My abortion was the first real thing that had ever happened to me. This was the mid-seventies in New York City. Despite my nice, upper-middle-class, unbroken home, I was a thoroughly decadent young girl. At my birthday party that year everyone yelled, “Sweet sixteen and never been fucked by a dog.” I laughed because I really had done everything else: I had been to bars, clubs, and even a few orgies; I had done various drugs, slept with assorted boys and girls. But I had never given myself to anyone or anything with a whole heart.

I knew the symptoms right away: sickness at the smell of cooking meat; lassitude; a faint rising sensation in my lower belly. I was so sure that when my first test came back negative, I returned for another. It was the same gynecologist who had delivered me. Through a mask of disapproval and anger, he said we would schedule the operation for the following month.

“Why do we have to wait?” I asked him.

“If it’s not big enough, there’s a chance we might not get all of it,” he said, looking away.

I went into his bathroom and threw up among the urine samples.

I didn’t want the doctor to perform the abortion. He had been so cold and mean at my examination. I hated the idea of facing him from the stirrups as I went under general anesthesia. But my mother trusted him, and she was the one footing the bill.

She never asked me how I felt about the abortion, or why I was sleeping with people I didn’t love; she just said once, curiously, “Do you enjoy having sex at your age? Do you have orgasms?”

“Yes,” I lied. If she had them, I would, too.

My father, as usual, made more of an effort but missed the boat anyway. One night he came in with a present for me: a fake-denim blank book with a little pocket attached to its cover. It was hideously uncool. Then he hesitantly told me he had thought it over and decided that abortion was really no different than birth control.

“Thanks,” I said, turning away from him, tears in my eyes.

I completely disagreed. All the comfort in the world couldn’t make me pretend that abortion was simple prevention. It was something big, dark, and painful.

“Think of it as ringworm,” said a friend who lived in one of the nicest buildings on West End Avenue and had lost her virginity at twelve. “It’s just a parasite.”

Ringworm could never become a child; the blob of cells inside me would, if given a chance, squirm into the world, to mewl and cry, to climb trees — one day, perhaps, to write poetry. I could feel the life rising in my sixteen-year-old belly and it was not ringworm. It was unthinkable for me to bear a child but I wasn’t going to lie to myself either.

Walking up West End away from my friend’s house in the bright sun of a late summer afternoon, I was so sad. Surrounded by helping hands, I knew I was alone. It was the strongest, truest feeling I had ever had.

Name Withheld

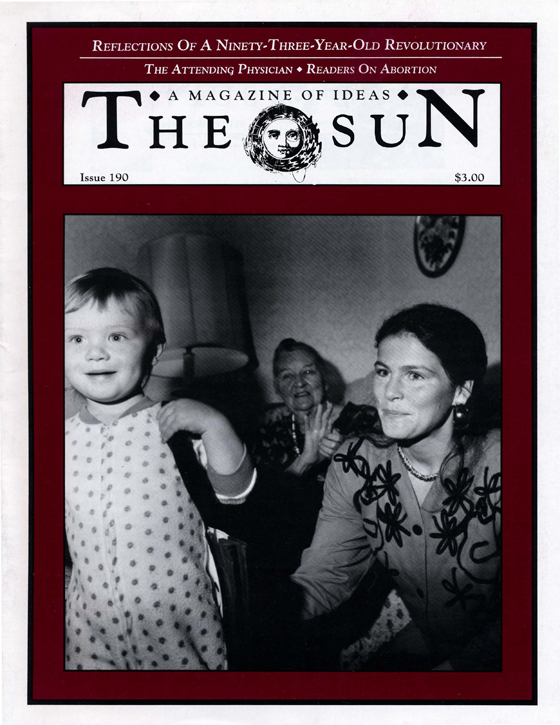

When I walked in the bathroom nearly three years ago and saw that the tip of the test stick had turned a bright blue, it was a devastating shock. I was an unmarried young woman, but I knew immediately abortion was not an option for me. Only now can I say with complete clarity why. As I carried my daughter Madeline for nine months she was no less unique, full of life, demanding, or beautiful — and certainly no less human — than she is as she stands before me today. If you respect all human beings equally, I see no choice.

