I like to look at people’s skin. The way others might notice a man’s eyes, or the curve of a woman’s hip, I notice complexion and skin tone. It’s not the face I’m drawn to but the skin on forearms or around the collarbone, the wrinkles on knuckles — that’s real skin. For me, catching a glimpse of some hidden patch of skin is like seeing that person naked, like hearing his or her darkest secret.

I might know someone for a year or two before I see, really see, those spans of skin that absorb me, that tell me who this person is. Marie is a conventionally pretty woman with flawless, even-toned skin. It was two years before I noticed the little community of moles living on the side of her neck. They’d always been hidden by her beautiful blond hair. I suddenly felt as if I had glimpsed her deepest wound: each mole a hurtful disaster in her life. Another friend once revealed a large purple birthmark on his shin when he crossed his legs and his pant leg rose slightly. Immediately, he was an infant to me, a naked, helpless infant. I saw years of other children’s cruelty ahead for him. I had to look away.

The skin is revealed, good or bad, and I begin to understand something. I see skin as an enormous reserve of joy and pain. I despised my own skin for most of my life, and it gradually became my adversary in a great war.

My earliest memory of my skin is from age seven. Performing some splitlike stretch in gymnastics, I snuck embarrassed looks at the moles and freckles covering my legs. They seemed dirty, like a dirty secret. I was sure these dark spots signified some deeper, mean flaw within me, an indication that I didn’t belong, didn’t deserve to belong. Why else would I have them? I thought, with my perfectly reasonable child’s logic.

To my horror, my stretching partner noticed the moles and freckles, too. “What’re those?” she asked, with what I perceived as fully merited disgust. She confirmed my belief.

Other girls had normal skin: Beautiful. Unblemished. Smooth. I was transfixed by a long patch of perfect skin running down a leg or an arm. Even the girls who were as pale as larvae, even the one whose skin had an odd bluish hue, as though she were continuously suffering from hypothermia — at least they weren’t spotted. I coveted their clear skin the way I did summers and chocolate bars. I assumed my moles would go away only if I deserved for them to go away, only if I somehow became the type of person who fit the description of having clear skin: A sweet, bouncy girl with bright thoughts. A girl with a lollipop grin, a blond ponytail, and many, many friends. I believed that if I became this girl, I would earn clear skin, and my life would become lighter, happier. My mom and dad would love me more. I would not be so lonely. I would grow tall and beautiful. I would have a good life.

But I was not a sweet, bouncy girl. I was a seven-year-old military child afflicted with a crippling shyness. My family’s last move had been different from the others. Before, we’d lived in base towns flooded with transient families, but this conservative small town seemed to have been here since the beginning of time. I wanted to disappear, but I couldn’t not be noticed here. I was an only child being raised by atheist parents who were busy and rarely around. I had red hair, and my ears stuck out. I had a gap between my two front teeth and was constantly being admonished to “smile!” I had baby fat and few friends. (Strangely, when I look back at photographs of myself from this time, I see none of this wretchedness. I do not see the ears, the teeth, the baby fat. I do not see a girl who deserved the skin she hated. I see an adorable child. I also see a girl who is just dying to be loved, though no one noticed it, and she could never have revealed such a desire herself. It would’ve been unthinkable.) I was a lonely, serious child who longed to be a sweet, bouncy girl. And when I looked around for a reason why I couldn’t become her, the first thing I laid eyes on was my skin.

I began a self-mutilation circus, picking and cutting at the spots until they bled. At dinner one night, my mother zeroed in on my scarred legs, quizzing me as to whether I’d done this to myself, or whether the moles were bleeding and scabbing on their own, which apparently would have meant something terrible. When I confessed my shame, my parents looked at me with pity. I was sure they were embarrassed by me, their little spotted child with scabby legs and arms. They offered to have some of my moles removed by a dermatologist, but when I heard that the procedure involved “an electric needle,” I dismissed the possibility. Any pain I underwent would be at my own hands, not someone else’s. And certainly not if those hands held an electric needle, which I imagined to be at least three feet in length.

