. Matt is in the kitchen whistling and licking batter from his fingers. He seats me at the table and feeds me the first bite: gooey, warm, and sweet. Afterward we take a walk. The trees are in bloom, and the smell of flowers is heady and strong, but miraculously I don’t have to puke. It’s Saturday, there’s a street fair, and we come home wearing funny hats that make it hard to talk about serious things. By evening we are queasy from funnel cakes, and we watch comedy specials on TV and laugh. I think about how, without him there, the apartment would be silent. I am not in charge, I realize. Each day he stays means greater disaster if he leaves. “Hey,” I say, looking up at him. “Wanna get married?”

On a rainy day in March we ride the subway to City Hall. He’s in a tux and sneakers because he forgot to rent the shoes. “You said no pictures, anyway,” he says, grinning with pure joy. I think I imagined his reluctance the night I told him about the baby, the night we decided on the direction of the rest of our lives. In front of the officiant his eyes are clear and shining.

Matt gives up his more-expensive apartment in the city and moves in with me. My windowless home office will be turned into a nursery, and he’ll keep his DJ equipment in a Manhattan Mini Storage downtown, where he’ll retrieve it before every show. But soon there are fewer shows, fewer trips to Manhattan. He settles into the apartment in a way he never did before. When the sun sets, he goes from room to room, turning on every light. He twists the wedding ring around his finger as if trying to get a better fit, become a better husband. And because he wills it, he does. Forget husband—a few months in he’s become dad-like. He trades sound samples for paint samples, DJ gigs for books on software development. In the glow of the computer screen, he presses his glasses closer to his face, his eyelashes batting the lenses. Is this the person I fell in love with? Maybe not, but it’s possible that I love him more now that he has lost the spark that once made him seem alien. He’s like me now: a little worn. Soon the two of us will move farther into New Jersey and buy a car, and he will eventually find more pleasure in its parts than in mine. He’ll get grimy fixing it on Saturdays. Drink in moderation. Give up trying to stand out. And he’ll worry—as I do—that the exciting climax of his life has already happened. Here is the ending I’ve been anticipating; here is the ending I knew would come.

One night, doing research for a review, I come across a Wikipedia entry on shipwrecks. “Listen to this,” I say to him. “This is so weird. They have different names for the crap floating in the sea. If it’s debris from an actual wreck, they call it ‘flotsam.’ If they tossed it overboard to get rid of dead weight, it’s ‘jetsam.’ If it’s sitting at the bottom of the ocean but has the possibility of being reclaimed, it’s called ‘lagan.’ And if it’s at the bottom of the sea but there’s no hope of it ever being reclaimed, it’s called ‘derelict.’ Isn’t that kind of poetic?”

He is painting the living room and has ordered me to stay in the bedroom until he’s finished. “Can you get out of here?” he asks when he sees I have left my designated area. “Fumes,” he says, pointing to the wall. “Baby,” he says, pointing to my stomach.

I laugh. “You smoke a pack a day, and you want to worry about paint fumes?”

He looks as though I’ve slapped him. “I only smoke outside now,” he says in a small voice. “And I’ve cut back.” Suddenly I am ashamed. He has been trying so hard. It’s not just his voice that’s grown small; his whole being feels cramped. All because I let him love me. And he doesn’t see it. He can move out of the city, we can change our bodies and our habits, but we can’t change who we are. The types of shipwreck are not interesting to him and never will be. He is not interested in the distinctions between types of ruin. And how like me to romanticize a shipwreck, to find poetry in the naming of things that are lost.

Eight months pregnant, I wake one morning to a realization: If my fatal flaw is avoidance, then Matt’s is that he knows no option but to go forward. Because of who he is, he will never be able to leave this life he hasn’t chosen. It’s up to me to leave him.

To raise this baby by myself will be hard, but I know my parents will take me in. And, in a way, the baby will make up for my having turned out to be a different person from the one they expected. They had imagined someone a little more traditional, more obvious in her desires. What’s more obvious than a baby?

