It’s pizza night. Dad went to pick it up, and my mother is using our time alone to take subtle jabs at me, encouraging independence.

Do something, she says, frantically looking for her glasses. You can’t just do nothing forever.

How long have I done nothing? How long have I been living here? Her glasses are on her head, but she finds another pair in the side-table drawer and puts those on. The televised presidential debate is on in the background of this conversation we are having about my future. I’m not sure my mother cares enough to vote. I might. At least, I tell myself I will.

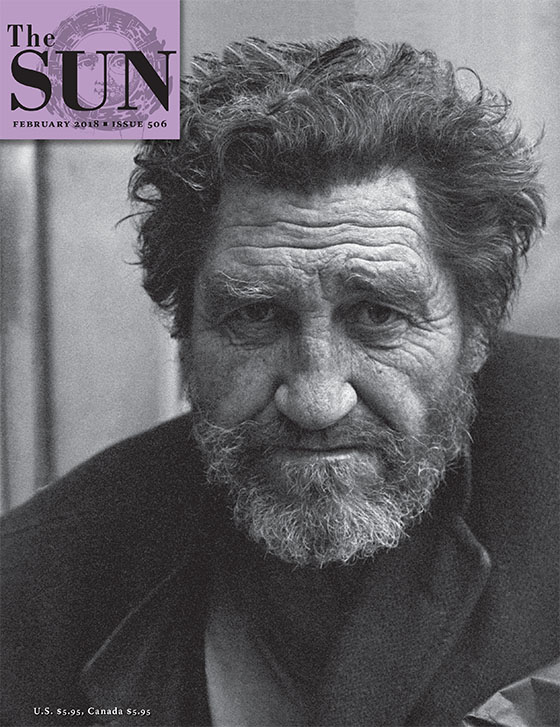

This isn’t how I pictured my life. I’ve been staying with my parents since my divorce. My father is home most of the time. He’s growing a beard and seldom wears anything but sweat pants. What’s left of his hair is wild. He watches daytime television and only complains a little about his aches and pains. My father worked hard until he couldn’t anymore. A stroke. Then another. What he has left is a plan for him and my mother to move to Florida.

The house is nowhere near ready for market. Somewhere along the way my parents have become pack rats. My father holds on to newspapers. Piles of them, stacked in order, take up about a quarter of the living room. My mother says she doesn’t mind. She says it’s good to have hobbies as we get older. I didn’t know hoarding was a hobby.

My mother is just as bad. Ever since TJ Maxx opened up in town, she can’t seem to stop buying stuff: Clothes in her size and in the size she wants to be. Candles. Fancy-looking jars and containers. Presents she plans to put away for Christmas but will forget long before that. Most of the purchases don’t make it out of the shopping bags. There’s a guest room you can’t even walk in. She keeps the door shut.

All this will have to be cleared out for them to sell the house. If they want top dollar in a competitive market, my mother says, the house also needs paint and central air. These are “selling features.” She wants to make sure the home sells quickly when they are finally ready. It’s pretty much all they talk about.

I try to imagine my childhood home with central air and no fans wedged into open windows. As kids, my brother and I used to talk into those fans to hear our voices sound like Darth Vader. My brother thinks selling the house is no big deal. A lot of people move to Florida when they get older. My brother’s got a wife and two kids and central air. I’ve got an ex-husband and my childhood bedroom. My brother’s room is now the guest room, but mine has been preserved like a time capsule of my youth. There’s a poster of 1980s heartthrob Kirk Cameron above the bed and a desk drawer filled with scrunchies. The elliptical machine in the corner is new. I don’t think anyone ever used it, but it was bought with good intentions, I’m sure.

My mother thinks I should look for a job. Really look. Jobs is one of the big topics in the presidential debate. One candidate interrupts the other, but the moderator quickly puts them both back on track. My mother fails to see the link between the local unemployment rate and my current situation. She saw an ad in the paper for part-time help at a nursery. She has pulled out the sparse help-wanted section and circled the listing in blue pen. She holds it in front of me, but I hardly look at it. When I tell her I’m not good with kids, she says we’re talking about a plant nursery — the place that sells Christmas trees every winter.

My father comes home with pizza. The TV debate gets muted, but I continue to watch the candidates’ dramatic hand movements. My dad’s got a favorite and a bumper sticker to show his support. Party loyalty. My mother tells him about painting the house and putting in central air as he sets the pizza on the table. He says yes to both, though she wasn’t really asking. We get pizza every Friday, same as when I was little. Who says you can’t go home again? The pizza is covered in mushrooms, just as it always was. I still hate mushrooms.

