When I was ten, I said a crematorium was an ice-cream parlor for dead people. Even as my father laughed, I knew that fire ravaged the body, that it shattered the hair first and then peeled the clothes away. But the invention felt good on my tongue. All through school I couldn’t stop; hallways throbbed with my voice, my deceit filling the air with static and wonder: “The Spanish teacher wants to sleep with me,” I told friends between the thin gray lockers; and, to a bejowled principal: “Thomas Edison almost married my great-grandmother.” My English teacher encouraged me to write it all down; my English teacher with a vein of numbers tattooed on her forearm. “We told stories to stay alive,” she said. “To us, the Nazis weren’t even humans.” On the last day of school, our bus stopped at a railroad crossing. My eyes followed the boxcars as they lazed by. I could picture the countless hands sticking through the slats, rain skidding across their fingers, their open palms stunned by the cool spring air.

Independent, Reader-Supported Publishing

Poetry

Telling Stories

Free Trial Issue

Are you ready for a closer look at The Sun?

Request a free trial, and we’ll mail you a print copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access — including 50 years of archives. Request A Free Issue

Request a free trial, and we’ll mail you a print copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access — including 50 years of archives. Request A Free Issue

Also In This Issue

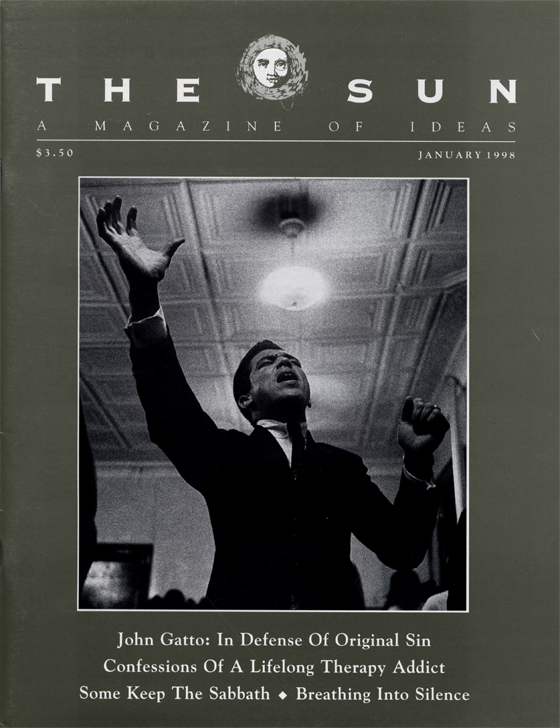

January 1998

close