The cord on the phone is cut straight and neat. There are two small nicks higher up on the cord, where he tried the knife but it didn’t cut through.

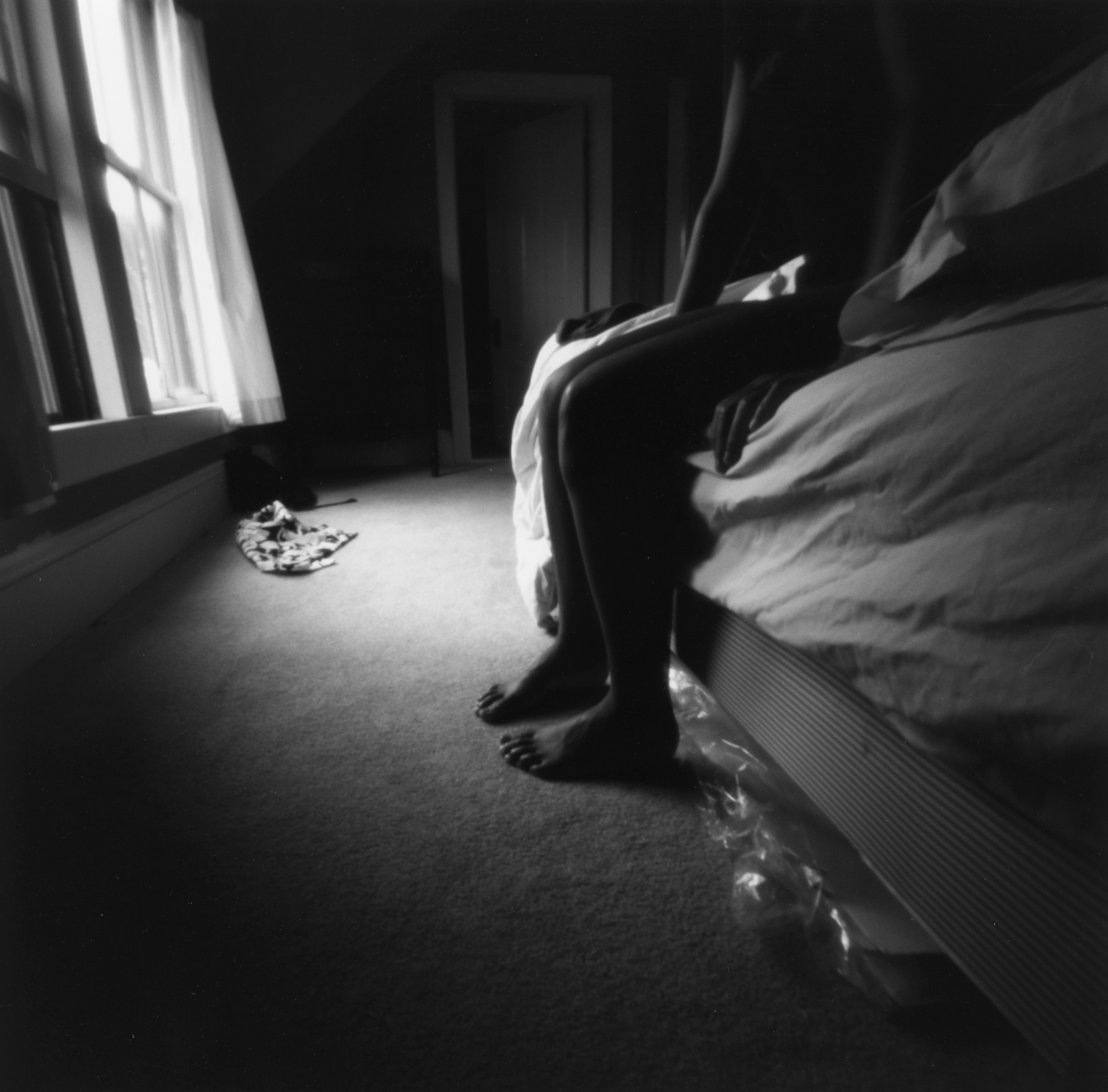

You call your mother from a neighbor’s apartment. You don’t know the neighbor. She saw the police cars and the uniforms and the detectives coming in and out of your apartment this morning. She saw you taken away in the shorts and T-shirt that you had put on. She saw you dropped back off in the blue hospital scrubs they gave you after they’d put the shorts and T-shirt in a plastic bag as evidence.

