There’s a news story from yesterday — December 21, 2006 — about an Idaho man who pleaded guilty to the beheading of his wife. He was caught because he got into a traffic accident that killed two other people, and his wife’s lifeless head bounced out of his pickup truck and onto the road.

I’m sitting in my pajamas in my home in Bellingham, Washington, searching the Internet for reports of heinous crimes people have committed, so I can compare their misdeeds to the one my nephew Anthony has been accused of.

According to the police, Anthony killed his girlfriend’s toddler son, Alex. And not by accident.

I first heard about the charges over the phone from my youngest sister, Nursey, Anthony’s aunt. I call her Nursey because she’s a pediatric nurse and is hardly bigger than some of her patients. She called me from Idaho, where she and most of my family live and where the investigation into Alex’s death was unfolding. Crying so hard I could barely understand her, Nursey told me that Anthony had been home alone with two-year-old Alex while his girlfriend — whom I’ve never met — was at work. Around 3 AM the couple brought the little boy to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with subdural head trauma. The doctors operated, but Alex died in recovery. Within days my twenty-one-year-old nephew was charged with first-degree murder, the cause of death listed as blunt-force trauma to the head. The prosecutors theorize that Anthony shook or struck the toddler, or possibly pinched his airways closed, causing a fatal brain injury.

Now I’m trying to decide whether beheading your wife is better or worse than violently shaking or striking a two-year-old. Murdering your wife and driving around with her head in your truck certainly seems more depraved. I wonder if the relatives of the wife murderer are as brokenhearted over what he’s done as I am over my nephew’s alleged actions. Are they sitting around kicking themselves because they didn’t notice that he seemed a little off? I want to call this other family and ask them: Was he basically a nice guy, until he wasn’t?

The National Center for Health Statistics reports that the top three causes of death for children ages one through four in the United States are unintentional injury, congenital anomalies, and homicide. It’s hard to fathom how homicide makes this list at all. Yet, from what Nursey has told me, Anthony looks guilty of just that.

On my laptop I watch a news clip of Anthony’s arraignment. When he says he understands the charges against him, he looks and sounds petrified. Speaking to the television news in Idaho, the Ada County prosecutor contends that Anthony caused the boy’s head injury and that “the striking of the child might have gone on for a period of time prior to that child’s death.”

According to another news report, Anthony’s girlfriend, Alison (the child’s mother), and Anthony’s mother, Steffie (the sister between Nursey and me), both observed Anthony being rough with Alex in the past: The girlfriend says Anthony used to put his hand over her son’s mouth and pinch his nose closed to make him stop crying. Steffie claims Anthony would get frustrated with Alex and squeeze his cheeks hard enough to leave bruises.

Alison and Anthony at one point lived with Steffie, which explains why she was one of the first people questioned by investigators. Seeing Anthony’s own mother making statements against him gives the clear impression that he’s guilty.

The defense doesn’t yet have a voice in the media. The articles I find cover only the prosecutorial stance and discuss the potential for the death penalty. The prosecutor is trying to get the media and the public on his side. Anthony has inadvertently cooperated by having a scruffy beard in his mug shot.

Here is what I can piece together about the background of the case from Nursey’s phone calls and our older brother’s e-mails: Anthony went out with Alison for two stretches, and in between he dated another woman. He fathered a son with each of them. Alison gave hers up for adoption, which Anthony was unhappy about, and the other woman kept her child. While Alison and Anthony were split up, Alison became pregnant with Alex by another man, and after she and Anthony got back together, Anthony became a stepfather of sorts to her little boy.

I’ve also learned that this isn’t my nephew’s first run-in with the law: since the last time I saw him, Anthony has acquired a rap sheet. One of the black marks on his record involves the other girlfriend, who accused him of choking her during an argument. Anthony pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of battery and was sentenced to probation and ordered to complete anger-management classes. Then there’s an earlier charge of fighting (to which he pleaded guilty of a misdemeanor) as well as a charge of statutory rape (pleaded down to misdemeanor battery) of a fifteen-year-old girl when he was eighteen years old. My nephew’s record does nothing to help his defense.