“You think our Mary has a green thumb?” my father asks my mother. He takes the first slice, chuckling to himself about what he just said. I take a slice and start to pick the mushrooms off. “Just eat them,” he tells me.

“I think a job would be good for her,” says my mother, always the last to put food on her plate. “Have you left the house today?” she asks me as soon as my mouth is full.

I haven’t. There’s nowhere I need to be. My mother has had a long day of trying to convince teenagers that literature is important. Though she should know better by now, she thought maybe this year’s students would like Catcher in the Rye. Some of them read it, she thinks. She’s not sure. She’s also not sure how to use most of the features on her smartphone. These things trouble her.

“I’ll check the ad out,” I say, reaching across the table for the two-liter bottle of Diet Pepsi.

“I want you to do more than check it out,” my mother says. She didn’t always look so old. A lifetime of facial expressions has left permanent creases. She keeps her hair short, sets it in hot curlers, and parts it on the side. “I want you to get the job.”

I married Dave shortly after grad school, which saved me from teaching English like my mother. He and I lived off artist grants and the money his marble sculptures brought in. The bank in town bought one: a four-foot bear in the lobby. The bear looks angry, ready to attack. I don’t understand how this helps the bank’s business. My whole family hates the bear in the bank. My whole family hates Dave.

Dave was a drinker, so I became a drinker. I matched him until I couldn’t keep up anymore. I think that’s when I stopped loving him, but our routine went on for a bit longer: cheap wine with breakfast, followed by cheap vodka and headaches and fighting and lovemaking. After I left him, Dave did not stick around. He packed a bag, took off on his moped, and sent divorce papers from two states away. We haven’t talked in a long time. I imagine he has a new muse and drinking partner.

Now I’m seeing Randy, who only drinks socially and coaches Little League. He says he just loves the game. Randy’s not much more of a catch than Dave. He works at the convenience store where Dave used to buy beer and scratch-off tickets. The level of authority Randy projects when wearing his red vest at work is heavily inflated. He says the job is just temporary. This town is temporary. Randy thinks he belongs in Hollywood. He’s been writing a screenplay for two years. I haven’t seen it. Randy tells me he wants me there with him when life gets better. He dreams big, like he’s not middle-aged and balding. When he wears a hat, though, you really can’t tell. He used to be attractive. He was never meant to get stuck here.

“OK, OK. I will work in the nursery,” I tell my mother.

“You have to get the job first,” she says.

“If Mary says she is going to work in the nursery,” my father declares, “she’s going to work in the nursery.” He reaches for another piece of pizza and tells me to make sure I set up direct deposit for my paychecks after I get the job.

Then my mother starts talking about my student loans: like they’re some kind of illness I picked up — a bad case of earning a degree. Debt sickness is a real thing, she assures me. They are remortgaging the house to pay for the repairs and upgrades but believe they will make the money back and then some when the house sells. My mother says they are buying a “lifestyle.” They won’t have to shovel snow in Florida. They will move into retirement housing for sixty-five and older: Shuffleboard. Bridge. Painting classes. Sunny days. A fresh start with no potential for anything to go wrong. My parents are leaving the nest, which means I will have to leave it, too.

On Monday I go down to the nursery. It feels like my life is somehow over but I’m still going through the motions. I don’t stop for gas when the warning light comes on. I’ve been ignoring warning signs for a while, or maybe I just miss them. Randy wants to meet up and celebrate after my job interview. He told me he has a good feeling about this. I try to think of the last time I had a good feeling about anything.

The nursery has a small shop, a few greenhouses, and a ton of land for all the Christmas trees. The kid at the register has bad acne and body odor. When I ask to see the manager, he yells for Bob. No answer. The kid yells again, louder, and Bob emerges from the gardening-tool section.

“How can I help you?” he asks.

“I called about the job,” I reply.

“Come with me. I’ll show you around.”

Bob takes me down every aisle in order. He’s a little heavy but walks fast and gets around just fine. We go out back to one of the greenhouses. It’s bigger than the store. I can hear the buzz of trapped bees. Bob says they’re harmless; he’s only been stung a few times.

“You will be responsible for watering all the houseplants. They don’t need too much water. Do you sing?”

“What?”

“Do you sing? It’s good for the plants.”

“No, I don’t.”

“Well, I’m going to need you to sing.” Bob looks like he’s waiting for me to break into song.

“Now?” I ask.

“Yes, now,” he says. “I need to know you’re cut out for this job. I’ve been singing to my plants for twenty-five years. Can you give me something jazzy?”

