The train in South Tyrol loads up automobiles like cargo, their passengers buckled inside, preparing to pass through the tunnel to the other side of the mountain.

“It’s the quickest and easiest way to cross,” her lover says. “Driving all the way around takes ages.”

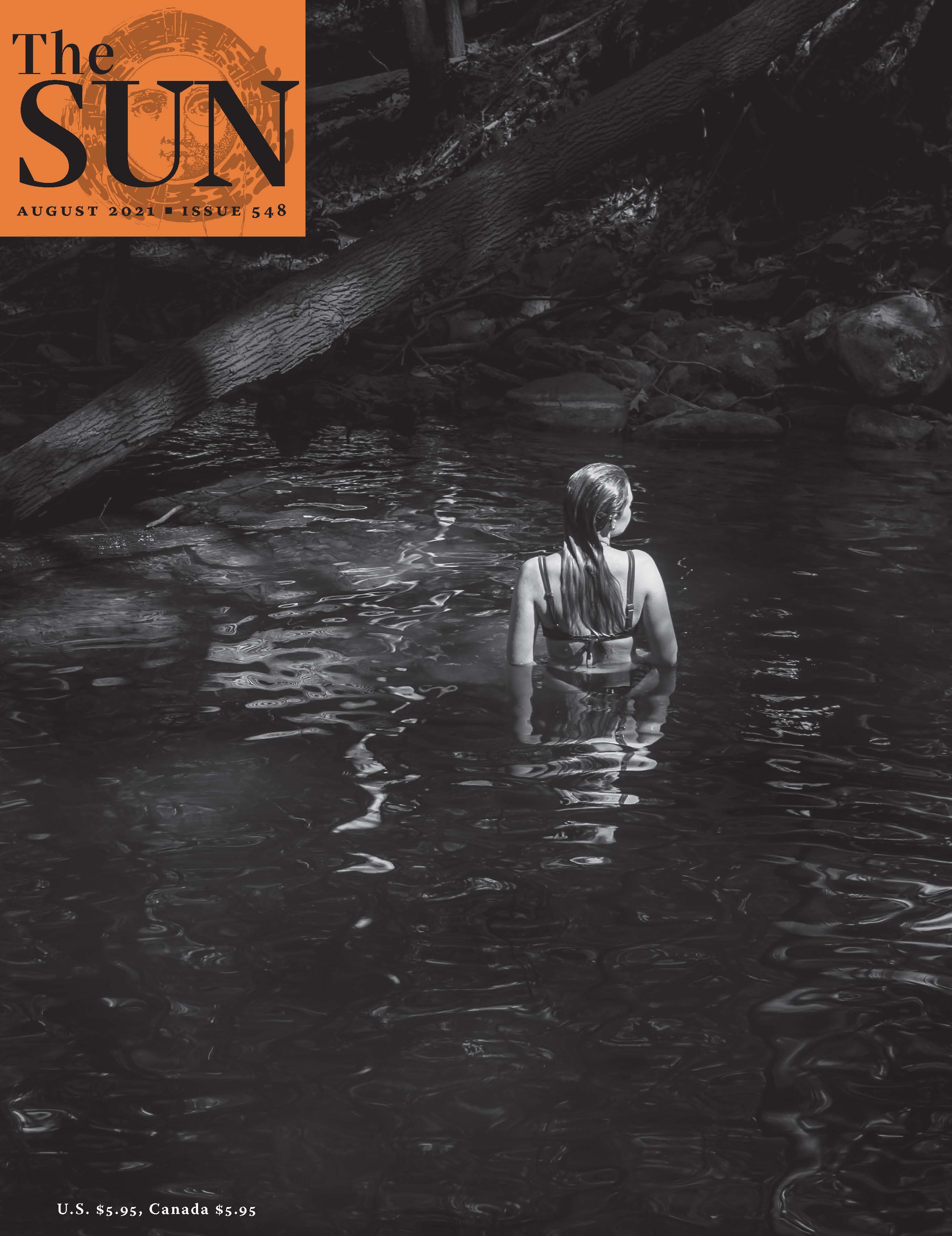

She welcomes this adventure the way she’s welcomed every new thing they’ve done in the last three days: eating colt steak and wild boar; drinking orange wine and schnapps that made her eyes burn; having sex in the loft of his hilltop cabin; stumbling out of the sauna to sit naked by the fire, the moon trailing pale light across the forest surrounding them.

