Browse Topics

Altered States

The Good Red Road

Leslie Gray On Rediscovering America’s Oldest Psychology

When I used to teach Native American studies at Berkeley, I would offer an A to any student who could come up with a Western model of health. No one was ever able to do it. The West developed only a model of disease. Therefore all of its treatments are based on a negative model. They are all “anti”: antidepressants, antipsychotics, antihistamines, antibiotics, and so on. And we are constantly being told that we have to “fight” this or that illness. This is a dualistic way to look at healing. The Native American model is a model of health. It is about the restoration of balance to body, mind, and heart. It assumes that we sometimes go out of balance, and good health depends on restoring that balance.

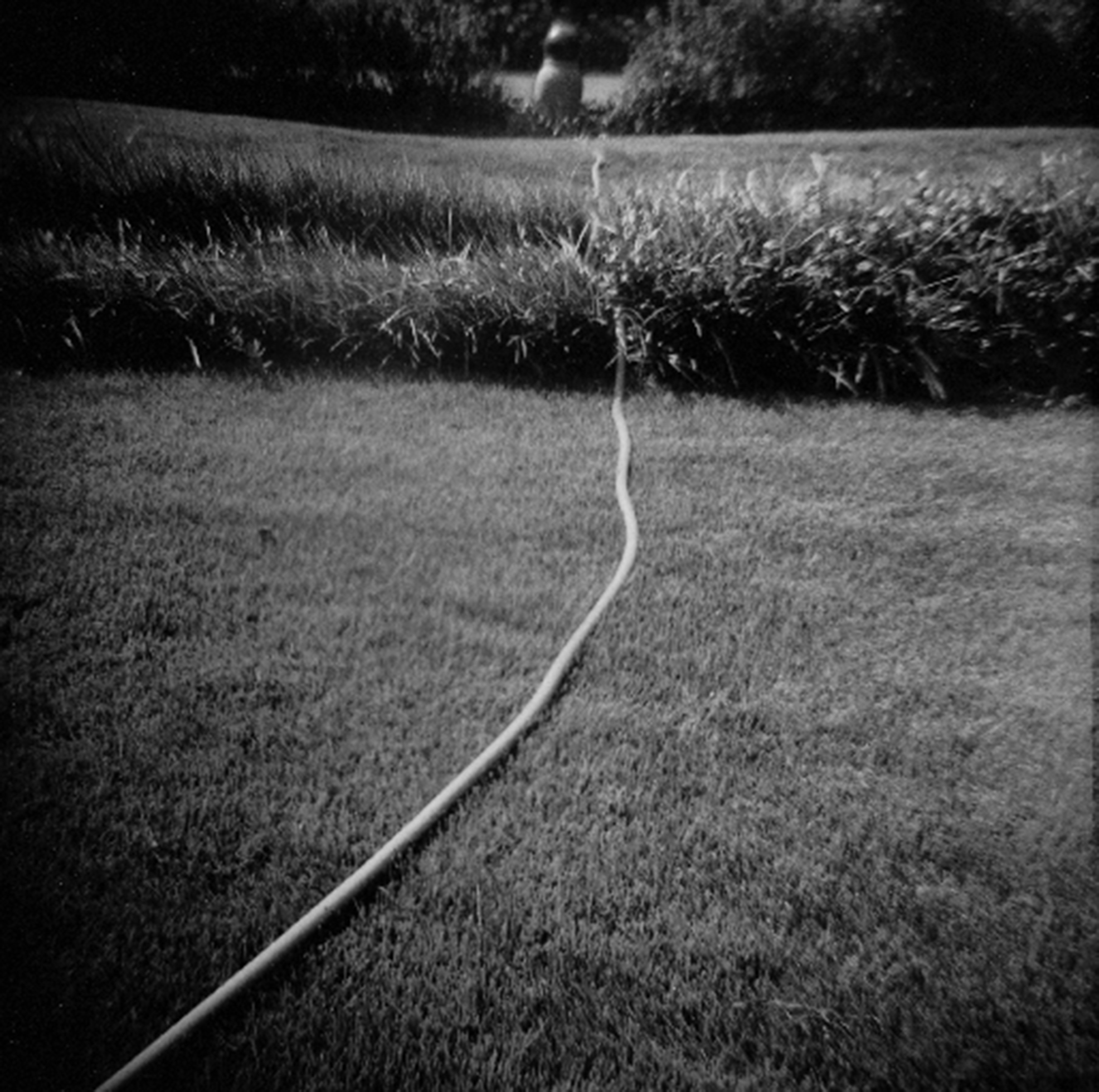

April 2009Mrs. Bernadette

Once, Mrs. Bernadette described the effect to me: “Have you ever seen a crow in flight, and you saw its feet pulled up under it as it rowed itself to wherever it was going? When I get the laughing gas, I feel like those helpless feet being carried along underneath that beautiful bird. It’s nice to let something else take over for a while. The world is too much with us.”