Mary Barnas

Portville, New York

In 1970 we moved from Los Angeles to Philadelphia. Since I had been raised by the proverbial love child, the move to the puritanical East Coast was quite a shock.

I met Aaron. He was radical, idealistic, cute, and sixteen. When I told him I was pregnant, his age and vulnerability became quite clear. Abortion had only recently been legalized in New York. I remember feeling lucky to live so close. Keeping the baby was discussed, but we were realistic about the situation.

Getting a legal abortion in the seventies was harder than getting an illegal one. After the doctor verified the pregnancy with applications and paperwork three inches thick, we had to go to a rabbi to discuss our problem. Because I was Catholic, I also spent several days in counseling, repenting for my sins.

Carrying two hundred dollars, we finally boarded a train for New York. Another passenger had a transistor radio. I kept hearing the chorus of this one song: “Where are you going, my blue-eyed son, where are you going, my darling young one?” I started bawling, which was kind of stupid, as neither one of us had blue eyes. We arrived at Grand Central Station and took a cab to a renovated office building. Inside we found a small, clean waiting room filled with red-eyed teenagers and pale, shaky parents. I talked with fourteen-year-old Shelly from Georgia and twelve-year-old Vicki from Illinois. During the operation itself, I stared at a field of daisies tacked to the ceiling, while the doctors and nurses talked amongst themselves. They didn’t say anything to me. I sensed their disapproval. The procedure lasted only ten minutes, but I knew the memory was forever. Afterward, I devoured a whole can of peanuts and three Cokes. Aaron, who wanted to make the best of a sad situation, decided we should go to Coney Island and ride the roller coaster. After I threw up all over the people in front of me, we headed back home to Philadelphia.

Two days later, we had a big fight. I was irrational, throwing plates, screaming, crying. I didn’t know that I was having the baby blues. I was still a baby myself. That was the end of Aaron and me.

To this day I don’t eat peanuts. I don’t drink Coke. I can’t stomach roller coasters and I still cry when I hear that song, “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.”

Theresa

Port Orchard, Washington

My sister’s abortion made a pro-life crusader out of her. She was fifteen. The father was a boy who happened to be black, or a thirty-five-year-old truck driver who was married. My mother wasn’t about to find out which. We drove the forty miles to the public clinic. We said almost nothing. I could have stayed in the waiting room with the tearful women and sullen young men, but I escaped outside. I killed a good half-hour peering in the windows of the pharmacy next door, reading boxes and labels. Another hour went into exploring the neighborhood. I can recall each shoot of dandelion breaking the sidewalk, but I still have no real idea what she went through, frightened, draped, clobbered by drugs.

Name Withheld

“Promise me that if you ever get pregnant and don’t want or can’t keep the baby for whatever reason, you’ll consider letting me and Jim adopt it.”

I promised to consider it. She was my college English teacher, nine years older than I. She and her husband couldn’t have children and they sort of “adopted” me the summer I was twenty.

Later, at the age of twenty-six, I found myself pregnant. I was leaving for graduate school and the last thing I needed was a baby. I thought about her request and then put it aside, believing that I would not be able to give up a child I had borne. I had an abortion. It was the first of three.

Now I am forty-four, married with two half-grown children by my first husband, and two almost-grown stepsons.

She is starting a new career as a recently ordained minister in a small, poor church. Her two adopted children are grown and on their own.

Today is her fifty-third birthday and I call halfway across the country to wish that it be a happy one. I can hear Jim in the background. She laughs and says, “He’s guessed that you are calling to tell us that you are pregnant and going to let us adopt the baby.”

I feel my heart drop. “No,” I say. “You know, I’ve had three abortions.” A confession. A completion.

“No, I didn’t know. I mourn them.” She says this sadly and without judgment.

I sit quietly and allow myself to feel her loss and somehow, again, my own.

“So do I,” I am finally able to whisper.