But I still love Anthony. I visit the Ada County Jail’s website to learn how to send him money. While I’m there, I click around and find his photo: Shaw, Anthony G., number 641720. His full-color head shot is posted. The same photo has been in the news, but the resolution on the jail’s website is better. Anthony is wearing a plain white T-shirt, his brown hair cropped and ruffled. I stare and stare at the photo, and I don’t see a murderer. I just see my sweet nephew, his brown eyes and olive-toned skin dotted with freckles. The curve of his jaw reminds me of my brother, even with the silly beard. Because of where Anthony is now and why he’s there, most people who look at this picture will see just a mean piece of trash, and maybe I should, too. But instead I want to take him in my arms and rock him like a baby and cry with him over what cannot be undone.

I remember Anthony at his brother’s wedding five years ago. At the reception my sixteen-year-old nephew strutted around like a hotshot in his rented tuxedo, a white boutonniere pinned to his lapel. He was the best man.

“Dance with your aunt,” I ordered him.

He escorted me to the dance floor and did a decent job waltzing me around. I told him he looked handsome.

“I know,” he said, stepping back so I could admire him. His dark eyes sparkled.

“I bet you think all the girls want you.”

He sighed dramatically. The problem, he explained, was that there wasn’t a single girl at the reception who wasn’t related to him. He was right. The only girls anywhere near his age were two blond cousins in matching dresses.

“Then you’d better get yourself downtown in that tux,” I said.

He told me with a hangdog look that it was rented for only one night. We both started laughing.

How far back in Anthony’s life do I need to go to find that moment when things could still have gone another way, that millisecond when my likable nephew veered irrevocably toward this untenable present?

When Anthony was about eight years old, the family gathered at St. Mark’s Catholic Church in Boise for some religious holiday or confirmation or church luncheon. Afterward I was sitting on the wide steps at the base of the altar, and Anthony came and sat beside me.

He and I are the only olive-skinned members of the family, courtesy of our respective paternity. Maybe we bonded so easily during our brief encounters because we share this physical feature. Steffie, Nursey, and my older brother are actually my half siblings. They were raised by our biological mother, while another sister and I grew up in a different household. But we were all close. Steffie got pregnant for the first time in high school and went on to have three children with three different young men in fairly rapid succession. Anthony is the middle child, and my family considered his father “bad news.” When Anthony was very young, his dad received a prison sentence of nine-to-twenty for a cluster of crimes that included burglary and forcible rape. Was that the turning point for Anthony?

Sitting there with him on the altar steps, I wondered how my nephew was doing. I don’t remember what relative he was staying with at the time, but he hadn’t lived with Steffie for a while. I asked if he was OK.

Anthony scooted closer, so that our sides were touching, and said he was, but it didn’t come out as brave as I think he intended. I felt as if I should have been looking after him, making sure his hair got combed and that he was safe. Steffie had struggled growing up, whereas I had gotten all the breaks: gymnastics lessons, private schools, a mom who’d kept healthy food in the house, a father. I figured that I owed a debt of sorts to her — or if not to Steffie, then to her offspring.

While Anthony and I were sitting there, someone snapped a picture. Later I got a copy of it and tucked it into a book for safekeeping.

When Anthony was around thirteen, someone beat him up. He had bruises all over his body, my mom told me by phone. Anthony said it was his father, whom he was living with at the time.

My mom and I did not discuss notifying the authorities or getting Anthony counseling or even medical attention. When a family member informed a child-welfare agency, Anthony refused to talk about the abuse. I considered taking Anthony into my home, but I had problems to resolve in my marriage. So I did nothing. I didn’t confront his father and ask if he had done it. I didn’t check on Anthony. I didn’t even give it much thought. Since I never heard about any more bruises, I told myself it must have been a one-time occurrence.

Anthony and I have been writing back and forth since he’s been in jail, although his attorneys have advised him not to say much about his case. “Dear Aunt Laurel,” he writes, “I really miss everybody, I wish our family was closer, you know? I miss Alison and Alex so much it hurts. Even though Alex wasn’t my blood, he was my son.”

Nursey and I talk on the phone about whether to reach out to Alison. Her grief must be staggering. We don’t want to be uncaring, but we’re not sure whether a gesture from Anthony’s family might be perceived as an attempt to sway her testimony. We are stunned when Alison is arrested and charged with felony injury of a child for having left Alex alone with Anthony. The newspapers run another spate of stories about the case, now harping on how Alison allegedly knew of Anthony’s cruel tendencies but failed to remove her son from harm’s way.