The train — really a raft of steel with vehicles balanced on top — is like something from a modern fairy tale. She’s never been to this part of Europe before: near the border between Italy and Austria, the signs in both German and Italian. Before leaving the U.S. she tried to find it on a plastic globe at World Market, where she’d been sent by the daughter of a dying man to buy a bar of his favorite chocolate: extra dark with a cherry pressed into each cube. She did this a lot as a hospice nurse: fulfilling someone’s dying wish — for a song, a hug, a chocolate bar.

Her lover checks the train schedule in the one-room station; then they get in their car and drink from a flask filled with Scotch whisky that she bought at the London airport. She arrived there three hours early for her flight, afraid she wouldn’t go through with this, and now here she is doing it. She feels so much like herself that she realizes the self she played at being back home in Oregon with her husband will have to be abandoned, no matter what happens. That is OK. She understands that she is still a middle-aged woman (forty last month), still a hospice nurse who will be expected, upon her return, to be helpful and kind. She will still have to practice her smile as she drives to work — literally practice it, staring in the rearview mirror at a red light until her mouth shifts from a grimace to the soft smile of a woman who helps people die. For fifteen years she’s been practicing that smile, doing this work. With grace and dignity, they promise the dying people and their families who come to them requesting help. Grace and dignity. A necessary and ultimately forgivable lie. She’s seen so little of both.

“It’s like I am the tragedy-comedy mask,” a male nurse said during the weekly mandated therapy session to combat burnout. She was burned out by the therapy sessions but had found ways to cope. The other nurses, mostly women, looked catatonic or desperate for one of the martinis they often drank afterward at the bar next door. “Now, this is helpful,” they would agree, clinking their glasses. If someone started to cry (always one of the new people), she placed a mask of sympathy on her face and pretended to scratch her ear, turning up the volume on the James Joyce short story she was listening to through a single earbud hidden behind her hair. She felt like a spy or a bodyguard, adjusting her earpiece. Lily, the caretaker’s daughter, was literally run off her feet, said the deep-voiced narrator into her right ear as she directed a sympathetic gaze toward the crying man. God, she hated therapy. But she loves Joyce, especially his short story “The Dead” — which sounds too expected, given her profession, but her connection to the story is real, even more so now, as Joyce is what led her to her lover, who is from this border place in Europe that is both/and, not either/or. “Joyce was blind at the end of his life,” her lover told her once, when they were still just online friends.

The sky is darkening. The air is Alpine cold and smells like a ski holiday. Last night her lover stretched his long legs across her lap, but not before asking first, “Is this OK?” as if he might hurt her. She spread her palms across his thighs and said, “You can’t break me,” which of course wasn’t true.

His legs were heavy and healthy. Bodies: so astonishing, so mortal, so doomed.

At home in her dumpy Oregon beach town, her husband is not yet thirty and already growing a paunch. He never gets up before 11 AM and is always despondent. He tells their friends he is “independently employed,” but he has no savings, no job, and no prospects. She supports him through her labor with the dying, her long hours and overtime shifts. He was a musician when they met: floppy-haired, hip, successful, about to break through. She’d been so grateful for his lithe body, his baritone voice, and his attention to her, with her average build, average face, thick ankles, and sad job. But the band never got a break or a record deal, and the members were now “in diaspora,” as he called it, which meant that they would never make any money. He has not wanted to have sex in more than a year, though at the beginning of the relationship she could hardly keep up. The last time she asked him for it, he refused, and she understood that this was how it would be now. Later that night she went to her desk and e-mailed this man in the mountains between Italy and Austria and said, “I’d like another life.” What he wrote back — “I’d like a chance at some time with you” — was unexpected but exactly, she realized, what she had most wanted to hear.

She smiles at him now, and he looks at her the way an animal might, with an expression on the delicate border between trust and wariness. “Open your eyes,” he says when they have sex. Her husband only ever wanted her with eyes closed, as if they were two strangers locked in the sticky cinemas of their own fantasies and not married people supposedly in love. She wonders if she will once again be made a fool in this relationship, but she feels for her lover every feeling she’s ever wanted to feel for or about anyone, so at the moment she doesn’t care. If dying with dignity was impossible, so much more so was falling in love.

