Tuesday, September 9

I aim to do two things. To tell a certain story, and to please myself. To lay down words, neat as the logs in a fireplace.

There is wind here, leaves just beginning to turn. Damp pine smelling. Indigo sky.

A man lives alone. How do you tell that? With bed, bath, morning. Cup of coffee ground by hand. Poached egg. Dry toast. A walk by the water.

I live alone. Other men might be lonely. But who can notice what might be absent when other things are present? Before his death my brother Jake said, “I want my life to be used up when I die. I want the tube to be squeezed flat and the brush all smashed down.” Said in the hospital bathroom, sitting on the side of the tub.

A dog lives in this house. He romps and bays and sometimes feeds on squirrels. Who can blame him for that fury, teeth sunk in? A man is no better for his actions. He may just know how to keep his hands clean. And the birds play tag from tree to tree. Knowing one’s teeth and the other’s gun. This is the life of the forest. I cannot change it.

There is a town fifteen miles from here. With a car and a big freezer, a man only has to see other people every three weeks — once a month when the garden is green. Neat rows planted with packets on sticks. A deer shot now and again.

Bud, my sister’s son, comes to see me sometimes. No one else. And if I get a letter once a season, from an old friend or an interloper, I can answer it six months later. A letter perhaps from a friend in Europe, who still sends paintings, pages from sketchbooks. That friend of youth, which seems like someone else’s childhood now.

Can you tell a man who lives this way that he is wrong? Can a life be wrong? Can it be wrong the way a word in a puzzle is wrong? (Right number of letters, but wrong.) Can the weather be wrong? Or a nose, tilted too much to the right, or too long?

I walk in the forest. I send the birds up. Or I crouch to watch a family of deer munch leaves and spring on. And even now that I cannot walk so well, this forest is home.

Friday, September 12

The morning is crucial. Will the ride from slumber to work be easy? Or will the mind stay weighted, held back in the timeless morass, eyelids swollen? If the mind is alert, the hands work. And then the rhythm of hands, mind, legs is one. The turning on wheel, the turning with hands. They sink and rise up. They push into the wetness, trying to turn that constant shifting and sliding into something solid and enduring. Beneath glaze, baked and frozen.

When the headaches first came, Bud said to see a doctor. “I haven’t seen a doctor in twenty-five years,” I answered. Then the trembling began. You realize too late that pride, or laziness of habit, has prevented another artist from excising that which grows silently, which blossoms in the darkness. A fungus or Indian pipe. In the place of total darkness, it sends out roots. Then, the leg goes. So Bud brings a cane. And my sister Grace, his mother, calls. And what she says is, “I know. Like Gramps.”

Monday, September 15

Death is easy. Work is hard. I stare at the rows. Pots, unglazed, unbaked, or done. When is something done? When it’s perfect in the mind? Or the moment you let go of it? I threw a pot for Death. It is long and greenish blue. It rises up like a tulip from a bulb. The neck is much too long, long from waiting. And the mouth is much too small. Either from hunger, or from not being able to get anything in or out.

Bud said, “Why don’t you draw?” He brought me a book with blank pages. One arm has started to go. It’s harder to work now. But I do not see with my eyes when I work. I see with my hands. So the book went unused. I saw Bud want to ask. It sat up on the mantle, until words started to happen.

Monday, September 29

Bud pushes me through the forest. The wheels of the chair bog down in mud. He kicks branches under them, and hauls me up. “Look,” I whisper. “A stork.” He follows my hand up. Together, through the trees, we watch it soar and disappear, headed toward the marsh. For a moment the senses are pulled out of the mind like twine from the center of a ball, two strands together, his and mine, twisted together. And perhaps this is enough. Not the making, making, making, but just watching, seeing, waiting.

Later, afternoon

Bunker trots through the door, tail waving, a blue jay in his mouth. He drops it on the floor beside my feet. Then he grabs it again, shakes it in the air, and hauls off with it. Later Bud sweeps the feathers off the floor, grabs a chair and bangs down beside me to rage about Al. His anger is brutal, raw. Was I like that? Did I rage against my own dad like that? Have I forgotten the intensity? Or did age wear me down like a pencil? When he heads back to his car, I am glad. I remember how Grace was when she married Al. How Mother was against it, but never said. How Grace wanted her to say no, waited for her to say no, until it was too late. And then Janie came, Al Jr., Frank, Sally, Bud.

