It started with a line from the writings of Norman O. Brown: “Everything is only a metaphor; there is only poetry.” It seemed to say it all. It was the one reminder I wanted on my wall.

I don’t remember what I put up next. Probably the quotation from Ram Dass. (“I do crummy things. I do beautiful things. Does that mean I’m good or I’m evil? I’m neither. I just am.”) Or the picture of my children. Soon, there were those wonderful lines from Tagore. And Auden. And Rilke. And Kerouac’s instructions to writers. (“Accept loss forever. . . . No fear or shame in the dignity of yr experience. . . .”) The photo of me and Jimmy, his roguish smile, his arm around my shoulder, and next to it his poem, about feelings “like valleys ending in each other” and words about feelings “like a small underground creek.” And the extraordinary portrait of John Lennon, taken just days before he was killed, his eyes seemingly dark with the secret, the last surprise life was waiting to spring.

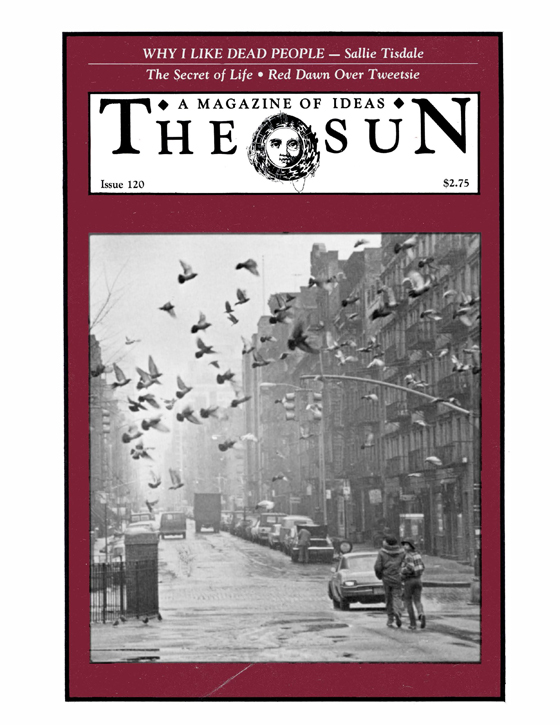

There, beside my desk, the words and pictures edged to the left and to the right, like a city pushing into the countryside, and up toward the ceiling and down toward the floor, until the cracked plaster and peeling paint were almost entirely covered, paved over. I’d never cared for the starkness, the menacing emptiness of bare walls. “Sy’s wall,” my friends called it. Occasionally, one of them would step around my desk for a better look. After all, this was the graffiti of my inner life. If you knew what to look for, you’d see whole histories reflected: in the snippet of conversation with my landlord (“You can’t pay your bills and you’re happy,” he said. “I pay mine and I’m miserable. I don’t know — who’s got the better life?”); in E.B. White’s description of New Yorker editor Harold Ross’s “simple dream: it was pure and had no frills: he wanted the magazine to be good, to be funny, to be fair” and in pursuit of this pure and simple vision, he “spent himself recklessly on each succeeding issue, and with unabating discontent;” in Thomas Crowe’s haunting summons: “I am through with my love of suffering and the words that describe that love.” And there were my pin-ups: Gandhi and Thomas Merton and that old Indian saint, Neem Karoli, who peered at me from beneath bushy eyebrows, his loving scowl skeptical of everything I advertised as love, these inspirations, this wall of longings, this wailing wall — for isn’t what we strive for precisely what we think we lack?

Ironically, I rarely looked at what I’d put up. Sometimes, during a boring telephone conversation, my eyes would wander to some quotation; at the end of the day, on the way out the door, I might read a familiar line and pause. But for the most part, as soon as I came across something worth remembering, and tacked it up, the thrill of discovery began to wane, the moment of revelation became a memory, the unfamiliar phrase became one more familiar thing on the wall, taken as much for granted as the birds and the traffic outside, the sunlight slanting through the blinds. To take life for granted is natural and regrettable, which is why we put up reminders not to take life for granted, and ignore them.

