When I showed him the button, Andrzej squinted at it through a magnifying glass. We stood on a fallow wheat field, our metal detectors resting on the soft earth, near a village called Suchy Dąb on the north coast of Poland. It was winter, but there was no snow. The air was fresh and cold. After a first look, Andrzej spat on the button, rubbed it with his glove, and looked again.

We had been searching for hours. We’d gotten up early that morning, at the home he shared with my partner Ewelina’s mother, and we’d driven twenty miles to a rural farming district where Andrzej thought we might find silver coins. It had been the site of many battles, he said. The Crusaders had fought on this land. Then Polish feudal lords had struggled over the territory. Later came Napoleon on his way to Russia and, finally, the two World Wars. All that violence had left remains in the soil. Andrzej and I were there to dig them up.

The button was rounded on one side and flat on the other. There was a shred of leather on it and a faint pattern. Andrzej, who was in his early sixties, had spent the last four decades doing the quiet, often solitary work of metal detecting, swinging the detector — a four-foot rod with a coil at the bottom — left and right, listening for beeps. It was more than a hobby for him; it was his business, his livelihood. He sold detectors and also the items he unearthed. (A single coin had once bought him a car.) A room in his home was filled with recent finds — Nazi belt buckles, Soviet medals, Polish buttons, coins from hundreds of years ago, gold rings, cannonballs. Another room held buckets of shrapnel and mangled bullet casings that Andrzej sold as scrap metal. He’d found entire rifles, unexploded ordnance. Once, he told me, he’d uncovered the remains of a Red Army solider. He’d fashioned a wooden cross, placed it on the ribs that jutted out of the earth, and reburied the bones.

Poland’s forests are home to trenches, earthen fortifications, foxholes, bomb craters — the scars of a country that many have seen as a prize to be won, a land to be conquered. On an earlier trip Andrzej had shown me a World War I trench cut deep through a forest and, not far from that, German and Russian foxholes from the Second World War. I’d lain on my stomach in one and peeked over the lip. I could almost see enemy soldiers, rifles raised, charging at me or shuffling through the trees. We found dozens of buried bullets, and Andrzej found a silver two-mark coin with a swastika on it. He knew where every battle had been fought, by whom, the kind of guns they’d fired, the coins they’d carried, the buttons they’d worn.

But my button was unusual. Andrzej stared at it, turning it in his fingers to examine its markings. He handed it back and said that it could be from a Hitler Youth uniform — “either from the shirt or maybe from a satchel.”

The little button lying in my hand brought the violent history of the place to life. For a moment war wasn’t just pictures in textbooks. I could feel the residue of it, the half-life of violence. Holding the button and looking out at the gentle hills of dark-brown earth, the cinder-block farmhouses with smoke rising from their chimneys, the gray dome of the sky above us, I felt something well up in me — something ineffable.

I ’d followed Ewelina to her native Poland in early 2013, and we’d found a place to live in Warsaw. On a main thoroughfare there was a cafe where I liked to sit in a large armchair and read. The chair faced a window with a view of the high-rise Palace of Culture and Science, Stalin’s gift to Warsaw during the Soviet 1950s, which dominated the skyline. I was reading a lot of atheist authors at the time: Christopher Hitchens, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, and Richard Dawkins, who argued that religion was not just illogical but poisonous. The godless world that Hitchens, in particular, proposed made sense to me. His takedown of monotheism, though pompous, drew me in. The institution of religion had never made much sense to me, even as a child. Now I denounced it as an age-old anachronism to be shaken off. It seemed to me that those with deep religious belief needed God simply because they couldn’t handle the complexity and cruelty of the world. They couldn’t handle life.

Ewelina seemed unsettled by what I was reading. Though I never knew her to pray or go to church, Catholicism is in the marrow of her bones, a part of her identity, as it is for most Poles. Almost without exception, schools, hospitals, and government offices in Poland have at least one crucifix on the wall, and often a picture of Christ under which is written, Jesus, I trust you.

