All that fall and into the winter, bulldozers and cranes cleared away the wooded top of Ransom Mountain, knocking down trees and shoveling dirt and rock into dump trucks, leaving behind a flat, barren expanse. Come spring, we were told, the mountain’s top and back would be a landfill that three counties would pay to use, creating jobs in town for the first time since the mines had shut down. But no one I knew thought very much about that. When school let out, guys raced off to the record store or hung outside Hamilton Drugs and lit up cigarettes they had just turned old enough to buy, or else they went straight to their girlfriends’ houses before strict and suspicious fathers returned from work, if they worked.

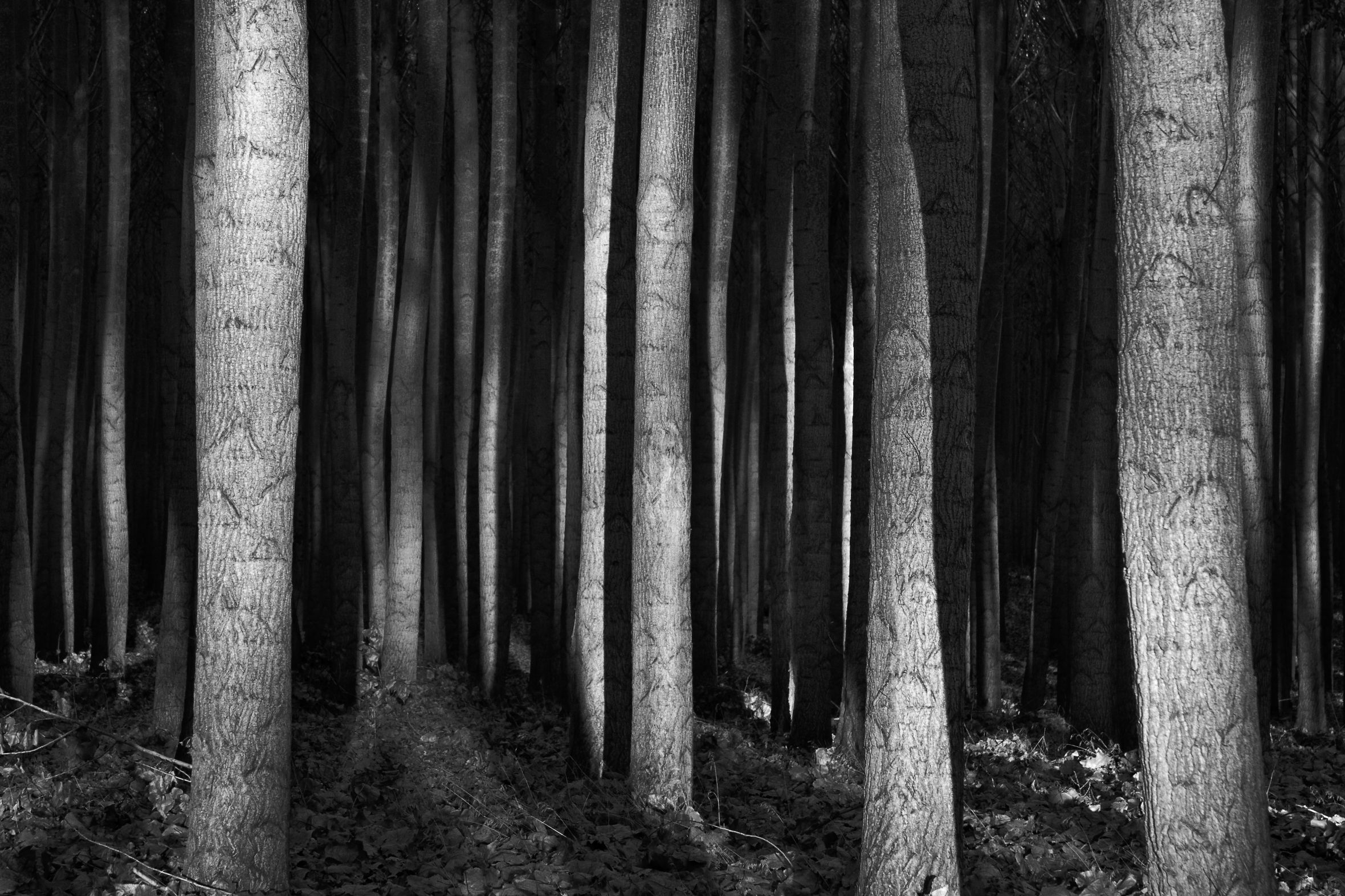

I had something of a girlfriend, too, Mikaela, who had gone by “Mickey” until right before the school year started. She was exactly a week older than I was and got good grades and would turn out as well as everyone expected she would, but through the heart of that winter I found one excuse or another for not walking her home. Instead I broke off from the others with Danny Noyse and headed up Coal Street, past the old mining-company houses — all of them exactly alike and crammed close together — where only elderly people lived, until the road tapered into a path that wound up Ransom Mountain. At the top we tramped through the woods and stepped into the wide, windblown, man-made clearing that, with its snow-filled craters, could have been on the moon. Our corner of it seemed forgotten, hidden behind a stand of white birch and scraggly pines, out of the way of the heavy machinery and near the boarded-up entrance to a mine shaft. There we dropped our book bags and stripped down to our undershirts and took off the gold crosses we wore. Danny stood no higher than my shoulder, but he already looked like a man, his reddish-brown hair receding, his face gaunt and lined. “Ready?” he yelled above the diesel engines and the sound of rocks clanging into deep, empty truck beds, and when I nodded, he clenched all his muscles and chuffed steamy breaths through his teeth, his veins popping. This was exactly how he looked when he flew for no reason into one of his sudden rages, fits that had been coming more frequently since his father had grown scrawny and pale with cancer, a secret Danny kept from almost everyone. “Do it,” he said, and I hit him as hard as I could — in the chest, in the stomach, in the ribs, over and over until my knuckles were raw.

