In discussions of justice in America, talk of punishment and retribution dominates. There is little interest in offering criminals, even juveniles, a second chance. But Joseph Rodríguez’s story makes a strong argument for the possibility of redemption.

As a teenager in the late sixties, Rodríguez was incarcerated at Riker’s Island in New York City for harassment. After his release, he became a heroin addict — and then a thief, to support his habit. He was sent back to Riker’s for robbing a small grocery store. He came out a second time determined to beat his addiction.

Rodríguez went to a free methadone clinic and moved out of the neighborhood where he’d gotten into trouble. The Family of Man, a book of photographs by photographers from around the world, inspired him to buy a camera. He took a workshop at the Brooklyn Children’s Museum and started taking pictures everywhere he went — until he got mugged, and the camera was broken. Undeterred, he attended New York City Technical College through an affirmative-action program and later went to the International Center of Photography, where he cleaned darkroom sinks in exchange for a chance to attend classes.

Rodríguez is an award-winning photographer whose work has appeared in Time, Life, and National Geographic. His book East Side Stories: Gang Life in East LA (powerHouse Books) was a critical and popular success in a genre — photography books — that rarely garners much attention. He still lives in Brooklyn, where he grew up.

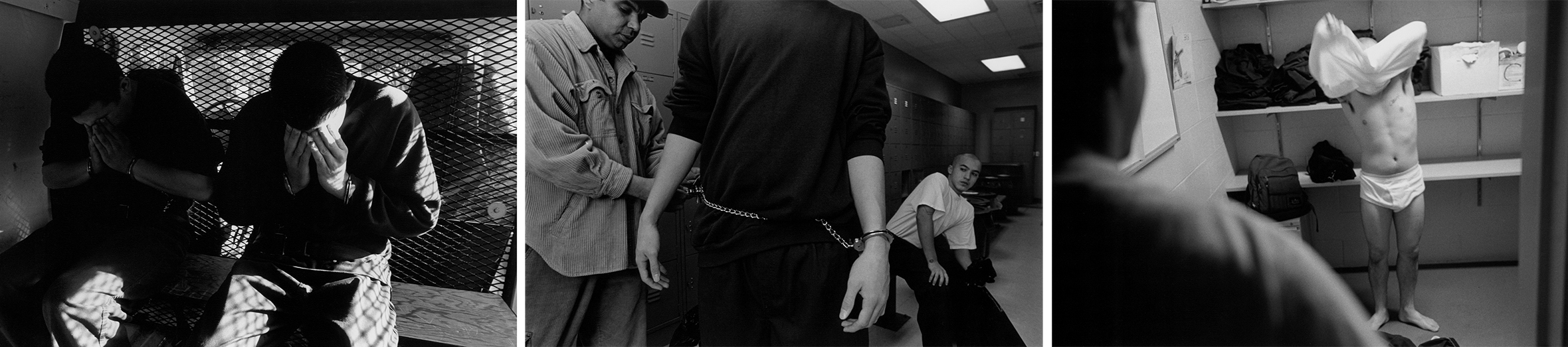

Rodríguez’s latest book, Juvenile (powerHouse Books), documents the lives of incarcerated youths in California’s juvenile-justice system. But Rodríguez doesn’t just photograph the boys and girls behind bars. He follows them back into their communities as they try to find jobs, get an education, and raise their children. Many fail because they can’t stay off drugs, are overwhelmed by college-admissions paperwork, or don’t know you have to call in sick when you can’t show up for a job.

Rodríguez’s photographs demonstrate how precipitously close to disaster these young people live. “All kids make mistakes,” he says. “The difference is that if you’re in the middle or upper class, you have a wider safety net to catch you when you fall.”

Thanks to Maria Finn Dominguez for bringing the work of Joseph Rodríguez to our attention.

— Ed.

