I find that most people know what a story is until they sit down to write one.

— Flannery O’Connor

At two o’clock in the afternoon on March 18, 1998, while typing up a story on a snowy gray day in Room 8 of the Sunset Motel in Hays, Kansas, I heard the crackle of tires in fresh snow out front. I had recently quit the radio-antenna factory, having saved enough to write for three months before I would have to go back. Though I was forty-two and had given up woman, dog, and comfy job for this writing “career,” my life was not taking any significant shape. If I’d been earmarked for success, I believed, it should’ve happened long ago.

Then someone knocked on my door. It was the FedEx man, standing in the snow. I didn’t know who would be sending me anything FedEx. I signed for the package, thanked him, and closed the door. The letter inside the cardboard envelope read: “It is my pleasure to inform you that Garrison Keillor, guest editor of the 1998 edition of the Best American Short Stories, and I have chosen your story ‘The Blue Devils of Blue River Avenue,’ originally published in The Sun, for inclusion in this year’s volume.”

I thought it must be a joke, though I knew no one who could fabricate such a convincing letter. I had never much liked these Best American Short Stories (BASS), but now, as I reflected on them, I decided they were pretty good after all. I realized this was a huge boost to my “career.” I wondered why they had picked this particular story. It hadn’t been nominated for anything. I’d never gotten one fan letter about it. But I figured that much of what happens in the literary world is a lottery, and I had been plugging away for a while, so maybe it was time for my head to bob to the surface of the sea of drowning writers, if only for a few minutes.

I went next door and showed the letter to my neighbor Chick, who was striving to be a painter and was probably the only one in this residential motel — perhaps in all my circle of working-class acquaintances — who could appreciate what had happened. Chick didn’t know what BASS was, but he recognized the name of Garrison Keillor, and he let out a crow. Chick liked Guinness, so I bought a sixer, and we raised a few creamy black drafts to the snowy gray sky in honor of the lottery that consistently rewards artists who do not deserve to win, but that keeps all us writers, musicians, and painters going by filling us with hope. A reward for mere persistence is not such a bad idea.

My parents were thrilled when they heard the news. They had been patiently putting up with my infinitely slow growth, perpetual pennilessness, and occasional collapses for years. Now they had something to tell the neighbors and relatives, who secretly thought I was a bum — and would secretly continue to do so, since they had never heard of BASS, and I wasn’t rich yet or on television.

The BASS publication paid five hundred dollars — which meant five more weeks away from the factory — plus an additional hundred if my story was deemed fit for an audiotape narrated by Mr. Keillor himself. It was! Imagine that: six hundred dollars for a story that took me only six years to write. If you’re dreaming of the big bucks, fiction writing is definitely the field for you, though you might also consider milk delivery, door-to-door encyclopedia sales, or shoeing cart oxen.

I walked around in the clouds for a whole day, telling anyone who would listen about my good luck. But then it was time to get back to work. I’d had my little fling with fortune, and if I wanted another, I’d have to sit down and write for ten more years: buy as many lottery tickets as possible. More important, I hoped to earn enough for one or two more weeks away from the factory.

But then something even stranger happened: The hallowed American publishing house Burns & Sons (not its real name) asked to see my work. Was I under contract, they wanted to know. Did I have an agent? Did I have a novel they could look at? A collection of stories? I told them my dozen novels in progress were all in various states of disrepair, but I had many published stories. They said please send the stories. They couldn’t be serious. I had been knocking myself out for ten years and couldn’t even get an agent, and now one of the largest publishers in the world was blithely asking me to send them a bunch of stories. I thought of stories only as exercises for the novel I would complete one day. No one reads stories. Name me the last collection of short stories that made the bestseller list. Stop a hundred people on the street and see if one can give you the name of a contemporary short-story writer besides Stephen King.

Things got even weirder when B&S decided they would publish my collection. I signed a five-year contract for five thousand dollars up front and five thousand upon delivery of the manuscript. And since the manuscript was already complete (or so I thought), I was suddenly two years away from having to return to manual labor. My future rolled out to the horizon with red carpets, smoking jackets, and trumpet music: the story collection would sell respectably; B&S would take all twelve of my novels (after I’d spun them into dazzling form); I would tour the country, appear on Oprah, and mumble at various university podiums for ten thousand a pop about character development and the need for world peace.