I was not strong. I was tall and underdeveloped and gawky. A couple of months before, my father had taken me to the recruiting station to sign up for the army — because there were no longer any jobs around here, and if you were going to do OK for yourself, you had to find a way out; and because it would help pay for college, if and when I was ready to be a good student; and because my father believed that I needed to be taught discipline and toughness and motivation to make my own way in the world. Above all else, it was a plan to harden me.

“Again,” Danny said, and I hit him with everything I had until I was out of breath and it was his turn to hit me. We did this three, four, five days in a row, then took the weekend to admire our bruises and heal a little, and on Monday we went back up there. Once, Danny took off his undershirt, and I was awed and a little sickened by the purple bruises I had made. His chest looked the way I imagined his father’s lungs would look.

On that day we didn’t have the strength to pummel each other the way we wanted to and walked back toward Coal Street feeling weak and small. We could no longer hear the huge machines dismantling the mountain, and I thought about Danny’s father, who could barely walk anymore and never left the house. Soon he would be nothing, more nothing than the silence in those woods, more nothing than I was able to imagine. Of course the idea went against everything I had been taught by parents and priests since before I could remember, so I stopped trying to picture nothing and imagined my fists slamming against Danny’s ribs and chest. I tried to feel the satisfaction I believed he found in it, the momentary purposefulness when I landed one solidly, nearly knocking him over, and there was not pain, I imagined, but somehow nothing and everything at the same time, and his mind went thrillingly clear, like snow, like winter air.

“Tomorrow,” I said, trying to cheer him up as we went back down the path. “We just need another day to get our strength back up. Make sure you eat steak tonight. Tell your dad you have to have it.” A stupid thing to say. Danny walked on ahead of me, picking up his pace.