They’ve known each other for three years, but this is only the second time she and her lover have met, and the first time they’ve touched. She wanted to touch him the minute she saw him waiting for her at the train platform in Berlin, where they’d both signed up for some silly academic conference — “The Role of Death in Literature.” They’d agreed to meet and see. See what? See about this, apparently. He is writing a book about Finnegans Wake and Moby-Dick. (“Both?” she marveled when he told her.) She is a death nurse. They met online in a chat group about Joyce’s work. At first they did talk about books — in those group chats and then over e-mail and finally over the phone. They still do. They also spend a lot of time reading. Sometimes she reads to him at his request, and she thinks she could do this forever: in outdoor cafes where she doesn’t stop even when the church bells chime; wearing a headlamp in the cabin at night, reading to the story’s end after he falls asleep; in the car waiting for his clothes to get clean at the laundry, the sun stretched over them like an afternoon nap. “I like your voice,” he says. This surprises her. Hers is the voice people never want to hear again after someone they loved — or maybe hated but pretended to love — has died and been hauled out of the house in a bag. And now here is this man saying, “Read to me.”

She’s been trained to minimize pain using a veneer of mild happiness. Her lover, on the other hand, doesn’t smile a lot. “Is it a German thing?” she asked. “I’m not German,” he said, unamused, but she has come to love his stoicism. When he does laugh or sing — and especially when he comes, his breath hot in her ear — she is witness to something special that she has drawn out of him, like a talent or a lie.

Two days ago, following an afternoon spent walking around nursing hangovers, he started singing in the car, and, even though it was cold out, she let the window down to release the sound as though holding it inside an economy-sized Kia were a crime.

A group of people hover around a cooler in the back of another car, also waiting to be hitched to the train and spirited underground. One of them puts on a pair of thin gloves, although it’s not that cold.

“Do you think they’re Americans?” she asks him, passing the flask. His nails are clean, but he knows how to work with his hands. He helped his father build the small cabin where he now lives, the place where they sleep and fuck and roll around; a cabin heated by a woodstove, where the bed is a mattress on the floor of the loft and the refrigerator is outside: a sort of cave cut into the mountain to hold milk and cheese and slabs of meat. Once, in the morning, she looked out the window and saw a family helping themselves to some food. He laughed at her alarm. “I leave it unlocked,” he said. “Anyone can take what they like, sit down, have a picnic.”

She feels beautiful, a rare feeling, and she wonders if her husband will say he wants her back, the way he has before when she’s threatened to leave him. It’s probably true he doesn’t want her to leave, but it has nothing to do with love. She is no longer a thing to be kept by anyone, ever again. How glorious. It’s making her cry, this feeling of freedom. Or maybe it’s the whisky.

“Australians, I think,” her lover says. There are three of them, lifting triangles of cheese from a wheel, sharing a bottle of wine among them.

“They’re tailgating.”

“What’s that?” He lifts the flask carefully to his mouth.

“It’s when you drive your big car into a parking lot before a college football game or a concert, and you drink beer and eat chicken wings and get high.”

“Is it fun?”

“Not really.” Her memories of tailgating as a teenager usually end with shoving a swaying drunk away from her (once it was a friend’s lecherous father) or being fingered under the bleachers by a guy from the Catholic high school who promised to call her the next day but never did.

He shakes the empty flask and says, “All done.” She takes it from him and tucks it under the seat.

In bed her lover plays her like an instrument, with more finesse than her husband, an actual musician. It doesn’t feel like How long will this take? She doesn’t have to pretend. It feels necessary and easy and sweet as he bites down gently on her shoulder.

These Australians, if that’s what they are, seem pensive and contained. She’s embarrassed by the Americans they’ve seen, with their trashy tailgate traditions, their barking voices, their love handles, their bright-white sneakers, their tendency to announce whatever they see or are about to do: “Look at that sunset!” “I have to pee!” She hates their entitlement, how they encroach on your experiences, offering observations that anyone could easily make. She wishes Americans everywhere would just shut the fuck up.

She longs to reach over and hold a part of her lover: a finger, a knee, his neck — not for the affirmation that might come when he touches her back but because he is extraordinary. It’s as if she’s been locked overnight in a museum and has found a statue she likes best among the gods and goddesses with their bows and arrows and lightning bolts, and this one — all stone curves and cock and flowing hair and arms and stillness and calm — is the one she wants to touch, to seal its shape into her muscle memory the way she remembers how her arms lift a palsied body from the bath; how she touches the forearm of a grieving son just so; the way she tents a tissue from the box with her fingers and passes it to a person during the first end-of-life-care discussion.