When I grew older, I learned that, as a redhead, I was supposed to have freckles — though that didn’t stop kids from teasing me — and I grudgingly grew to accept them as a side effect of my hair color. But the moles were different. The words even sounded different: Freckle sounds whimsical, funny, balloonish, like an afternoon party by the pool. Freckle, speckle. Mole sounds dark, burrowing, and somehow contagious: a time between midnight and 2 A.M., when all creatures are dreaming alone. I hated the way it stretched out in an unpretty baritone: mowwwwwlll. (To this day, I still cringe when I hear the word; it’s right up there with clit and pus.) As I became a teenager, I grew increasingly self-conscious about my skin and went from trying to remove the moles myself to trying to disguise them with dark tans. This was in the early eighties, when tanning was still fashionable and encouraged — even for people with moles.

As the years passed, my patience for lying in the sun vanished, and I made a timid attempt at self-acceptance. Still, with the men I dated, I opted for darkened rooms for passion, sure that too clear a look would send them running. I eventually found, to my chagrin, that they were often turned on by the prospect of playing “connect the dots.” (Each one thought this an original idea.) My body became a game of Twister. I felt like a freak in a circus tent alongside the goat boy and the bearded lady. So much for my attempt at self-acceptance.

As an adult, I’ve done serious battle with the notion of fitting in. My many moles are not the only feature that, to my mind, sets me apart from all other (surely happy) human beings. Thankfully, I’ve found fitting in becomes less and less important with age. Perhaps, as we all hurtle toward the end, we recognize that there’s at least one problem we all share. Yet fitting in still matters to me. I continue to feel slightly askew. The sweet, bouncy girl still shadows me, whispering in her melodious voice all the many ways I am not her and never will be.

Several years ago, my obsession with my moles was eclipsed by a new skin problem. I woke one morning to find my entire body, except my face, covered in an angry, itchy rash. Three different doctors told me it couldn’t be definitely diagnosed, but a dermatologist guessed that it might be parapsoriasis. It wasn’t the itching that drove me crazy so much as the fact that I’d developed yet another flaw in my already overly flawed skin. How could I possibly deserve this, too?

The unwholesome rash stayed with me for six months, during which time I avoided full-length mirrors. Five years later, I still develop little red spots here and there, and whenever I’m sick or stressed, the rash emerges again, though never as severely as it did the first time.

In the end, scorching ultraviolet-light treatments dried up the rash, but also burned my skin and left me with, of all things, scars. I found this exasperating, but at least I could look at my skin again and see only the pink of my flesh and the brown of my moles and freckles. I was no longer three-toned. I was suddenly grateful for average skin that simply displayed garden-variety moles and freckles.

With this new, grudging acceptance came the realization that I had, all these years, dramatized my skin. My moles were noticeable to an extent, but they no longer appeared leprous, as I had imagined them to be as a child. Somehow I had managed to endure my skin and build a relatively good, if slightly eccentric, life. And I had grown tall and — some told me — beautiful. But I was still lonely, unable to find my place in the world.

When I told my therapist about the rash, she observed that my skin was the layer that protected me from the outside world. Might it be significant, she suggested, that this layer had become a source of suffering for me? Could it be that perhaps my skin was trying to speak, a bit more loudly, about my disconnection from other people?

This was a highly annoying observation. Clearly, she was taking my skin’s side in this battle. Besides, I wasn’t ready to consider the complexities of the messages my body might be sending me. I’d been too embarrassed to explain to her my much more logical theory: that I didn’t deserve good skin. She was, however, a brilliant therapist with the most beautiful English accent I’d ever heard, so I was forced to consider what she said. Her questions repeated themselves in my mind, in her exquisite accent, over and over for the next several years. That accent was a password into my psyche, and the questions silently took hold of me.