September 2008Ponchatoula

I was twenty-one years old and taking freshman composition, because I’d gotten a late start in college. I probably wouldn’t have gone to college at all if I hadn’t lost my left arm in a car accident at the age of nineteen.

August 2008The Madness Equation

When your child goes mad, you begin to question everything you once thought to be true. Even if you’ve been a questioning person all your life, as I have, the things you took for granted — or, as my college English students often write, “for granite” — no longer lie rock-hard in your palm, but shift and slip away like sand.

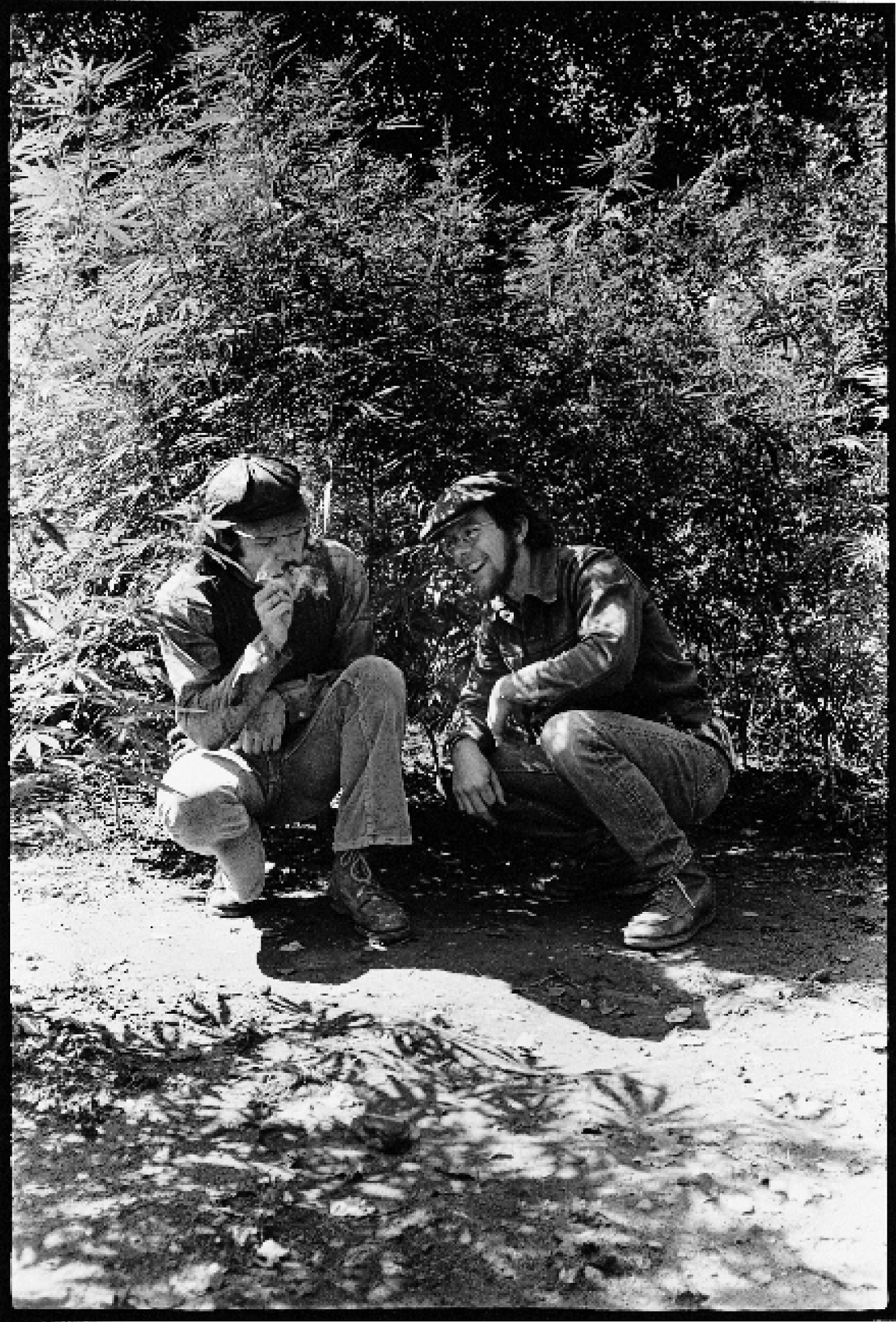

September 2006Marijuana

Two tightly saran-wrapped joints for Grandma, a baggie on the water fountain, Desi Arnaz

May 2003Tricks Of The Trade

Alfred McCoy On How The CIA Got Involved In Global Drug Trafficking

We’ll never know what might have transpired if Western intelligence agencies hadn’t used the power of the underground drug economy and its criminal syndicates to fight communism during the Cold War. If the CIA hadn’t existed, would we have the levels of addiction we see today? I can’t say. But I can say that covert operations played a significant role in the expansion of drug trafficking after World War II.