I have never been one of those people who believe they can control their fate. Maybe this is a sign of weakness, or maybe it’s a sign of good Christian faith. (The nuns from school would laugh to hear me talk about faith.) But either way it put me at odds with my father, who was a striver, having achieved his goal of finishing college before he was thirty — seven straight years of night classes — and commuting an hour to a job that was not only steady but gave him a chance to advance. Which is why I caused my father such consternation. He said, “We have to put an end to this aimless drifting. You can’t go your whole life this way.” He said, “You’re too easily swayed by the wrong people.” He said, “Maybe the army will help. I don’t know what else to do.”

We were by no means wealthy — our house, though it was one of the newer ones in town, was small and a little damp inside — but we were the most well-off family I knew. We lived south of Main Street, where homes were set back from the curb and shaded by tall trees. To get to Danny’s I had to cross Main and walk four blocks north on O’Fallon, parallel to Coal Street, on the edge of the company-built neighborhood: no trees, no lawns to speak of, just chain-link fences, some of which penned in dogs. Danny’s was the last house on O’Fallon and had room in back for a toolshed. When we were kids, Danny’s father had always been working. I would hear his chain saw from blocks away and follow the sound to the shed behind the house, where he would be plowing through a stack of firewood, lean and shirtless, a cigarette between his teeth, sawdust piling up around his boots. He was a good bit older than my parents, or any parents I knew. He told people he was retired, but my mother said he had worked in the mines until the company had folded, and he’d lived off the government ever since. She was wary of my spending time with Danny, who was the youngest in his family by fifteen years, born when the mines had closed. His mother had been institutionalized within eighteen months of having Danny. Some people said she was schizophrenic; others just called her crazy. By the age of five Danny had a reputation as a troublemaker; he was maybe ten when my mother saw him ride by our house in the back of a patrol car. There was every reason for me not to hang out with Danny, but as a kid I’d loved going to his house. I’d loved the sound of the saw, the smell of sawdust and motor oil. Danny’s father would always stop what he was doing to make me feel welcome and indulge me a bit. I remember once showing up with a toy badge pinned to my shirt, and Danny’s father laid a work-weathered hand on my shoulder and tilted his head back, squinting through the smoke from his cigarette. “ ‘Special Officer,’ ” he said finally, reading the badge. “Wow. You’re not here to bust me, are you?” Throughout my visit he made a show of tiptoeing into whatever room Danny and I were in and stealing one of Danny’s few toys so I could jump up and arrest him.

The other boys — the ones I had played baseball with, climbed Ransom Mountain with and lain belly down with next to the cliff, binoculars to our eyes, scouting for Indians or Nazis — they had turned cool and secretive. They smoked and shot eight ball at night, and at school talked about girlfriends and sex and drinking.

My relationship with Mickey had grown — if that’s the right word — out of childhood tadpole hunts and the games we had made up in the woods. There had been no declarations of love, just an easy extension of habit. So her requests that we do more things together came as a surprise. She also got her hair cut in a bob and started wearing skirts and talking about how she wanted me to be a “real” boyfriend. So that September and October, before I began climbing Ransom Mountain with Danny, we drank iced tea on my back deck or had our parents drive us into town to see movies or hang out at the park. Sometimes we’d sneak away to make out and get half undressed and touch each other.

Once, in her basement, Mickey lifted my T-shirt over my head and saw the bruises Danny had given me. She gasped and touched one, and I flinched. I told her I’d been roughhousing with Danny, no big deal, but she rolled onto her back and went quiet and sullen. When she had worked out her thoughts on the matter, she rolled back over, straddled me, and covered my ears with her hands. (This was how she said the things to me that she felt most deeply. When I asked why, she said that saying these things out loud made her feel like she was carrying a “really, really full glass of water across a crowded room.”) She looked me in the eye and spoke deliberately. Though I heard only muffled noises, I read her lips to say: “You have to decide.”

About what? I knew she hated my father’s idea of my going into the army. She probably wondered why I didn’t do what she was doing: earn good grades and win scholarships.

