For four consecutive Saturday mornings when we were in ninth grade, Brian Henderson and I went to a second-floor office above the pharmacy downtown to breathe. We woke at eight o’clock. We could not brush our teeth or eat. Our mothers took turns shuttling us to and from the squat brick building, where we assembled with a couple of dozen others — some high-schoolers, but mostly college kids and down-on-their-luck adults — in a low-ceilinged waiting room with a black-and-white tile floor and a bank of windows overlooking Hudson Road. Brian and I signed in and took numbers, which we pinned to our shirts. Then we each took a two-inch section of clear plastic tubing from a box by the door, and we sat in folding chairs along the wall to wait. Brian always brought the latest issue of Sports Illustrated (his dad had a subscription), and I brought the sports section from the Saturday paper, and we sat next to one another, not actually talking, but definitely there together — two boys who’d known each other since fourth grade.

At nine o’clock a door at the opposite end of the waiting area opened, and a woman emerged wearing a white lab coat and carrying a clipboard, from which she read numbers that corresponded to the numbers pinned to our shirts. Her name was Mrs. Boland, but Brian called her Dr. Boland, because of the lab coat, and because he harbored a fantasy about a “physical examination” behind the closed door, which was marked Private. She seemed plain to me, with pale skin and a too-thin frame, but she wore skirts above the knee, and maybe that was what got to Brian, the way shirtless men with smooth chests would eventually get to me. When Mrs. Boland called your number, you took your plastic tube to one of four panels of plywood that had been erected against the far wall. In each was a hole slightly larger in diameter than the tube. Through the hole you could see a man’s nose and mouth, and a clipboard on his lap. You bent down with the tube pressed to your lips. You inserted the tube in the hole. And you breathed.

At 9:15, after everyone had breathed into a hole, Mrs. Boland disappeared behind the door marked Private and came back with a tray of food. She set the tray on a folding card table and read numbers again from her clipboard. As those numbers were read, half of us went to the card table and took a piece of food and ate it. Sometimes it was a square of pepperoni pizza, sometimes a hoagie sliced in inch-wide slivers, each placed on a paper napkin. The ones whose numbers weren’t called stayed in their chairs and read whatever material they had brought with them.

At 9:30 Mrs. Boland again read all the numbers from her clipboard, and when your number was called, you again took your tube to one of the four sections of plywood and bent down with the tube pressed to your lips. You could see a nose, a mouth, a clipboard. You inserted the tube in the hole, and you breathed.

At 9:45 Mrs. Boland returned with a tray of plastic cups, the sort hospitals use to deliver medicine to patients. Each cup contained a breath mint. Here was where it got tricky. Half of those who’d gotten food got a breath mint. Half of those who hadn’t gotten food got a breath mint. The rest got no mint. So we were divided into four categories:

1. Food, breath mint.

2. No food, breath mint.

3. Food, no breath mint.

4. No food, no breath mint.

The breath mints were chalky blue discs the size of a nickel. Mrs. Boland would remind us, “Suck them; don’t chew” — a refrain that got Brian’s attention. “Ooooh,” he’d say under his breath. I tried to follow instructions, but after a minute or two of sucking, the discs became as thin as Communion wafers, and you couldn’t help but chew.

At ten Mrs. Boland returned again and read all the numbers on the clipboard. When your number was called, you took your tube to the plywood and breathed.

At 10:30 everyone breathed one last time, then collected fifteen dollars cash from Mrs. Boland. Brian and I took our money across the street to the Hudson Deli, where we bought a roast-beef sub for four dollars, and we sat on the curb, thirteen dollars each in our pockets, and split the sub and waited for his mom to pick us up.

The Hendersons had moved to Maryland, into a house two doors down from ours, when Brian and I were in fourth grade. My older sister Soley was hanging out with her friend Karen Maddox when the moving van arrived. Soley poked her head in the door and said to me, “Will, they’re here.”

New neighbors were a big deal. Did they have kids? What age? Boys or girls? I wandered outside as the Hendersons piled out of their station wagon. There were Mr. and Mrs. Henderson, their long-haired mutt Prince, little Kevin, who was in kindergarten, and Brian. Soley let out a sigh, her hopes for a girl deflated, but I walked down to the street, where the movers were opening the door to the van. The Hendersons were standing in their new driveway, stretching, and their dog was barking. “Will’s got a new friend,” Karen Maddox said, and the two girls giggled.

