We are bouncing over a rough ocean, on a boat packed with twenty or so fishermen, and I am breathing the smoke from my grandfather’s cigarettes. In the darkness of early morning the captain collects money for a gambling pool. “First and heaviest, thirty-seventy split,” he yells, and when he gets to us, my grandfather hands over a fistful of bills. As the captain moves on, my grandfather winks at me and says, “You will win.”

When we finally let our baited hooks fall into the sea, I magically get the first strike of the day and pull up a fish that hardly weighs five pounds.

One fisherman says, “That’s only the bait. The kid’s claiming that his bait is his catch.”

Other men who have money in the pool protest too. I am afraid that the captain will not count my fish, which is alive and certainly not the piece of raw flesh that my grandfather slipped onto the hook for me earlier. But the captain pats me on the head and sticks a wad of bills into my hand. My grandfather looks on proudly.

I am so excited that I begin puking over the side of the boat.

I try hard not to cry, but my eyes are burning, and I can’t help it. My grandfather lays me down in the middle of the boat, and the men cover me with extra jackets until I can no longer smell the bloody bait or the cigarette smoke or the fumes from the engine. Somehow I fall asleep.

When I wake up, my grandfather is carrying me to his car. “Check your pocket,” he says, and when I do, there is so much money. “You got the only fish of the day,” he tells me. “You won the entire pool.” With my cheek against his chest, I smell the odor of gas and sweat and fish and cigarette smoke that I will forever associate with my grandfather.

“Just like you promised,” I say to him.

He laughs, and all my life I will wonder if I really caught the only fish, or if my grandfather stuffed my pockets with his own winnings.

After I became a man, a paid professional put a staple through the cartilage of my grandfather’s ear and made him listen to hypnosis tapes that taught him to associate the constant pain of the staple with cigarette smoking. A week later, in a fit of agony, my grandfather pulled out the staple. He kept the tiny but awful strip of metal — crusted over with his blood and hardened pieces of skin — in a small box, which he carried around in his breast pocket in lieu of cigarettes.

He was finally able to quit smoking, but not before being diagnosed with emphysema.

My ailing grandfather missed my wedding and lived out his last months tethered to an oxygen tank, barely able to walk from one room to the next. At the end he lay in a hospital bed attached to a horrid, hissing machine that pumped pure oxygen into his lungs. The last time I saw him alive he was unconscious, an emaciated stranger in a hospital gown with tubes running into his arms. I held his hand and heard my aunt whisper to my mother that I was taking his death “awfully hard.” Awfully hard? I thought, but said nothing. The hospital smell had already pronounced my grandfather dead. He was an auto mechanic who’d never smelled antiseptic in his life. I let go of his hand and left the hospital. I wasn’t there when they pulled the plug.

During my grandfather’s long, drawn-out death, I smoked one cigarette a day. I was neither addicted to tobacco nor trying to quit. Every evening, on the second-story balcony of my apartment, I would have a cigarette and watch my stained breath slip away into the night sky like a prayer.

I had my first cigarette when I was in the sixth grade. There was a girl in my class whose mother let us smoke in her apartment, and even provided any brand we desired, free of charge. (This girl was very popular.) The first drag made me want to vomit, but I took another and another until, amazingly, I liked smoking. It felt right somehow, like breathing. Not cool or hip, but right.

Organized sports kept me smoke-free in high school, but I started smoking regularly when I was in college. I was an English major, and many of the authors I admired smoked. The professors who would have a cigarette with me between classes were always the best professors. To me back then, smoking was a great barometer of character.

I was — and, I guess, still am — the type of smoker who will never become addicted. I can smoke a pack a day and then refrain from smoking for months. I once watched a television sitcom in which a character says basically what I just wrote, and an addicted smoker retorts, “There’s a word for smokers like you: bitch.” And, indeed, I felt like a bitch when one of my best friends — to whom I had given many cigarettes — got addicted and had to wear an expensive nicotine patch to quit. And I feel like a bitch knowing that another friend’s little brother, who used to steal cigarettes from my glove compartment when he was in high school, still smokes my old brand.

My mother asked me once how I could ever smoke after having seen what cigarettes had done to my grandfather. There is no good answer to this question. Maybe I should have said that I did not value my life enough to care, that sometimes it seemed as though whatever comes after death might be a welcome alternative — so why not speed up the process? (As a Christian who believes in a literal heaven, she should have understood this concept.) Or I could have argued mathematics, saying that my grandfather had smoked as many as forty cigarettes a day for half a century, whereas I smoked only one cigarette before bed each night and maybe a few more at the bar on weekends — therefore I was unlikely to meet the same unfortunate end. I think if I’d told her I was addicted, my mother would have better understood my need to smoke, but I was not addicted. So I simply shrugged and said nothing.

I no longer smoke, except when I am in a foreign country. I have made a deal with my wife that, when abroad, I am allowed to smoke the local brands with the local people, as a cultural experience. This is silly, I realize, but it sounds refined to say that I am an “international smoker.” Rest assured, I am not out of the country enough for this to seriously affect my health.

