On a shelf in his bathroom, so high I need a stool to reach it, there’s a leather cuff link box where he keeps a pet spider. The spider eats matches. I know this because every night before I go to bed, my father shows me the match, puts it in the box with the spider, and closes the lid. Then, in the morning, he opens the box to show me that the match is gone. It doesn’t occur to me that this spider never moves when I look in the box. A spider can’t always be asleep.

Every Christmas Eve, it’s the same old question. “Who’s going to help me catch Santa Claus?” my father asks. “Who’ll help me grease the chimney?” Horrified, we shrink away.

“What’s wrong with you kids? Why, if you’d just help me catch the old man, you could have all those toys for yourselves.”

Later that night, as we lie in our beds, we hear sleigh bells on the roof, and the stomping of feet. In the morning, there are sooty footprints around the hearth, half a glass of milk, and cookies with bites out of them.

One year, desperate and still unassisted by these “weird” kids who can’t appreciate the fine art of Santa-trapping, my father rigs up a giant snare and hangs it across the front path leading to our house. On Christmas morning, the trap is sprung and one long, red stocking dangles from a rope.

When the barn on the old Chambers estate goes up for sale, my father pays $10,000 for it. We all think he’s crazy. The place is a shambles, and besides, why would we want to leave the comfortable brick house where we were born? But soon, our living room is in an old livery stable. A Ping-Pong table and television sit where cows were once milked. When it rains, we can smell the barnyard animals so distinctly that we can almost see their faces pressed up against the windows. We watch my father spend a summer painting scenes from the Civil War across the entire living room wall, and then, dissatisfied, cover it with pine paneling. Often, when I come home from school, I see hammers and saws. Knocking down a wall, putting up a ceiling, my father is rearranging rooms again.

In the living room of our barn home, an enormous picture window looks out onto a courtyard. My father sits there in his favorite chair, smoking. A haze of smoke floats in a layer across the living room. He sits there every morning until 10, smoking and drinking coffee in his bathrobe, daydreaming — “working,” actually — before he goes to the office to design more buildings for schools and prisons. Sometimes I sit with him in the smoky haze and listen to him explain the history of the world or give advice on how to get what you want in life. His talk can run on forever, and it feels like my sitting there is a gift to him. He needs someone to listen.

He’s in that favorite chair when I find him stone-still one afternoon. I am sure he is dead. Panicked, I sit and stare at him. I go upstairs and wring my hands and cry. What if he isn’t dead and I embarrass him by waking him up? What if he is dead — shouldn’t I be doing something? When I go back downstairs, his eyes are open and he’s at work on another cigarette.

My father tells us about having his eye shot out when he was twelve. A friend pelted him in the eye with a B.B. gun. One of his eyes does look different — quieter than the other, with less expression in it. Once, when I come home very, very late from a date with a boy my father does not like or trust, he confronts me in the hall outside my room. In his pajamas he stands there, his face red and steaming, one eye flashing, the other eye peaceful and benign. My father is too angry to speak, but that one eye says it all.

It is Easter Sunday, 1974. I am thirty-four years old, and my father is seventy-four. He’s been sick in bed since January, which is uncharacteristic of him. Since he refuses all but the most minimal visits from doctors, we don’t know much about what is wrong. It’s pneumonia, we think, as well as unhappiness about working in an office where younger men are now calling the shots. The physical problem is compounded by the fact that my father will not give up his Camels, no matter what.

I have come to bring him an Easter present. It’s a little man that my four-year-old daughter and I have made out of a blown egg — a mock image of my father, wearing a suit and bow tie, reading The New York Times. My father is too weak to pay much attention to it, so I sit on the bed and hold his hand. It’s a beautiful hand with long, slender fingers and smooth skin. I don’t remember ever holding his hand before, but somehow it seems natural to me now. In some part of myself, I understand that I will never see my father again.

Peyton Evans Budinger

New York, New York

He was sitting on the front porch when I got home. He hugged me with tears in his eyes. My mother told me that he had been sitting there all afternoon.

When people ask me what my father was like, I have to say I don’t know. I lived with him for twenty-one years, but we never had what I would call a conversation. He died three years after I moved away.

My sister tells me that when I was very young, my father was loving and affectionate with me. I have only a vague memory of sitting in his lap and giggling when he scratched my face with his beard. When I was about seven, something happened — I don’t know what. For some reason, he abandoned us emotionally and escaped into the lonely dark with alcohol.

My father was the oldest of thirteen children. His father, a sharecropper, beat him. Although he was physically abused, my father was gentle with us. He was not a handsome man, but he had the clearest blue eyes I’ve ever seen. After his death, a friend of his told me that as a young man my father was “the best dancer in the country” and used to call square dances. I never saw him dance.

My father had a sixth-grade education, and worked most of his life as a truck driver. In high school, I was an honor student in math. One night I had an algebra problem that I couldn’t solve, and I was totally frustrated. He was sober that night and asked to see the problem. He worked it within a few minutes — not in proper form, but correctly. Was he brilliant or is that my fantasy? If he was, what a tragedy that he never had the opportunity to express his intelligence. But even if he wasn’t, his life was still a tragedy.

Being the daughter of the town drunk was painful. I hated him for the shame and fear I lived with. I wanted him to go away. I resented my mother for not taking us away. He verbally abused my mother. He was a bigot and at one time, I suspect, a member of the Klan. I despised that about him.

I have two special memories of my father that I cling to. When I was sixteen, he took me to the woods to find a Christmas tree, because I didn’t want one from the Piggly Wiggly store. He borrowed a truck, and we drove in uncomfortable silence. We walked for miles to find the perfect tree. When I found it, he said it was too big. I insisted that it was exactly the right size. When we got it home, it was about two feet too tall and dwarfed the living room. He didn’t scold or say, “I told you so.” He just trimmed the tree.

The other memory is of my first trip home from college. He was sitting on the front porch when I got home. He hugged me with tears in his eyes. My mother told me that he had been sitting there all afternoon.

Brenda Pope McVay

Montgomery, Alabama

When I was fourteen, my father, kid brother, and I went on a rafting trip. After a couple of days, we stopped at a small town for lunch. Toward the end of the meal, my father left the table to phone home.

When he came back, we knew something was wrong. With my dad, you could usually tell when something was wrong, but you never knew exactly what. I thought maybe my brother and I were taking too long to eat. I mumbled to my brother to hurry up. My father stared out the window and told us both to hurry.

After we left the restaurant, we went back to our yellow raft, which was pulled onto the rocks under a bridge. My father had us sit there and he knelt in front of us. The river was dark brown, turning darker where it flowed beneath the bridge’s shadow. It was cool there. The sun was bright and the bushes and trees were green on either side of us. A car or truck would rumble overhead and the bridge would shake a little. My brother began to mound up dirt between his legs.