And I knew Mickey was wary of Danny Noyse. A week or so earlier, we had watched him fly into madness in art class, tearing up his drawing and making sounds like a boy reared by wild animals. Even after our teacher had restrained and calmed him, Danny shook uncontrollably, his face blotchy and red, and eventually he wept. It was not uncommon for him to start crying in class, silently and for no obvious reason. I had heard people say he suffered from whatever malady had felled his mother, and I had always accepted that as a fact, though no one ever bothered to find out what the malady was or if anything could be done about it, if Danny was in fact afflicted. All anyone knew was that his mother had been taken away. People kept their distance from him and talked about him with contempt. I could think of no one who liked Danny (though Mickey at least felt some pity). Even his oldest playmates had cut him off over his spontaneous outbursts or because he smelled bad or because their parents had insisted they do so. Anyway, I thought maybe Mickey wanted me to decide whether or not to keep spending time with Danny.

She removed her hands from my ears and climbed off me and lay back down. I could have explained that Danny’s father was sick, that he was dying, but I knew that only because Danny had let it slip one day. And so, to relieve him of the guilt for having revealed his secret, and to convince him I could be trusted, and to keep him from someday coming at me in a fit of violence, I’d agreed to hike up Ransom Mountain and see how hard we both could punch. But I didn’t tell Mickey any of this. I let the matter go. What could I have done about it anyway, whatever it was she wanted me to decide about?

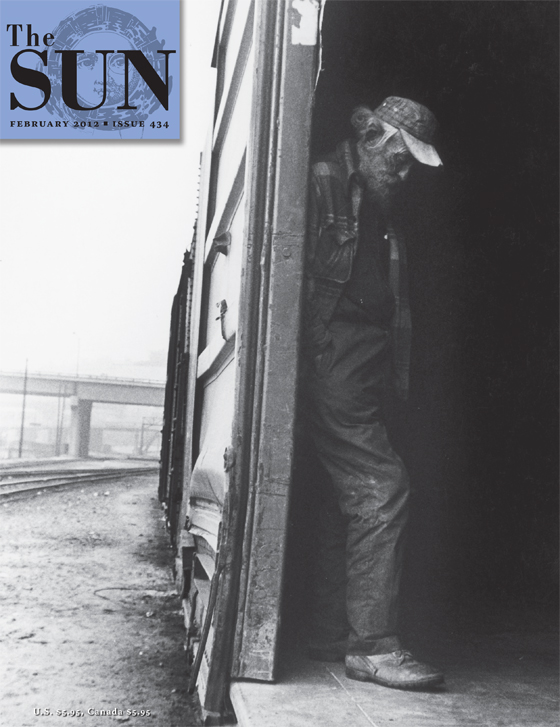

Once, Danny and I went into the mine. This was before Christmas break, when the bitter temperatures had made it that much harder to inflict and withstand pain, especially after we had both started taking the punches shirtless. That day, as we reached the end of the uphill path and the edge of the cratered clearing, an icy wind was blowing through my coat and sweater, and I hoped that Danny’s hands were as frozen as mine were, too stiff to ball into fists. Maybe they were, because he put his head down and walked against the wind until he had reached the boarded-up mine shaft. He kicked the middle board until it gave way, and I followed him. The boards were old and weather damaged and brittle, and we didn’t stop until we’d removed every bit of them, and then we took all the pieces into the mine. Without speaking, we both knew we were going to build a fire. We went back out into the wind and the cold to gather felled branches to use as kindling. Though it was almost dark, the bulldozers were still at work, expanding the clearing to the east, and beyond the far edge of the sheared-off mountaintop, stark against the soft gray overcast sky, a dingy orange crane dumped earth into the back of a truck that idled below the ridgeline, just out of view. I watched the crane as we scavenged at the edge of the woods: the strange, sharp angle of its arm, widening and narrowing haltingly. We could hear other cranes loading dirt and rock into other dump trucks down the backside of the mountain. The landfill, we were told, would be open in late spring, about the time I would head off for basic training to be remade into a soldier, whatever that meant.

