I am sitting with my parents in a restaurant only a few miles from where I grew up. Our dinner conversation meanders like some venerable stream through well-worn and familiar channels. My mother does most of the talking. She talks about Ethel Nussbaum, who has breast cancer, and Doris Steinmetze’s son, who is now an ophthalmologist but is considering going into hair transplantation because the money is better, and the cruise she and my father took last summer to Norway, and how nice the retirement home is that they are planning to move into someday — but not yet, she says for what must be the hundredth time; we’re not ready yet. My father jokes that they are doing their damnedest to spend my inheritance, and I say something jokingly in return, only my father is nearly deaf now, so I have to repeat myself, and the second time it comes out a little too loud, with none of the humor that I originally intended.

These days, when my parents and I get together, it’s usually in a restaurant like this one. The food is mostly indifferent, or occasionally good, but I don’t really pay much attention. My mother eats quickly, just as she always has, making rapid little birdlike stabs with her fork. Sometimes, when talking and eating, she gets mixed up and forgets to close her mouth, and I catch glimpses of her half-chewed food. By contrast, my father is always very careful to keep his mouth closed while chewing. This forces him to breathe through his nose, so that I can often hear him inhaling and exhaling as he eats. When I was younger, especially in my teenage years, my parents’ unusual eating styles were a source of irritation and embarrassment for me, but neither of them ever appears to be bothered by the other in the least.

It’s been a long time since my mother actually cooked a meal for me. The truth of the matter is, she is not a very good cook. She probably inherited her meager culinary talents from my grandmother, who used to boil her chicken without mercy until the skin of the poor bird, in some ghastly final surrender, turned a puckery white, like the ends of your fingers after you’ve been too long in a bath. I think cooking offends my mother’s sense of order. Cupboards must be opened, neatly stacked plates disturbed, troubling gaps created in otherwise perfect rows of sparkling drinking glasses. When I was growing up, my mother was a dynamo in the kitchen, madly careering from refrigerator to stove top to table top; flinging open cabinet doors and slamming them shut again with the sound of rifle shots; juggling plates, glasses, and silverware with one hand while tossing salad with the other. And all this concentrated effort, all this blinding speed, with but one aim in mind: to get it over with so she could get the mess cleaned up.

At the restaurant, my father asks me how my night-school class is going. He asks me this every time we get together. It’s part of our ritual, a little dance that we do, the father-and-son two-step. As always, I tell him that night school is going well, and, as always, he asks me if I’m getting college credit. We’re gliding gracefully about the restaurant now. Well, I say, I could get credit, I suppose, but what would be the point? I’ve already got a degree. I just enjoy taking classes. (You’re dancing divinely tonight, Dad.) Yes, my father says, but as long as you’re paying the money you might as well get credit for it. (You’re not doing too badly yourself, Son.)

When the waiter arrives, my father orders the veal; my mother, the swordfish. As usual on these occasions, I’m feeling slightly nauseated. The very last thing I want to do is eat, so I order the chicken, the most innocuous-looking food on the menu. But it’s not that easy: Will that be string beans or squash with your chicken tonight, sir? Baked potato or rice? Thousand Island or bleu cheese? Yes, sir. Excellent, sir. Very good choice, sir. The waiter is unctuous and needlessly formal, clearly passive-aggressive. My parents, of course, miss this entirely. They think he’s wonderful, calling him by his first name every chance they get. In another minute or two, they’ll be asking him to sit down with us. I, on the other hand, would like to smack him in the nose.

Was there ever a time when I was comfortable with my parents? I try hard to think what it was like when I was a young boy, but the few memories I have are often murky and slightly out of focus, as if seen underwater. And my early recollections don’t seem to add up to much, often more annoying than useful. For example: once, when I was five or six, I somehow wandered into my parents’ bedroom and found my mother lying half naked in my father’s arms. Although I would have it otherwise, the image of my mother’s ass spilling out from the bedsheets remains firmly fixed in my memory. Unbidden and for no discernible reason, it can float lazily into view at any time, apropos of absolutely nothing, like a big white balloon.

And then there’s the time that my mother bought me a pair of long underwear for a family ski trip. I was maybe eight. She told me to go upstairs and try them on. They were tight, I remember, but I got them on OK and went back downstairs to show her. My father was there, too. He looked at me with a queer sort of smile on his face and told me that my penis was showing. Alan, he said, your penis is showing. Just like that. Five simple words, out of all the millions I must have heard spoken around that time, and those are the ones I remember. What chord was struck that long-ago day, what inner bell so solidly rung that nearly half a century later it continues to chime? Without meaning to, I glance down to make sure my zipper is closed.

My mother, who has a little piece of fish lodged at the corner of her mouth, is telling me about her friend Rita Cohen’s son, who has just expanded his dental practice. She asks if I remember him, knowing full well that I do. (My mother and I also have a dance, but it’s more complicated than the one I do with my father, more dangerous. A tango, perhaps.) Peter Cohen and I were best friends in sixth and seventh grade, and I’m glad he’s doing well, although I don’t tell my mother this. He and I used to sing Beatles songs together into the tape recorder I’d gotten for my bar mitzvah. On the day that President Kennedy was shot, Peter questioned whether we should play ball after school. We did anyway, but I was impressed that he had the sense of decorum even to think about it. I certainly didn’t.