My father looked down for a long time, then looked up at us and said, “Boys, the dog got hit by a car. He’s dead.”

I don’t remember what I did right away, but after a few moments, I got up and hugged my dad, sobbing.

It’s hard for me to think of this even now. I wish I could say that my father hugged me back and sobbed with me, but he didn’t. I began to feel foolish and childish and overwhelmed by my father’s discomfort. I felt alone and vulnerable.

I stepped back from my father with more pain than when I went to him. I wiped my eyes and held my breath, scrunching up my face to stop the crying.

I glanced at my brother. He was scared, unsure, searching our faces for a clue as to how to feel. He looked that way during the entire ride home. I stared out the window. My father stared at the road. No one spoke.

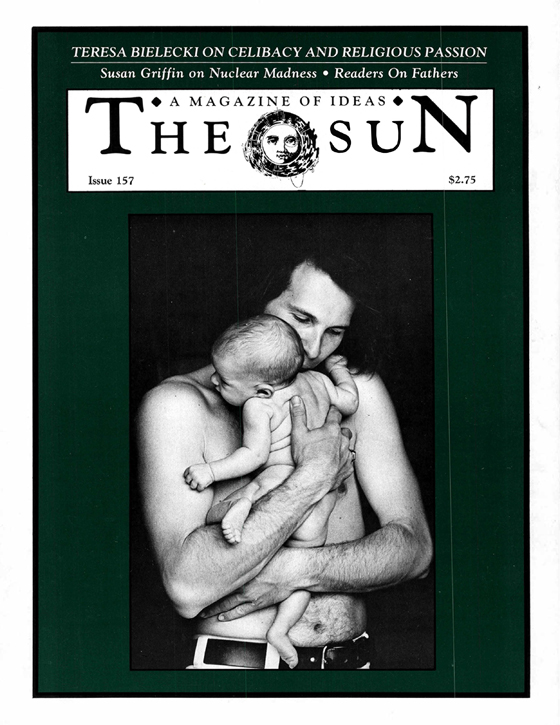

I’m thirty now. I have a seven-month-old daughter. Sometimes when she cries I leave her alone with a pacifier in her mouth, and I go stare out the kitchen window. Sometimes I hold her in my arms, and we stare at each other and cry.

Virgil Hall

Salem, Oregon

We had a rusty, old, heavy, green swing set. My days were spent on the wooden seat, whose slivers only I knew how to avoid. If I put my fingers in my mouth after holding the chains, they tasted bitter and it made me spit.

That swing was my best friend. When my parents would start to fight, I’d go to my swing. When all the other girls were at a slumber party, I would spend the evening on my swing and not even feel jealous. I would make a wind that would love up my face and hair. I was sure nothing could be as good as reaching my toes high and tilting my head back far enough to see the yard upside down. The rusty squeaking kept the rhythm as I made up song after song for myself. Our house was ruled by my father’s heavy hand; the swing was my safety zone.

When I turned eleven, my father decided that I was too old to swing and that I needed to make some friends. I got home from school one day just as my father was directing a truck out of our driveway. My swing set was on it, resting on a pile of scrap metal.

Within months I did have some friends and was smoking dope daily. My rusty green drug was gone.

Debra Rae Sikora

River Falls, Wisconsin

We pull out of the harbor, past the gray, piled rocks of the breakwater where pelicans sit. Small swells form, and break against the hull with a wet, slapping sound, and the rich stink of the sea is overlaid now with diesel exhaust and the mustiness of old burlap sacks. Arms crossed on my life jacket, I sit on the kill box and try to quiet my stomach.

Some miles out we slow down, and Dad lowers the lines into the water. Sticking out from the boat, the high, canted poles make us look like an insect floating on its back. We take our positions, one to a side, watching for the slight tug on the line. We wait. My neck gets stiff and my eyes dry out from staring. No salmon, just jellyfish. Dad cusses as he baits the hooks again.

Off to starboard, I see a crowd of gulls working the water. We head that way. Dad sees — or maybe feels — the strike on the line when it comes. “It’s a big one,” he shouts when the fish first breaks the water. His excitement is as taut and focused as the line.

I’m not sure what to do until he tells me to get the net. Hurrying to the stern with it, I stumble on the deck and have a sudden vision of myself overboard, thrashing and sinking. Intent on his catch, Dad doesn’t see my misstep, only the net in my hand. He lands the fish on the deck, a big salmon with plenty of fight left. I look down and away as he kills it in one blow with a baseball bat.

And there it is — death, the great, dark secret of life. A creature once streaming with vitality and purpose is caught and plundered by another’s need for food — the skin flayed, the guts opened to the light, the flesh eaten.

My father’s knowledge is potent and dangerous; so is his skill. He hunts what I consume. Now some of that power rests in me, if I can embrace both my animal self, struggling like the fish to survive, and my primal hunger for food and ritual, exulting with my father the hunter.

The queasiness that has been growing in me becomes urgent. Adrift in a small, pitching boat, rocked by an enormous ocean with its trillions of lives, each life fed by a million deaths, I want the certainty of land.

“Can we go home now?” I ask. Father and daughter, we turn and head for shore.

Shannon Nottestad

Half Moon Bay, California

I saw him cry once: the night my mother died, in a car he was driving. He sobbed in the kitchen. I was twelve. I hugged him, but he sent me away. He didn’t touch me again for months, and then he beat me because I didn’t eat my hot dogs and beans.

He sits behind me in the van — I’m driving him these days — and, his wheelchair fastened in place, he looks out the front window over my shoulder at where we are going.

I know when he will speak, and I know when he is worried about the road or the way I am driving. He is sometimes lost in a tightening spiral of apprehension, as he watches the road come to meet him in a world where the reins have passed to others. At those times I speak of nothings to distract him.

Yesterday, as we neared the nursing home, having taken the last bump in a very bumpy road, I heard him say quietly to himself, “I don’t know how much more of this I can take.” He was glad to be going to his nap. To me, his comment was a reminder of the preciousness of our time together. Even as I mourn the loss of our vitality, of so much of the persona I used to know, I celebrate the loss of that part of me that didn’t see his beauty and couldn’t understand his wounds, because they mirrored mine. I see now that they were his gift to me.

Sally Lonegren

Greensboro, Vermont

My father is a distant, unemotional, impersonal man. My only warm memories of him are from my early childhood, when he would sit me on his lap to read the Sunday comics. He would read them all, skipping only “Apartment 3-G” and “Mary Worth” but never “Mark Trail” or “Steve Canyon.” I also remember his patting my tummy after breakfast and proclaiming that I was full. These are the only physical contacts that come to mind, other than frequent punishments, such as spankings and having my face held down in a sink full of water.