I was assigned to an editor. I liked her at first. We’ll call her “Deb.” She seemed competent and energetic. She seemed to have a good sense of humor. She seemed overworked. She thought my stories were “terrific.” Even if she was young (she imagined that children in 1965 might spend a rainy day inside playing video games), she had been hired by one of the savviest, burliest, most profitable publishing outfits on the planet, so she had to be good. I didn’t know where she’d come from or whom she had edited before, but should a beggar demand to see the chef? I was too grateful to be out of the rain while my old battalion, the 107th Dreamer Division, huddled in their soggy coats and pressed their noses longingly against the glass.

I was pretty old for my first book — according to our publishing schedule, I would be almost forty-four by the time it appeared — and I knew that B&S had signed me as a longshot prospect. Getting me under contract was like optioning movie rights: a freeze on the competition in case I did something interesting (or profitable). My first book would have a limited print run and would be a paperback. No big promotional campaign was in the works. I understood that this might be only a peep through a crack at the big time. I was like a character in a movie called They Were Expendable, and the film editor was studying my hazy frames with a pair of scissors in his hand.

Still I was stubborn. No way would I go back to the minors and hit pop fouls in front of those small crowds again. I’d had day jobs for twenty-five years now. I’d paid my dues. So when Deb sent me the B&S style manual, A Guide for Authors, and a personal three-page letter on how to write (“I know this is a lot to absorb”), I took it in stride. Certainly I had room to grow. I was no Thomas Wolfe. I didn’t even have a college degree. Anyway Deb gave me the impression that out of the fifteen stories I’d sent her, all of them previously published in magazines and journals, we were just about there.

But Deb did not like travel stories, or drinking stories, or stories that read like nonfiction. She didn’t think it credible that my characters quit jobs without giving notice (the way I did), that many were obsessed with suicide (the way I was), that romance was a guaranteed bust (me again). She liked childhood stories, like the BASS winner. This cut the number of potential candidates from fifteen to four and made me sound like that guy who wrote Mr. Popper’s Penguins. But who was I to argue? I was free from the factory. I had almost seven grand in the bank and a book coming out and unlimited potential. You take a little, you give a little. There is no success without compromise. I had a bundle of experience to draw on for material. Certainly I would be able to come up with a few more stories.

Deb and I talked on the phone at first, collect calls I made from the Hays Public Library. I felt as if I were talking with someone whose feet had never touched the ground, who had worked part time at McDonald’s for one summer before obtaining her MFA from an ivy-walled university and then had immediately moved into plush chambers littered with Diet Coke cans in a tall building where people on their coffee breaks glowed about John Updike’s latest. I mumbled and hawed. She was cordial, complimentary, and encouraging. I discovered that she was assigned to “new and young” writers, of which I was neither. A little fold rose in the landscape between us and took the shape of a mountain. Eventually we returned to the remote safety of our personal computers.

As the stories went back and forth from Kansas to New York, a pattern emerged: she didn’t generally like my endings; the beginnings were not much better; and frequently the middles were not right either. She was obsessed with “character motivation” and “setting scenes,” and thought that the secret to success was “draft after draft.” I believed in rewriting too, though I’d learned that if you didn’t have anything in the first place, if your characters were not alive, if the purpose of the story was not clear (especially to the person — or people — writing it), if you kept turning left down dark alleys instead of right toward lighted avenues, then no amount of rewriting would alter the fact that you were just finger-painting in a heap of llama droppings.

Deb, however, new and young herself and eager to show her superiors that she could whip this droll drifter into shape, was tireless. Draft after draft we wrote, like an arranged-marriage couple on a forced honeymoon, or two sailors varnishing stove-in boats washed up along the Bay of Fundy. A perfectionist, she was tyrannically opposed to the word something. Neither would she permit the word spinster. My dialogue, without much exception, was “flat.” I used the word yellow too much. Free from manual labor and with nowhere to go, I began to write ten, sometimes twelve hours a day. My first book, unless I wanted it to die on the vine, had to be brilliant.

After six months or so of energetic heaving and arduous grinning and slapping about of lacquer brushes, Deb and I had come up with nothing — or, I should say, less than nothing, because the stories that had survived the first cut (even the BASS winner) had been changed to the point that I was having trouble recognizing them.