A Boise television station posts Anthony and Alison’s mug shots side by side, like Bonnie and Clyde. I study Alison’s long, straight hair, the slight dimple in her chin, the one front tooth that’s longer than the rest. This beautiful young woman is a stranger to me, yet her fate is bound to my nephew’s. Her future seems as bleak as his, and no matter what the courts and jails do to her and Anthony, nothing will raise that child from the dead.

In the springtime I head home to Idaho to visit Anthony in jail. He’s still in the county lockup, in limbo before his trial.

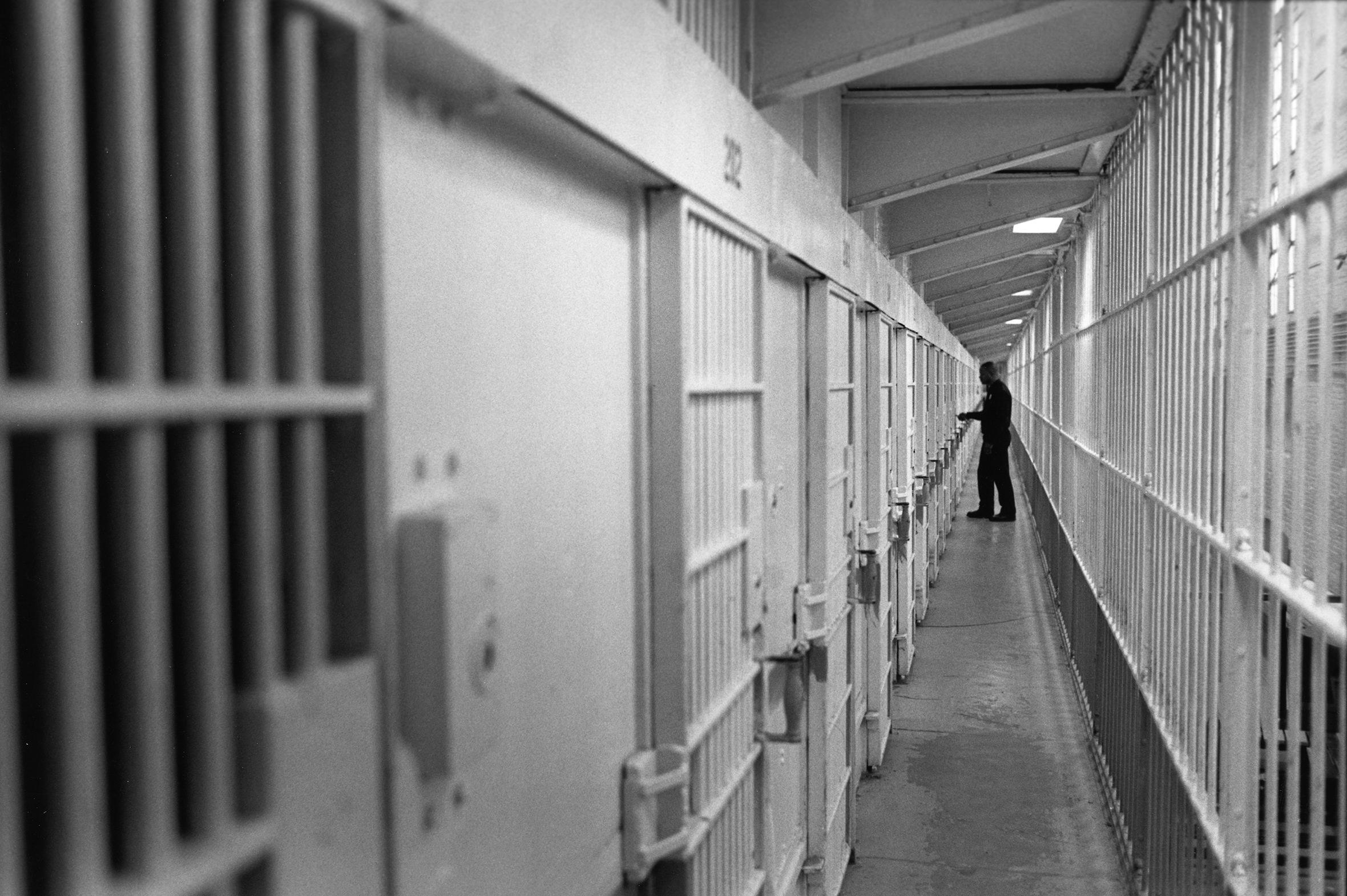

Ada County Jail is nestled among two neighborhoods and a shopping mall, less than a mile from the Catholic high school I attended before I stopped believing in God. Nursey has come with me. She holds my hand as we’re led down long hallways to a room where visitors line up in front of cubicles and wait for prisoners to appear. Anthony comes out wearing an orange jumpsuit. I know from his letters that this means he’s been “promoted” from yellow, which is maximum security. Still it’s shocking to see him in jail attire. Nursey and I go into one of the cubicles and take up the phone on our side of the glass. We sit together on the plastic seat, cupping the receiver between us so we can each listen with one ear.