You don’t tell the neighbor what happened. You want to. You’re in the habit of telling strangers by now. It happened less than eight hours ago, and you’ve already told five. The policeman in uniform was first. Then the doctor at the hospital. There was a nurse there too and someone from the police department to look for fingerprints on your skin, pluck your dark hair, comb for hairs that weren’t yours, scrape under your nails, take pictures with a Polaroid. You were a crime scene. And then there was the detective at the police station. She wore a brown suit and sat at a gray metal desk that she shared with another detective, who brought you coffee.

At the neighbor’s apartment you sit on a plaid ottoman by the end table where she keeps her phone. She has stepped outside for a cigarette but left the door open. She leans against the wall with one foot up and her head tipped back to let the smoke flow from her lungs up to the sky.

The sky is blue. It’s warm in the sun and cool in the shade. It could be a perfect spring day, the kind of day to take your books and your mesh lawn chair out front and set yourself up by the sidewalk in a slice of sun. It could be the kind of day where you mean to study but instead just stretch your legs out and relax. If you weren’t here now, using her phone to call your mother, you might have met your neighbor out there in that slice of sun.

You call the number for the farm where you grew up and where you lived until last summer. It’s been the same number all your life. You know it will be your mother who answers and not your father, because he never answers, especially when your mother’s home, and she’ll be home on a Sunday afternoon. You always call on a Sunday.

The smoke from the neighbor’s cigarette drifts in, and you want one. You set the receiver in your lap and rest your elbows on your thighs and your hands on your knees. The receiver is lying in the triangle made by your stomach and your arms. The dial tone is weak. You practice the words without saying them: A man broke in, I was raped, a man broke in, I was raped, a man broke in, I was raped.

Your mother answers from the only phone in the old farmhouse, next to the big picture window. Outside the window are the fields and the barn and the picket fence and the front walk and the porch.

You say, “Mom?” as a question, the same way you always do. Before she can answer, you say, “It’s me,” the same way you always do. She doesn’t know yet that anything is different than any other Sunday afternoon.

She says, “Oh, hi, honey,” like it’s a surprise to hear from you, like she wasn’t expecting you to call. She doesn’t expect anything from you, except that you be in college. “You have to go,” she told you in your last year of high school. You were at the kitchen table, and she was standing beside you, mixing cake batter. She held the bowl between her arm and her side and used a wooden spoon to beat the batter, counting. “You’ve got the smarts,” she said and picked up her count four beats past where she’d left off.

Now your mother is by the picture window. Maybe the swallows have been darting in and out of the porch. They come back every year to build their mud nests where the roof meets the house. Maybe this year she won’t fight them. Maybe she won’t put up strips of plastic to deter them or use a broom to knock away what they’ve started. Maybe this year she’ll leave them be.

You say, “Something happened.” You wait and think you hear her sigh or the sound of the swallows. You say, “A man broke in,” and your mother takes in a breath, big and sudden.

“Oh, no,” she says.

She doesn’t know the rest: His nylon mask. That knife. The dark shape of him over you. You can’t tell her any of those things. All you can say is “I was raped.”

The neighbor is still smoking her cigarette. It takes just a minute for you to tell your mother, even though what happened took hours.

“This is going to kill your father,” she says. Because she was a virgin when they married. Because your mother remembers your father once told her that he didn’t think he could stay married to her if she had been with another man, even if it had been rape. But you are hardly a virgin, and you hope your father knows that.