“I don’t think I can.”

“Just show me what you’ve got then.” Long silence. “Come on,” Bob says.

We’re standing by a cluster of African violets with emerging buds: my audience. I’m not a singer. Not even in the shower. But I do want the job.

I start to sing “Happy Birthday.” Bob stops me. Plants don’t have birthdays, he says. How about some Beatles? Bob starts the one about how he saw her standing there and he’ll never dance with another. Plants don’t stand or dance either, I want to point out, but instead I join in weakly on the second chorus. I can start tomorrow, he says.

Randy congratulates me when I call. I tell him that I am a plant singer, and he laughs and says it sounds like a fun place to work. I mention that I get a free Christmas tree every year. I guess every job has its perks, even though everyone hates theirs. Randy hates his job. My mother hates her job. My brother hates his job, and his wife hates her job. My dad, however, misses going to work.

Randy gets off at six. We make plans to meet at the bar down the street from my house.

It looks like it’s going to rain. My gas light is still on, but I don’t feel like stopping. I know I can make it home. I’ll stop later.

“Did you get the job?” my father asks when I walk in.

“Yeah, I got it.”

“And what will you be doing?” he asks, eager to hear about my new career path.

“I’ve been assigned to houseplants,” I tell him.

“Houseplants. Neat,” he says. “You can learn a lot by taking care of something.”

My mother joins in the parental praise. I don’t see the big deal. It’s not like I’ve never had a job before. I worked at the bookstore in graduate school. I’ve been a waitress at a bunch of places. I was going to apply for teaching positions when I was with Dave, but the idea of having so much responsibility so early in the morning seemed overwhelming, and I didn’t bother taking the certification test. I never really wanted to be a teacher. I think I just wanted to be like my mom.

“Are they going to train you?” she asks.

“I doubt it. There’s not much to watering plants.”

The mortgage broker is coming by the house later, Mom says. There are a bunch of papers they need to sign. Small banks with big bears in the lobby still make house calls apparently. My mom has baked cookies. The house smells like someone else’s childhood.

“I’m going out with Randy tonight,” I tell them.

“I saw him earlier today,” says my dad. “Stopped in for milk and a quick pick for the Mega Millions.”

“You bought a lottery ticket?” I say. I guess it’s not that weird. He’s just never done it before.

“You never know,” he replies. “Hopefully the guy from the bank leaves before the numbers are announced.”

My mother thinks the lottery ticket is just silly. She puts little stock in anything my father does these days. He forgets most of what she asks him to do. Now that I have a job, she’s already on him about doing something with his free time. She suggests writing.

“What would I write about?”

“Your life and your experiences. Or just make something up,” she says.

“Well, if we win the lottery, I won’t have to do anything,” he replies.

“You’re already not doing anything,” she says.

He pulls the lottery ticket out of his pants pocket. It even looks like a loser, crumpled around the edges, a crease through the center from being in his pocket instead of in his wallet. It’s hard to imagine the first lottery ticket he has ever bought will be a winner, but it would be great if it took care of their finances and gave them more options. There are nicer parts of Florida, closer to the beach. Their later years could feel more like a vacation.

“You could rip that ticket up right now, and it would have no effect on our lives,” my mother says, watching my father try to smooth it out. I can see this upsets her more than it should.

My father puts the ticket into his shirt pocket this time. “You know, you’re not right about everything,” he says.

If I take my car out again, I’m going to have to stop for gas. So I leave on foot but forget to bring an umbrella. The sky looks angry, swollen. Dark clouds have blocked the stars and the moon. I feel a few drops and walk faster. Randy will give me a ride home.

At the bar I find him playing darts in the back room. He’s got five bucks riding on the game. He throws and misses the board completely, then smiles and calls me bad luck. He wants a rematch: double or nothing. The bartender brings over three Bud Lights.

I lean against the wall and drink my beer. Randy is really bad at darts. The new match should be quick.

“Why did you sell my dad a lottery ticket?” I ask him.

“Everyone’s buying them. The jackpot is up to $27 million.”

“Do you think it means he’s desperate?” I ask.

Randy throws and makes it on the board this time. “I think everyone’s desperate.”

“I’m not,” I tell him.

“Says the singing flower girl.”

“And my father’s not either. I don’t want you to sell him any more lottery tickets. He doesn’t need to be wasting his money on that. And it’s just going to upset my mother.”

“I sell chances. I don’t take them away,” says Randy, missing the board again.