Having no privacy whatsoever, we don’t talk about the looming trial. Anthony gives us a rundown of jail life: He shares tight quarters with several other men, but they’ve learned to give each other space where there is none. He chokes down the terrible jail food. The guards regularly search the cells for contraband, such as the origami some of the men fold to pass the time.

I ask how origami is contraband.

“Anything you modify,” he replies.

Nursey takes the receiver from me so she can tell Anthony about her new job in Salt Lake City. I try to take it back, but she won’t let go. We pretend to fight over the phone, and then we’re all laughing and making jokes. For several precious minutes we aren’t in jail; we’re just sitting around, cracking each other up. When the guards step in to say the visit is over, I can’t believe an hour has passed.

I return home to Washington State, where I get somewhat used to the idea of Anthony being in jail. True to form, our family does not gather to discuss his guilt or innocence or whether we should come up with a strategy to help him either way. He is represented by a public defender, and we passively wait to find out what will happen.

The case against Anthony starts with the fact that he was home alone with Alex on the night the boy began throwing up and growing unresponsive — that and Anthony’s “history of violent behavior,” as one news station terms it. In addition to his police record, all of Anthony’s supposed transgressions in the months preceding Alex’s death are detailed in a series of memorandums filed by the prosecutor’s office: Anthony is said to have slapped Alison when she tried to throw away some marijuana that belonged to him; while living with his sister, he allegedly slapped her oldest daughter for touching his DVDs; he allegedly slapped both Alex and his sister’s daughter when the children fought over toys; he had unreasonable expectations for Alex’s behavior and development.

One memo contrasts Anthony’s apparent caring feelings toward the child he fathered with his other girlfriend and his reputed cruelty toward Alex. It seems to me the argument could just as well be framed to say that Anthony’s behavior toward his biological child is an example of his kind disposition. I think back to Anthony as a boy, holding his kid sister’s hand, looking out for her. I’ve never seen him do anything mean.

I reread a news report from December 14, two days after Alex died. The Ada County coroner reported that Alex died of blunt-force trauma to the head twelve hours after being admitted to the hospital, but the cause of death wasn’t listed as homicide; instead it was “pending investigation.” One week later Anthony was charged with murder.

The choice seems too obvious: here was a young man with a spotty past and people willing to speak against him, and he’d been the one home with Alex. Although it isn’t mentioned in any of the news articles I’ve read, I wonder if Anthony’s father’s criminal record biased the police and prosecutors against him.

I call Anthony’s older brother, Lee, whom I view as levelheaded and honest. He says Anthony often held Alex and played with him. He also tells me that, according to Anthony, little Alex had been jumping on the bed a few days prior to his death and had fallen off and hit his head.

“Babies’ heads aren’t that hard,” Lee says.

I think of that jump-rope rhyme: “Ten little monkeys jumping on the bed. / One fell off and broke his head.”

The strain on the family shows. I start to dread e-mails from my older brother, because each missive delivers worse news: Our biological mother has suffered a fall, fracturing her arm at the shoulder joint, and it isn’t healing well. Steffie has been committed to a state mental facility. Nursey, who has eating disorders and has been dependent on prescription medications for the last year, makes a suicide attempt. After helping her sign into an inpatient clinic, her husband files for divorce.

My brother looks after our mother. I travel to Utah to spend time with Nursey, who’s down to eighty-four pounds. Anthony’s case drags on, and I feel my hopes sinking. Will there be any of us left standing by the time this is over?