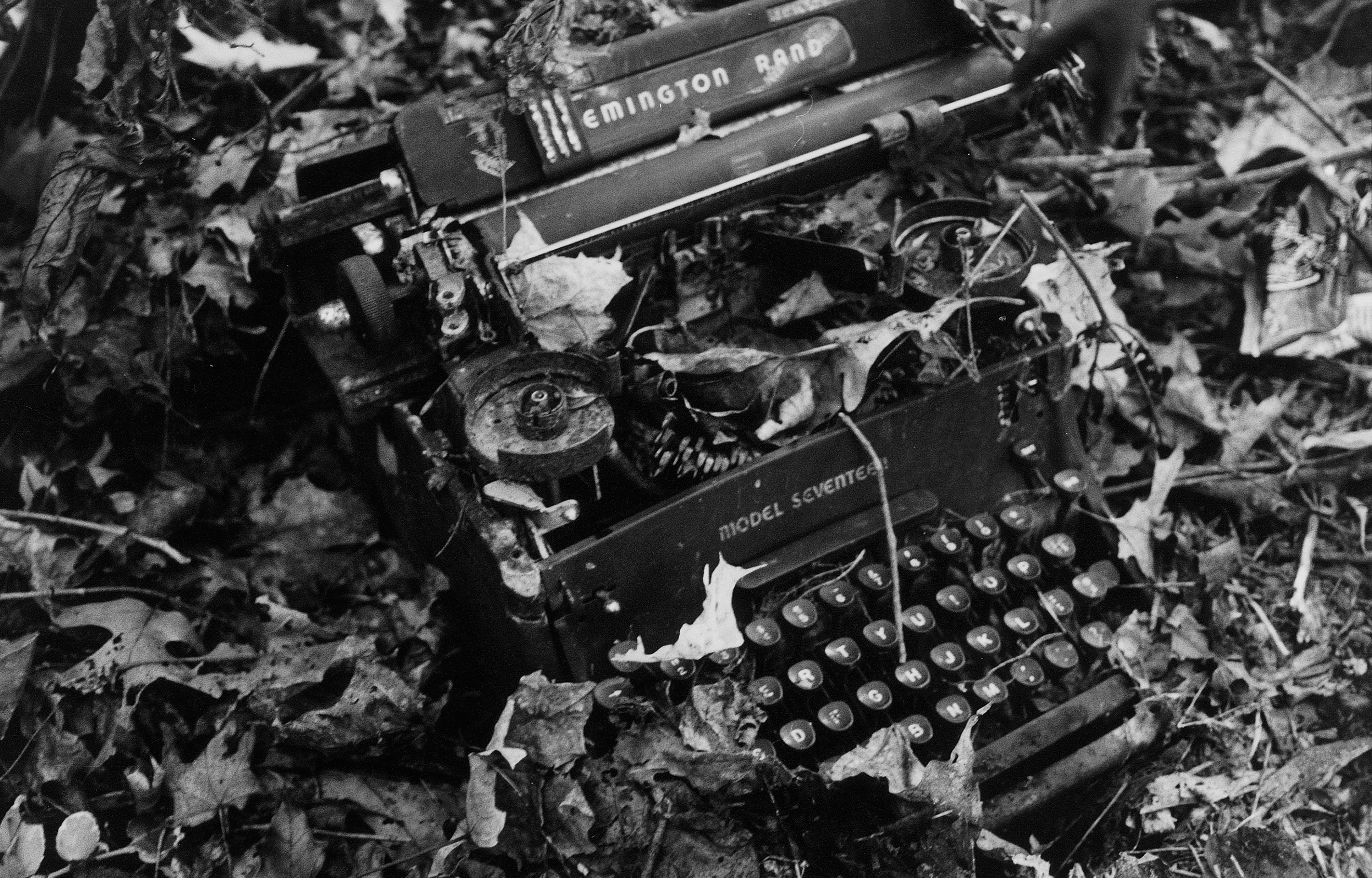

To give her credit, maddeningly ingenuous though she was, Deb was ever positive, especially about the new stories I’d write, since the old ones were in a shambles, like heaps of broken toasters with so many burnt crumbs among the twisted elements. But all the new stories went through the same hopper, and before long I lived in a fiendishly disheveled world of abandoned manuscripts, stacked in drifts like shifting sand dunes across my motel-room floor. My neighbor Chick, who came by once a week to hoist a few with me, was beginning to worry that I might be lost and my body never recovered.