You tell your mother not to come. You’re an adult now, and she respects your decision. That’s how your family is. They don’t cradle or coddle or come running. When one of you falls, you stand up, and you carry on. You are her fourth child, the only one who’s moved this far away, and even though she always said she raised you kids to be independent, she worries about you: the college you chose, the ways in which you’ve shut her out.

“I’m OK,” you say. Because you want to be. And you stand up, move the receiver away from your ear, and lean over the phone. “There’s nothing to do,” you say. “I’ll call you next Sunday.”

You hang up the phone, which brings the neighbor back inside. She’s blond, taller than you, and older by just a few years. Your front doors face each other. You don’t even know her name. You wonder why he picked you and not her.

“Thank you,” you say. You look at the phone in its cradle and think of your mother far away.

“Is there anything else you need?” the neighbor asks. You know she heard you talking to your mother, because she was close enough to the door, and the day is Sunday quiet. Now she picks up her purse and keys. “I have to go to work. But when I come back . . .”

You imagine she’ll go to work and tell everyone that something happened to the girl next door, that there were cops, and the girl used her phone, and she’s pretty sure the girl was raped. And she’ll say how, if a man tried to rape her, she would fight. (She doesn’t know about being afraid.) She would hurt that motherfucker, knee him in the nuts, even if it was very early on a Sunday morning — still night, really — and she’d been up late and was finally asleep, deep and safe, and it was the last thing, the very last thing, she ever expected.

It’s in the paper the next day: a twenty-year-old woman was raped early Sunday morning. Your name is nowhere in the article. You have become a secret.

You’ve read that in some parts of the world men will kill a woman in their family who’s been raped. Farmers in small villages kill their daughters; brothers kill their sisters. If she’s had sex outside of marriage, she’s dishonored the family. It doesn’t matter if she didn’t say yes. It doesn’t matter if it was in the dawn of a fine spring morning and she was still half asleep and a man she didn’t know was suddenly over her bed with a knife from her kitchen and a stocking over his head. It doesn’t matter if he pressed that knife into her side, not cutting, just saying in a fast, hard whisper, “Shut up shut the fuck up if you don’t do what I say I’ll kill you.” And she did what he said in the gray light that came in the window from the alley behind her apartment.

You are not ashamed. You are stunned: By this new thing that he left behind, that spread through you like blood in those hours he was with you. By how easy it is to die.

Your father doesn’t call for a week.

During that week, you replace the phone cord. You make plans to move to a different apartment. You clean your place every day. You continue to find fingerprint dust on baseboards and the insides of cupboard doors.

During that week, the detective comes by in her brown suit. She says, “I thought I’d check in with you. See how you’re doing.” She sits on your couch, and you sit in the chair next to it. She hopes you’ve remembered something new that will help them find him. You haven’t. “We don’t know who he is,” she says, “but you’re part of a pattern.” She buttons her jacket and says, “The way you look, how long he stayed.” She runs her thumb in a circle on one of the buttons. “What he said to you.”

She typed those words into her report: Where’s your money? Fucking bitch. I’m going to fuck you. Touch yourself. I’ll kill you. It was her day off, but she’d come in anyway that morning. Gone to the hospital with you to try this new method, fingerprinting your body. He’d been due to strike again, she says, so she wasn’t surprised. That’s how she finally knew she was a cop: that she was ready for the next one. Typing those words probably didn’t make her flinch or think what it would be like to have a man lay himself on you, a man you don’t want, and tell you to touch yourself, put you on your knees and tell you to suck it, eat the food from your refrigerator and cupboards, tear your towels, tie you up, take that knife again and touch the tip to your back while you lie facedown on the carpet and every bit of your body shakes, maybe from cold but mostly because you don’t want to die, and you try to make it stop, but it won’t.

“We think he watches his victims first,” the detective says. She sees the way you’ve shut down just to get on with living, and she asks, “Have you talked to anyone?” And you say no; you don’t mention the boy you dated for a while and ran into yesterday outside the bookstore, how his face got tight when you told him, and so you moved on to something else, another topic. And you haven’t talked to your mother again, because you told her not to call, and not to your father, because he hasn’t called.