I saw him kiss my mother three times in twelve years. I was three years old the first time. I asked Mom to kiss him so I could watch. Already I was aware that something was different at my house. Anger and violence prevailed over love.

I saw him cry once: the night my mother died, in a car he was driving. He sobbed in the kitchen. I was twelve. I hugged him, but he sent me away. He didn’t touch me again for months, and then he beat me because I didn’t eat my hot dogs and beans.

Sometimes I think I’ve spent my whole life striving for approval from him. When I was sixteen, he said those coveted words, “I’m proud of you.” I had eaten a piece of chicken in a restaurant with a knife and fork. When I graduated from college magna cum laude, he said, “I never thought you’d do it.”

When I was pregnant, he would tell people, “I thought I taught all my kids better than to have children.” He was only half-kidding. Now that I have a child, I am a little more acceptable to him as a person — but not much. Recently, he sent me an article on discipline.

In light of all this pain, I find it almost incredible that I can have a healthy, joyful relationship with a man. My mate is a wonderful father, physically affectionate and emotionally involved, loving and open. I watch myself carefully for signs of my father’s parenting style, but I never worry about my husband. For him, “father” is an active verb. I’m glad I was able to choose a man who welcomes and cherishes physical contact, whose parental pride has very little to do with polite dining. With this man’s help, I have found pockets of forgiveness for my own father. Because in his distant and unemotional way, he was doing the best he could — loving his family the only way he knew how, learning his lessons and helping us learn ours.

J.D. Kain

Vita Point, Virginia

To earn my allowance, I had to shine my father’s shoes every Sunday night. In my parents’ bedroom, in the middle cupboard, was a wooden shoeshine kit. It had a lid with a triangular piece of wood on top, on which you could place your foot while you buffed your shoe. From the assortment of Kiwi waxes inside the box, I pulled out the black and polished my father’s oxfords, whether they needed it or not.

At first I was timid. Why did this man who hardly knew me want me to shine his shoes? Eventually, my hands became so familiar with the shoes that I could wax and buff without looking. I would put my foot in each shoe as I buffed it, propped on the lid. In the closet mirror, I saw the huge shoe with my tiny foot inside, my small hands flying over the sleek leather with the combed-cotton swab. The wax became warm and pliable, its musky odor filling the whole room.

I began to linger over this last step. I liked the way my foot felt inside there, nearly swallowed by the crevices formed by my father’s hard-working toes. He wore those black oxfords every day, until the crevices became so big he had to buy a new pair.

I’d ask myself why his shoes had to be so shiny. If I did a crummy job, would he stay home from work for once and just be with us? But I always did a good job, and dingy shoes would not have been enough to keep my father away from his office, from his beloved job.

Atticus Finch, a father I read and dreamed about, would rush home from work and hold his daughter on his lap before she went to bed. Atticus once told her that you could never really know a man until you got into his shoes and walked around in them.

Gail Russell

Louisville, Kentucky

I forgive you. I forgive you for falling off a pedestal you never asked to be put on in the first place.

Dear Daddy,

Last year I went to a psychic who told me he saw someone around me whose face and head was shielded by a hood. I thought it might be you, since you shot yourself in the head. It made me feel good to think you might be hanging around.

A psychologist says we must integrate our fathers. This means that the daughter must separate her idealized view of her father from the reality, and see him as a flawed human being. Only then can she absorb his good qualities into her own psyche. My problem with you has been just the opposite. I saw you, near the end, only as a flawed human being. I realize now that I’ve never forgiven you for falling off your pedestal.

You and mama died within one year of each other when I was in my early twenties. Mama went first, at forty-two, from a heart attack. I went to the mental hospital to break the news to you. You’d been there quite a while, diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenic. When I told you, you didn’t seem very surprised. All you said was, “Well, they finally got her, didn’t they?” I still can’t get that picture of you out of my mind — you were just sitting there, staring at nothing, your fingers yellowed with nicotine from all the Pall Malls you smoked.

When I was little, you were big and strong. We were friends, wrestling buddies. Once, I was playing under the sprinkler, and you had just gotten home from work. You were so handsome in your business suit. I stepped on a piece of glass and cut my foot pretty badly. You scooped me up in your arms — you didn’t even care if I got blood on your suit — and carried me in the house where you ran water over my foot to stop the bleeding.

You started getting sick when I was in the third or fourth grade. I remember being very mad at you, hating you for being so weak. We were never buddies again. I could barely stand to be around you, and when I was, all I could do was talk back to you.

After I got married, our roles changed even more. I was the parent and you were the child — a very passive child who acquiesced to any decision I made about your treatment. You can imagine how surprised I was when I found out you had shot yourself in the head during a visit to Granny’s. I remember thinking that it was the first real decision you had made in years.

I found a letter the other day that you had written to your ex-employer about a month before you killed yourself. You wanted to make arrangements for me to get whatever little money you had coming, so I could take care of my little sister. I had seen the letter before without connecting its date with that of your death. I realized then that even though you couldn’t take care of yourself, you were still trying to take care of your children. I had always thought you weren’t even aware of us.

I’m writing now, Daddy, to tell you that I forgive you. I forgive you for falling off a pedestal you never asked to be put on in the first place. I forgive you for being flawed. And I know if it were possible to ask you to forgive me, you’d say there was nothing to forgive.

Patricia Bailey Marshall

Fredericksburg, Virginia

I remember him diddling me, fondling me, fucking me. He started abusing me sexually when I was an infant. My first clear memory is of him fondling me to orgasm. We were standing in a crowd of partially naked people in a large cavern. My mother and two men were in front of us, participating in a sexual satanic cult ritual. There were hundreds of people in orgiastic excitement, as if everyone were in heat.

My father was the local leader of the cult. By the time I was born, he and my mother were completely involved in it. I saw him cut people to pieces with his machete. I watched him meticulously peel the skin off people before he killed them. He taught me how to torture people to death. My father and my mother and all their friends — everyone I knew — were in the cult. They all abused me sexually.

What confused me is that my father was the only one in my childhood who showed me the slightest caring. I had to believe that he loved me. He gave me an occasional soft look, a look that I now know to be simple, raw neediness. Sometimes he displayed an openness that the others didn’t have. It was all I had ever been given, so I forgot the abuse and pretended that my father was safe.

In order to survive, I had to let go of the illusion that my father loved me. My sister and I used to talk about our memories. When she said to me, “I don’t want to lose the love of my father,” I sat back in my chair, knowing she was caught in the trap and that there was no way for me to help her. My sister still can’t let go of the insane dream that our father cared about us. In order to survive, I had to let go of her, too.