When another story fell from the ranks, leaving three, I confided to Deb that I didn’t think I could do this anymore. I’d never written under pressure, I explained. I’d never willed a story to exist. Because I’m slow and haven’t found the philosopher’s stone yet, I have to write ten stories to get one good one. They come from the Land of Mystery on their own schedule. Often, like the BASS winner, they take years to develop, moving from novel to story to poem to essay and back again. And then, eventually, if I’m lucky, I have an accident: type the wrong word, or marry two disparate entities, or stumble across a solution in a newspaper article about a bipolar shoplifter in Mobile, Alabama. I’d like to write in a more organized, predictable way. I know in college they teach you that S(Story) = 1+2+3, but it isn’t true, not a real S anyway, not an S that doesn’t have an H right after it, followed by a quick IT.

It was not in Deb’s job description, her training, or her nature to be straightforward, and, to be fair, I think she really didn’t know what to do either. Who wants to be lowered down here in the darkness with just Mystery and me? But she was obliged to keep up my spirits. Even in my moments of darkest doubt, Deb never lost heart — though now and then she had to go to Rome on a two-week vacation.

I had never in my life felt creatively dead. I had never suffered from “writer’s block.” (I don’t believe in it any more than I believe in speaker’s block.) If you have something to say, then say it. If you have nothing to say, then you shouldn’t be writing, or speaking, in the first place. If you can’t write a novel, then writer’s block is going to save you a lot of time and trouble. Writer’s block is a blessing to us all; with eight hundred thousand new books published every year, there is obviously not enough of it to go around.

And neither was my problem “artistic integrity.” I was accustomed to aggressive editing. Talk with any writer who has dealt with The Sun, and you’ll hear a legendary tale of transformation. The editorial staff runs all submissions through giant paper shredders, turns the mounds over to caged marmosets on amphetamines, bellows Sufi war chants long into the moonlit night, and then begins the almost supernatural process of hand-dipping each shred of paper into Japanese squid ink before returning the manuscript, miraculously restored, to its sender. But I found this process relaxing compared to working with Deb, primarily because the editors of The Sun, though it might have taken a year to get a story to their specs, knew what they were doing. True, I was often puzzled and even disgruntled at the final version, but the point is we did produce; we did publish. I was paid, and the work was often improved, even salvaged. I received adoring letters, money, and photographs from admirers. Many of the stories were nominated for prizes; two won major prizes; several received honorable mention in anthologies. In other words, the relationship was beneficial.

So why, now that I had my chance to enter Blessed Meadows for Minor Poets, did Deb stand like an evil troll at the gates? I began to wonder if I’d sold out. Were the gods punishing me? Was it possible that I needed somehow to remain poor to keep my honor? Could Deb, who represented most of what I thought was wrong with the scholastic approach to writing, be some sort of divinely planted obstacle to test my faith? And if I passed the test (i.e., forfeited the contract), were even greater rewards waiting for me (easy, now) down the road? I had only one hard, fast rule at the time: If you get between me and the writing, out you go. But who would’ve dreamt that an editor at a giant publishing house, the wizard I had traveled so far to see, would be the one to get in the way?

As the stories were shipped back and forth, our cordiality cooled. My jokes to relieve the growing tension seemed inept and crude. I needed a break from Deb’s penciled changes and rewrites. I had ceased to produce anything, either with her or on my own. Day after day I stared into my amber screen and wondered what had happened to my voice, my instincts. I began to swear under my breath at Deb while I worked.

Perhaps a move to Mexico would provide the necessary change of pace. I had always wanted to live in Mexico, and now I had the money. Deb thought it was a good idea. We postponed publication of my story collection (hard to publish a collection with only three stories in it), and I headed south.

In Mexico I set aside the writing for a few weeks and melted into sun-dappled tranquillity. No matter what happened, for the next year or so I was a writer with a contract, and I could talk about my editor, my advance, and my forthcoming book, ad nauseam. Even if people didn’t like me (who would?), they had to grudgingly acknowledge that I had reached a peak where few had climbed before.

I liked Mexico so much I decided to renew my visa for six months, which required a return to the States. While in the U.S. I planned to ride around the country and see all my old friends before disappearing south of the border, maybe forever, as so many disreputable and forgettable writers before me had done. I also thought I might drop in on Deb in New York. Maybe we could get some things (not somethings) straightened out face to face where phone, e-mail, and the USPS had failed us. I wrote her, and she said it sounded good.