Back in the mine Danny said, “We need paper. Do you have any paper?”

“No,” I said.

“What’s in your pockets?”

I pulled out three crumpled dollar bills. He took them and arranged the twigs and smaller branches around them, then added a couple of fragments of the boards we had kicked in. He did this expertly, with patience and diligence. Then, from a pocket inside his coat, he pulled a tin canister. He unscrewed its top and drizzled the contents over the complex scaffolding he’d built.

“You carry lighter fluid?” I said.

He shook his head. “Lamp oil.” And he tucked the canister back into his pocket. Then he drew a pack of matches from his sock, lit one, and held the flame to the dollar bills. In the first bit of firelight I saw the deep lines pulling at the corners of his mouth and the vertical creases that began high on his forehead and deepened between his eyebrows. No one else our age had lines like these, or so gaunt a face, or such thin lips. For a moment I saw Danny’s father’s face in his, but without the playful humor in the eyes. Danny bent near the ground and blew gently on his fire. We added wood until the flames reached higher than our heads.

I could see the topography of the rock walls, craggy and dark and damp. Beyond the firelight the mine was gaping blackness. Drips echoed from somewhere deep inside. Childhood playmates of mine had gotten in trouble for crawling into mines. I’d never been in one, though they were talked about all my life, a constant point of reference, a thing that defined us. They were the fate my father and Mikaela had worked so hard to avoid. I began to say, Can you believe that guys worked in here? but of course Danny’s father had been one of those guys.

“Did your father work in here?” I asked.

Danny snorted and made a face. He said, “This is a cat mine. The company ones were huge. They went straight down. Guys went into them on elevators. They were —” he spread his arms, considered the distance between fingertips “— huge.” He made a face, part anger and part bewilderment, as though he were mad at himself for not knowing the words he needed. I braced for a coming rage, but Danny took a deep breath and shook his head and picked up a stick to stir the fire with. We added more wood until the flames shot high and bright again. “They’re all cemented up now, the real ones,” he said. “They’ve been cemented up forever.” He set down his stick and stretched out his leg and pulled a knife from the pocket of his slacks. He unsheathed it to show me: the handle made from a deer antler, the blade short, no more than three or four inches, and freshly sharpened. “It’s stronger than the rocks,” he said. “Watch.” He searched the floor at his feet until he found a seam, angled the blade into it, and then half sawed, half pried the rock loose. “My dad gave it to me. He used it to see how good the coal was.”

I asked to see the knife, but the request made Danny uncomfortable. I could see the struggle on his face, but eventually he handed it over, handle first. I hefted it, trying to gauge its weight and balance. Though I knew nothing of knives, I doubted that Danny’s father had ever used it in the mine. It was too ornate, too new looking. But I also doubted my own sense of things and trusted Danny. I found a seam on the rock floor, one just wide enough for the blade to slide into, and I maneuvered it in as Danny had done, but the blade caught. When I tried to dislodge it, I felt the metal bend. Danny saw me panic and work the blade harder, and he dove for the knife, stricken and furious. “My dad just gave me that!” He put his hands over mine, fighting to take control, and the blade dislodged, jerking out of the seam and cutting through the heel of my hand.

I was afraid of what Danny might do to me as he lifted the knife to see how badly the blade was bent, but as soon as he saw the blood dripping down my wrist, his fit ceased, and he became concerned and ashamed, saying, “Did I do that?” He hurried out of the mine and came back with a handful of snow, which he used to wipe away some of the blood. Then he took my scarf from my neck and had me hold out my hand, and he wrapped it. “Come on,” he said, serious now, in charge, and I followed him out of the mine, the fire still burning behind us, a shrinking spot of undulating orange light in the darkness.

The path was all but invisible under the moonless sky. I kept pressure on the cut, and in the cold it didn’t hurt that much. When we reached Coal Street, I said, “See you later,” but Danny lifted his gloved hand toward my bleeding one and said, “I have to fix that.” I considered for a moment the wisdom of not going straight home, but Danny started along the fenced edge of someone’s property, heading toward O’Fallon Street, and I followed him.