I used to see my mother as the villain. I made my father invisible so that I could preserve the illusion of his love for me. Now I see him clearly. I feel him beating me, his face set in rage and his eyes crazy-bright. I can feel the pain, now. I can cry, sob out loud. I never could then. If I cried, or made any slight whimper, it fired his rage. He hurt me in many ways, but something tells me that his worst abuse was to teach me never to make a sound.

Name Withheld

I can feel the pain, now. I can cry, sob out loud. I never could then. If I cried, or made any slight whimper, it fired his rage. He hurt me in many ways, but something tells me that his worst abuse was to teach me never to make a sound.

When I was four, my dad left my mom. I was in the hospital at the time, having the first of six surgeries for a hip dislocation.

My father had been working late, as he often did. When he got home, he threw his coat where mother was dozing, waiting for him, and said he was leaving her for another woman. That was that — no trying again, no fighting. Mother never asked for more than anyone wished to give.

She remembers lying on the bed and crying for weeks. I remember the nights she stayed up sewing sequins and ruffles on dance costumes and prom dresses.

I remember winter dawns, my nose against the window. Enchanted, I watched her shovel, wishing vaguely that I was strong enough, that we had another shovel, that I could even put on my boots alone. Then I could have run out into the drifts and helped.

I remember summers at camp — paid for by her typing work. Mountains, friendships, and vespers by campfire became the patchwork joys of my youth.

I remember the person who put me through college on a secretary’s salary, still paying off my operations.

Maybe that’s why, when sorting through Christmas cards last year, I had the odd feeling I’d opened someone else’s mail when I came to one signed, “Your Dad.”

Chalise Miner

Shawnee Mission, Kansas

He doesn’t acknowledge the strength and courage that it has taken to live his life. He accepts that life is hard, and he expects little from it. I respect him more than he could understand.

I’ve never met anyone like my father. For almost thirty years he has sketched portraits on the boardwalk in Atlantic City. He also paints and sculpts in a small room in a dilapidated apartment building. Though his work rivals anything in galleries, no one sees it but me, and those who visit my house, which is filled with his art. He is shy and soft-spoken, and the glitzy world of galleries and schmoozing with collectors is totally alien to him. He paints and sculpts because he has to.

In this culture, fathers are supposed to make money, buy cars, and be caretakers; my father writes poems and walks to the boardwalk in a blizzard at night to feed an abandoned cat. His silver hair is long. I’ve never heard him speak ill of anyone.

The child of a sailor and a seventeen-year-old dance-hall girl who died when he was two, my father was raised to believe that his grandparents were his parents. When he was fifteen, they both died. Going through their papers, he learned that his parents were in fact his grandparents, and that his dead sister was his mother. Now completely alone, he lied about his age and joined the army. He grew up there, as an infantryman in World War II.

To be different in a culture that rewards conformity exacts a price, and he has paid it. As his daughter, so have I. He doesn’t acknowledge the strength and courage that it has taken to live his life. He accepts that life is hard, and he expects little from it. I respect him more than he could understand. He is the best person I know.

Deborah Wiley

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

When I was a child, he knew the world. He removed his hat at the right moment in church — I followed with my bonnet — and remembered when to sit, stand, kneel. He mowed grass so that the clippings fell in neat, straight rows. He knew the name of each tree we passed on Sunday afternoon walks. He caught crawfish and boiled them until they were tender, never rubbery. He silenced the clanks and clinks of any car. He rode me on his crossed leg, higher and higher until my horse was Pegasus, flying to the ceiling.

I nearly broke his heart when I was four. He talked of it for years. A nurse was wheeling me to surgery — only a tonsillectomy, nothing serious. But I screamed like I was being tortured.

“Just let me get my daddy. I’ll be right back. I just want my daddy.”

“If only I could have grabbed you back, I would’ve,” he told me years later.

Now, my mother asks him, “How many children do we have?” An easy test, you would think.

“Two?” he asks hopefully.

“More than that,” she says.

“Twelve?” he guesses.

“Oh, not that many,” she says tenderly. “Seven. Don’t you remember seven?”

“Seven,” he says. “Of course, seven.”

I leave the room when she asks him to name us. It would break my heart to find my name missing from his list.

“If only I could grab you back,” I whisper.

Jacqueline M. Guidry

Kansas City, Missouri

So many different men exist inside my father. Some of them — the husband, the son, the father to my brother and sister, the alcoholic — I know through observation. A few others I’ve merely heard stories about — like the soldier who courted my mother or the interrogator in Vietnam. The only ones I know well are those that have been a father to me.

The one I loved the very best was the man who was my father when I was nine. I call him my fourth-grade father. It was a golden year that fell right after his first trip to Vietnam and a year before his second. That was the year he helped me learn to ride a bicycle, and then got me a beautiful turquoise Schwinn for Christmas. He took me to my new school to meet my teachers with me. The class had already begun writing in cursive and multiplying four-digit numbers. I was behind, so my father sat with me night after night, overseeing my homework. He never really helped me — he liked to push me to learn on my own — but he was there, that year, if I needed him.

That summer I had a minor operation requiring a stay in the hospital overnight. He took me there and brought me home. Later that summer, when he drove my grandparents back to New England, he took me — just me — with him. We stayed in Maine for a week that felt like three months. Every day my Dad and I went somewhere different — a carnival, an animal park, the historic village of York, the salt-water taffy store, the beach. We must have talked a lot during all those times, but I remember only the sensation of being alone with this incredible, attentive man.

In the fall, I joined the Girl Scouts. When our first cook-out was cancelled, I was very disappointed. My father packed up some food, and off we went, hiking through the thick autumn woods behind our house. He carried me across the deepest part of the creek on his shoulders. He showed me how to make a cooking pot by stringing a coffee can over the fire. When it was time to go home, he tried to teach me how to find my way by the sun.

When parents were asked to volunteer for Scout outings, my Dad was there. When I had to find twenty-five states whose names were of Indian origin, he stayed up with me, poring over the encyclopedias. He showed me how to fashion bowls out of clay. We were to dress in costume for our Indian show; my father made me an elaborately decorated Indian dress, using my mother’s sewing machine.

I wasn’t the only one who got this special attention from my father. On Easter, he got up early to hide our baskets in the house and eggs all over the back yard. At Christmas, he orchestrated the popcorn and cranberry stringing. On Sundays, he would cook brunch, inventing new dishes like “jelly omelets.” One rainy Saturday, he marshalled the family together to play games, magically pulling out a bag of toys and candy to use as prizes. On another Saturday, we were mysteriously whisked into the car, and we ended up at the circus. It seemed as if he were truly with us each moment, playing and giving, and loving the role of husband and father.