She knows well how to calculate the moment when people are likely to die, but she has forgotten, until now, how to tell when someone is, in fact, living. The first hour she was with her lover she sobbed into his shoulder while he held her, saying, “Shhh,” stroking her back. “We really can just keep talking about Joyce,” he offered, which made her laugh and then cry again. She had grown so distanced from desire that she could initially feel only uncertainty and deep embarrassment that she was putting herself at risk, like a deer crossing the road. Perhaps she was being ridiculous, but there were worse things to be. Like dead.

She decided to visit her lover the day after caring for a very small boy with a rare, ridiculously cruel illness that would deliver him into a vegetative state in a matter of months: a mistake in the mitochondria, a wrenching condition he’d lived with for nearly two years. The prognosis was grim and wholly unstoppable. Oxygen machines, lung pumps, seizures, bedsores — he had all of it, and the most loving mother, so attentive, so knowledgeable, so full of meritless hope. The hospice nurse had no children of her own, and she wondered: Was she the right person to see this child through to the end? But she had “caught the case,” as the other nurses said, as if they were homicide detectives. Though clearly grieving, the mother said, “Isn’t he beautiful?” He was, but what was even more beautiful — and terrible — was the love on the mother’s face.

The nurse knew what to do: be calm, be professional, don’t react, don’t freak out. She did all of this. She explained the care plan. Decisions were made, documented, carefully reviewed. She told the boy’s mother to post the “Do Not Resuscitate” order in their front window: “Use industrial tape so it can’t fall off.” She emphasized this, because if the sign fell off, then the medics, when they arrived, would pump the boy’s chest for up to half an hour, and this would be unbearable to the mother. She told the mother she’d be with her every step of the way. She wondered where the hell the father was, but of course she didn’t ask. She summoned the doctor, stepped into the hallway, and vomited into her hands.

Even after she washed up, she couldn’t swallow the sob stuck at the back of her throat. Her face was as hot as when she’d once fallen asleep in a tanning bed, before people went bananas about the “life-limiting” danger of UV rays. Such a stupid phrase. Everyone’s life is limited. Through the glass window she saw the mother signing papers, the doctor’s hand touching the mother’s briefly, then checking the pager at his waist. The world of the dying is a busy place. This mother was entirely alone in it.

I want to come and visit you, she texted her lover, who was then just her friend, fumbling with her phone as if she’d witnessed an accident and was calling it in.

When? he texted back immediately.

She told her husband, “We’re through,” moved into the guest bedroom, and booked a ticket for three months out.

Her lover is quiet as they wait for their car to board the train. “You OK?” she asks him now. Such an annoying question; she feels foolish for asking it. The Australians are quietly packing up. One of them laughs, pats another’s back.

“I am OK,” he responds evenly. He doesn’t sound annoyed. In fact, he seems happy to have been asked.

It was two in the morning, and the moonlight flashed from the waves along the sad strip of beach outside the hotel where the nurse was staying, when the mother called because her son had suddenly stirred, made a sound, and sat up. “He made a sound!” she said. “He doesn’t make sounds! He doesn’t sit up!” The nurse got in her car and drove along the streets near the beach, which at this hour were heaped with garbage bags. Her arrival at the mother’s house would mean the end of the son’s story, not the beginning.

The mother flipped through the book frantically, medicine bottles lined up on the kitchen table beside her, her red nail polish chipped, her forehead sweaty. “What does it mean, ‘surge of life’?” the mother asked. “I looked it up in the book you gave me.” (The “death playbook,” as the nurses called it among themselves.) The father was sitting at his computer (paying bills? playing video games? looking at porn?), a dark hoodie pulled up over his head. The nurse had only ever seen him in profile. Silver moonlight fell through a window in the room where the dying boy lay. “He’s resting now,” the mother said about her son, “but I thought, I thought maybe . . .” She pointed to “surge of life,” underlined in the book. The mother hadn’t read the full description, only the “life” part.

The nurse’s heart felt hollow. “We’re still near the end,” she said softly.

The mother nodded and closed the book. No miracle, no answered prayer.

Just then the pulse oximeter attached to the little boy’s toe sounded its final warning, and the mother jolted as if awakening from a bad dream. Of course she would remain in this nightmare long after her son’s malformed heart and compromised organs had finally given out, which they did seconds later. The silver light through the window was unchanged, and yet everything had changed. The father appeared at the final moment, a ghost in the doorway. She placed her hand on the mother’s back, hunched over her child. A miserable, whistling sound came from the mother’s closed mouth, like the lowest note a reed instrument can make, a sound that said, Come back.