Beside me, Matt is still asleep. His arm is draped across my neck, and when I slide out from under it, he turns over, shirt twisted up to expose his lower back. I take a last look at him and leave the bedroom. We keep an overnight bag near the door for when I go into labor. I shoulder it and look behind me: the early-winter light illuminates the dirt clouding the living-room window. Matt was going to clean it this weekend, but with me gone, maybe he won’t.

I memorize the shapes of the neighboring buildings on Monroe Street as I wait for my car to arrive. One day I will look back on this moment from the context of another life. When the driver arrives, I ask him to take me to the Port Authority. The bill comes to almost fifty dollars—a small sum, all things considered. It’s difficult to move with a stomach this big, but each step I take also feels like a load off.

At the Port Authority I have to wait an hour to board my bus to Albany. By now Matt has probably woken up and found me missing. He has seen the empty spot next to the door where my bag once was and realized what I have done. I think about turning my phone on to call him—he deserves that, at the very least—but I decide not to until I’m on the bus. That way I cannot consider turning around.

I buy a cup of coffee and use the restroom for the third time this morning. In the mirror my face looks like an irritable child’s; the skin is puffy, as if I have just woken from a dream. A woman enters carrying packages wrapped in holiday paper, and I remember, with some embarrassment, that I will be showing up at my parents’ house empty-handed, carrying only the baby in my belly. I hope we will be welcomed like a gift.

I come out of the restroom and head back toward the waiting area, and as soon as the benches come into view, I feel my heart slam into the wall of my chest.

There he is, waiting for me. Matt. Still wearing that nubby T-shirt underneath his dirty white winter jacket with a hole burned in one sleeve where it strayed too close to a cigarette. For a moment he appears to me as he did that first night we met—with his artist’s dinginess and his skinny slouch. Then he sees me. He doesn’t stand. There is no reproach on his face, just weariness. He watches me with mild interest, the way a homeowner might watch a small animal moving across his lawn.

My mouth is dry, and my back is aching. I want to sit down beside him, but my body will not do what I tell it to.

“We don’t even know each other. Not really,” I say.

“I knew you well enough to find you here.” He rubs his chin slowly. “I’m not going to force you to come home. Your bus boards soon. I’ll watch you get on it, if that’s what you want.”

How did I get here? It must be the baby. The baby has had an unexpected power over my decisions. Over the past eight months I have become used to it telling me what to eat, what to wear, how to arrange my body in bed at night. My belly precedes me everywhere I go, as if I am following the baby around. How ridiculous of me to have put myself in this position, when I have such trouble ceding control. Here I am, pregnant, the punch line to every story about a woman ever told. A part of me must have willed it, no matter how badly cast Matt and I are in these roles.

Once, years ago, after seeing a friend’s play, I was invited to the cast party, where I talked to the lead actor.

“It must be nice entering the same story night after night,” I said.

“Nice?” she asked.

“You always know what’s going to happen. You get all the excitement of drama without the surprises.”

“Oh, that’s not how it feels at all.” She laughed. “When you’re out there, when things are going well, it feels like anything could happen.”

I’ve been telling myself I left for his sake, but I’m no longer sure that’s true. I imagine getting on the bus, the confetti-patterned upholstery of the seats, my head vibrating against the windowpane as we make our way upstate. Early evening: my parents standing in the doorway of their house, their shadows leaping out to greet me as I approach. But that’s as far as I get. I cannot imagine what my body will feel like lying in bed alone tonight. I cannot imagine labor. I cannot imagine the years ahead. There has always been an impulse in me to hasten to the finish, to rush toward disappointment rather than be flung out of shape by hope. But I can’t picture the end of this.

Once, Matt looked at me like I was the moon. It was an easy part to play; coldness and distance were what I already knew. He doesn’t look at me that way anymore. Maybe reality has set in, and maybe exhaustion has, too. What comes after hope and fear have gone? If the answer can be found in his expression, it must be a kind of stillness. It’s like a hush has fallen, the kind that precedes a curtain rising. He is waiting to see what I will do.

Overhead a speaker announces arrivals and departures. I wonder which we are experiencing now and if it’s possible to be both. In the end, maybe it doesn’t matter what I call it. Both require forward motion. So I find the strength to move.