His house was dark, not a single window lit up. Danny led me in the back door and closed it behind us very quietly. The kitchen was as black as the mine, and through the doorway to the living room I saw the glowing end of a cigarette. It brightened for a moment, then dimmed. Danny’s father said, “That you, boy?”

In the dark Danny was moving things around on the counter. He didn’t answer, so I said, “It’s just us, Mr. Noyse.” Then a match flared. Danny had found a camping lantern, and he lit it and turned up the wick. Along with the lantern he had a bottle of vodka. He unscrewed the top and poured vodka over a rag, soaking it. Then he said, “Let’s see your hand.” I unwrapped it, and he held it and felt along the edge of the cut. “It’s not that deep,” he said. It was amazing that he could tell in that dim light.

One day over the Christmas break, when all my bruises had faded and my hand was slowly healing, I spent the morning worrying about what kind of soldier I would make. I could not imagine how I, of all people, could become hard and disciplined. The thought of it made me antsy, and all the comforts of time off from school — sleeping in, lazing in front of the TV, overeating for the hell of it — felt vain and misguided, the empty pastimes of childhood, like toy cars or wooden blocks. All I wanted was to go up Ransom Mountain and give and take the hardest punches Danny and I had in us. But I had started to take some ribbing about hanging out with Danny and didn’t want to be seen crossing Main Street and entering the old miners’ neighborhood. So I went to give Mickey her present — I had ignored my mother’s advice to get her jewelry and bought her a record album instead — even though Christmas was still a couple of days away. Mickey’s mother answered the door and said Mikaela was out. I tucked the record under my arm and asked her to tell Mickey I had stopped by and for her to please give me a call so we could do something later. I went back home and waited, but Mickey did not call.

After supper my mother began cleaning up, and my father went into the den to watch TV. Still restless, I put on my coat and set off for Mickey’s again. From the street I could see her mother and father and brothers around the supper table, but no Mickey. I kept going until I reached Main Street, and I decided to stop in at Gavin’s, the tavern where some of my classmates had begun shooting pool at night. I had not been inside Gavin’s since I was a kid. My parents were not drinkers and were never very sociable.

Gavin’s has two rooms. The first is lit warm and cozy by red neon lights. If you are a young man, you open the door to discover you know everyone in the place. They are your parents’ friends and co-workers and your coaches and mailmen, and when you open the door, they all look up from the tables and bar stools they laid claim to thirty or forty years before. Behind it is a second room, where the pool table is. That is where you learn to drink and smoke and fantasize about what it might be like to be a man. Every now and then, one of the old-timers comes back into the other room, picks up a pool cue, and shows you how young and green you really are.

It was at Gavin’s that I learned I was no longer Mickey’s boyfriend.

When I came into the back room that night, Shep and Jimmy Manko and Percival were drinking beer and holding pool cues and chain-smoking inexpertly. They talked a little too loud, and their eyes were red and irritated. Shep and Manko were being shown what’s what by Eddie Curran’s grandfather and his pool-playing partner, Tom Mayes, who wore a baseball cap with the name of the aircraft carrier he had served on during World War II. When it was Shep’s turn, he let his cigarette burn in the corner of his mouth, lined up a shot, and smacked the cue ball a little too hard, remaking the whole landscape of the table. Curran’s grandfather chuckled and sank six balls in a row, ending the game.

“You want in?” the old man said to me, chalking up, but I shook my head, and the boys noticed me standing there.

“Hey,” Percival said. He lit a second cigarette off the butt of the first. “What happened to your hand?”

The cut had been healing, but it was still ugly. I told him a knife had sliced through it.