Last Christmas, we painted the office for the first time in years, and I had to take everything off my wall. I didn’t want to do it, because I knew it would force me to consider each quotation and picture, and decide which ones I wanted to put up again when the painting was finished. I was rarely in the mood for such soul-searching after a long day at my desk, so I kept putting it off, until the very last night, when I had to roll up the rug and move the furniture into the hall. Alone in my office, in the empty room that echoed me back to me, my hands undid what my hands had done. But how was I to judge which things I wanted to save — which were living reminders of truth and which were reminders, instead, of what was dead and gone? Perhaps truth remains the same, but we change: what yesterday we insisted was ice, today we’ll swear is steam. That photograph of me and Ram Dass on my front porch: all I saw in it now was me mugging for the camera, posing with the President, confusing celebrity-fucking with love. No, no, I tell myself, that’s too harsh: it’s because of what Ram Dass taught me about love that I cherish him, not because he’s a celebrity. But is that true, really? How utterly untrustworthy I am when it comes to “love.” The word itself is a whore, bedding down for the night with whoever is willing to pay: Mr. Ego cruising after dark in his Cadillac of higher ambition; Mr. Prince-Of-A-Guy, who sucks the life out of mirrors checking his style. But it’s nothing personal, it’s the way we’re built, with these minds willing to betray the heart’s greatest sacrifice for a little smile, a little cash. Or have you never heard yourself trading on the best of what you’ve done, imagining that you were only drawing on the interest, and leaving the balance of yourself intact? Isn’t Ram Dass himself so endearing because he’s honest about his pride, the fast deals he made in the corridors of spiritual power, his lusts, his crooked smile? So what’s wrong with keeping his smile before me?

Or Patricia Sun’s smile, she of the perfect teachings and perfect teeth: how much better blondes look in the Light! She’s up there to remind me about forgiveness, but can I forgive myself the reminder she’s sexy, too, which makes what she says a tad more compelling? How I love the naked truth. . . .

On through the night, photograph by photograph, quotation by quotation, my wall came down; memories came undone; like the mind uncoiling from itself as it drifts to sleep, the images on my wall one by one trailed away and disappeared, leaving behind what was always there: cracked plaster, peeling paint, emptiness. Oddly, I no longer found the emptiness menacing. Indeed, a couple of days later, covered with a fresh coat of paint, the bare walls in my office suddenly seemed to speak for themselves, not in words or pictures, not in the language of Truth, not “about” anything, but in a way that was strangely compelling. I recalled how, along with my friends, I had once derided the white-on-white canvases of avant-garde artists; yet here I was, loathe to put a single thing back on my white walls. None of the teachers, none of the teachings, made quite as much sense anymore as their absence did!

Nearly a year later, my wall is still bare. In a sense, I’ve replaced fifty different reminders with one. It can’t be put into words, although there are fifty different ways to try. Here’s one way: if life is the teacher, who needs teachers? If I live my life truthfully, why should I need to follow the crumbs of truth others have left?

But how hard it is — how much more subtle and demanding than what I do or don’t put on a wall, or say to a friend, or write in a magazine — to make my own way, free of spiritual conceit. No wonder my harshest judgment falls on those I imagine to be even more conceited than I! My compassion fans out in loving waves to the deluded racist, the mass murderer, the bum who lies to my face, but for the new age con artist or the zealous devotee of a phony guru I have nothing but ridicule and for the so-called master himself, contempt.

A couple of years ago, it was reported that Swami Muktananda, one of the most respected meditation masters to have come to America from India, and an avowed celibate, had been having sex regularly with his teenaged disciples, and threatening with bodily harm anyone who complained about it — as well as amassing a small personal fortune in a Swiss account. About the same time, Richard Baker, one of the foremost Zen Buddhist teachers in America, became embroiled in a scandal about his sexual conduct. More recently, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, the Indian sage who owns thirty Rolls Royces, ended a four-year silence; in his first speech, he denounced his chief spokeswoman and other top followers in a controversy involving charges of murder and blackmail.

In the history books, I doubt whether these stories will even rank a footnote, yet for me they’ve been meaningful, nearly as compelling as news about my own family. For what is news, really, but something by which we take our own measure, or see another revealed; the rest is endless embroidery of an old design, ragged and faded, which barely holds your interest, nor should it. Journalists write the stuff because they’re paid to, and people read it because they’re so bored with their own lives it’s a relief to be distracted. But when something in the press speaks to me, acknowledging real human struggle, going beyond the facile abstractions about “society” to what society really is — you and me and the people we know all too well, our passions and fears and betrayals, the tangled politics of our lives, our yearning for deeper understanding and the wars we fight on the way there, the heart’s wordless cry — well, this is family, this is news, and each time I’d read of a fallen teacher, my face grew stern, my heart grew hard.

There was no question in my mind but that Muktananda and Baker and Rajneesh were extraordinarily wise beings, as knowledgeable about the nature of reality and the secrets of the soul as you are about what’s in your pocket. I mean, they’ve been places most of us haven’t; to deny that would be as foolish as insisting that some exotic island halfway around the world, which you’d never seen and weren’t likely to, for that reason didn’t exist. Some people devote their lives to becoming wealthy, and end up multi-millionaires; others devote their lives to spiritual study, and end up rich in understanding. There’s nothing particularly mystical about it: there are religions that enshroud spiritual laws in secrecy, but they’re secrets only until you figure them out. Many of us do, but we lack the commitment or energy to apply ourselves to the task full-time, so our knowledge is fragmentary and unreliable, and we swing from moments of enlightenment to moments of utter confusion. But to live this way is a choice, and some make a different choice.