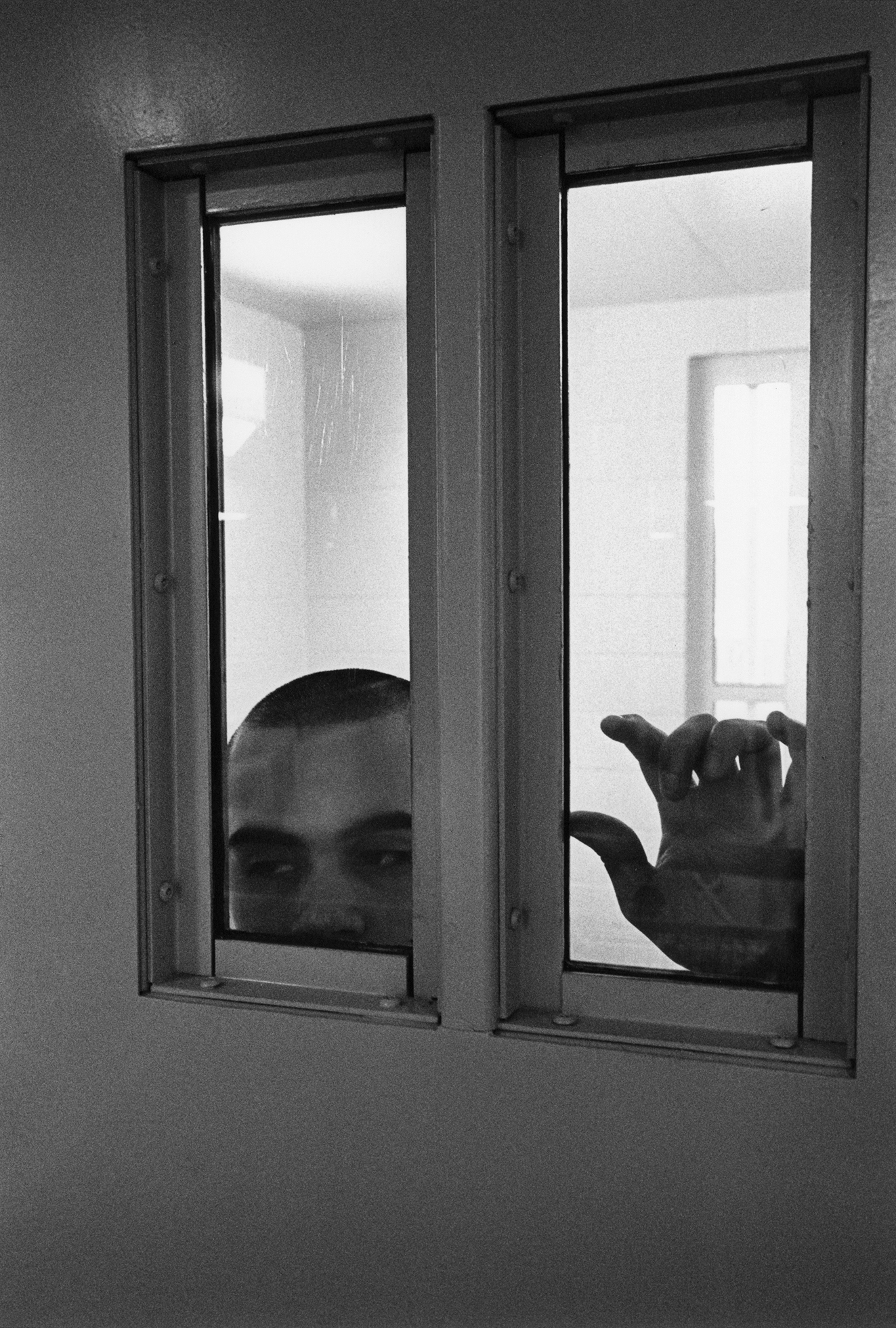

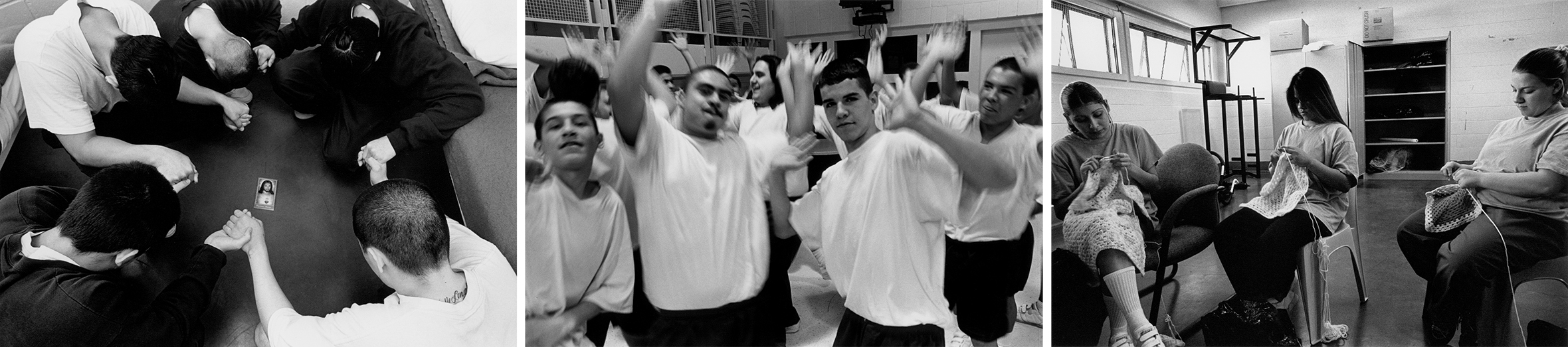

Katrina, age sixteen, 2000: Katrina is in San Jose Juvenile Hall for a probation violation. She’s been incarcerated once before, for auto theft and evading the police. Her father is in prison, and she doesn’t know where her mother is. She has lived with foster families since she was six. She is waiting to be placed in a group home.

Inside Santa Clara County Juvenile Hall in San Jose, California.

Sovanny, age seventeen, 1999: Sovanny is in the maximum-security B-8 Unit at San Jose Juvenile Hall. He threw a rock at a car, and the rock struck a rival gang member in the head, seriously injuring him. He is waiting to find out whether the injured boy will live.

Both of Sovanny’s brothers are also in jail. His parents emigrated from Cambodia in 1981. When they arrived in America, the couple had no friends and no formal education and spoke no English. Schoolteachers and police told them to stop using corporal punishment on their children. They didn’t know how else to reprimand their boys, so they stopped disciplining them altogether.

Inside Santa Clara County Juvenile Hall in San Jose, California.