“Then you really need a beer,” he said. He slapped my shoulder on his way to the bar. In a moment he came back and handed me a can and a frosted mug, saying, “Cheers.” Percival was not someone who talked to me as a rule. I hadn’t seen him since he’d dropped out of school. Maybe he was lonely without it. In any case he was chatty. He shared his cigarettes with me and bought me beers, and we watched Shep and Manko lose again and again to Eddie Curran’s grandfather and Tom Mayes. Percival asked about my plans after graduation, and when I told him I had enlisted in the army, he nearly spit out his drink. “Really? I thought for sure you were going to college. Of all the people I know, I figured you and Mickey were the college types. I figured you’d be together forever, get married.”

“I still might,” I said, “after the army.”

“That girl’s going places,” he said about Mickey, and I agreed. “But I don’t know what she sees in Frankie White. I mean, he’s smart, but he’s such a . . . I don’t know. I just never thought much of the guy.”

I had never paid much attention to Frankie White. I’d certainly never considered him competition. He was outgoing and not terribly funny, and he wore pressed shirts and always looked neat. I suddenly began to fathom the gap that had opened between Mickey and me, starting when she began to present herself in bobbed hair and skirts and earrings and as a girl named Mikaela.

To soften the blow, I drank whatever Percival handed me and tried not to think about it. I remember being convinced to try my hand at pool. I remember holding a cigarette between my teeth and peering through the smoke and finding all the balls floating in and out of focus. I shot wildly, hitting nothing. At some point Percival went to the bar for another round, and while he was gone, the room wheeled, and I needed to leave. I put down my pool cue and made my way out the door and onto Main Street, and I realized I’d left my jacket inside. The weather was brutally cold, but I passed King Street, where Mickey lived, and avoided looking down it, and then came to my street and turned and had made it halfway to my house when I decided I wasn’t ready yet, that I had to take a moment to consider what had happened with Mickey and Percival and Frankie White and me. I sat down in the snow in the Weimans’ yard, alongside their hedgerow, to think. Already I understood that, though it hurt to learn that I was no longer her boyfriend, the bigger problem was that, without Mickey, my future was impossible to imagine. I tried to steady myself by flattening my hands on the snow-covered lawn and taking long, slow, deep breaths. The sky above me was vast and black.

When we returned to school, Danny was cool, remote, and preoccupied. We did not go up Ransom Mountain, and, for that matter, he did not speak to me. I admit I kept my distance from him, too, especially when I thought Shep and Manko might be around. Still, I expected Danny to approach me about resuming our game, or to wait for me when school let out. Instead, at the end of each day, he just vanished.

Mickey tried to seem as little changed as possible. She was polite and good-natured, and when she saw me walking ahead of her on the sidewalk or in the hallways, she’d call for me to wait. When I saw her ahead of me, I’d let her go on or turn and go in another direction. I never gave her the Christmas present, which I kept for a long time but never listened to. She did not tell me about Frankie White, and I never asked. I don’t know what good it would have done. Gradually she let herself be seen with him until everyone simply accepted them together, and I spent two or three nights each week at Gavin’s, learning to shoot pool and to pace my drinking. I took Percival’s advice about chewing gum or eating bread to cover the smell of beer, though it didn’t work. My parents, especially my father, thought graduation and the army could not come soon enough.

One day Danny seemed particularly distressed. I don’t know how else to put it. His face was blotchy and strange looking. Between classes, at his locker, he wept silently, and the usual bullies taunted him: “Are you crying, Danny? Why are you crying? ’Cause you’re a baby? A mentally retarded baby?” At lunch, in the crowded cafeteria, he snapped at one of his tormentors. I did not see it happen, but apparently he went after Jeremy Neal with his father’s knife, and he stabbed Jeremy’s arm, and Jeremy’s shirt blossomed with blood. I did see the teachers struggle to take Danny down and carry him — literally carry him as he kicked and thrashed and screamed awful, wailing sounds — out of the cafeteria and down the echoing halls to the principal’s office. Some hours later I saw him in his blue parka, the hood with the fake-fur trim pulled up, leaving through the school’s north-facing side door and heading home through the snow. The rumor, passed on with delight, was that he had finally been expelled.