Donna Nassar

Glen Ellen, California

My friends dropped me off at midnight outside a deserted park in New Jersey. They were told to wait for me at a diner down the hill. I was to wait for a black, unmarked car to transport me, and others, to an unknown destination. It was 1965. I was young and scared. Having a child I could not support was even scarier. I was returned to my friends at eight the next morning. They had waited all night, without knowing what was happening.

Back in my apartment in New York City, it was immediately apparent something was wrong. A frantic cab ride took me to my doctor’s office. An ambulance rushed me to the hospital. Several transfusions replaced the blood I’d lost.

Three months later I was diagnosed with a bad case of hepatitis. I was in the hospital for thirty days, on bedrest at home for three months, and unable to work for an entire year. When my recuperation was complete, and the last blood test was taken, the doctor revealed I almost died several times.

I am thankful abortion is now legal. My life was changed forever on that day in 1965.

Caryl Ehrlich

New York, New York

I had the dream in one version or another during the three years I worked in the clinic and for some years thereafter. Sometimes, the baby would lose itself in the darkness of the womb, slipping off into a far corner as one dilator after another pressed through the cervix. Sometimes, it would be caught before it disappeared, flying swiftly up the cannula, a clear hollow plastic wand attached by a hose to the suction machine. Sometimes, I would see it briefly, the tissue clinging to the mesh bag, before it disappeared into the container the doctor sent to the lab.

It was called “the procedure” by everyone at the clinic. The intention was to protect the woman having the abortion, to soften its impact on her life. For there was always an impact, even under the clearest and most freely chosen circumstances.

There were other fragments of the dream: the sound of breath held high in the chest against the pain (which we were careful to term “discomfort”); the smell of blood and of fear — a hot, close smell; the feel of a woman’s hand in mine squeezing tight. Sometimes the ring I wore cut into my finger.

In one dream I was using an adding machine to calculate how many abortions I had helped women through. There were four a day, sometimes five, sixteen to twenty a week, perhaps eighty a month. The tape was curling in heaps around me like so much cut hair. Once, years later, I dreamed I was back at my job only to find I had forgotten how to do it — I put the pads on backward, got the birth-control information wrong, lost critical lab work, and slipped up by calling the procedure an abortion and the fetus a baby.

Kathleen M. Kelley

Williamsburg, Massachusetts

I was raped. I never called the police and certainly never told my family. In the sixties, the way to get an abortion was through the underground. I went to San Francisco for arrangements and then had to get to Mexico.

It was a border town, hot, dusty, and strewn with corrugated shanties and cardboard lean-to’s. The people’s poverty pushed against me harder than the heat. I shaved myself the night before the abortion, as I’d been told. I watched the curly black clumps fall, swirl in the water, and disappear down the drain. The next morning I found a deserted phone booth on the outskirts of town. I had to use a code name. It was like an espionage film, except it was real, more real than most of my life had been to that point. It was a hurried exchange. A stranger’s voice tight with caution told me to be in front of a designated department store. There would be three other women and we were to come without companions. A taxi would pull up. There would be three possible greetings: one signaled it’s “on”; another, it’s “off”; anything else meant the driver was an undercover agent so get the hell away.

That evening, the taxi was late. When it finally pulled up, the “on” code was used, so we got in. We rode for almost an hour in circles through back streets, making sure we weren’t being followed, making sure we inside were lost. We finally stopped in a narrow dirt alley. We went in a back door and were met by a woman who spoke only Spanish. She indicated that the doctor would come in a few hours and left, locking the door behind her. We waited: an overweight wealthy girl, prim and petulant; a sickly youngster, tense and gray; a wiry woman from Berkeley; and myself.

When the doctor came in, he put tubes into us and directed us to narrow cots in a small, windowless room. We waited as knots of contraction began. It was hot and the blood was thick about us. The frail one was crying, then moaning. We tried to calm her, to give her comfort, to silence her calls, but we couldn’t move because of the tubes in our birth canals. Suddenly there was a violent pounding on the back door. It was a group of drunk men. They yelled threats and obscenities. They knew who we were, what we were doing here.