At last the defense makes a key move: soliciting an out-of-state forensic pathologist with expertise in head trauma to review Alex’s medical and autopsy reports. I get a copy of the forensics report from my brother. I only skim it at first, because it’s too painful to imagine this tiny child being subjected to an autopsy. But after putting the report down several times, I finally read it carefully: “A diagnosis of ‘non-accidental injury’ or ‘abusive head trauma’ is a legal, not a medical, conclusion,” the forensic pathologist states. Based on his analysis of tissue slides received from the autopsy, he makes a determination that subdural bleeding occurred three to four days prior to death. The pathologist’s professional opinion is that “progressive and continued bleeding in an established SDH” (subdural hematoma) caused Alex’s symptoms on the night he was in Anthony’s care. He goes on to state that a child of Alex’s age, with a “non-rigid infant skull,” can incur internal head injury from an apparently innocuous and low-velocity impact. The report summarily dismisses the possibility that Alex’s injuries could have been caused by violent shaking, stating that shaking force is transmitted through the neck, and that the neck “fails structurally at acceleration considerably lower than that required to cause SDH.” The autopsy had revealed no evidence of neck damage.

I should feel relief at the pathologist’s conclusions, which indicate that Anthony and Alison may be guilty merely of failing to realize the seriousness of Alex’s injury after his fall. But the boy is still dead, and my nephew is still being held accountable. Having grown up in a family that’s used to bad news, I previously accepted his guilt. Now I’m not so sure. I wonder how much the family’s muddled reactions to the case have worsened Anthony’s chances. Only a few relatives spoke against him, but it’s not as if the rest of us protested outside the jailhouse to proclaim his innocence.

After the forensics report is submitted, the lawyers for both sides negotiate, and the prosecutor offers Anthony a deal: plead guilty to the reduced charge of second-degree murder in exchange for a possibly shorter prison term and no risk of the death penalty. After conferring with his attorneys, Anthony takes the bargain.

I read a batch of reader responses to the plea agreement on the Idaho Statesman website, including one suggesting that Anthony be shot in the head and the bill for the bullet be mailed to his family.

It’s December 12, 2007, exactly one year after Alex died. I force myself to do something I haven’t been able to do yet: look at the small boy’s picture for more than a few seconds. The one I have is from an online obituary. He’s settled against a cushion. His thick, jet-black hair is combed forward, and wispy bangs cover part of his forehead. His full lips are pursed as if he’s about to blow someone a kiss. His eyes — big, round, and dark — gaze right into the camera.

I try to get a sense of this boy. Cute. Probably wiggly. Smart, I think. I know so little about small children — when they walk, when they talk, when they go from diapers to training pants. I want to think this boy hit all those milestones early.

Today is also the celebration of Our Lady of Guadalupe, an appearance by the Virgin Mary on the hill of Tepeyac near Mexico City in the sixteenth century. I very much want to believe in the Virgin of Guadalupe. I want to believe there’s a place for the souls of innocent babies to go, and that she’s there to take Alex by the hand and walk beside him.

Nursey has hanged herself. A maintenance worker at her apartment complex found her early this morning swinging from a balcony beam. She used her terry-cloth bathrobe belt as a noose, and she didn’t leave a note. I call the airlines to buy a ticket to Fresno, California, where she had been living. Her two best friends have offered to meet me there over the weekend to help pack up her belongings.

The next day, as I’m making arrangements for Nursey’s funeral, Anthony has his sentencing hearing. His brother, Lee, fills me in later: A lot of time was spent on testimony about Anthony’s prior criminal record. The prosecution showed a picture of Alex sitting on Anthony’s lap, looking unhappy. Some of the original character witnesses were called up to testify for the prosecution. One was an ex-husband of Steffie’s who, according to Lee, bore some ill will toward Anthony’s father and, by extension, toward Anthony. (Steffie had been declared incompetent to testify.)

Anthony’s attorneys negotiated for a life sentence with the possibility of parole in ten years, telling the judge that Anthony had had a “horrific” childhood and an unstable home life but could still learn to be a contributing member of society.

In the afternoon Judge Michael McLaughlin sentences Anthony to twenty-five years to life. The Idaho Statesman quotes the judge as saying that when an innocent child is murdered, the punishment will be “swift, sure, and lengthy.” Brought before the same judge the following day, Alison receives two and a half to ten years.

In the space of three days Nursey has taken her life, and Anthony’s and Alison’s lives have been demolished over a crime I’m now pretty sure was never committed. I sit, feeling useless, on the worn parquet floor in my kitchen, telling myself that I’ll cry just as soon as I figure out whom to cry for first.

In the summer I gas up Nursey’s beat-up Jaguar, which I received from her estate and haven’t been able to part with, and drive to Anthony’s new prison home in Orofino, Idaho: four hundred miles across dusty central Washington and into a section of Idaho’s panhandle that I haven’t previously had cause to visit.