In history I sat next to Mickey. She passed me a note that read, “Are you OK?”

I made a face and wrote back, “Of course.”

She answered, “I know Danny is your friend.”

I don’t know why that note made me so angry, but I shook my head and tore it up and stuck the pieces inside my textbook.

She then wrote, “You can’t go on forever trying to avoid me.”

I ignored her.

She wrote, “Our lives are changing. I’m figuring some things out for myself.” When I didn’t answer, she wrote, “You have to decide about your life. What are you going to be? Where? Doing what?”

What was this kick she was on? Frustrated and annoyed, I mouthed, “What the hell are you talking about?”

Her face flushed, but she went back to listening to the teacher and taking notes. Later she passed me another note that read: “You’ve already decided. I didn’t understand that until just now. I’m sorry for bugging you about it.”

The last time I saw Mickey, she had come into town from Massachusetts, where she lives now with her husband and kids, and she surprised me one evening when I stepped out of Gavin’s for a smoke. She had her daughter, shy little Rachel, by the hand. I was embarrassed by my cigarette and my work shirt with my name stitched over the pocket and the patch that reads: Keystone Sanitary. (I work for the company that operates the landfill.) And I was quick — too quick, I know — to point out that I was going to college at night, as my father had done, and that my girlfriend, who also works for Keystone, but upstairs in accounting, already has her degree. And I went on, embarrassingly, about how much I read and what books were my favorites. But Mickey seemed happy to see me anyway, and when she asked whatever happened to Danny, I watched her take in the news that he’d ended up in the army. We laughed at that — what else could we do? — and I told her that, the last I knew, he had made staff sergeant. Then we hugged goodbye, and I stubbed out my cigarette and watched her walk away. I did not go back into Gavin’s, even though I had a fresh beer waiting for me and quarters stacked on the pool table.

The day Danny was expelled, I stayed behind until the halls were quiet. By the time I left, it was growing dark. I went out the same door Danny had left by so I could cut behind Main Street and into the old miners’ neighborhood without being seen. From half a block I could see Danny’s house was dark. I banged on the front door, and when no one answered, I went around to the back, which was unlocked, and I let myself in and stood in the kitchen. It smelled of sickness and stale smoke. And Danny’s father’s chair was empty. There was a draft from one of the broken windows. I called for Danny, then for his father, but the house was cold and still. It felt like what it was: a place where someone had died.

I left and climbed the path up Ransom Mountain. It was fully dark when I reached the top, and a bitter wind came from the backside of the mountain, along the makeshift road the bulldozers and cranes and dump trucks had made. The wind came hard across the clearing, making my eyes tear. I had to duck my head to walk against it. As I reached what had been our spot, I wiped my eyes and saw that the bulldozers had expanded the clearing to the west, taking out the cat mine and the stand of birch and pines that had broken the wind for us. Now it was all freshly turned dirt and rock, a flat, open space like all the rest of the mountaintop, packed down by bulldozer treads. I did not see Danny. Not right away. When I did spot him, he was a shadow in the cab of the nearest bulldozer, dousing the seat and controls with lamp oil. Then he climbed down from the cab and threw the empty tin, letting the wind take it. I went to him, shouting his name, intending to stop him before he went any further, but then I saw his face looking up at me, the twisted mouth, his eyes swollen and red, his cheeks chapped by wind. He reached into his sock for his matches, but his hands were shaking and too cold to grip them. He dropped one after another, tears freezing to his face.

Was it a decision? It didn’t feel like one. It was just that all of Danny’s rage and grief and frustration — I felt it as though it were mine. The world was changing, leaving us behind, and he wanted it to go back to the way it had been before the bulldozers had come to clear the woods and fill the mines to make a landfill. So did I. I reached out and took the matches from him, and I climbed into the cab and turned my back to the wind and managed to get one lit before I dropped it on the oil-soaked seat and jumped down as the flames shot through. In the flare Danny’s expression was calm. Even as the fire rose hot and bright, he didn’t shield his eyes.