Randy is nothing like Dave. He’s not an artist and lacks the sporadic fits of ambition Dave would get. I’m not even sure he’s written a word of his alleged screenplay. He doesn’t like to talk about it. We fight differently, too. Randy can laugh off just about anything. Dave didn’t laugh. He drank and made art. And I’m sure he loved me. A while back I heard through a friend that Dave’s liver had been hurting, and he was looking for a good doctor and a good woman to save him. I wonder if he has found either. I don’t plan on seeing him again.

Randy tells the bartender that the place needs karaoke because I am a famous singer. He winks at me and throws another dart.

“You sing?” asks the bartender.

“Not really.”

“She had to sing at her job interview, and she got the job,” says Randy.

“Where will you be singing?” asks the bartender.

“Nowhere. It’s nothing.”

“And now she can save some money and get her own place,” says Randy.

“Who do you live with now?” asks the bartender.

“No one, really.”

“Got to love a mysterious woman,” says Randy, and he makes a few good throws before his losing streak reappears.

Randy asked once if I miss my independence. I didn’t know quite how to answer. He warns me all the time that rents aren’t as cheap as they used to be, and I might want to look for roommates. He’s never offered to be one of them. He thinks you can be independent only by living with other independent people. Living with parents doesn’t count. My independence is in a storage unit that costs fifty dollars per month.

I watch Randy play darts for an hour or two. The bar is somewhat full now, and there are a few guys waiting for the dartboard. The bartender says it’s busy for a Monday. All the regulars are here.

Tanya is sitting by the beer taps. She’s told me before that, geographically, it’s the best place to get free drinks: Guys always feel like they need to check out what’s on tap, even if they’ve seen it a hundred times and always get the same thing. And there she is, wearing jeans with rhinestones on the back pockets, waiting for someone to buy her a shot. She used to go out with Randy in high school. She was a cheerleader. When she sees him now, she runs over and leaps into his arms. I wonder if it’s OK for me to be mad that he catches her.

“Mary,” Tanya says to me after she lets go of Randy.

“Tanya,” I say back to her.

Randy says her flirting is harmless. He says Tanya is a real “hands-on type of girl.” That’s it. It’s nothing. Tanya goes back to her stool to practice the mating ritual of the middle-aged woman: When there’s a game on, Tanya mimics the guys’ excitement and disappointment until one of them says something like “You saw that. He was safe, right?” And she agrees, and maybe she gets a free drink. Maybe more. She is convinced that the way to a man’s heart is by rooting for his favorite team. Randy’s not really into sports. Sure, he’ll watch a game, but he doesn’t date cheerleaders anymore.

I whisper to Randy that I hate Tanya, and he tells me to be nice. We take two seats at the end of the bar and toast to my new job. Randy’s not a bad guy. It’s just hard to love someone you find unexciting. Or maybe it’s just hard to love someone.

Randy’s got two roommates and no plans to move out. His buddies are not my buddies. Our relationship has a lot to do with convenience. We’re both still in this small town. My parents like him all right — not that it matters the way it used to — and I like him all right. He reaches for my hand. His is warm and moist. I order another drink and hold his hand longer than I want.

“I should go,” I tell him.

“You’re not driving, are you?” he asks.

“No. I walked.”

“Well, text me when you get home so I know you’re OK.”

Some nights I think Randy will leave the bar when I do, but this seldom happens. At least he walks me to the door. It’s raining outside. Randy leans me back, and we kiss like movie stars. His mustache tickles. Then he sees the rain and tells me I should put my hood up. My coat doesn’t have a hood. He doesn’t offer to drive me, and I don’t ask.

On the walk home I hear thunder. It’s like the sky is growling at me. The walk is sobering. Within ten minutes I’m home, drenched.

My mother says I’m dripping everywhere — and why didn’t that boyfriend of mine drive me home?

“How did the refinancing go?” I ask.

“Your father still thinks we can get a better interest rate.”

He laughs and says, “I told the guy I just couldn’t do business with an ugly-bear-statue kind of bank.”

“Thanks, Dad,” I say.

I’m not part of their Florida plan. I’m not part of anyone’s plan. My mom says it will be at least a year before the house is on the market. She takes a phone call. It’s my brother. She tells us he and his wife are going to bring the kids by next weekend. Then she goes into another room to talk to him.

My father pulls out his lottery ticket. “I was waiting for you to check the numbers,” he says. He missed the live drawing: that guy from the bank sure was a talker. My father hands me the ticket and tells me to look it up online. “Wait,” he says. He makes his way over to the recliner. He sits down and leans it back. Then he closes his eyes. “OK, I’m ready.”