The detective hands you a card with a counselor’s name. “You should call this woman. She works with rape victims.”

Exactly what you don’t want to be.

After the detective leaves, you throw the card into the trash. You are in college to become a counselor, but even though it is what you are studying, you don’t think talking to her would help. The next time you put something in the trash, there’s the black-and-white card: “Rape crisis. Victims’ assistance.” You empty your ashtray on top of it.

During the week that your father doesn’t call, you go to your classes, because that’s why you’re here in the city: to go to college and get your degree, because you’ve got the smarts and you won’t waste them. You go to the office of a professor you really like and ask for an extension on a paper that’s due. You tell her why. She’s late for a class and packing her briefcase. She doesn’t have time to sit and talk. She doesn’t know that she is the one you hoped would tell you what to do, if there is something to do.

It’s in another class, with a professor you don’t really like, that you start shaking all over. It’s the sitting still, listening to a lecture that suddenly seems too hard to understand, being around all these other students, these people who don’t know. You get up fast and leave the room, and the professor follows. She calls your name. You’re surprised she knows your name. You tell her what happened, cry for the first time. And she tells you that she was raped too. A long time ago. That it will get better. She tells you to go home now, come back when you’re ready, come talk to her anytime. She hugs you. She asks if you want someone to walk home with you. “No,” you say. “I’ll be OK.”

On the way home, alone, in the dark, you get scared. You run for seven blocks and stop crying. Even though you are running, your breath stays even. Your key is in your lock when your neighbor opens her door. “Hi,” she says, and she tells you her name. “I should have told you before.” You tell her yours. “I got a dog,” she says. You pet the dog and say good night.

During that week, your neighbor knocks. She has the dog on a leash. “Let’s go for a walk.” But the dog noses his way into your living room, whines and reaches his paws under the couch. Wrapped in tinfoil under there is the chicken that’s been missing from your refrigerator since the man was in your apartment. He must have thrown it there. A thigh with a bite taken out of it.

On the way to walk the dog, you drop the chicken in the trash.

During that week, your sister calls to see how you are. She tells you how hard it is for your mother to talk about it; how she hasn’t told your father, because she’s worried what it will do to him. “She has to tell him,” your sister says. “If she can’t, I will.”

But then your mother does tell him. She tells your father the next morning, and he calls right away. His voice has a slowness you aren’t used to. “Babe?” he says. “You OK?”

“I’m OK.” You want to be, for him.

He’s always called you girls “babe,” and you alone “sunshine,” his “brown-haired, brown-eyed girl.” When you were small, he held your hand wherever you went, even if it was just to feed the chickens or milk the cows. You’ve always hated breaking his heart.

Your father will be at the picture window. The wheat in the fields is coming to green. The swallows have finished a nest in the corner of the porch, mud drops dotting the siding below it. Your father sometimes wonders whatever happened to the martins, with their big yellow breasts, that used to nest in the yard when you were young.

“Your mother,” he says, “she wants to come down.”

“No,” you say. “I’ll come home in a few weeks. I want to get through the rest of the term.” Because if they come, you won’t be OK. It will mean that what your parents taught you about carrying on was wrong.

“Have they got the guy?” he asks, a snap and rasp in his voice.

“No,” you say.

You’ve never seen your father become violent. He never hit you, except once when you and your sister left a gate open, and a horse got into the grain and foundered; even then the way he hit you was so light that you giggled with your sister about it after. He won’t even kill the chickens he keeps for eggs and fryers; one of your brothers swings the ax.

“I’d like to kill him,” he says, “get my gun and your brothers and come shoot the bastard.”

His words come from many miles away, as though floating on blue smoke and the sunshine of early spring. The tightness in your chest starts to ease, and in your mind you see a scene, like one from a western: your mother on the porch sending the men off; your father and your two brothers walking shoulder to shoulder, felt-brim cowboy hats pulled low, long guns at their sides, almost hidden in the folds of their duster coats. Your posse.