To seek truth so earnestly that nothing else matters — sex, money, status — is hard for most of us to imagine, yet the biographies of the great teachers suggest great sacrifice, and are offered as inspiration to the rest of us, who hear the summons but stand silently by the window, watching our destiny like a great dark cloud rush by. Driven by the winds of compromise and practicality, we assure ourselves that travelling to work in the morning is a kind of meditation even if we haven’t taken the time to sit, and that a simpler life would be better, but there are these bills. And this ache each night, this ache we’ve learned isn’t for a lover or a snack or a pill — what else is there? What are we aching for? And one day we find ourselves staring at the words of a Muktananda or a Rajneesh, and we are reminded of what else there is; the arrow of our longing flies straight to its target, reminding us, as it hits, that the heart longs only for God; and we are reminded, too, that in the pure seeking of another, we can see ourselves reflected, and are grateful.

To discover that the words are only words; that the holy pictures are double-exposures; that the guru’s nut-brown hands raised heavenward in the morning are at night busily undoing a fifteen-year-old’s bra — all this is somehow harder to stomach than the deceit of a politician, who after all promises only heaven on earth, or the more forgivable trespasses of a wife or a friend, because we know their love is haunted, as ours is, as everyone’s is, even, it turns out, these lovers of God, these sinners in drag as saints. Or is it the other way around? Some followers insist the crime is in the eye of the beholder, that the guru is just giving us another lesson in attachment, showing us how quick we are to judge. I find this reasoning intellectually plausible, but my intuition says it’s wishful thinking. Seeing your parents or your lover or your guru fall from grace hurts, and it’s tempting to pretend your eyes, and not your beloved, deceived you.

To those less able to deny the pain of betrayal, it’s all one can do to keep from closing the door not just on fake saints but on the very idea of saintliness, not just on bargain-basement godliness but on God, too. This is one reason I shudder when I hear THE SUN described as a “new age” magazine or myself as “spiritual.” No thanks. If these pages bring you a little closer to the truth of yourself, that makes me happy, but if I let myself capitalize on that in the slightest — and I’m not even talking about getting laid or getting rich, but something subtler — then God is driven yet farther away.

Still, I knew that my anger toward people like Muktananda was keeping me from understanding something important — anger always does — and it wasn’t until I read a letter recently from a SUN subscriber, who had followed and then disavowed Muktananda, that I realized what it was.

In his letter, Marc Polonsky referred to the days before Muktananda came to America, to a younger Muktananda who did not want to be drawn into the world, did not want disciples, told everyone he was a renunciate and a loner. But more and more people came anyway.

Marc suggested that Muktananda had, in fact, attained great spiritual power and “had wisely been afraid of being tempted by the world, by wealth and sex and emulation,” and “had ultimately fallen to the lowest in himself just as he had feared, giving and giving until there was nothing left to give.”

“What terror he must have endured. I feel he is probably deserving of our pity and compassion.”

It was so obvious a conclusion, yet revelatory for me. Instead of reacting to Muktananda and my other fallen heroes as if their arrogance and dishonesty were a personal insult to me, as if — simply because they set themselves up as saints — I had every right to expect saintliness from them, I could instead remember that they were as deserving of forgiveness as anyone, that if their power was greater so were their imperfections. Who can say what dark angels they wrestled with?

I realized, too, what a golden opportunity America presents to these Eastern holy men to succumb to the temptations of fame and wealth. For surely this society, materialistically magnificent, is a twin mirror to the spiritually rich East. Having mastered the inner realms, these would-be saints get the chance to endure the American stations of the cross: instant celebrity, computerized miracles, California girls. Our affluence is as exquisite a challenge for them as a suffocatingly hot hotel room in Benares would be for a businessman from Milwaukee setting off to find his guru.

Of course, it may be that we only hear about one type of teacher. Back in the Sixties, the more successful communes knew better than to give themselves a name and I suspect that a similar wisdom may prevail among God’s truest servants.

Again and again, I’m struck by the consequences of mythologizing someone else’s power, whether a guru or a President or a beautiful stranger. To respect someone is one thing; to raise them up on a pedestal merely shows me how deep a hole I’ve dug for myself. Making myself lower than another isn’t a sign of humility; rather, it’s an insidious kind of pride, in which I bow before my real or imagined weaknesses, making them the sum of me. I think true humility lies in accepting not just our frailty and corruptibility, but accepting as well our real power, the love which allows us to forgive ourselves for being so perplexingly human, and to forgive the next guy for pretending he’s any less perplexing than we are.

— Sy