The doctor returned at four a.m. to anesthetize us, then scrape the uterus. I remember him telling me to breathe deep, telling me to count slowly to ten. I never reached four.

By six a.m. we were wandering the streets, dazed and weak, thick wads of cloth rolled in our pants to catch the blood. Before we left, the doctor had pulled me aside: he told me if we hemorrhaged or developed a fever to get help immediately. He gave me some little white pills for the pain. He seemed a good and kind man.

A.L.A.

Santa Clara, California

I was breaking up with my first lover. As we argued over whether breaking up was wise, we made love. It was four days before my period was due, so I didn’t bother to use the diaphragm. My period didn’t come.

This was 1963, and abortions wouldn’t be legal for ten years. Luckily there was an underground network of doctors who would help students out. My boyfriend and I borrowed a friend’s beat-up car and drove five hundred miles to Baltimore.

A taxi dropped me off in a ghetto of boarded-up brownstones. I wore a pink cotton dress I’d sewed myself, short, with puffed sleeves. The doctor was Chicano, the nurse black. As she held my hand, the nurse asked, “Is this your first time?” The gas didn’t help. I could feel the pincers deep inside me. A poem kept going through my head, the line “ran the wound too deeply, to the quick of me” repeated over and over. When the operation ended, the doctor, soft-spoken, even tender, carried me to a couch in a darkened room filled with books and gave me a pill to ease the cramping. He didn’t even look in the envelope to count the $250.

Driving me back to the hotel where my white-faced lover waited, the doctor told me, “Now, no intercourse for ten days.” I kissed his cheek, my savior. I was free.

K.S.T.

Tallahassee, Florida

For three days Jim didn’t even call me to learn the results of the pregnancy test. Later he told me he had hoped it would just go away. When he did call, he told me he couldn’t live with himself if he didn’t stand by me. He agreed to pay for the abortion and any counseling I needed. Gratefully I accepted the offer.

I had told myself that I would never have an abortion. My cherished brother was born because of a last-minute decision not to have an abortion. Now I didn’t even think. I just knew I had no desire to have this baby.

I saw a therapist recommended by my friend Rachel. Dora suggested that I consider the baby my teacher. I didn’t know what he was teaching me but I named “him” Guru, or Baby Roo for short. I began to allow myself to know him, just a few cells I imagined curled up, all tiny and tender inside me, innocent and sleeping. I began to allow myself to love him. I acknowledged the protective feelings I had for him. I was swollen, but amazed. My body could do this. The rest of me would not.

The day came. The waiting room looked like the lobby of a good hotel. Lots of women, some girls. I waited with Rachel and Jim. Then I was given a paper gown and slippers and shown to a changing booth. Fifteen of us, each in a paper gown, waited on benches in a small room with no carpet. When our eyes met we smiled, but mostly we looked down. It was cold in that room. Cold, cold hands. Cold feet.

In the examining room, a tall, good-looking nurse had me situate my feet in stirrups. She placed a speculum in my vagina. Cold. I asked her if she’d ever had an abortion. She looked at my face for the first time, paused a moment, and said, “Yes.” My name was called again. The nurse put her arm around me and helped me off the table.

In my paper gown and shoes, I walked to an operating room. I lay on the paper-covered steel table (so cold, a steel table). Another set of stirrups, another speculum. Another nurse sat at my head and held my hand. The doctor walked quickly into the room. He didn’t meet my eyes, but he did say hello. He disappeared behind the tent of my raised knees.

I felt a pinch. I felt a cramp, then nothing. Baby Roo had been sucked away. The doctor disappeared. The nurse helped me off the table and led me to a room with a narrow cot. She put thick sanitary pads between my legs and told me not to move. I lay down and waited.

When the shock began to clear, I got up. The nurse helped me find my clothes. I walked out into the waiting room to find that Jim and Rachel weren’t there. I was too early. They’d gone to breakfast. I sat and watched the women and girls waiting. Jim and Rachel came back and hugged me. We walked into the bright sunlight.

Jim took me home and I went to bed. I had never felt such an emptiness. After hours of tears, I slept in Jim’s arms.