May 2003The Botany Of Desire

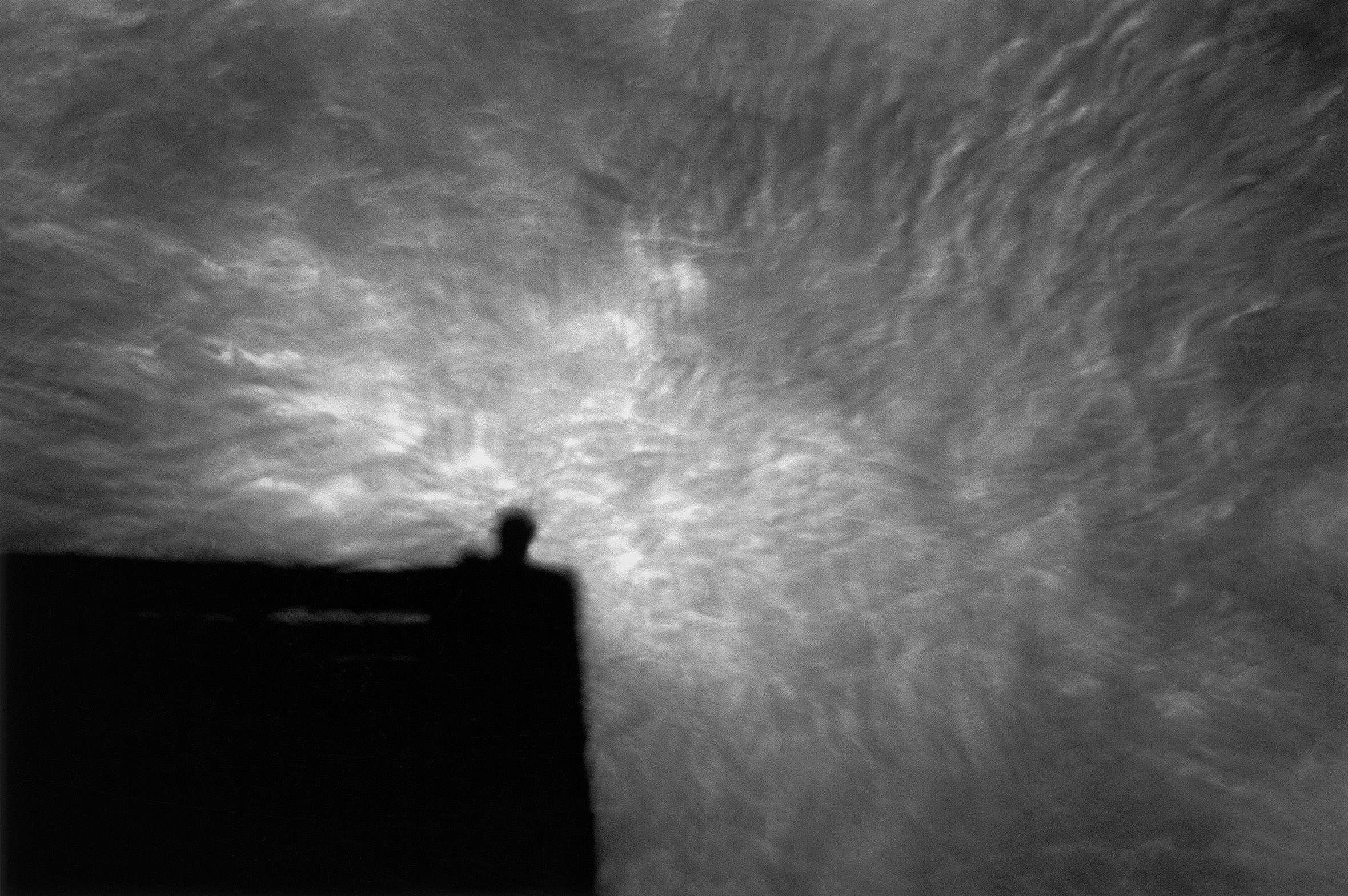

Memory is the enemy of wonder, which abides nowhere else but in the present. This is why, unless you are a child, wonder depends on forgetting — on a process, that is, of subtraction. Ordinarily we think of drug experiences as additive. It’s often said that drugs “distort” normal perceptions and augment the data of the senses (adding hallucinations, say), but it may be that the very opposite is true — that they work by subtracting some of the filters that consciousness normally interposes between us and the world.