At the end of that gloriously happy year, this man left, and an entirely different one took his place. The new man was sent to language school in Washington, D.C., where he forgot that he even had a family, living instead the life of a carefree bachelor. I never saw my fourth-grade father again.

Memory is so selective. I remember that year in winter-crisp detail, while all the others are as faded as cotton sheets dried too often in the sun. Nearly every story I tell of my father comes from that year. Because of that year, I believe that I had a happy childhood. On the basis of that year, I forgive my father everything that’s happened since.

Since then, my dance with my father is always the same: I am an aching child, longing for his attention and love and approval. I want to be special. The year I was nine will always be my treasure because that was the year he was the father I’ve always wanted and needed him to be.

Kristy Taylor

Durham, North Carolina

My mother asks him, “How many children do we have?” An easy test, you would think. “Two?” he asks hopefully. “More than that,” she says. “Twelve?” he guesses. “Oh, not that many,” she says tenderly. “Seven. Don’t you remember seven?”

Baseball and opera were my father’s two passions while I was growing up. The droning sound of a baseball announcer’s voice always brings back memories of sweltering days long ago, when my dad sat in his DeSoto in front of our row house, listening to the ball game on the radio, shaking his head in disgust at how the Phillies were disgracing themselves again. (The reception must have been better outside, because I can’t recall his listening to the game in our house.) He was joined by all the other men in the neighborhood, who were also sitting in their cars, listening. No matter how badly the team played, my dad went back for more. He would take me to games at the stadium, patiently explaining things to me.

As a teenager, my dad had lifted weights in a gym above an old garage. He and his buddies, who were all Italian, would listen to opera records while they worked out, inhaling the fumes from the cars below. Sunday mornings in our house meant classical music and opera. My dad, who rarely showed any emotion, became visibly moved when he heard the opening strains of his favorite arias. He would wave his hands in time to the music, like an impassioned conductor, eyes closed, transported to another world.

Some of my father’s appreciation for baseball rubbed off on me. Not too long ago, I obtained two free tickets to a home game and excitedly invited my dad to be my guest. I could smell the popcorn and hot dogs already. On the appointed evening, we took our seats behind home plate. After a few innings, during which I kept sneaking glances at him, my dad abruptly said, “This game is boring. I don’t know what I ever saw in it. Let’s go.”

I scored better with opera. Once, when I was living 3,000 miles away from my father, a few bars of a poignant aria went through my mind. I was tormented by not being able to conjure up its name. It was almost midnight on the East Coast, but I took a chance and called my dad, humming the bars to see if he could remember the name. He hummed back and gave me my answer. Not too long after that, when I had moved back to Philadelphia, I asked my dad to join me for an afternoon of “Tosca.” I can still recall seeing that wonderful look on his face again — he was all choked up, wiping tears from his face.

Even now, it’s hard to say how much of my love for opera is for the medium itself, and how much is my way of getting closer to my dad.

Donna Greenberg Root

Huntington Valley, Pennsylvania

When two FBI agents came looking for me at my parents’ home, my father, who disagreed with my views on the war, called me and said, “Two of your punk friends were here today. I asked them if they were in the FBI to get out of the army and then I kicked their asses out.”

My father was a volcano filled with terrible rage. The slightest provocation made him so violent that I was sure my life hung in the balance.

If I spilled a glass of milk, chairs overturned instantly, dishes broke, a lamp crashed to the floor. His belt was whisked through his pant loops and became a weapon of incredible pain in his powerful arms. I remember being a little girl, trembling, whimpering, begging him not to beat me in the few seconds before he began. Sometimes, I would later discover that I had wet my pants while he beat me. He would knock me into walls, kick me, and throw objects at me — his face a red fireball, his veins distended down his neck and arms. It seemed that only exhaustion made him stop. The beating went on interminably, my mother pleading with him all the while to stop.

Alone in my room, I would sob in my pillow to muffle the sounds, lest they provoke him further. The real pain was not from the welts or the bruises all over my body, but from the fear that he had wanted to kill me and that I had narrowly missed death. I even felt grateful to him for letting me live.

Money was also a serious problem. My father would occasionally gamble his entire paycheck at all-night poker games. During every bitter Pennsylvania winter of my childhood, we were without fuel for days, sometimes weeks. Other times, our utilities were turned off. Sometimes we sold furniture to buy food. Everything I wore was donated.

I struggled to overcome my fears not only of my life and my father, but also of the world. Constantly I imagined catastrophes everywhere: trains would run over me, cars would crash, wild animals would escape from their cages and eat me. I would be murdered in my bed. Many nights, I would sit at the top of the stairs, too frightened to sleep, yet terrified to cry out for help from parents who would not come. I despaired of ever being safe. My mother was too depressed and too sick to do anything to protect me. Even today I often feel certain no one cares. Almost daily, I confront irrational fears.

During the fourteen years I lived with my father, I avoided him in every way I could, every minute of every day. Still, when his rage erupted, I became the target. His nickname for me was Spook because when he came close to me I flinched involuntarily like a skittish colt. In his warmer moments, he would want me to sit on his lap. But there were obvious sexual overtones, and I was too frightened to comply. This infuriated him and in seconds his “warmth” turned to rage. I remember the terrible dilemma of not wanting to placate him and being terrified of the consequences if I didn’t.

Even as a third-grader I knew at some level that my father’s fury was a horrible crime. But I was afraid of what could happen to me if I told the wrong person and my father found out. I planned to escape, but there was nowhere to run. No one could make life safe for me — a feeling I still struggle with today.

Once, in the middle of a snowstorm, our school bus broke down, and my teacher took me home to spend the night with her. She was so kind and took such wonderful care of me, making me grilled cheese sandwiches and hot chocolate, and tucking me into a high, quilt-covered antique bed. I struggled with the idea of telling her my story, but I was stopped by the humiliation of it. I was ashamed to tell this lovely lady, who thought so highly of me, my awful secret.

I survived by entering a convent school at the age of fourteen. I was able to stay there until my parents divorced.

I have spent years in therapy and self-study in order to feel safe. I continue to heal each day. It is still a nightmare for me to hear children crying, or to see them punched and beaten at stores and in parking lots.

Name Withheld

He walked briskly through the front door into the living room, removing a white handkerchief from his shorts pocket. His white, V-neck T-shirt was soaked with sweat. He took off his glasses, wiped his forehead and eyes, looked at me, and said, “If a centipede a pint and a millipede a quart, how much can a precipice?” His shoulders heaved with mirth, and he laughed, as if that were the first time he’d heard it himself. I stared down into the book I was reading, smiled, and shook my head.