Brian was everything you’d want a new neighbor to be — that is, if you were a fourth-grade boy obsessed with sports. He’d moved here from Minnesota and had a football autographed by the Vikings squad that had made it to Super Bowl IX. Mr. Henderson had played wide receiver at the University of Illinois and had tried out with the Bears before deciding on law school. Their second week on Newington Street they put up a basketball hoop beside their driveway, which was built for two cars, unlike ours. I was over there all the time, shooting baskets with Brian and his dad. Mr. Henderson was six-foot-three and could dunk. Once, he shot a basket from their front porch. We dubbed it the “four-point shot.” Brian tried the same shot and made it. When I tried, the ball got only as far as the foul line.

And so it went with Brian and me. He was great at sports; I was only average. While I played in the local recreation leagues, Brian was in Little League, and his team made the regional finals in New Jersey. He played basketball on a team that won tournaments in Baltimore. And he played football, while my parents would let me play only soccer.

By sixth grade Brian moved in a different universe than I did. He carpooled to practices with kids I didn’t know, and if I was shooting hoops when he got home, he wouldn’t join me. If he was shooting and I joined him, he would tolerate me for a few minutes, then head inside, saying it was time to do homework. I eventually took the hint and stopped going over. Brian became like any other jock at school who wouldn’t give me the time of day.

Of course, middle school is also when most boys become interested in girls. Brian had a girlfriend in seventh grade, and another one in eighth. I remember riding my bike down Newington Street one afternoon and seeing Brian in his driveway, a basketball tucked under his arm, chatting with my sister and Karen Maddox. The girls sat on a low section of the brick wall that led up to his porch. I slowed my bike, hoping for an invitation to join them, but only my sister waved. Karen sat on her hands and looked at me as though I were the mailman driving by. For Brian I was invisible. He began to dribble through his legs, in figure eights, his gaze fixed on an imaginary defender. I coasted up my driveway on my ten-speed and dismounted. Brian tucked the ball back under his arm. Karen Maddox laughed.

Brian and I breathed together from the end of April to the end of May, a lull for him between sports seasons. It was my mom who got me the gig. She knew someone at church who knew someone involved in the product study. I had been cutting lawns, but this paid better and was easier. Brian’s mom heard about it from my mom and thought it would be good for Brian to make some of his own spending money.

The first week my mom made me sit in the back seat. “Brian’s legs are so long,” she said. He was in the midst of a growth spurt, and within six months would grow four inches and rise from shooting guard on the JV team in ninth grade to forward on the varsity in tenth — the only tenth-grade starter that year. In fourth grade we’d been the same height, but now my eyes came only to his chin — if I was able to get that close to him.

My mom started the car as Brian came out his front door. He glanced in the back seat and then got in on the passenger side. “Hello, Mrs. Brashears.”

“Hello, Brian.” She shifted into reverse.

He turned his head sideways. “Hey, Will.”

It was the first time he’d said my name in years. My heart jumped. “Hey, Brian.” I was trying to sound casual, but I rushed it.

While he gazed out the front and talked to my mom about his family, I stared at his shaved neck and the way his freckles bunched at his shirt collar.

My mom drove into town and dropped us off. We signed in and got our numbers and our clear plastic tubes. Then we met Mrs. Boland. Brian stood and extended his hand to her, and she took it. When our numbers were called, we each went to the plywood, bent down with our tube to our lips, placed the tube into the hole in the wood, and breathed.

There was a rhythm to these Saturdays: the greetings, the drives downtown, the numbers, the plastic tubes, the sports sections, the Sports Illustrateds, Mrs. Boland with her lab coat and short skirts, the pizzas and hoagies, the mints, the breathing through the tubes, the anonymous men with their clipboards on the other side of the plywood, the cash, the sandwiches afterward from the Hudson Deli.

The first week I got pizza and no mint. Brian got a mint, but hadn’t gotten pizza. “Breakfast,” he said, popping the blue disc into his mouth. “How was that pizza?”

“How’s that mint?”

“You are so lucky,” he said.