May 2003Stigmata

I can’t dismiss religion and the girl with the stigmata with a sweep of my hand, for I feel a soul pushing at the walls of my breast. I believe in enlightenment and that our paths are divine. There’s no proof of it, but energy descends on me, and I feel like one raindrop amid thousands, all refracting light.

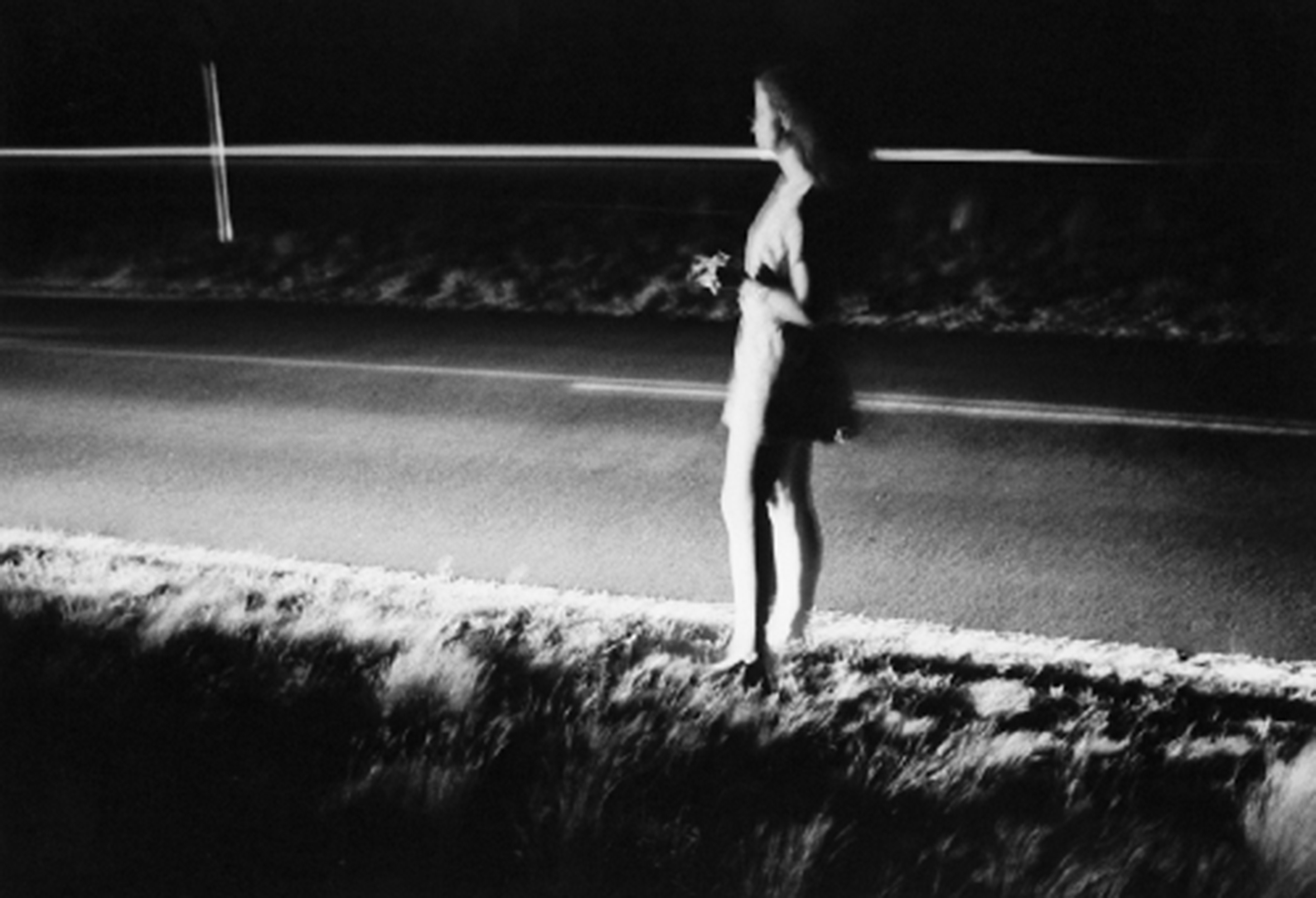

August 2002Ecstasy

I suppose it might make sense at this point in my life — with a wife and a son and long afternoons of contentment drawn around me — to disavow my passion for Solange. Or, at the very least, to relinquish her memory. But you don’t relinquish anything when you’ve fallen in love, no matter how briefly. The heart writes in indelible ink.

June 2001