The next day I wanted to go out. Jim needed to buy something so we went to a mall. I saw couples with babies and children. I felt a longing to be that ordinary.

Jim and I have been married six years. I feel very ordinary and very blessed. We have never had the desire to have a child. But I am deeply grateful for the baby we had.

Gretchen Newmark

Portland, Oregon

I have a friend who almost bled to death from a legal abortion. I have four friends who experienced extreme trauma and grief years after their abortions. Two of them, while still pro-choice, feel they weren’t properly counseled beforehand; they weren’t given enough information to make an informed decision.

I have many friends of color who sincerely believe abortion is being forced on the black community as a way to control their population, as a form of genocide. As one woman said to me, “We don’t need fewer babies, we need more chances to produce another Martin Luther King, Jr.”

I have a friend who grew up dirt poor, picking cotton, eating beans every day. His mother gave birth to thirteen children and raised them herself. Today, that woman would have been counseled after her third, fourth, or fifth child to abort the rest.

Yet, all thirteen kids in that family earned master’s degrees or better. Is there anyone who would argue that our society in general, and black society in particular, would be better off with fewer educated, accomplished black men and women?

But these are things we, on the Left, aren’t supposed to talk about.

Certainly, given the nature of this society, it’s difficult to argue that abortion isn’t a necessary option. But the truth is, the Left doesn’t want a debate on abortion any more than the Right does. Both sides want blind support for their positions. Such closed-mindedness prevents us from discovering how we might create a society where abortion, while still legal, won’t often be necessary.

It’s often suggested that a child will hinder a woman’s “career.” This assumes a person’s job is more important than the people in one’s life — a conservative, patriarchal notion. To say that a career woman, or a poor woman for that matter, should have an abortion so as not to lower her “quality of life” is to reduce her life to a mere cost-benefit equation. This is the logic of capitalism. In accepting it, we embrace a repressive economic system, and make no effort to change it.

I’m not saying abortion should be illegal. I’m saying that we need to work toward creating a society where abortion will be unnecessary — a society of fairness and inclusion, where children and mothers are valued as much as VCRs, or a title before one’s name.

There is no way to know what a child will become. A compassionate society would recognize this, and welcome pregnant women with celebration and joy and hope — and do everything it could to insure that each child born, each woman who gives birth, is afforded the same opportunities as everyone else.

Name Withheld

In November of 1979, when my husband went on a trip with a friend for several weeks, a man broke into our apartment. Years earlier, when our daughter Sara was just a baby, there had been a prowler when I was alone with her. That time I had awakened and frightened him away with a rage that disguised my fear. This time was different. I didn’t hear. I woke to searing pain and vituperative threats.

When the man left, I began a ritual of bathing that I repeated for years. Then I took Sara and went to stay at a friend’s house. As the days passed, I told myself that John would say what I needed to hear and I would be clean and safe again.

John returned and I told him. I immediately regretted my words. The look on his face was one of utter revulsion. He asked why I let it happen when I had stopped a prowler before. When I tried to explain the fear, there was only an uncomprehending stare.

I had thought there could be nothing worse than the assault, but telling John was far worse. A few weeks later, I realized I was pregnant. John assumed that I would terminate the pregnancy.

While sitting in a doctor’s waiting room, I realized that abortion was not the solution. For me, it would only continue the assault. Again I would be robbed of dominion over myself. The assault and the accompanying abortion would have the same source — the hatred that spewed obscenities and threatened butchery. I would be again smothered by the darkness. This potential child was not the pain and fear of the conception, nor the person who had hurt and terrified me, nor even myself. This was a separate person. If I could love this child — with the same adoring tenderness that I had for Sara — I would cheat this thing that tried to drag me into darkness.

Throughout the pregnancy I talked to the child, just as I had with Sara. But I felt nothing. There were nightmares. My nausea had more than a physical cause. John left for weeks at a time, several times. During the other pregnancy he had gone out in the middle of the night to find a deli that had kosher dills and vanilla ice cream. During this pregnancy I didn’t know where he was in the middle of the night. I did not understand why he did not leave completely. We had never been legally married, but had lived together for a decade. There was nothing to keep him from leaving, except for the promises we had made.