I relied on my father for advice when I stumbled into puberty. “If there’s anything you want to know, son, just ask me,” he said as he left the room. He taught me how to work. “You’re not good, son, but you are slow.” He knew how to get his children to settle down for the night when they were a bit rambunctious. “You kids get to sleep up there, or I’ll come rock you to sleep with real rocks!”

When two FBI agents came looking for me at my parents’ home, my father, who disagreed with my views on the war, called me and said, “Two of your punk friends were here today. I asked them if they were in the FBI to get out of the army and then I kicked their asses out.”

He had a thousand jokes and I heard them a thousand times each. What he taught me about golf, I could have learned on my own in the first half-hour (“Damn trees! That ball must be part woodpecker!”). He never agreed with my politics. But he was always there for me, a loving and good man with an odd sense of humor. I always had a place to stay, and he always talked to me. His best advice didn’t come from what he said, but from the way he lived and treated people. His love and example were gifts to me, and these memories carry me through good times and sour.

Craig Convissor

Howard City, Michigan

Everyone tells me, “Sparrow, you’d be a great father.” (Because I love jokes like: “Why is the turtle green?” “Because he isn’t ripe.”)

All my life, it seems, I wanted to be like my mother — strong, brave, loving, and, above all, practical. Reality was reality. There was no sense arguing with it, or trying to change it to suit my whims and ideals.

But Daddy and I are more alike than I would ever have wanted to admit while I was growing up. There were things my father could neither understand nor accept. The difference between what was and what should be caused him pain. That pain showed in his eyes, along with a little boy’s sense of joy and wonder.

Daddy was not like the fathers of my friends. He spent hours upon hours, day after day, in the woods. He hated it when the party was over. I often saw my father cry. He could play and joke like any ten-year-old. He was not practical, although life and circumstances often forced him to be. He did not want to accept things as they were. He did not understand the part of humans that placed more value on money than on nature. I remember hearing him exclaim many times, “The almighty dollar! That’s all they care about! What about the woods? What about the deer? They are pushing them back, pushing them back. Taking over their territory. Where are they supposed to go?” To him, it was no coincidence that “devil” and “developers” began with the same three letters.

Often, his passion embarrassed me. When I was in high school, we fought. He’d rant and rave over the fact that my boyfriend had the longest hair in the school (this was in 1969), that we were hippies. I’d tell him, “Oh, Daddy, you know you were the world’s original hippie, only you won’t admit it.” But my friends — even my boyfriend — all loved my father. He was fun and knew how to be with kids. When they would come pick me up to go out, it would be hard to tear them away from Daddy. They admired him for what he knew about the woods, and they loved listening to his stories.

I often felt that Daddy didn’t love me enough. He had a hard time expressing his love to people. This hurt. Yet, I have the same problem — it’s something I work on. Now that I’m older, I can forgive the pain my father has caused me. When I look into Daddy’s eyes, I see myself. We are alike. We are both idealists. We fight unrelentingly what we are told is reality. We share the same pain.

He calls occasionally because, he says, “You understand.” The other night he called because a developer just won his case against the town to put in a golf course, a hotel, and 130 condos near Echo Lake, the woods he loved, the woods where he took me as a child to teach me the most important things — animal signs, the names of trees and plants, what the deer and the bears fed on. In these woods lived a friend of his — Hunky Dick — in a tiny log cabin next to a brook. He pumped water by hand, had an old Victrola, and liked his home brew. I loved being there. Hunky Dick is dead now. The cabin collapsed long ago. Soon, even the trees will be gone. “The almighty dollar” won again.

“It hurts,” Daddy was saying on the phone. “It really hurts.” “I know,” I replied. There were tears in my eyes and I could hear them in Daddy’s voice. I, too, feel the pain of losing these woods.

I recently wrote a book about economics and the Earth. I dedicated it to my father — “To Daddy, who understands.” It was the best gift I could think of. I now see my father’s strength. It takes incredible bravery to feel our pain, every day, and not let it harden or destroy us. I am proud to say, “I am just like my father.”

Susan Meeker-Lowry

Montpelier, Vermont

When I looked at the topic for this month I thought it said, “Feathers.” “Here is something I know about,” I mused. Then I realized it was “Fathers,” and my heart fell.

Fathers? I only have one father, I thought — with the picture before me of The Man I Cannot Call Jack.

My father once explained to me The Principle of Regression, which accounts for why he’s 6 foot 3 and I was then about 5 foot 4 (though now, I just learned, I’m a quarter-inch shorter than T.S. Eliot). Also I should be less smart than he is, according to this theory.

When I studied at the Har Zion Yeshiva in Jerusalem, I learned that the orthodox have a grand version of The Principle of Regression — that each generation is inferior to the last, going back to the Fathers: Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. That’s why Jesus doesn’t impress them. “All the rabbis could walk on water back then,” they told me more than once.

Violet and I are talking about making me a father — and her a mother. Everyone tells me, “Sparrow, you’d be a great father.” (Because I love jokes like: “Why is the turtle green?” “Because he isn’t ripe.”)

Sparrow

The East Village

My father transformed a murky, wet bowl of mud and stumps into Pogo Pond. I was three, and the bulldozers were big. They were also yellow like my hair and the ever-brilliant sun which seemed to drench the pit with a warmth and protection that only my father could have called forth. I covered my ears and watched for hours, for days, and ran along the slippery banks with Willie. The hole became my playground. Willie barked at the Caterpillar and the frogs, and I laughed out loud.

My father also worked in a business suit and a hat, and was gone a lot. I learned to help with the paperwork when he came home, so that we could be together. He taught me to row, fish, tie knots, and capture frogs, and to name the trees and lilies and birds at Pogo Pond. I played outside in my skivvies as he painted the house in his. With my mom’s help, I tried to write him letters and poetry when he was away.

My father and I cried with the same tears one Easter morning when he told me that my mother was in heaven. I was ten and he was alone with me and Willie and Pogo Pond.

He built a new house, and I watched again as he hammered and moved dirt and planted trees, giving me strength. This house faced Pogo Pond from a slightly different angle. The sun was as luminous as ever. My blond hair was longer, and Dad helped me curl it. I cried because it needed to be curled, and he cried because his fingers were big and clumsy with the rollers. Later he bought me tampons and figured out ways to explain such things. He wrote me a letter every single day that I was away at boarding school, and I think it was in 1969 that I started sending him Mother’s Day cards. He understood.

He is sixty-four now. We recently made a trip to Pogo Pond together. He flew several hours to get there, and I drove from the opposite direction. The sun was brilliant. The water and the lilies seemed drenched with yesterdays. In its stillness, I heard the bulldozer groaning, Willie barking, and the frogs plopping. Tears spilled down our cheeks.