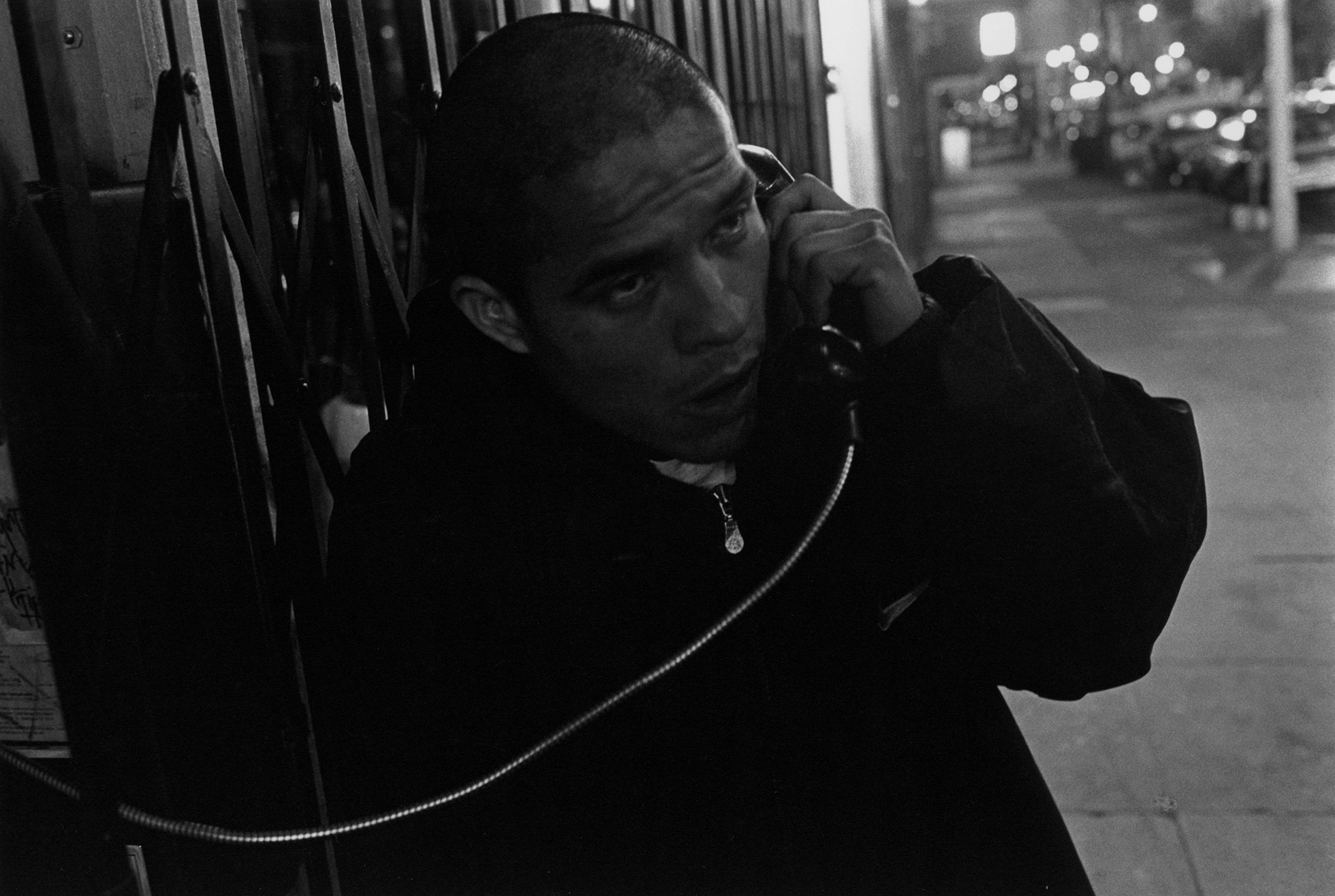

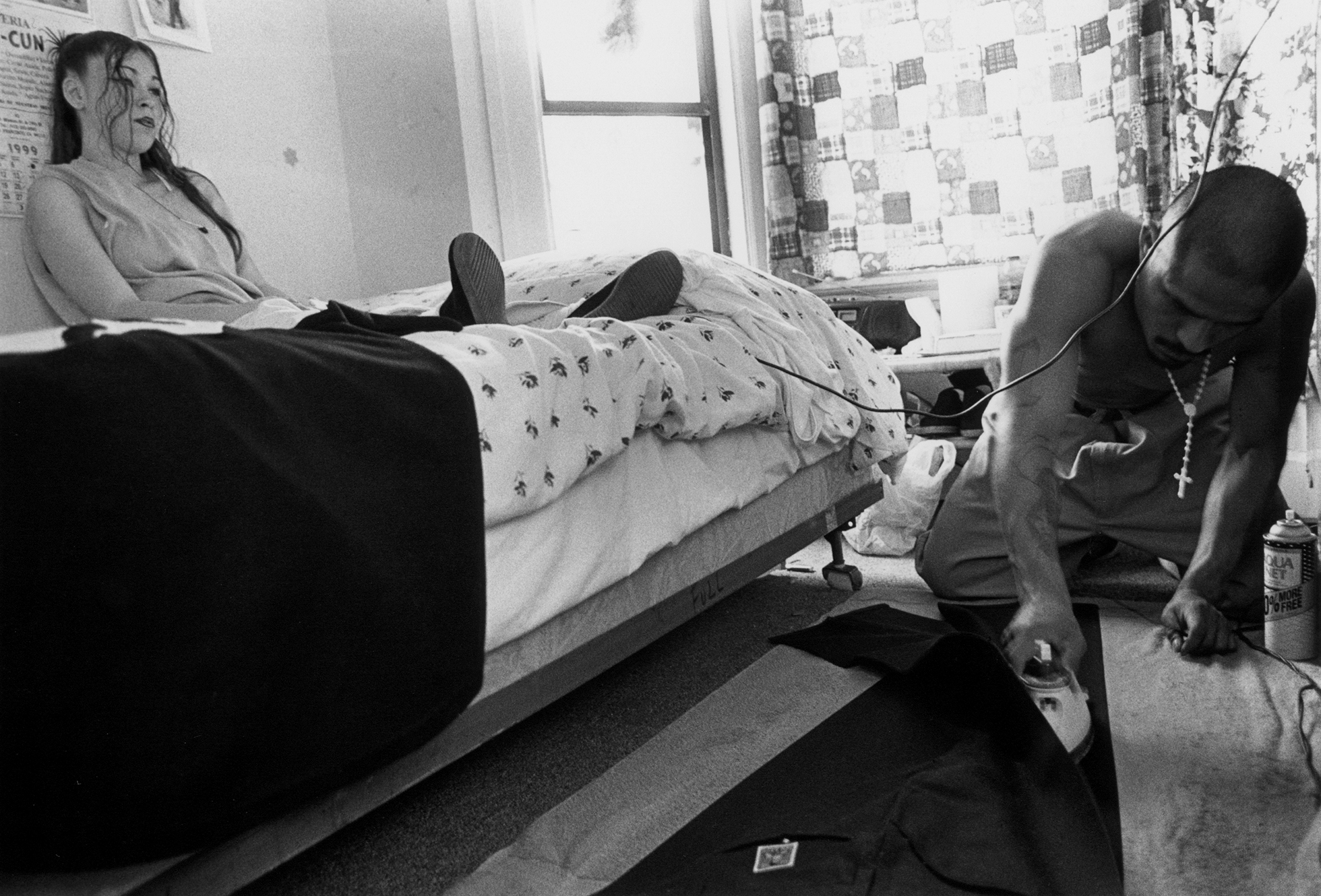

Gregorio, age nineteen, 1999: Gregorio left Mexico to escape overwhelming poverty. He crossed the border on foot and wandered in the desert for seven days, eating only cactus. After picking strawberries for fifteen dollars a day in Chula Vista, California, he came to San Francisco and joined the 19th Street Gang, a division of the Sureños (“Southerners”). Gregorio tries to phone his girlfriend, Miriam, at her mother’s house, but she’s not at home.

For a while, Gregorio and his girlfriend, Miriam, lived in a cheap hotel room in the Mission District, but she returned to her mother’s house, and he went back to living on the street.

Inside Santa Clara County Juvenile Hall in San Jose, California.

