When I have a problem, I sometimes have difficulty owning up to it. It’s much easier to say, “He’s screwed up to get in my way like that,” or “How can they treat me that way?” And this only intensifies my problem. I alienate myself from others and at the same time allow my head (intellect) to separate itself from my guts (feelings).

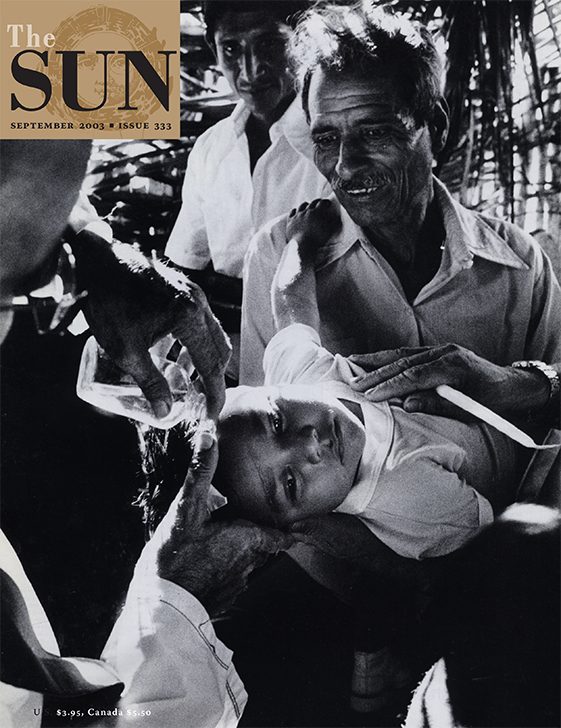

I now realize that to cut through the games I play when I’m in a problem time, I have to practice. There are skills I can learn to get back in touch with what should come naturally to me as a human being. Just as many friends practice “natural” childbirth so that the birth process will flow as smoothly as possible, I practice communication skills so that when the need arises I can be in touch with and share my true thoughts and feelings.

For example, I am often afraid to confront someone when her behavior is causing me a problem. She may get angry, laugh at me, ignore me, fire me, feel hurt or offended, or not care to associate with me again. I’ve had all of these responses and they helped teach me to keep my mouth shut. But then by not confronting I would start to accumulate bad feelings towards that person. Other problems would occur: I would deny I had needs, I’d feel frustrated and impotent or I’d use indirect or manipulative techniques to avoid any confrontation (like driving three or four blocks out of my way every day to avoid passing her house, for fear she’d wave me down).

My goal (successful confrontation) is (1) to deal with the other person’s behavior, when it occurs and causes me a problem, in a way that will increase the chance of getting his cooperation; (2) to share my thoughts and feelings in such a way that I don’t attack his self-esteem (this may help to focus his energy toward helping me, rather than reacting against me); and (3) to construct a message about where I’m at that will do minimal damage to the relationship. I must also be willing to do things that will maintain or even enhance the relationship, such as being sensitive to her reaction to my message, helping her handle any problems my message causes, and being willing to risk sharing my true feelings with her.

So, when someone is causing me a problem and I want to modify his behavior, I choose an approach which is effective at producing helpful change; has a low risk of lowering the other’s self-esteem, and has a low risk of hurting the relationship.

The approaches I would typically take failed to meet these criteria. For example, if . . .

a. my friend owed me $85 and hadn’t paid up after two years,

b. my parents called to invite me to their home for Christmas, or

c. my lover decided to go off the pill and try “natural” birth control.

. . . my typical response might be one of the following:

A. Solution Message (order, threat, promise, moralize, teach, advise)

“If you want to keep your friends, I’d suggest you not keep yourself in debt to them for too long.”

“Hey, get off my back, will ya’. I was home for my birthday in ’73 and I promise I’ll be down in Charlotte sometime next spring.”

“Ain’t no way we’re gonna put it together unless you stay on the Pill.”

B. Put-down Message (criticizing, blaming, name-calling, analyzing, questions, probing)

“O.K., asshole, I’ve had enough of your dependency shit. Pay up.”

“You’re just lonely because you don’t know how to get out of that nurturing parent role. I’m not playing that game.”

“You’re out of your mind. I have this sense you’re ready to settle down and have a family, and this is your trick to get it all started.”

C. Indirect Message (ignoring, kidding, sarcasm)

“I hear the loan shark business is mighty profitable these days.”

“Of course I’ll be home. Just like always.”

“Speaking of birth control, did you hear what the Maharishi said when someone called TM the McDonald’s of Meditation?”

I began to see more clearly why these types of messages were ineffective. My Solution Messages would cause resistance, for most people don’t appreciate being told what to do. They think that I think that they are too dumb to figure things out. My Put-down Messages chipped away at their self-esteem, caused them to lose face, argue. Often people didn’t catch on to my Indirect Messages (usually coming in the form of desert-dry humor). If they did, it taught them that I was not open, but sneaky. Basically, these messages don’t meet the three criteria.

So, what’s my alternative? My major change is replacing the emphasis on the other person (the pronoun “you”) with sharing what’s inside me (the pronoun, “I”). It describes me, not the other and therefore might produce less defensiveness; it tells the effect of the other’s behavior on me, which provides data instead of blame; it helps me focus on my feelings about the effects on me instead of my feelings toward him.

The other person can then change his own behavior, not because he was forced to, or out of guilt (being the “bad guy”), but out of consideration of my needs (feeling more like a “good guy”).

There are all kinds of “I-messages.” When I’m having a problem with someone else’s behavior, I hope my message to him will express my feelings or emotions, a non-blameful description of his behavior, and the tangible effects of his behavior on me now or in the future.

Let’s go back to those three cases.

To my friend I might say: “I’ve got an expensive trip coming up, and I’m really low on cash [effects]. I’m afraid that without some more money I won’t be able to go [feelings]. I know you’re not working much [behavior] so I’m hesitant to ask you for any [feelings]. But after two years of promises to pay me [behavior], I’m starting to feel used [feelings].”

I might talk with my parents a half-hour about our conflict, but if I were to share my feelings concisely, it would be: “I appreciate [feelings] your asking me home [behavior] but I’m really feeling stuck [feelings]. I love Christmas Day with the family [feelings] but this vacation time is the only chance I have to ski in Colorado. When you continually ask me to be home this Christmas [behavior] I begin feeling guilty and resentful [feelings] because I can’t please you and go where I really want to go at the same time [effects].”

To my lover, it might go like this: “I’m afraid when you say you might go off the pill because I don’t want to be a father.”

A simple model for constructing such a sentence is: “I’m (your feeling) when you (her behavior) because (consequences to you).”

Make sure that description of her behavior is as non-blameful as possible (not “. . . when you always nag me . . .”).

O.K. Now I’ve sent my message. What happens next? What if I don’t get what I want? What if they become defensive?

Often people will be resistant. What do you do? Listen to them. Hear what they have to say. You’re in a relationship; they are the other half. Find out what’s going on over on that side. Hang in there for your needs, but don’t walk on top of your friends.

By blaming my friends when I have a problem (trying to say they own the problem), by telling them what to do, or by avoiding any direct confrontation with them, I continue to alienate myself. My friends avoid or resent me and tend to treat me more as an object than a human being. My relationships lose their energy, and I stop asking for help when I’m in trouble.

By sharing who I am, how I feel and how someone else’s behavior fits into my life, my friends tend to treat me more as a lovable and capable human being, their self-esteem stays high, our relationships are healthy, and when I need help, I’m more likely to get it.