Jacqueline Germain

Middletown, Connecticut

If I wasn’t ready on time, my father would leave. He’d tap his foot and jingle his keys as if moments were spilling marbles. I had to walk fast to keep up with him.

Though I was always behind, I liked knowing he was somewhere ahead of me, pointing the way.

When my father was stabbed with a heart attack, I hunched in the intensive care waiting room, turning the pages of Southern Living. Beside me, a tattooed man cracked his knuckles, watched wrestling on the dim television, and thumbed through the Gideon Bible. My mother sat in the corner, wrapping blue yarn around her hands and pinching chocolate-covered cherries. When the nurses announced visiting hours, we crowded into the restroom and smeared on pink lipstick.

My father lay captive of thunderous machines and sinuous needles. An oxygen mask shielded his gray face. My mother motioned me out of the room when I cried. She was worried my father might notice.

For days, I sat in the waiting room, bones melting from boredom. I reread five-year-old Reader’s Digests and ate my mother’s pinched chocolates. I learned the names of the cookie lady’s grandchildren and the receptionist’s boyfriends.

I waited because it was too scary to be ahead of my father, to walk on ground he hadn’t yet seen.

When my father recovered, we went for a walk. We shuffled, shading our eyes from the stern sun. He moved like an old man. I had to slow down to keep up with him.

Deborah Shouse

Leawood, Kansas

I kissed my mother. I ran to kiss my father. He stepped back from me and said, “Boys don’t kiss boys.”

I was almost five. We were in the basement. I kissed my mother. I ran to kiss my father. He stepped back from me and said, “Boys don’t kiss boys.”

A thousand thoughts went through my mind, including, “But you’re not a boy. You’re a man.” But I didn’t say anything. I had trouble breathing, just for a minute. I tried not to show it. He didn’t do anything. My back was to my mother. She didn’t do anything either.

In a minute, I was all right. I knew a new rule. I knew my father was more different from my mother than I had realized.

Jon Remmerde

Bend, Oregon

My father was a preacher. In preparation for speaking, he would clear his throat in a peculiar way. He did this so that his words in praise of God’s Kingdom would have clear sailing.

Later, I discovered that it was also nervousness that caused him to do this. During baseball season, when I came to the plate, I would hear this distinctive sound from the stands. He wasn’t about to speak; he was just nervous — for me.

I can recall specific stressful incidents when I knew by this sound that my dad was there: the time I was standing at the free-throw line, only a few seconds left on the clock, one point behind; the time I was being wheeled into the operating room to have my appendix out; the time my eldest son was badly hurt in a childhood accident. Through closed doors, over the roar of the crowd, in the most unlikely and unusual circumstances, I could hear my dad clear his throat.

He died nine years ago. I don’t think of him as much now as I used to. But during moments of trial, I still find myself listening for my dad. What I miss most about him is that peculiar “ahummmm.” Even now, imagining this sound, I feel a calm descend on me.

John Babbs

Boulder, Colorado

When I was a boy, my father was always right. When I became a man, he was always wrong. Now that I’m a father, he is who he is.

Paul Moore

Berkeley, California

My father is preaching a sermon. Not in a church, from a pew, but in his bedroom, from his bed, in the dark. A crack of moonlight catches at his spectacles, and they glint at me, the only congregant here tonight — perched on the edge of his bed, ready to flee.

This sermon deals with my “wayward friends.” My father spits out the word, “Homosexuals.” He wants no homosexuals in his house. People will talk. This is a favorite phrase of his. People will talk. The neighbors will see, hear, talk, tell. I am irresponsible, immature, foolish — like my mother.

My mother, in her bed, silent until now, stirs in her sleep and turns over, making her foolish presence known. I edge toward the door.

“I have to go now,” I say.

My father sighs heavily. “She’ll never change.” He prods my mother awake. “Annie! What’s going to happen to her?”

Name Withheld

I recently read a story about a girl who worked in a nursing home and her friendship with an elderly male patient. The man was so kind and understanding that the girl came to love him. She was having disagreements with her own father at the time, and she wished he could be more like the kindly invalid.

The patient had adult children living nearby. The girl was indignant that they never visited him. Then the girl learned that her favorite patient had treated his children cruelly when they were young.

I remember a nicer story about a father, by a French writer. A young couple decided to postpone their wedding until they could save some money. The boy stayed in the village to farm, and the girl went to the city to work as a domestic. The girl became pregnant by another man and returned to her village in disgrace.

Hurt and angry, the young man repudiated her. But the local priest called him in for a talk. He told the boy that it was his duty to marry the girl and give her child a name. The priest urged the boy to be kind to the girl and her baby.

The boy married the girl and learned to love her son. The couple never had children of their own.

Twenty years later, his wife dead, the husband was a helpless cripple. All he had was his devoted son to take care of him and earn their living.

I cry every time I read that story. It’s about the way things should be but almost never are.

Mary Umberson

Paris, Texas

My arm went through his so that the insides of our elbows touched, and we talked of life and death and God. He spoke to me as an equal.

“Rise and shine. It’s time to leave!” Excited, he scooped me up in his arms and carried me through the darkness to my bed in the back seat of the car; over his shoulder I could see the first light of dawn. He thought every vacation had to begin by catching the 7 a.m. ferry across the Mississippi River at Helena. We always grumbled until the moment we drove over the top of the levee and saw the ferry.

We sat at the kitchen table, making up Droodles for each other to guess. “This one is Mrs. Norris,” he said. I turned it all around and peered at it from every direction, but it didn’t make any sense to me. Mother wandered through and glanced down at it. “Hal!” She grabbed it and walked out, as they both laughed. I drew it again later and showed it to my friends, but we never could figure it out.

I was playing on the old typewriter in the back room of his office. It was cool back there, but I felt comfortable and welcomed by the rows of heavy law books in their glass cases. “Sal! Could you take these papers over to the courthouse for me?” My favorite errand! I found the right place with no trouble — and a sense of pride. As I turned to leave, the lady with glasses behind the high counter spoke. “You’re your daddy’s girl, aren’t you?” They all laughed. I was too old to be talked to that way, but I was glad they knew.

“And I promise to wear no man’s collar.” It seemed like an odd thing to say in a speech to other fifth graders when I was running for class secretary, but most of the speeches he wrote for me were a little over my head. He had the most fun with the essay I had to write about chewing gum. I couldn’t use it, of course. Mother said my teacher probably wouldn’t appreciate the part about how Adam and Eve used gum to stick their fig leaves on.