Peter was the one who explained sexual intercourse to me. He did a good job, too; the only point where his description got hazy was the exact location of that crucial part of the woman’s anatomy. (I remember having a vague notion that it was located an inch or two below the belly-button. ) But I had the general idea, and by the time my father got around to trying to discuss the matter with me, I considered the subject firmly closed.

Now, my father and I never discussed anything. We didn’t talk about baseball, cars, politics, or religion. We almost never talked about how I was doing in school, or who my friends were, or what I wanted to be when I grew up. But most of all, we didn’t talk about sex. The very idea of such a discussion with my father was so improbable, so outlandish, that I literally could not believe what I was hearing the day he broached the subject. I was aware that discussions of this type took place in other families. But I thought of these father-son talks, when I thought of them at all, as a bemused anthropologist might ponder some curious rite of passage in a remote and primitive culture, like the circumcision of pubescent boys: all right enough for them, I supposed, and certainly very interesting, but wasn’t it nice to belong to a society that had evolved beyond such unseemly rituals?

Perhaps guessing how I might react and wishing to head off any opportunity for escape, my father waited until he and I were alone in his car. I know today that trying to talk about sex must have been every bit as difficult for him as it was for me. But he is a good man with a sense of responsibility, and he wanted to do his duty as a father. And I have to hand it to him, he tried. But I wouldn’t let him. I begged him to stop, shouted at him to stop, and finally he did. For my father and me, it was too late. The two of us had sat down years earlier and mapped out the borders of our relationship. Beyond them we could not, or would not, go. Or at least I wouldn’t.

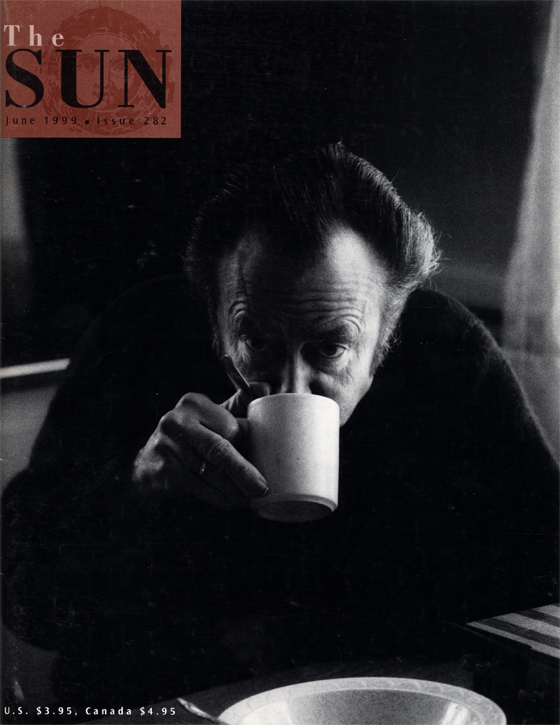

At the table, I take a good look at my father. Recently, his face has changed; the frail old man he will be is starting to emerge from behind the features of the middle-aged man he no longer is. A few years ago, after decades of smoking, he had quadruple-bypass surgery. He developed pneumonia (probably because of the cigarettes) and almost died. He was unconscious for days, his features gray, a big plastic tube coming out of his mouth.

I have a memory: It is Sunday afternoon, and my two brothers and I are eating Chinese food with my parents. For some reason, despite repeated warnings, my younger brother cannot seem to refrain from squeezing one of those little plastic packets of soy sauce. He just keeps squeezing away until, with a resounding pop, it finally bursts. Had he been holding the packet two inches from my father’s nose, he could not have scored a more direct hit. We sit in stunned silence, all the color draining from my brother’s cheeks while black rivulets of soy sauce run down my father’s face. Even my mother has nothing to say as we wait to see which of the half dozen emotions simultaneously evident on my father’s features will finally take hold. We greet the broad smile he eventually settles on with all the joy and relief of children welcoming the sun on a rainy summer day.

Another memory: I am playing with the neighborhood kids a few houses down when I see my father’s car pull into our driveway. It is springtime, and there are little puddles of slush and melted snow along the street. I run as fast as I can, right through the puddles. I run like the wind. I run to greet my father.

We are people of delicate constitution, my parents and I. We come together mindful of our wounds, and take what nourishment we can from our modest family rituals. For example, I know that, when our meal is over, my parents and I will file out to the parking lot. There will be a moment or two of awkwardness as we stand around my father’s car. Then my mother will give me a hug, and my father will shake my hand. I will, for the second time, thank my father for dinner, and I will assure my mother that, yes, I will definitely call before they leave for Florida for the winter. I will watch them get into their car and drive away. I will be aware of a heavy sensation in my chest and stomach. It will be the love that is easier not to feel, the love that presses down upon me like a weight.