“Remember what Dr. Boland said: ‘Suck it; don’t chew it.’ ”

“Oooh,” he said. “I love that.”

Afterward we walked outside into the bright sunshine. “I’m rich,” Brian said. “Rich and hungry.”

I followed him across the street to the deli. We bought the sub and sat on the curb and each took half. His mom was late. “Hey.” He touched his cheek next to his nose. “Am I getting a pimple? It feels like I am.”

I looked where he was pointing. His cheek was red. “Move your finger,” I said.

He lowered his hand.

I ducked my head and leaned my face in front of his. “Maybe,” I said. “I don’t really see it, though.”

“You don’t see it?”

I shook my head.

“Cool,” he said. “Now scoot away, pepperoni boy. Your breath is foul.”

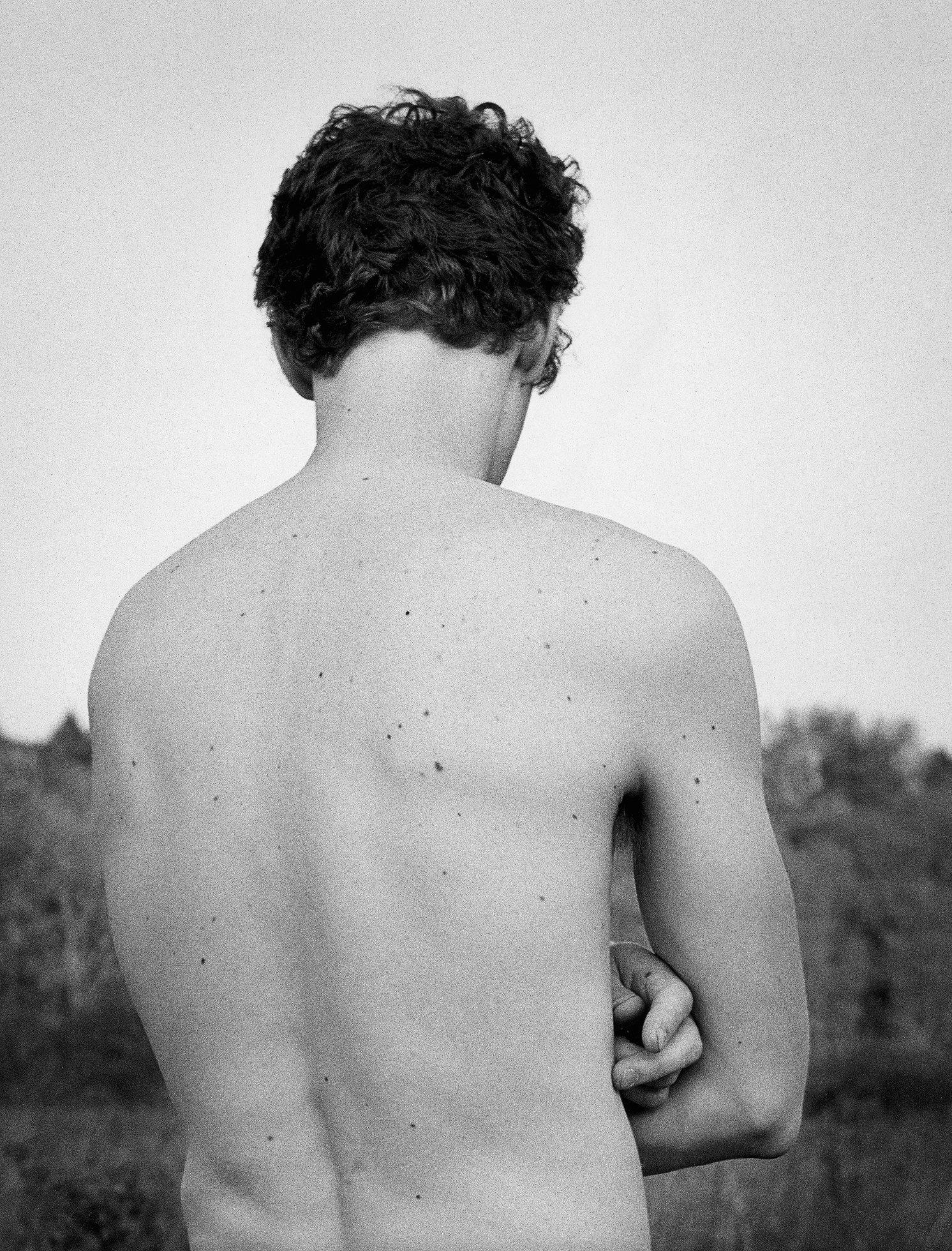

Before Brian and I had begun to breathe together, I’d developed my first crush, on a boy named Peter Worth. Peter and I had two classes together: English and science. In English our seats were arranged alphabetically, so Peter and I sat at opposite corners, but in science Mr. Connor let us sit wherever we wanted, “so long as it’s at one of the tables in this room.” The lab tables had thick black countertops, and each sat two students. In the confusion that followed Mr. Connor’s proclamation, Peter and I wound up together at a table in the back. Peter was new to our school, so maybe we were drawn together by our status as outsiders. Maybe I was merely attracted by his hair, which was as black as the countertops and clung to his scalp in loose, thick curls. I didn’t know I was gay then. Maybe I was wondering, but I didn’t know.

The crush began later, in March, when I noticed that Peter’s eyelashes nearly touched the lenses of his protective goggles. We were standing over a beaker that we’d filled with liquid and placed over an open flame. His hair had grown unruly, and he would make it stick up at odd angles with a hairbrush he kept in his back pocket. He loved science fiction and playing the mad scientist. We were expecting the liquid in the beaker to begin to smoke, and possibly even explode. We leaned our heads forward, together, to get a closer look.

The next day Peter and I sat at our table in the back, listening to Mr. Connor’s lesson about food preservatives. We had our spiral notebooks open in front of us, pens in our hands. Our elbows nearly met. I felt the heat from his arm on mine. I slid over a fraction of an inch, and our arms touched. He stiffened, or it felt like he stiffened. Maybe it was me. His arm was still for a moment. Then he stretched and scooted his chair back.