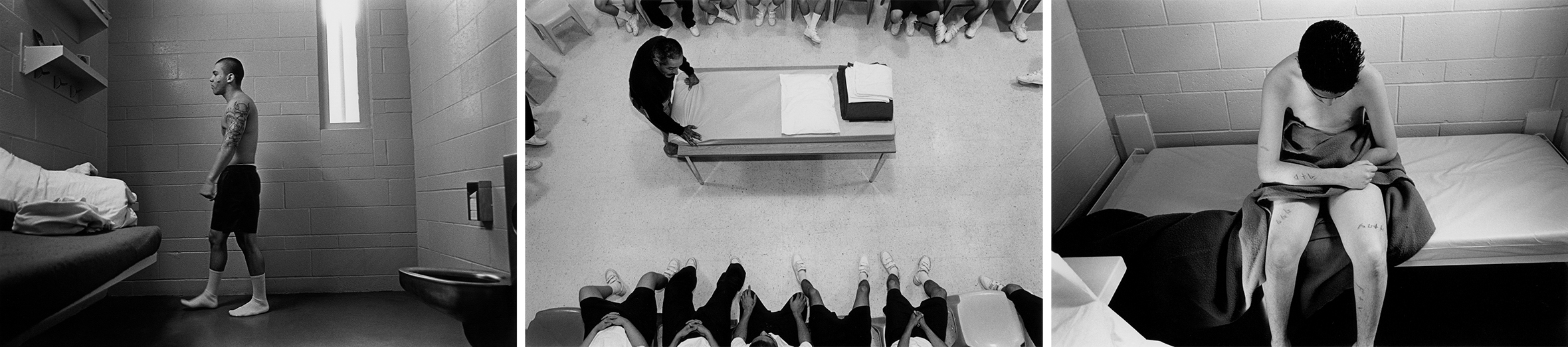

Lance, age twenty, 1999-2000: Lance began his criminal life at the age of thirteen. His mother, a stripper, says she was so overwhelmed by her own problems that she didn’t see what was happening to her son. He scored high on IQ tests and was also labeled “severely emotionally disturbed.” He was arrested at fifteen for kidnapping and murder. At that time, fifteen-year-olds could not be tried as adults. Lance had the opportunity to redeem himself within the juvenile system. As part of his rehabilitation, he took part in “The Beat Within,” a writing workshop for incarcerated minors. Once out of the system, Lance moved to San Andreas, California, and found work as a landscaper.

Lance now has a wife, Sarah, and two children. He still writes poetry.

Inside Santa Clara County Juvenile Hall in San Jose, California.

