Remote as the moon and yet more remote.

— Peter Mulvey

I was fucking a near stranger in northeast Chicago when my mother died. His name was Jonathan. He was tall, long-limbed with enormous hands and prematurely gray hair, an activist who lectured on “the struggle” so genuinely I almost believed him: that we would win this, whoever “we” were, whatever it was.

We had spent the afternoon at the F15 antiwar demonstrations. It was bitterly cold; I wore thick gloves and balled my fists in my coat pockets, and still my knuckles ached. The crowd was small, about five thousand, compared to the five hundred thousand in the streets back in New York. Jonathan knew many of them, as I would have at home. I felt a flush of relief to be among strangers, to be anonymous among an anonymous, indifferent crowd. I let the march carry me up Devon Avenue, stepping in time with the drums and shouting with the chants, watching my breath cloud on the air.

It was a lousy world. My country was preparing to kill as my mother was preparing to die. And in the smaller terrain of my personal life, my lover and I were on the skids. He wouldn’t use condoms, and I wouldn’t fuck him anymore without them. We’d spent my last evening in New York glaring at each other over beer mugs, then stumbling to his apartment and sleeping with our backs to each other, like two spoons that don’t belong in the same drawer.

After the march Jonathan and I got a ride from a girl named Tracy to a Mexican restaurant near his apartment in Andersonville. We had garden burgers, salads, and Cajun fries dipped in mustard and ketchup as we talked about “the movement” and where we thought it was headed. Then he invited me back to his place.

There is a certain kind of sex between strangers: meaner, greedier, more direct. I quickly learned the flat planes of his body, the long pelt of his torso, his small, round ass more like a girl’s than a man’s. We didn’t kiss on the mouth. His hands were always exactly where I wanted them to be, and yet I always wanted them somewhere else, everywhere. I wanted him to fuck me, but he held off. I want you to be ready, he murmured. I want you to want it. I squeezed him and he groaned. Do you have condoms? I whispered. He reached behind the bed and scooped up a handful, and I nearly came right then from sheer relief.

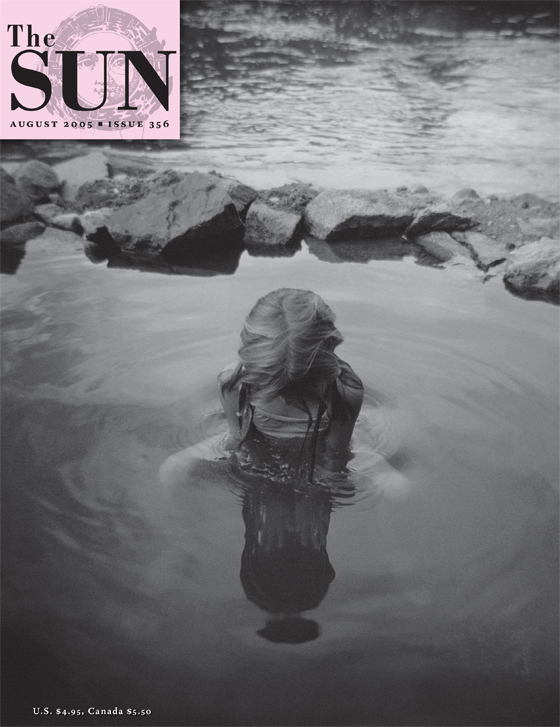

Afterward, I laid my head on his flat chest, his large hands warm against my back. The radiator roared like the sound of water pouring into a bath, filling the small room with warmth. Dusk edged the curtain, tinting the walls a faint and hazy blue. I felt cushioned by the mattress beneath us, the blue wall of sound around us, the rush of traffic beyond, the closeness that asked no questions. I felt myself drifting, cosseted, toward the best sleep I’d had in months, and dropped into it as if into a heated pool.

I knew myself to be cuddling with my mother; as a child, but also as my adult self. Maybe it’s because he’s a woman, I thought sleepily, smiling to myself. Wait, that’s impossible, I thought, jerking awake. Jonathan’s eyes blinked open. I wanted to tell him, rehearsing the words in my head. I dreamed you were a woman. . . . I dreamed you were my mother. . . . But that wasn’t it, exactly, either. . . . I raised up my head and kissed him on the mouth, and he kissed back.

We were fucking again when I glimpsed the indigo numerals of his alarm clock: 6:00. Wow, 6 P.M. exactly, I remember thinking.

The next morning my sister called me at the friends’ house where I’d slept and told me that our mother had died the night before at 6:55 P.M. Eastern Time — or five minutes to six in Chicago.