The tentative acceptance of my skin following the rash lasted about a year. Then I moved to North Carolina, leaving behind my home of more than a decade, along with all my friends and all my comforts. I was alone again. Not surprisingly, I suffered this move through my skin. My familiar embarrassment returned. I covered up. I hid. I turned down invitations to go to the beach, even though I loved the ocean. I inspected my skin with a mean spirit, a serrated heart. And then I did something else: at age twenty-eight, I visited a dermatologist for the first time to have some moles checked. I don’t know why I waited so long. Most likely it was youthful faith in my immortality. The doctor shattered this faith in no time. Looking me over closely, she pulled out a blue ballpoint pen and circled three moles on my back as if they were incorrect answers.

“These are a priority,” she said with calm urgency.

A priority for what? I wondered. My shame and embarrassment? I was too afraid to think she meant anything else.

“We need to biopsy these right away.”

I was glad I hadn’t known in advance. As it was, my anxiety shot through the roof. I expected her to pull a three-foot electric needle out of a drawer any second.

I discovered, though, that a biopsy of a mole is a painless procedure — physically. Emotionally is another matter. I prayed for a sample as clean as the sky.

“We should know by next Monday if they’re malignant,” the dermatologist said, as though telling me when I could retrieve my dry cleaning. “And you should know that, based on the number of moles you have and your skin type, your chance for developing malignant melanoma in your lifetime is almost 100 percent.”

I called my mom. I cried. She called me “baby” for the first time in years: “Oh, baby.” And I felt my shame returning again. Now my skin was hurting other people, too. In my mind, it grew to the proportions of a universe, immense and bad-intentioned.

After that appointment, I viewed my skin with a wary eye, the way one would a dragon in a cave. This was it, finally. A doctor had confirmed it. My skin was my enemy, just as I’d suspected all along. It was not a part of me but a malevolent presence in my life. Long gone was any hope of ever becoming the sweet, bouncy girl. How could I even have imagined it possible? I spent the week following the biopsies sure I would die within a month or two, certain that this was the punishment I deserved for neglecting, for hiding, for hating my skin all these years.

The day before I was to get the results of the biopsies, I woke feeling simultaneously numb and raw. I lay in bed next to my boyfriend, Drew, and stared at the wall, quietly wondering what was ahead for me. Was my life about to change dramatically? Would there be more needles and digging, followed by a final diagnosis and a slow, painful death? I was sure that the moles had been spotted too late.

Dredging around in these thoughts, I hadn’t noticed that Drew was awake beside me. We had been living together for a year. When I’d told him, very casually, about the visit and the biopsies, his reaction had been a mix of shock and quiet awe. We hadn’t spoken of it again. I wondered: Was he afraid, too? Or was he convinced it would turn out to be nothing?