The prison is on a hill at the south end of town. The building was an old state school and mental hospital before being converted to its present duty via the addition of a new wing and lots of barbed wire. In the waiting room I clutch my plastic baggie of coins for the visiting-area vending machines. I’m surprised by the friendliness of the attending deputy, a fiftyish woman who calls the inmates “residents” and obtains approval from a superior to allow me to begin my visit early because of the distance I’ve come. She leads me upstairs to a room that resembles a school cafeteria — except the tables and stools are bolted to the floor and a wall-sized one-way mirror allows unseen guards to monitor every movement.

Anthony is let in through a door. He hugs me and asks if I’m all right, as if I were the one locked up. Perhaps my expression gives away the tears I won’t let out. I want to grab his hand and run, knock aside the deputy who has been so pleasant and see if we can make it through the front gate and away in Nursey’s car before anyone can catch us.

Instead I dangle my bag of change.

“Wow, money,” Anthony says.

We’re both silent. Maybe we’re thinking the same thing: about how much of life he’s missing, how much the world will be transformed by the time he’s eligible for parole.

We make a small feast of vending-machine food. Anthony has to stay seated on his stool, so I go back and forth, fetching items and heating plastic-wrapped cheeseburgers in a microwave. Other visitors and prisoners enter and take seats at the tables.

I ask Anthony a question that has bothered me: What happened with the other girlfriend, the one he was accused of choking? He tells me that he got angry with her for being reckless with her health while pregnant. They argued, and he punched out a window and spit on her. He did push her, but he never hit or choked her.

The visiting room has decks of cards, and we halfheartedly play gin rummy while we talk.

“My sis came to see me back in Boise,” he tells me.

I ask how it went.

“She acted like she was going to cry. But I started joking with her, and then she didn’t.” She told Anthony that she was sorry for jumping to conclusions about him. Anthony says there were inaccuracies in the news reports. Some said he and Alison stopped on the way to the hospital, but they didn’t. They went straight there.

I don’t respond, hoping he’ll keep talking. He says more about Alison, who is now in prison herself. She lived with her mother at the time Anthony began dating her. The mother liked him but forbade him to stay overnight at their house. One night he and Alison fell asleep on the trampoline in her yard, and her mother came out in the morning and threatened to turn the sprinkler on them: “Alison told her, ‘But Anthony didn’t stay in the house.’ ” We smile.

He tells me that while Alex was being treated at the hospital, the police questioned both Alison and him — routine procedure, they said, but a friend of Anthony’s advised him to get a lawyer, because they were going to accuse him, and of course that’s exactly what happened. “Alison said she knows I didn’t do anything. Her mom wrote this long letter telling the judge I wouldn’t have done anything to hurt Alex and that they shouldn’t lock me up.”

It’s finally time to be blunt, so I can at last see my nephew’s reaction, gauge it for myself. I think he’s innocent, but I need to hear him say it. I straighten on my stool. “At the time, I thought you did it,” I say.

Anthony jerks back as if I’ve hit him. His eyes grow wet, but he meets my gaze. He doesn’t protest or get angry or give me his version of the events on the night Alex died. He just says, “I understand.”

His resignation moves me. He hasn’t judged me for unfairly judging him, and I wonder at this young man before me, who has learned to expect so little from life. I look around the room at the other men huddled at tables with visitors, as if they will give me the answer, or the question.

The only fall Alex took, as far as Anthony knows, was the tumble from the bed.

“He did hit his head pretty hard, but we thought he was all right.”

“I’m sorry,” I tell him.

“I miss him,” he says.

That was six years ago. Anthony has since been relocated to a prison in Colorado. I recently got a letter from him requesting a pillow and a blanket. He rarely asks for anything. Usually he sends me gifts: drawings, cards he makes, a little blue bear he crocheted.

Periodically someone in my family will say, “We should do something.” We talk about the unfairness of it, but we don’t act. We are weighed down by inertia, or we have other troubles and joys to attend to, or we’re too self-centered to take on a battle we expect to lose.

Repeatedly I fall back on my memories for comfort: There’s Anthony dancing in a tuxedo at his brother’s wedding. There he is smiling at Nursey and me through the glass wall at the jail. There he is huddled next to me on the altar steps inside the big church. The other day I looked for that picture of the two of us, but I couldn’t find it.