Christmas Eve was always one of my favorite days of the year; it was the day just the two of us would make our important deliveries. First we would pick up cakes from the lady who lived beside the armory. Then we would ride all over to deliver them. The old man out in the country had real stuffed animal heads on his wall, and each year he would give me a silver dollar. The best stop was Mrs. Man Fong’s grocery store. She would give me a cart with two big brown paper bags and tell me to fill them with anything I wanted. Later, she would add boxes of tea, fortune cookies, and embroidered silk slippers. Daddy and I would ride proudly home, bearing gifts for everyone.

My ballpoint pen slipped smoothly over his soft skin. He was lying on his side in the big bed, with only his pajama bottoms on. This time his back was a busy train yard filled with all kinds of trains. I was drawing slowly, and he was trying to guess what it was. His guesses were all wrong, and I laughed at his silliness. I decided to make his two little moles into faces of people. “Please don’t wash it off yet,” I begged. He smiled and agreed. The next night he unbuttoned his shirt and pulled up his T-shirt in the back for me to see. My drawing had gone to court with him; it had sat with him in his office as he listened to stories of land sales and divorces. And it was still there.

He was sitting on the couch out on the side porch when he took my hand and pulled me toward him. He wanted to know what was wrong. I began to cry as I told him that all morning Griffin and I had had to do whatever Jessie said because she was descended from Jesse James. “Well, that’s nothing,” he said. “You’re descended from Billy the Kid, and he killed more people than Jesse James ever did.” What a relief! It was ten years before my surprised mother told me I certainly was not descended from Billy the Kid, and where did I ever get an idea like that?

We all knew there was a mouse somewhere in the house, and one day soon a trap would be set for it. But tonight was my night to try to see it. He sat me in the chair by the telephone, then put the food out like a dotted line leading from underneath the icebox to the middle of the floor. He solemnly told me not to make a sound or move a muscle; then he went out, closing the door behind him. After what seemed like hours I caught a glimpse of the whiskers moving just at the edge of the icebox. And as I held my breath, the little black eyes appeared, followed by the tiny ears, furry gray body, and long tail. He inched his way across the floor, pausing to look for danger before every bite, until he was only two feet away from me in my chair. Finally he stopped to wash himself before he scampered away under the icebox again. Minutes later I ran to tell everybody, but I still felt as if I ought to tiptoe.

The empty bottles filled the tool room. They were stuffed into paper sacks and stuck behind old cans of paint. Sometimes, I would go look at them, and wonder what they meant. One morning I saw him walking out of the tool room. “Don’t tell your mother,” he said. Tell her what?

I hated to go downtown barefooted. I worried about the spit on the sidewalks, and the brick streets hurt my feet. When I complained about the bumpiness, he just laughed and said that someday I would appreciate those streets.

I felt big and important as we walked into the courtroom hand in hand. He had his robe on. “I have to sit up here alone, but I made a place for you at the table with the lawyers,” he said as he led me over. They were men I knew, but the table was big and long, and I felt a bit foolish and insignificant. I wondered if the spectators thought I shouldn’t be there. I listened intently as people talked to Daddy and explained their problems. I watched his face as he looked kindly at them and listened. The last case was coming up, and at a signal from Daddy one of the lawyers took me out of the room to wait in an office downstairs. We passed some older boys with duck tails and torn shirts; they needed a shave. I sat alone and waited for him, humiliated about being taken from the room. He saw my accusing look. “I’m sorry,” he said. “I thought there would be some language you didn’t need to hear.” It didn’t help much; after all, I was ten years old.

He was leaning against the mantelpiece reading the note in his hand. He couldn’t speak. I had never seen him like that, so I sat down and waited. After he had left the room, I asked Mother what was going on, and she told me that Uncle Robert had committed suicide, and Daddy was the one who had found him.

Gray hairs bothered him, he said; it was bad enough being bald. So we had this deal: he gave me a penny for every gray hair I could cut out with the fingernail scissors. He would sit on the edge of the bed, and I would stand behind him, handing him the gray hairs so we could count them together later. Once, the scissors slipped out of my hand, and I froze when I saw that one of the tiny blades had sunk into his leg. I looked at his face, but he seemed perfectly calm. He just pulled it out and let me put some iodine on it.

We had already come in from school and were sitting around the living room when he came walking in the front door, ready for dinner. Mother went up to him and put her arms around his neck. As he kissed her, he put his arms tight around her waist, and when she picked up her feet he swung her around. I felt as if I should look away, but I didn’t.

I tapped softly on the closed door. Was he ready yet? My friends were huddled behind me, and we were trying hard not to giggle too much. “Come in,” he said, his voice mysterious and dramatic. We slipped in and closed the door, squinting to find the bed in the dark room. We snuggled in around him, and the story began. Tonight Blood, Guts, and Chitlins began their escapades by riding balloons up the hill to our house so they could sprinkle pepper in our noses and make us wake up sneezing. Those elves were always getting into trouble! Sewerpipe, the tag-along, was in this story, and I was glad; it always made me feel better to know there were others who liked to tag along behind the big kids. The story was over too soon, and a slap on our fannies sent us running for the door. It never did any good to beg for another story; they came only one at a time.

We sat on the top step and watched the sky darken as lights came on around the neighborhood. After a hot day, the tile felt nice and cool on my legs, but I welcomed the warmth of his body close to mine. My arm went through his so that the insides of our elbows touched, and we talked of life and death and God. He spoke to me as an equal.

We were walking up the steps to the front porch, coming in for dinner. My hand reached for his, and he shook it off. “I don’t need any help,” he said. I hadn’t known how weak he felt. “I’m sorry,” he said, with a look I didn’t really understand. I couldn’t bear to look at his face, so I looked at our hands.

Their bedroom door was closed again, and I could hear the voices, angry and hurt. I felt such a need to know. I sat down softly beside the door and leaned against it with my ear touching the wood. “Trying to find out about your Christmas present, huh?” Kay said triumphantly. No. But I skipped away, grinning and embarrassed. She thought it was funny. Would she tell them about it?

He gave me fifty cents, exactly what I had asked for. It made me feel funny. Usually when I asked for fifty cents, he gave me a dollar. Later I agonized over it. If only I hadn’t been asking for something!

I had spent the night with a friend, and it seemed strange that they brought me back home so early the next morning. Aunt Mary Frances opened the door to let me in. Her health was poor, and she hadn’t left her own home in several years. She said Mother was in her room and wanted to talk with me. When I went in, she was sitting up in the big bed. “Your father got worse last night. He died.” I lay across the end of their bed and stared at the wall. She said I would feel better if I cried, but I couldn’t.

Sally M. Thomas

Charlotte, North Carolina