Tuesday, October 7

If I balance on the edge of the bed I can slip on my pants and wiggle them up. A belt is not important. Yesterday Bud and Al came down. They ripped out the door frame and put a bar in so that the chair could fit into the bathroom. Then they built a ramp down the porch, and another one up the steps to the studio. I did not ask them to do that. They did not ask me.

Bud drove into town for food. Al sat with me on the porch, with the beer from his back seat. He talked about Grace and the kids. He did not ask about me. There are two kinds of people, I decided long ago. There are the people you see when everything is fine, who take off when things get rough. Most people are like that, most friends. Then there are the people you only see when the going gets rough. They’re there in a pinch. Most family and some friends are like that. Al is like that. Bud, I think, belongs to both groups. I don’t think I belong to either. Before they left, I asked them to help me take down the curtains in the bedroom. Now from my bed, the green-blue face of trees, the birds, fingers of sun, they cut into the eyes’ first opening. Sparkling. Muted. Veiled. But present. Changing from day to day, but present.

Wednesday, October 29

The legs are gone. They hang from the hips like the stuffed legs of a doll Grace loved, with a little porcelain, painted face, that Aunt Louise brought her from France. To the touch, they are the same, and to the eye only a little changed, a little thinner, veinier. But the mind has already left them, rejected them.

Bud helped me. Bud moved chairs, a desk, a table. I can go anywhere in the house now in my chair. My arms get stronger as my legs go, even the arm that fades. The stove is too high for me to look into pots. If I’m too tired to haul myself up, I work by feel and smell. I see through the old wooden spoons. Yesterday the sun was pounding through the glass, and I started turning in circles on the linoleum, around and around like Jake and I used to do in our room in the attic at Gramps’s, till we collapsed on the floor with the universe spinning around us. The oatmeal burned. I didn’t care. The phone was ringing. I didn’t answer it.

Friday, October 31

Markham came this morning, to pick up the pots for Christmas. I asked him to come here. On the phone he said, “Cal, in twenty years you’ve never asked me there.” He sounded hurt. I was surprised. I said, “I was never dying before.” I showed him the house, the studio. I showed him the pots I’ve made for myself. The ones he could sell. The ones for my family. I gave him one of my best — wide, flat, open. Like the mouth of a valley when you come upon it at the beginning of spring, soft green with white still whispering across it. Pretended I’d made it for him. He pushed me to the lake. We watched two cardinals flick from branch to branch, a male and a female. Red and russet among dark branches. Everything a hush when they were gone, as if they’d taken something with them that needed a moment to rise up from the dirt and the rocks again. As he got into his truck I called out, “Drive carefully.” Who said that, I asked, startled. Ashamed I might have said it because of the pots.

Night

I have an old pipe. It was my father’s, the only thing of his I have. Unless I count the nose (without the break I put in it), the cleft of chin, the thick black hair now just beginning to show gray. I light that old brown pipe with the black, chewed bit. I talk to him. “What do you think of your son?” I ask him. He says, “Work comes easy to some people. And living comes hard, I guess.” He is wearing his green and mustard plaid coat, the one Mother hated so. He looks about my age, a little younger. I tell him how I always thought smoke ought to come in different colors. I can see it drifting and circling to the ceiling, changing as it passes through the pool of lamp light. He does not laugh. He does not seem to think about it. I wheel myself into the living room and pull myself onto the couch. I want to feel the old sagging pillows again. Bunker whines and nuzzles up beside me. He buries his head in my lap. I remember how he came here, in a shoebox. Brown and tartly sweet-smelling. He licks my face. I scratch him just where he likes, where the neck bones go into the skull. Markham asked me about the doctors. He made me tell him. How the headaches began in July and the trembling in the leg started in August and how I went to the doctor in September. How I continued to work. But. . . .