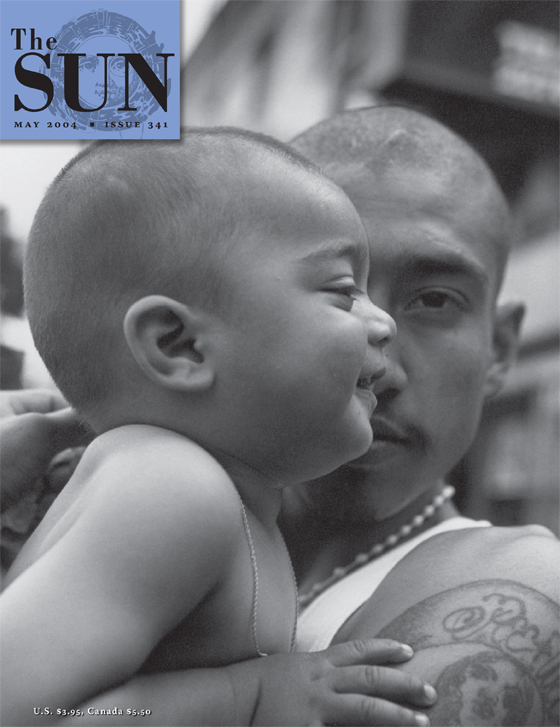

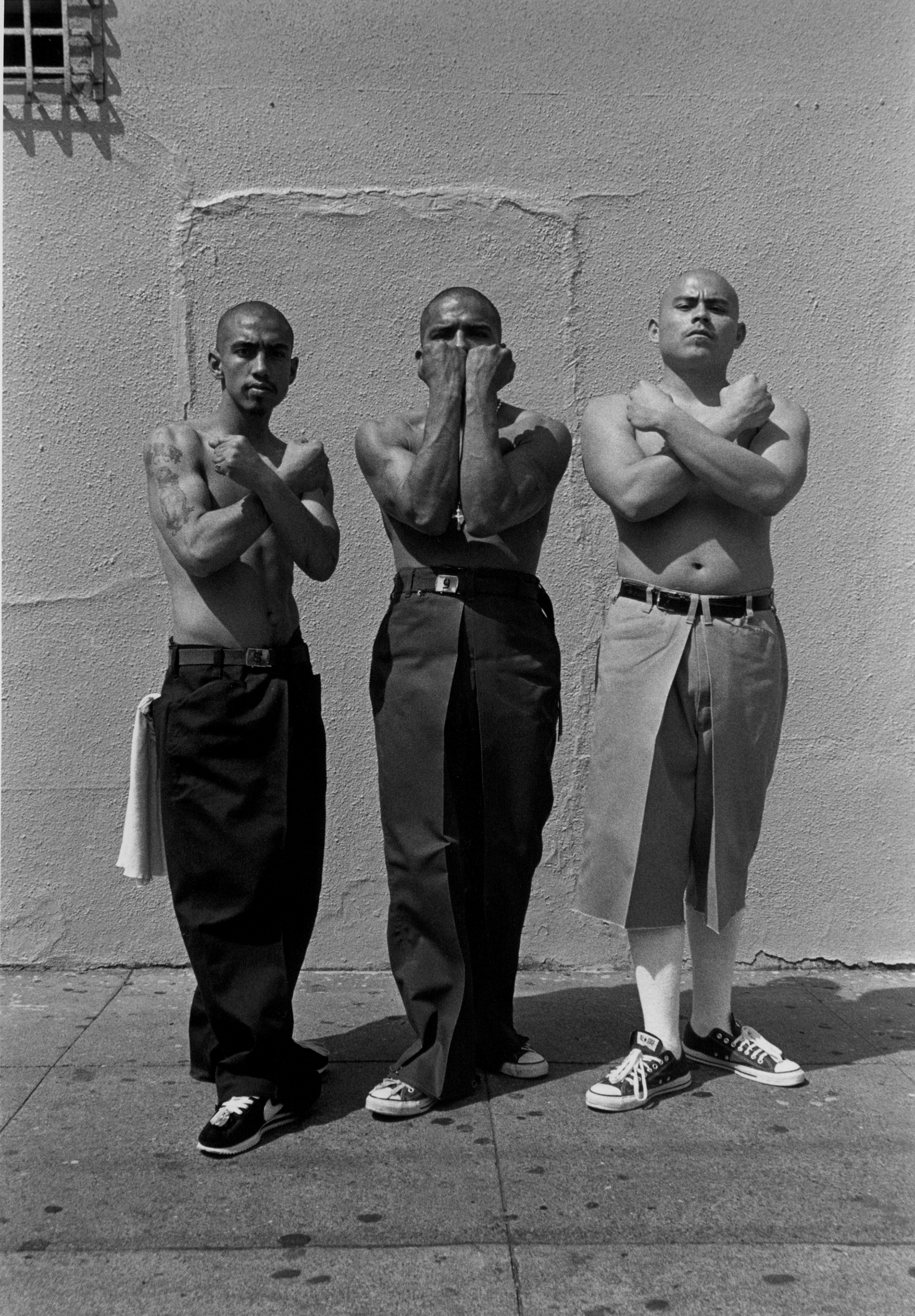

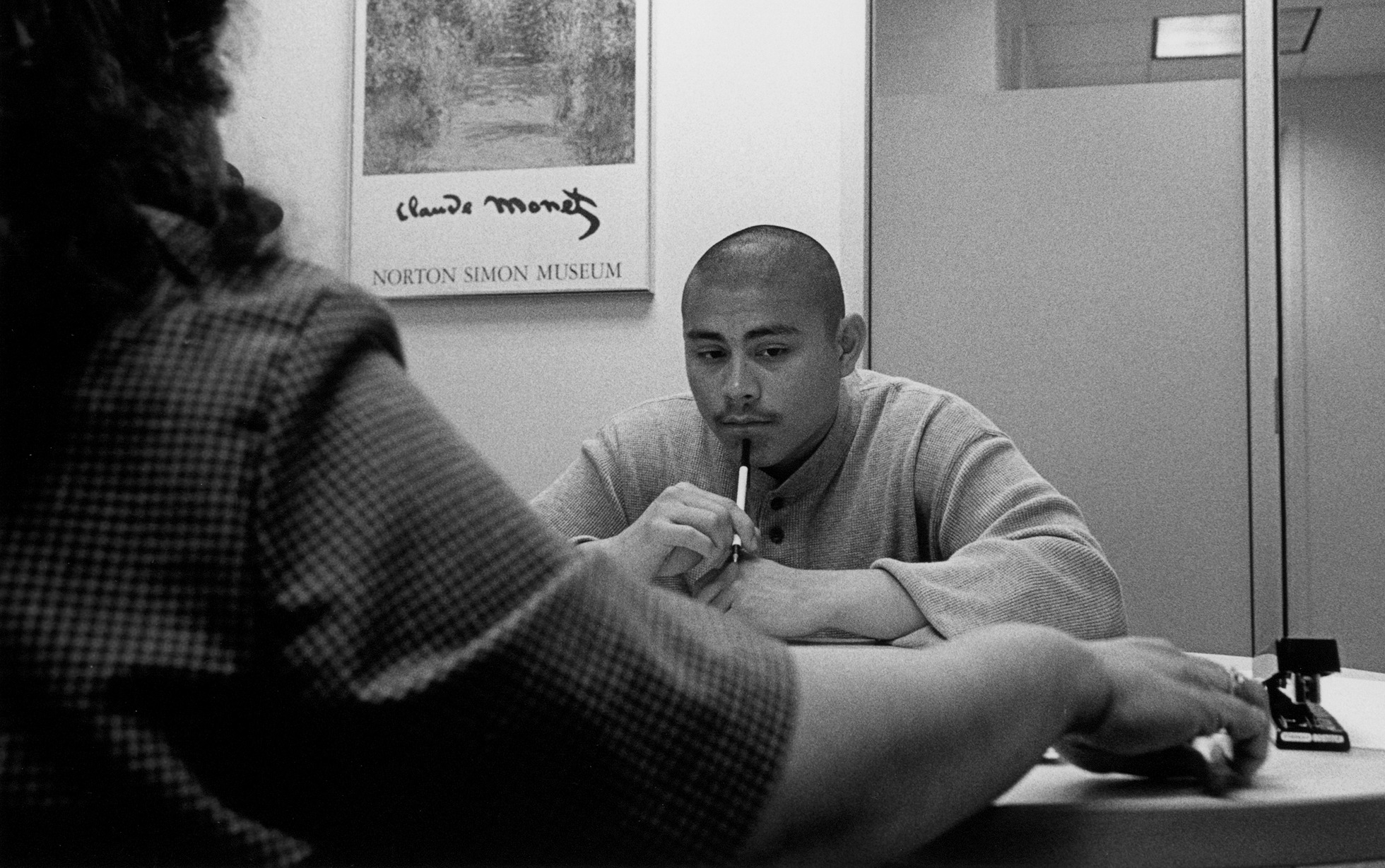

Carlos, age nineteen, 1999-2000: Carlos (with white socks) came to the U.S. from El Salvador and was drawn to the fast money of dealing drugs.

When his girlfriend had a baby, Carlos decided to change his ways. He wanted to attend business college, but was discouraged by the paperwork and the cost of student loans.

Carlos got a job as a waiter instead and is trying to stay away from his homeboys in the 19th Street Gang.