Off I went on a thirty-day bus trip around the U.S.A. Almost immediately I got sick. Then, in Colorado, my back went out. I limped and coughed from town to town, getting weaker and more bent out of shape. At each friend’s place I took to the guest bed, shivering and sleeping and trying to force down some chicken soup before I moved on to the next lucky household. I thought I’d shake the malady, but I couldn’t. After several thousand miserable miles, I barely had the energy to stand up from my bus seat and crack my head on the luggage rack. I thought about packing it in, but I didn’t want to give up the chance to see Deb and maybe set our varnished boats straight.

When I landed in New York City I should’ve gone straight to the emergency room. Instead I limped around until I found the great B&S Torture Research Center. I entered, went up in the elevator, and asked to see Deb. She was out, so I waited an hour in a small lobby. She was still out. Suspecting she was really there but unwilling to see me, I left, exhausted and crookedly bent, like a beggar selling matches. I thought about getting a hotel room so I could lie down, but there wasn’t one to be had for less than two hundred a night, and two hundred dollars would buy me more than three months in Mexico. So I crawled back to the Port Authority and called a friend, who wasn’t home. The guy next to me was taking his blood pressure — phwish, phwish, phwish — every ten minutes. I called B&S. Deb was still out. I called my friend: not home. Finally I climbed on the next bus, not even caring where it went.

Back in Mexico a month later, after I’d self-diagnosed from a Columbia University physician’s manual and made a trip to the farmacia to obtain the correct antibiotic to treat a general strep infection of a pneumococcal variety, I was well enough to resume the Sisyphean labor with Deb. But first my embattled instincts advised me to work independently of my esteemed editor, and with facile speed I produced two pieces that sold immediately. The contributor’s notes that accompanied them looked very smart: short-story collection forthcoming; BASS award winner. Deb loved the pieces (they were “terrific”) but thought they could use some changes. I decided to leave the stories the way they were.

The only story Deb and I ever collaborated on that worked was one I’d had lying around for about eight years about a childhood dream connected to fear of old age and death. Deb had some strong ideas, as usual, about how the story should be different, and I rewrote it to her specifications. I think after about the fifth serious rewrite she decided she liked it — except that the opening was too much like that of the BASS winner, the dream (which was a real one and the reason I’d written the story) was trite, and the ending was not right. Oh, and some of the parts in between she thought could be cut or reworked. In other words, a three-thousand-word story that I had been working on with her for five or six months was OK except for the beginning, the middle, and the end.

Tired of walking in circles, I stripped the story back as best as I could to its original form and sold it to Atlantic Online. Several readers wrote to tell me how weak this story seemed compared to my usual, and how it wasn’t plausible in spots. They were right. Together, as in all the stories, Deb and I had implanted plot devices that didn’t fit, added irrelevant romantic scenes, brewed hokey moral themes, applied ourselves to trivial color schemes, constructed useless motivational apparatuses, and ridden the donkey the rest of the way into town only to learn that the villagers had moved on long ago.

I was on my third Mexican visa, and my savings were almost gone. I needed the second half of that royalty advance, but I wasn’t any closer to finishing the book than I had been on the first day. What little material I had was so humpbacked and weird and unlike anything I would ever compose, even in a fever or after being struck in the back of the head with a pool cue, that it made me ill to think of it. Another postponement of publication was waiting in the wings. I loathed the idea of going back to the U.S. to get a kitchen or warehouse job. I would’ve worked in Mexico if there had been decent (legal) jobs to be found — anything, say, that paid more than the going rate of seventy cents an hour.

One morning I was taking coffee with my American expatriate friends at the Hotel Jardin when a young man stuck his head in the door and asked if any of us would be interested in teaching English. The other Americans, all retired, engaged him in polite but disinterested conversation. The young man said his wife owned a nearby language school, and the students were demanding at least one native English speaker on staff. Polite and wry declinations followed all around. Then my turn came.

One reason I had come to Mexico was to learn Spanish. Like most Americans in a foreign country, however, I had clung pretty tight to my own ethnic island. And though I studied nightly Margarita Madrigal’s Magic Key to Spanish, which begins with the past tense, I was making unremarkable progress. Whenever I walked into a store and tried to have a casual conversation in Spanish with an employee, I was greeted with a horrified look, signaled to wait, and, after a few moments of hasty scuffling, presented with some poor soul who spoke English. Children who came to my door to ask if I wanted my trash taken out seemed to think I was particularly funny when I attempted to engage them in any dialogue beyond “Sí” or “No, gracias.” Teaching English paid only a whopping two dollars an hour, but it would allow me to interact with Spanish-speakers and get me out of my giant, empty house, where I was surrounded by piles of manuscripts scribbled upon by a well-meaning but wicked lunatic, and where time passed more slowly than all of my Sunday-school classes put together. I took the job.