Now the conductor motions for them to drive their cars onto the platform. Her lover shifts in the driver’s seat, his legs so long his knees touch the steering wheel. Once they’re in position, he puts the car in Park and turns off the ignition, and they watch as the wheels are secured with a series of chains, which the conductor yanks on three times with his gloved hands. The car bounces slightly, shifts from side to side a bit. It’s clearly tethered — she can see the thick metal looped around the wheels — and yet the hold feels tenuous.

The conductor salutes them as the train pulls into the mouth of the tunnel, and they begin to rock back and forth on the platform like a loose tooth. They move through the darkness.

“The only way out is through,” she says probably a hundred times a week to bereaved people about the process of grief, which of course is not a process but a hurricane, a tornado, a tsunami — name your disaster. There is no single way to bear it. There are too many ways, just as there are too many ways to die. Her lover knows this well. He survived an earthquake, a massive one, and when the earth stopped bucking, he looked around, and people were piled all around him, dead, and he was not. He survived a car crash that broke both of his legs, an avalanche on a hiking trip as a teenager. He is sinking lower in his seat, as if by becoming smaller he might become more difficult to harm. But she knows that nobody can ever be small enough to avoid dying.

“The sound is too much like an earthquake,” he shouts at her, because it’s so loud inside the tunnel. She unbuckles her seat belt, maneuvers herself across the stick shift, and lays her head on his chest. “A lot like an earthquake,” he says again, into her ear, like the deep, rumbling voice of the narrator on her Joyce audiobook. She wraps her arms around his waist, presses her lips to his heart, and feels it beating. She won’t ask, Are you afraid? because she can feel it in his body, the reliving of a moment when the earth was not what the earth was supposed to be: solid, unwavering, safe.

This is their last day together. Of course, it could always be anyone’s last day. Perhaps that is the truest expression of love: living with the knowledge that all can be lost at any moment, the many moments collapsing into the single final moment, and thinking, Perhaps it’s enough.

She’s spent the last three years chatting with her lover online, telling him about her life: about how some of her patients are so difficult and nasty that she doesn’t feel sad when they finally die, and then she’s flattened by guilt for days; about how she sometimes mixes up the charts and ends up with Mr. Smith’s chart in Ms. Beckett’s room; about the living funeral one of her patients held so that everyone who had ever loved her could say goodbye before she entered the final morphine haze; about how hard it is to get doctors to give up on young people’s bodies, even if the thirty-two-year-old has the heart of a ninety-five-year-old, even if the teenager has a liver that has to be drained of fluid every fifteen minutes. If you’re young enough, people want to believe that you can fight your way back.

“I can’t hear about your dying people anymore,” her husband told her soon after they were married, although he’d been happy to listen when they were dating. “It makes me more depressed than I already am.”

But her lover knows about the little boy who died, and he asked her about him yesterday as they were wandering a village. They walked along the cobblestones, past unsmiling vendors selling chestnuts from shabby stands plastered with ads for restaurants and nightclubs. The air was still and warm, though chilly in the shade. She didn’t like to talk about the little boy, but she liked to be asked about him all the same. “I’m OK about it,” she lied as they passed a ruined building. Fake it till you make it, they used to say in nursing school when it was someone’s first time doing something with a needle or a tube or another device that could quickly become an instrument of torture.

“I love me a ruin,” she said cheerfully, stepping across the crumbling threshold to hobble around a pile of rocks that had once been a building. A three-legged table was marooned in one corner, as if growing out of the wall. Rusted nails in the ceiling were hung with cobwebs. Light trickled between the gray stones and turned the mess into a possibility. “It could be a nice space,” she declared, and she meant it. This was what it was like to do the work she did, to recognize the person in the dying body and to stay with them — like bearing witness to light moving through wreckage, stubborn and pure. This was also, she thought, what it was like to keep living. But she hadn’t realized it until the death of the little boy, until this trip, until her lover, who throws her off balance in a way that makes her feel safe.

As the train moves through the deepest part of the mountain, the engine’s lights cut long, narrow holes in front of them. She lifts her head from her lover’s chest, sits up, and rests a hand on his shoulder. He is a thinker; he likes to think. It can be hard to do that when someone is stretched across your stomach, blinking up at you while a World War II–era train rattles your bones. Instead she looks out the window into the black tunnel and tries to find the line of rail they are traveling along but cannot.

She thinks about the last patient who died in her care before she left Oregon, where the Death with Dignity Act had been passed, though none of her patients seemed interested. He was an old man dying slowly of liver cancer, unpleasant and irascible, and nobody ever came to visit him at the hospice facility. He didn’t like her perfume; he didn’t like her clothes; her voice was “too chirpy.”