When the baby was born I was relieved that it was a girl — one less link. I wanted this child to feel that she was rare and precious. I thought of how close Sara and I were. I wanted this child to have the sense of connection between mother and daughter. Still, I felt nothing.

Then John began to have violent headaches, blackouts, abrupt changes in mood. We learned that he had inoperable brain tumors. The next few months seemed ringed by death. I continually reminded myself that love sometimes has very little to do with feelings, that feelings are a generous bonus. Love is often concerned with such things as bathing away feces, seeing repeated nights with only a few hours of broken sleep, blinking away tears caused by an aching back.

John passed into a coma and died without any sign that he despised me any less. His face carried the same revulsion as when I first told him. Amy was almost a year old, and still I felt nothing for her.

At Christmas I took the girls to midnight Mass. A woman read from Isaiah about how a people who had lived in darkness had seen a great light. As she read, we passed the light of candles until the church was ablaze with light. Standing in that growing pool of light, I looked at Amy and was overtaken by joy. Love had come in like a flood.

If the intensity of that moment had been fleeting or never repeated, it still would have been enough to sustain me. It has not been fleeting. Instead I have been awed by the depth of my love for her. Love is not something we can define or hold with words. It is something with the power to define us.

I look at both of my daughters and try to see if I feel differently about them, if I feel more mother to one than the other. I can discern no difference. I look at them and only know that I love them.

Amanda K.

Springfield, Oregon

In 1969, before abortions were legal, high-school girls in the white suburbs of Chicago relied on a word-of-mouth network that stretched thirty miles into the black ghettos. That’s how I ended up, on a gray November day, in the basement of an inconspicuous brick bungalow in a South Side neighborhood as bleak as the bare, cold sidewalks.

The abortionist met me and my three friends at the door, sat us down in his living room, served us screwdrivers made with vodka and Tang, and disappeared downstairs. I wondered whether it was wise to drink alcohol, but figured it must have been all right or he wouldn’t have offered it. What else could I think? I had already decided to trust him — a man I’d never met — with my body.

The house looked so normal. There were built-in bookshelves in the living room, a china cupboard in the dining room, a kitchen down the hall. It was easy to imagine a Christmas tree in the corner and smiling relatives gathered around the dining table.

The door to the basement opened. He came up wearing a white lab coat with dried blood down the front. He stood in front of me, waiting. I handed him the wad of money, knowing it wasn’t enough. This was the moment I’d feared most. He silently counted it twice. It took a long time because there were mostly ones, fives, tens, and a few twenties. Four-hundred and eighty dollars. It was supposed to be five hundred dollars. Please God, I thought, don’t let him say he won’t do it. The four of us blurted supplications, cataloging the allowances we’d saved, the stereo we’d sold, the friends and strangers we’d begged money from in the halls at school, the sixteenth-birthday savings bond we had cashed. I vowed over and over to send the twenty dollars just as soon as I could, all the while thinking: you bastard, I’ll say anything to get your operation. That twenty will be my revenge for you standing there in that bloody coat.

He must have known he’d never see it, but probably figured that four hundred and eighty dollars was good enough. We went to the basement and he sat me on a narrow table in a closet. He asked if I was allergic to anything. Then he gave me three shots. Two of them were something called Midnight Sleep. They hit as I walked back across the basement to wait in a big, vinyl easy chair for my turn. My legs buckled. By the time my friends had settled me into the chair, I was incapable of moving or even speaking. All I could do was gaze up at the stained ceiling tiles.

I have no memory of moving back to the operating closet. During the procedure I opened my eyes. I saw him huddled by my feet. My friend Nancy sat to one side, holding my hand, stroking my forehead, and whispering that it would soon be over. Later she told me she’d been there the whole time and she’d thrown up once.

I called him again a month later, as he had suggested. He asked whether I’d had any bleeding, any pain. The answer was no. He didn’t mention the twenty dollars.

Linda Gibson

Tampa, Florida