Teaching English turned out to be the best way to learn Spanish. Growing up in San Diego, I’d taken Spanish in school, worked in plenty of kitchens with Mexicans, and spoken some kind of ragtag Español most of my life. But in nontouristy, agricultural Mexico, six hundred miles from the U.S. border, you need more than thirty-two words and seven pet phrases, chief among them “Cómo se dice . . . ?” (“How do you say . . . ?”) To teach English I had to learn Spanish grammar and all the elemental vocabulary that I’d glazed over before: through, about, unless, around. Hour after hour I had to explain, in Spanish, why a pronoun inserted itself here but not there, and why the verb tense did not change with an auxiliary. If the pupil (or the teacher) didn’t understand something, we repeated the lesson until it was clear.

Before I realized it, I was among the natives: sitting on a park bench, standing in a doorway smoking a cigarette, eating tamales at a restaurant. I was making lame jokes, asking ridiculous — but syntactically correct — questions, or fending off someone trying to sell me a “genuine Rolex.” I was invited to dinner, to chess, and to bed. I learned where to buy the best mangoes, chicharrones, and menudo. Cheaper rental opportunities opened up. If I needed something fixed, a special deal, a prescription perhaps, these doors opened as well. I met my students after hours to help them pass their tests. I began to date one of my students. (This part of me I’d honestly thought was dead.)

Meanwhile, back at the bloody grindstone, Deb and I worked on my stories until they wore out or fell to pieces. I’d been confidently sending out these mutually composed pieces with cover letters that read, “I have worked with my editor from B&S (short-story collection forthcoming) on this one, and I’m pretty sure it can’t be topped.” The story usually came back without a comment. Even The Sun, my old standby, showed little interest in these coauthored compositions.

Since I had been selling stories for years without Deb’s help, and since every labor between us had fallen through the grate, I was finally forced to conclude that Deb — a manic perfectionist who didn’t know what she was doing, or why she was doing it — was not in my best interests. The little voice in my head that always knew when it was time to go said, Time to go.

But, like a starving dog with its head stuck in a garbage pail, I couldn’t give up the B&S contract, and Deb knew it. At my wits’ end, I sought counsel from a few trusted friends.

Fire her, they said.

Fire her?

Yeah, get a new editor. Everyone does that.

It sounded like the smart move to make: if you’re standing next to a bubbling pot of sulfur, and some demon with red eyes is handing you a quill dipped in blood, you ain’t in heaven. But I gave it a couple more months, just in case Deb fell off a mountain, plugged her curling iron in backward, or married a revivalist preacher. Meanwhile my meager savings continued to dwindle, and if I wanted to stay in Mexico, the second part of that contract money was the only thing rescuing me from the factory. But it had gotten to the point where the drone and grit and smash of the factory would’ve been exhilarating compared to staring at those packages with the penciled outlines and the little, carefully scribed, Beelzebubian comments in the corners.

Finally in June I wrote to Deb and said that we were incompatible, that nothing we had written together had worked. I cast myself as the temperamental artist, though I didn’t feel much like an artist, having written nothing of worth in two years. I tried to be nice. I was courteous, which is a mistake in the business world. (In business one must lay the blame elsewhere, be the aggressor, raise some hell and demand to see the manager.) I told her I wanted a new editor or out of the contract.

I think Deb, not wanting to share responsibility for our failure to produce, simply told her supervisor that I had pulled the plug. And I had been expendable from the beginning. They released me from the contract and waived the five-thousand-dollar advance, unless another publisher picked up the collection, in which case I would have to refund the money. Deb and I wished each other luck and never spoke again.

Mumbling regret, cursing myself, and rolling my eyes heavenward every four minutes, I went back to the States and got a job in a pallet factory, then a sheet-metal factory, then a cheese factory. The big-publishing-house experience had been so unpleasant that I vowed never to do it again — though it’s true that, without the advance, I never would have made it to Mexico, never would have learned to speak functional Spanish, never would have found that mango, that menudo, or that mariachi band, and probably never would have had another date. (You can’t imagine how much that was like a resurrection.) Eventually I found another publisher: a small press this time, no three-page letters on how to write or yellow-phobia. No short-story collection either. I suspect there’ll never be one. I still can’t afford to pay back that advance.