She smiled and carried on as she’d been taught to do. “OK now,” she said as he voiced his various discontents. “OK now.”

As he neared the end, she asked him if there was anyone she could call, and he said, “Everyone is dead.” She changed his bedding, his tubes, his rancid bedpan. She carefully washed his face and hands, his body so shrunken that the small cross he wore around his neck resembled the prow of a ship pinned to his collarbone. She pumped medication into his line, then clear fluids for hydration, then just morphine. He lay wilting and miserable and yellowing for weeks. (Patients with liver failure always made her think of very old newspapers.) And then, one day when she walked in, he was sitting up, fully alert and looking alarmed. “I have something to tell you,” he said. “I’ve never told anyone the truth about who I am.”

His name wasn’t his real name, he said. The parents who’d raised him weren’t his real parents. And he wasn’t a Christian. He spoke clearly and calmly in a voice like a reporter’s, and she realized she’d never asked what he’d done for a living before he was reduced to complaining about her floral culottes and Prada perfume. He’d never believed in Jesus, he said. He’d been pretending all his life. He’d married a Christian woman, divorced her, and married another, a Baptist this time. Then she’d died. No kids. “This is what happened.”

He was on a train from Germany to Poland. A cattle car. (She pictured Eastern Europe; the panicked people spilling out, gripping their hastily packed, pointless suitcases; the whistles and pluming smoke in the dark; the puking and the shitting and the fingers waving desperately between bars and the screaming.) He was four, but he had the scrawny, malnourished body of a much younger boy. For hours he watched his parents hack away at the wooden floor of the train, where the planks had warped enough to pull apart. “I thought we were all getting out, and I was happy.” Perhaps this was his first memory, watching his parents sweating and crying and ripping their hands until blood outlined the ragged hole. Then, in the middle of the night or early in the morning — nobody had any sense of time — as the train was slowing slightly, his mother gripped him by his shoulders and said, “You must go now.” He didn’t want to go. “I begged her. I said, ‘I won’t go. You have to come with me.’ ”

The man’s voice wavered. The nurse swallowed and said, “I’m listening. I’m here. Go on.”

The hole was big enough only for the smallest of bodies, he explained. These parents — the bravery of them! the strength! — pushed him out of the moving train, not knowing if he would live or die, only that if he stayed on the train, it was certain death. “I broke both my legs,” he told her. “And my wrist.” He lifted his right arm a few inches off the mattress. It looked just like the other one, stick thin and easily breakable, kindling for the fire. He set the arm back down, and she rested her hand on it. “I managed to crawl into a field, and a Christian farmer found me and took me in and raised me as his son. He became my father, and I loved him.” His eyes were wet, but no tears fell. “I never saw my parents again. I can’t remember their faces, only their backs as they hunched over, digging the hole all night. I have no photographs.”

He rested back on his pillow, closed his eyes, and died soon after.

Her mother was Jewish, but it wasn’t until her grandmother’s funeral years ago that she’d first heard the Kaddish. The hospital had a chaplain who was a rabbi, and she walked to his office and asked if he had a copy of the prayer she might borrow. “Do you want me to read it?” he asked after she explained the situation, rising from his chair. “No, I’ll do it,” she said with a force that surprised her, but she did ask for help with the Aramaic, which felt like wrapping your tongue around loose ball bearings and trying not to let any of them fall from your mouth or roll down your throat.

She repeated the Kaddish three times in the rabbi’s office, and then she said it, slowly and awkwardly, over the man’s dead body before they took him away. She left the cross around his neck. He’d probably worn it all his life.

She wants to tell her lover this story now, but instead she thinks of how he touched her sweating back in the sauna, a finger tracing her dripping spine, and later they sat beside the fire outside. In the dark woods bears rooted around in the shadows of trees, not far from the circle of light.

It was so strange to know someone at the end of their life, at the end of worry and alarm and desire and danger and decisions and hope; to release them into the unknown with a push from a train, with the plunge of a syringe, with a refusal to pump their chest up and down and breathe forcefully into their mouth at prescribed intervals. It was just as strange, and also terrifying and beautiful, to know yourself at the beginning of something new, a moment that marks the death of who you once were, which is one way to describe falling in love. To help a stranger die was not so different from realizing the person next to you might have died, and will die, as will you. But likely not today.

When the tunnel releases them and they emerge into a night that now seems unnaturally bright, it’s like flying into a net of stars; like being found in a field, pulled back from the lip of every possible ruin.