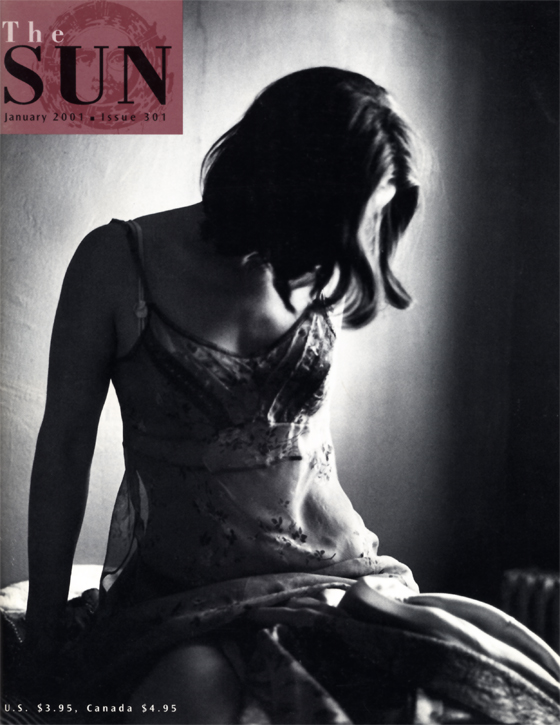

While I was considering these possibilities, Drew moved closer; he wanted to make love. Unsure of exactly what I was feeling, I silently agreed. We lay on our sides, with him behind me, and I realized that he could see the biopsy wound from the most troublesome mole, on my left shoulder blade. I wondered what it was like for him, making love to me and seeing not my face but, instead, evidence of my uncertain future. This was a complicated passion, a story of love and pain and possible death swirling around us like smoke. I began to cry quietly. Being too terrified to tell Drew just exactly how frightened I was had cracked open a deep well within me, a loneliness the depths of which I had never felt before. Tears jumped down my cheeks as he gently moved against me, and I thought, This is such an awful scene.

“The news,” the dermatologist told me, “is mixed.” There was no cancer, but the cells were “abnormal,” which meant I would have to watch the areas carefully in case “pigmentation” returned. That would spell trouble.

“You’ll need to come back every six months so we can check everything,” she said. “As long as you keep coming in, you’ll probably be OK.”

Although her intent may have been to make me a vigilant skin watcher, her warning filled me with swarming hysteria, which set me apart even more from everyone else. I felt I’d been handed a death sentence. And it made perfect sense. My body was tired of my self-hate, my insults, my constant blaspheming of it. One day soon, it would simply leave me.

A year passed, and though my fear remained, it gradually abated. My body, it seemed, would be around, at least for a while. I was even thinking about vacationing on the coast. But first I asked my dermatologist’s opinion. “It’s fine,” she said, “just don’t go out on the beach during the day. I don’t. I sleep or go shopping! My family thinks I’m a party pooper, but I’m safe, and that’s what’s important!”

Suddenly, her alarm, her nervousness, and her very “safe” lifestyle made me want to slather myself in baby oil, lie on a sheet of aluminum foil, and roast like a Thanksgiving turkey. I couldn’t imagine living the way she did: always covering up, always afraid, always avoiding. I was unwilling to follow her instructions any longer. Moderation, perhaps, but total avoidance, never languishing in sunlight?

And then it hit me: That was what I’d been doing all along. Avoiding. Covering. Fearing. I hadn’t been running from the sun, though; I’d been running from people. I’d been avoiding close friendships. I’d been afraid of love, deeply. I had covered my soul for fear that no one — including me — would ever find it acceptable. I had lived my entire life as if my body were a suit I hadn’t chosen — one I would never buy for myself and would accept only if given to me by my grandmother (and even then, I’d give it to Goodwill). I had occupied this suit very little, become numb to it whenever I could. And worst of all, I’d become small in it, as if I hadn’t earned anything better to cover my fearful soul.

I left my hysterical dermatologist and found one who recommended a calm but steady gaze on my skin. He begged me not to worry. He said I would be just fine. He promised he would examine me every six months. He told me not to look at my moles every day, because that would make it more difficult to detect changes in them. Instead, he suggested, why not look at my skin every three months or so?

Look at my skin only every three months? It took me weeks to adjust to the idea. And I did slip, sneaking a peek now and then. But mostly I felt jubilant, as though I’d been released from prison. A prescription not to focus on my skin — I couldn’t imagine anything better. And he’d promised that I would be fine. I know he meant that my skin, my health would be fine, but I took it to mean something more: I would be fine. I was OK. My skin was not my enemy but simply a part of me that asked to be checked on occasionally, to be looked at. And taken care of.

Slowly, without even realizing I was doing it, I began to reveal myself. I showed my skin to the sun and the clouds, to lovers and friends. Outside and inside, I began to glow.

Not all my problems have been solved. I am still very shy. I still feel set apart from most people. I am still unsure of my worthiness. But now I give myself a chance to get close. I have learned to peel off the layer that separates my soul from the world. It is an invitation. My sleeveless shirts, my shorter skirts are saying, Look at me; come closer; love me. This skin is beautiful, and it is all that separates me from you.