Saturday, November 1

That old teapot never cracked. Even today when I hold it and pour, the thin arc pleases me. How long was it that I destroyed things, saying I wanted to be a potter, not make pots. Until I made this teapot.

Bud says to get an electric wheel. I say it’s too late to change now. I became a potter and now I am done.

Sunday, November 2

I remember going to church with Granny Ellis. I thought about it because it was very still this morning and I could hear the bells in Schuylerville.

Grace called. She wants me to take vitamins and do a cleansing fast she heard about on her favorite radio talk show. I laughed. I said I’d always wanted to die in my sleep or be hit by a car. But I’m beginning to like this slow shutting down. It’s like getting to see the movie of childhood in reverse, that most of us can’t remember.

Two deer came up to this house today. Stopped by the porch. Looked up at the window. Did they see me, old man in wheelchair, before they bounded off? Four hard points to touch the earth with. And me with my two wheels. Ears peaked to sounds I cannot sense. All points and solid lines — legs, ribs, neck, head. Leaping off through the blueberry bushes, dragging the wind along with them.

Friday, November 7

There are ways to see. I took Bud to the studio and I pointed. That pot is Aunt Doris, I say. Why is it Aunt Doris? Bud fumbled for words until I explained how a pot can be a portrait, or more like a story. Tall and thin like she is, with dark glaze, but brittle, long, narrow neck, unstable base. Made him try to guess the others. He found Grace and Al and cousin Wilber. Missed Janie and missed himself. Broad and thick, wide mouth, heavy, dark base.

Sunday, November 9

Mist rises over the lake. A single dead tree, twisted branches. Black against gray. No bird, no squirrel. Toe on worse foot no longer wiggles. I push myself out here, and bring this book with me.

Friday, November 14

Bud again. He takes everything down from the upper shelves in the kitchen, the bedroom. I told him what it was like to clear out the old place after Gramps died. Fifteen-year-old coupons in kitchen. Ration book from World War II in the desk. Old hutch in the dining room stuffed full of old brown paper bags, organized by size, with colored bags in a different section. A lifetime of old rubber bands and string. I tell Bud that I need to clean up before I go. He gets mad. He says he’s tired of helping me do cleanup. I know that what he means is he doesn’t want to think about my dying.

I’m sitting on the porch when Bud drives off. I wave. He waves. Bunker comes back. He must have heard the car. He barks and leaps up on my legs, clawing. He wants me to go racing down the road behind the car with him. I wave him off. I notice that where he scratched the left leg I hardly feel anything at all. He tears off, after the dust on the road.

Tuesday, November 18

Cold, and it’s funny how parts of me feel it and parts of me don’t. Last year when Grace talked me into finally putting in a furnace, I was angry. But without it, I couldn’t be here, couldn’t cut wood, haul, stoke. Do we know these things? Does some part of us know it? Did Charlie know the morning he drove to town but never came back? Did Dotty Lou know? Is that why she finally started talking to Grace again after all those years?

Thursday, November 20

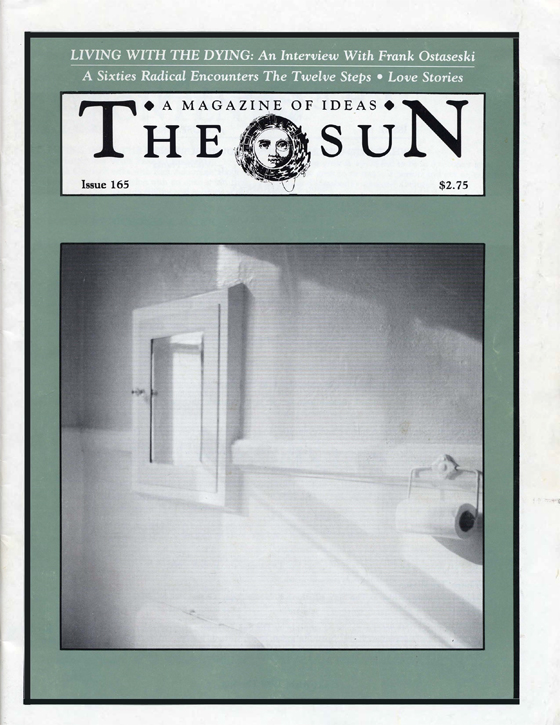

First frost. I took the mirror down from the bathroom door and propped it up against the wall, at an angle. Now, from the bed, I can look at the reflection of the sky, empty or clouded.