The following week we were assigned a lab on single-celled organisms. At the start of class I collected our slides, but Peter was missing. I scanned the room and spotted him with Rick Roach and Jonathan Freeman, who were lab partners and played JV basketball with Brian Henderson. They were talking and laughing. I don’t know what came over me then. I became possessed by the singular desire to wrench Peter from Rick and Jonathan and bring him back to our table with me. I grabbed the first weapon I could find, a textbook — a four-hundred-page hardback — and I snuck up behind Peter and clobbered him on the head with it. He fell forward into Rick Roach, then wheeled around.

“It’s time to go,” I said. “We’ve got to —”

“What the fuck is wrong with you, freak?” He snatched the textbook from my hand and reared back with it. “I’m going to kick your faggot ass.”

“Boys!” Mr. Connor had emerged from his office.

“He smacked me with this book,” Peter said.

“Both of you,” Mr. Connor said, “in my office.” He waved his hand at the rest of the class. “Start the lab.”

Mr. Connor’s office had just enough room for a desk, two chairs, and a metal bookshelf. “Sit down, please.” He closed the door. A wall of windows faced the classroom. The blinds were down, but the slats were open.

Peter sat in the chair facing the desk. Mr. Connor motioned for me to sit in his chair, behind the desk.

“I will not tolerate physical or verbal abuse in my class.” He placed his fists on his hips. “What happened?”

“Ask him,” Peter said.

Mr. Connor looked at me.

For a moment I thought I might cry. “I wanted to get started on the lab.” I turned to Peter, who was staring at the wall behind me. “I’m sorry.”

He blinked. Our eyes met, and this time I looked away, at the bookcase filled with files and Mr. Connor’s texts from college.

“I don’t want to have to change your lab partners,” Mr. Connor said, “but I will.”

“It’s not necessary,” Peter said. He was looking at his hands folded in his lap. A tremendous sense of gratitude welled up within me, but I managed to choke it back and contain it. I said again, “I’m sorry.” I would be more careful in the future.

At our third breathing session, Brian and I both ate the square of pizza and the mint. At ten o’clock we breathed. When he sat back down and picked up his magazine, he asked, “What do you think about those guys?”

“What guys?”

He lifted his chin. “The ones in the box. Have you ever seen one?”

I looked at the plywood, the empty holes. “Only their hands and noses and mouths.”

“But never their eyes!”