OK, sometimes I do smoke clove cigarettes with a friend, but we don’t inhale, so it doesn’t really count. We smoke them because the ends are laced with sugar, and the smell of burning cloves is enchanting. When we are hanging out with our partners, my friend or I will say that we need some “man time,” and we will leave the women and go smoke clove cigarettes under the stars. We puff, sip whiskey, nod a lot, and generally enjoy this time together. Somehow the ritual eases the strain of everyday life and makes us feel closer.

Once in a while, my wife will puff on a cigar with me, which is sexy and fun.

If I see people smoking in a movie, I want to smoke. If I am at a bar with a smoker, I want to smoke. If I read about smoking, I want to smoke. But smoking has become socially unacceptable, so I rarely smoke a cigarette anymore.

My nieces and nephews have been taught that smoking is evil, and they will point out smokers in public and tell me that these are bad people. I say nothing when they ask, “Right?”

One night a few years ago, while my wife and I were backpacking through southern Africa (where it is still socially acceptable to smoke just about anywhere), I got drunk and walked out onto a pier to smoke a cigarette with another backpacker, a hilarious Iranian-born Englishman whom I had met the week before. I looked out across the moonlit Atlantic and felt the salt mist on my face and sucked the cigarette smoke into my lungs and blew the gray clouds out through my lips, and suddenly I began to think about my grandfather. It must have been the smell of smoke and the gasoline fumes wafting from boats docked nearby. The feeling was so intense that I wanted to cry. Far from home, an entire ocean separating me from everything and everyone I knew, I thought of my grandfather as a young man in the navy, navigating the same black ocean I was now gazing across, and of the smoke that issued from his lungs and climbed toward the same stars now overhead. I lit another cigarette, and when my wife reproached me, saying that I was smoking too much, I loudly proclaimed that the cigarette in my hand would be smoked for my deceased grandfather and that I wanted to be left the fuck alone. Annoyed, she and the Englishman walked away while I stood at the end of the pier and watched my breath escape my body. Smoking with my back toward the others, I wept quietly for my grandfather.

My wife is a yoga teacher, and in her class I have learned the three-part yogic breath: draw in three breaths on top of one another, gradually filling the lungs bottom to top; then exhale the entire lungful slowly and deliberately. This process is repeated until the breather is in a trancelike state. My wife has also taught me how to slightly constrict the back of my throat and breathe in and out through my nose, making the sound of the sea. When I breathe using these techniques — and notice that I am breathing, and appreciate that miracle — I have visions. Images from my past will flicker across my mind’s eye: me fishing with my grandfather; or helping pump gas at his station; or digging for the coins that he hid in the sandbox. And I see the future too. It dances upward from somewhere deep within and then dissipates before I can remember what I’ve seen. My wife has taught me how to sit and experience the calm, quiet edge of a universe I cannot even begin to comprehend. The practice is intimidating, but also pleasing and cathartic.

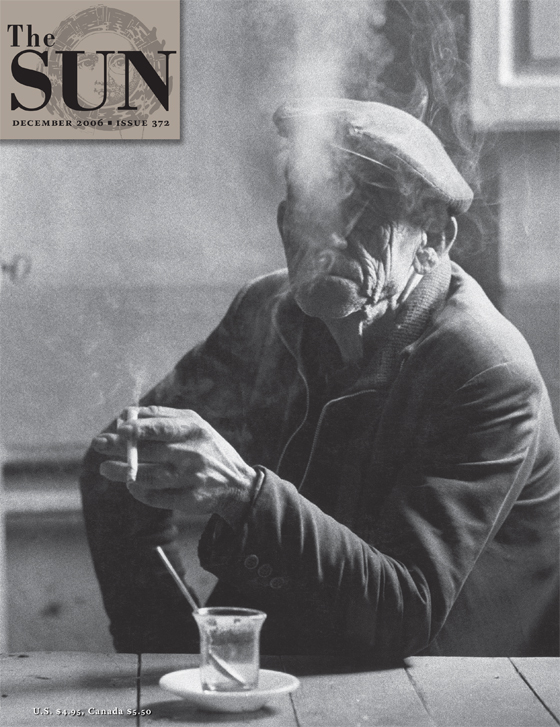

No one ever taught my grandfather yogic breathing exercises, but he still used his breath to break up the endless routine of his days: he lit it on fire and watched it exit his body and float upward. Smoking was a bad habit, fueled by a chemical addiction, and it ultimately claimed his life. But I like to believe that he thought about something of consequence when he was alone, watching the orange cherry burn at the end of a butt. Perhaps he too wondered why he was there to smoke or think at all. I never rue the fact that my grandfather was a smoker. I just wish he had told me what it was he saw when he was alone with his thoughts and his cigarettes and his painful memories and his hopes and his need to light up. What was it that he learned through the years of smoke? Was he afraid at the end of his life? And were those few extra months spent attached to an oxygen tank worth the agony of quitting, the hypnosis tapes, the staple in his ear?

Whenever I smell cigarette smoke now, I think first about my grandfather, then about how many inhalations I have left, and I slow my breath and breathe in deliberately and savor the filling of my lungs. And then, when I cannot possibly take in any more air, I exhale slowly, slowly, slowly.