The other leg is going, the better arm is getting worse again. I didn’t feel anything in my right toes this morning when I pulled myself out of the tub. I was so angry I started smashing them up against the side of the toilet bowl, wanting to knock feeling back into them, but only bruising myself. Part of me is dying and part of me is finally ready to live. Markham calls and we talk for an hour. When did we ever do that in all these years?

Friday

Bud pushes me to the lake. If I could stand I could see it from the porch now, with all the leaves gone. Strange that I can’t. I just see sky. This must be the beginning. Bud says he decided to take a leave of absence from school to think things out. I know that Al wouldn’t care, but I can’t believe that Grace let him. Then I realize what he’s up to. We’re watching two ducks on the water and he’s talking about not knowing what he wants to do, could I show him about pottery. I say I have to think about it.

Sunday

I ask him to take me to the bathroom. It’s a test, for both of us. He gives me a funny look that says you were fine all weekend. I say, “If you help me now when I don’t need it, it will be easier to ask when I do and feel too proud.” I can still grab on to the bar he and Al put in, but for how long? He says nothing. Afterward he reminds me that he’s been an orderly every summer at Springfield Hospital since he was sixteen. I don’t say anything. I don’t say it’s only been two years. Grace calls. She says, “I want you to know this wasn’t my idea, Cal. It was his.”

Thursday

He sits by the window and plays his guitar. He plays it softly, but I don’t want him to play it at all. Bunker is sitting at his feet. A fire is burning. The snow is falling. I stare out the window. I see shapes and feel things in my hands I cannot make. I watch his fingers on the strings. One arm is almost all gone now. In order to move it I have to pick it up like a doll and deposit it where I want it, on lap, on arm of chair, on table. In his face I see myself as I was, I see my dad, I see Gramps. Brooding, turned inward and brooding.

Grace and Sally come, with pots of food and packages. Sally carries four months of her first baby. She laughs and oozes contentment. They say they came to see how the boys were doing, see that they didn’t starve themselves. I want to say something about what difference does it make whether it’s fast or slow, but I don’t.

We sit and eat pea soup like Mother used to make and honey bread that Sally baked. For the first time, Grace asks me why I left. And why I came back. I tell her I wanted to see the world. Then I saw it and that was enough. Bud says someday he’s going to take off and never come back. Tibet. Bali. Africa.

December

Some nights I can’t sleep. Other times I sleep all night and all day. Everything is jumbled. Time and past time. People long dead show up. Charlie, Gramps, the baby Ella Ruth had who died before being named. Bud comes and goes. Sometimes I ignore him, pretend to be asleep. He’s like a ghost too. Only Bunker is real. Leaping up on the bed, draping himself over my legs and not even wondering why I stopped kicking him off.

Christmas

Grace and Al and all the kids. Kids and kids’ kids. Bunker, not used to company, leaping and barking and grabbing food out of people’s hands. I give the last pots away. I told Grace I would only let them come if they didn’t bring me anything. They do anyway. Books and music, a tape recorder, a new quilt. The snow has painted crescents on the windowpanes. The house glows bright from sun reflected. Bud pulls all the curtains back. The tree shines with all the old balls and clay animals I made for it. Everyone is laughing and talking. Babies seem to be crawling everywhere, on the floor and up the walls and on the ceiling. These and the ones we were when we were babies. All flapping around my chair, in the center of the room, that Sally decorated with pine branches while I took my bath.

I read the words back. Bud plays one of his tapes. Bunker snores by the fire. Everyone has been gone for two days, but I still hear the talking and the noise everywhere. It bounces off the walls. It bursts out of a pillow when I lean back into it.

The sky is orange. The wind howls. Even the good arm is going. Bud’s hands feel like my hands now. He reads me the news from the paper.

Light everywhere. Sky indigo pot upside down. Bunker barks at back door. Light barks into twilight. Fades. In the dream everyone is there.