“No,” I agreed, “but I haven’t been looking for them, either.”

“What a weird job.”

“Is it any weirder than sitting here, waiting for your number to be called so you can breathe on them?”

“Definitely,” he said. “They’ve probably been trained in odorology or something. We’re just the rats they’re evaluating. Besides, I’d rather be pitching than catching, if you know what I mean.”

“Maybe they get paid more than we do,” I said.

“I hope so.” He turned a page in his magazine to let me know that the conversation was done.

A little later we were sitting on the curb in front of the Hudson Deli, eating our sandwiches and waiting for Brian’s mom. We had one more week of breathing. Then I had a summer of cutting lawns up and down Newington Street, of hanging out alone at the pool, of boredom in my basement. He had a summer of Little League and playing baseball up and down the coast. Then, in August, it was football practice, twice a day under the hazy sky. The Hendersons belonged to the pool, and I would sometimes see Brian’s brother Kevin, now in fifth grade, playing underwater tag with his friends. But I would never see Brian, who was too busy, I supposed, with sports.

Now Brian widened his mouth and bit into his sandwich with his eyes closed. His teeth tore the bread and the meat, and he chewed. I followed suit. We were close for the moment, but time was conspiring against me.

I thought about it hard all that week. I reminded myself (I almost had to convince myself) that Brian and I both liked sports. And it was baseball season. So I asked my dad if we could get tickets to a game in Baltimore, and he said sure, of course. It was my last week of breathing. Next Monday was Memorial Day. Summer was almost here.

Brian and I arrived that final Saturday, signed in, got a number and a clear plastic tube from the box, and sat in our folding chairs. Brian opened his Sports Illustrated, and I opened my sports section and flipped to the box scores. The Orioles had beaten the Royals six to three. It was a good conversation opener. My heart thumped as I prepared to speak. But then the door marked Private opened, and Mrs. Boland emerged with her clipboard. “The good doctor,” Brian said under his breath. She called our numbers, and we took our plastic tubes to one of the four sections of plywood and breathed.

I was shut out from food, while Brian got a slice of a hoagie. “Lucky,” I said, repeating the line he’d once said to me. Then we breathed again. I didn’t get the mint, while Brian got one. “Lucky,” I said again. We had a half-hour left. Then the sub at the Hudson Deli. Then the wait for his mom on the curb.

“Orioles are finally starting to win,” I said.

“Finally,” he said.

I stuck to the script I’d practiced: “We should go to a game.”

“Us?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Do you want to, sometime? Go to an Orioles game?”

He set the magazine on his lap, face down, and gave me a sideways glance. He closed his lips, then relaxed them and said, “I don’t think so.”

Brian picked up his magazine and resumed reading. What do you say to an answer like that? My time was up. A partition had been erected between us, invisible but as real as the plywood that separated those who breathed from those who sniffed. I buried myself in the box scores and tried to pretend it didn’t matter.

At 10:30 Mrs. Boland called our numbers for the final time. I took my tube to one of the four sections of plywood. Through the hole I could see the man’s nose, his mouth, the clipboard on his lap. I bent down with the tube pressed to my lips, but then I took it away and put my eye to the hole instead. The man was probably in his fifties, with a lined face and thick, horn-rimmed glasses. His eyes were blue. He looked like someone who would teach mathematics in middle school. I stared into his eyes, and he stared into my one, but only for a moment. Then I inserted the tube into the hole. And I breathed.

Years later, when I finally acted on my desires, I went to the river and the woods that skirted it. I didn’t know what else to do. I went at night, just after dusk. I found the trail, and I stepped into the woods. I saw trees and rocks and roots. I heard rustling sounds around me. A hand landed on my shoulder and pulled me behind a bush. Lips pressed against mine. A tongue. I tasted tobacco. I smelled aftershave. There was little to see — only shadows and the glint of jewelry.

On the curb outside, Brian tore into his sandwich and chewed, a dab of mayonnaise at the corner of his mouth. I hadn’t eaten anything — no hoagie slice, no mint. I should have been hungry, but I wasn’t. I kept my half sandwich in the paper bag, clutched it along with the newspaper I’d read and read again. We waited on the curb for his mom. Brian ate his sub and breathed through his nose. I sat next to him, careful to keep my breathing even.