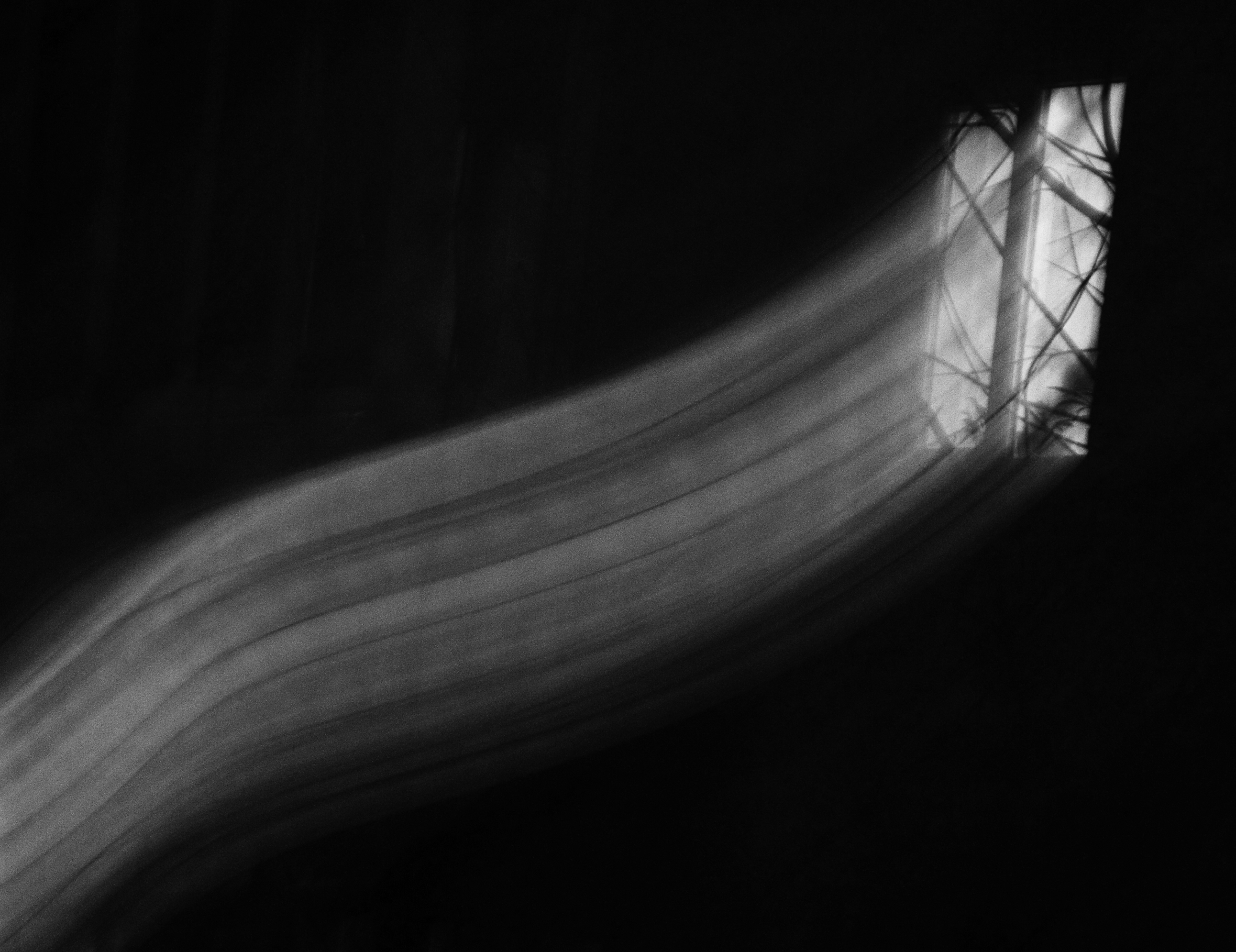

The night after I found the button, I woke from sleep with a rumbling in my chest. It felt like little stones were jumping around in my lungs as I breathed. I lay in bed and watched the pine trees outside sway in the moonlight.

The next morning I went with Ewelina to town to see a doctor, a grouchy, balding man with a bushy white mustache who spoke no English. I sat shirtless on his wooden examining table, breathing in and out, the cold metal of his stethoscope pressed against my chest. He said something in Polish.

“He’s asking whether you’ve been outdoors lately, in the cold,” Ewelina said.

I had her explain that I’d been metal detecting in the fields. The doctor nodded, then scribbled several prescriptions and showed us out.

“He says you have bronchitis,” Ewelina said in the wood-paneled hallway. “It’s because of the cold. He prescribed antibiotics.”

We stopped at a pharmacy to fill the prescriptions, then took a bus back to her mother and Andrzej’s place. It was a dreary, wet day. The sky was dark and heavy with rain.

I took the pills with sweetened tea, but the rumbling in my chest didn’t go away that night, or the next. After my fourth night of sickness, I sat at the table with Ewelina, her mother, and her sister, eating a Polish breakfast of rye bread, cheese, ham, butter, tomatoes, and green onions. I mentioned the button, the strangeness I’d felt when I’d held it up to the light and examined it.

Ewelina’s mother looked at me and said, “That button’s bad luck.”

The next day, feeling no better, I went to another doctor, who was as gruff as the first. I received another exam, the same diagnosis — bronchitis — and a supplemental dose of antibiotics.

Again that night I lay awake listening to the rumbling in my chest and to Ewelina’s clear breathing beside me. I began to worry. Why weren’t the antibiotics working? What did I really have? It was snowing outside. Frustrated and afraid, I got up and went to the windowsill where I had put everything I had found with the metal detector: A Polish Army button, the size of a quarter, with an eagle on it. Some Russian shell casings. A two-pfennig piece from Prussia dated 1844. (I was really proud of this.) A little chunk of iron with the word Danzig stamped on it — a balance weight from an old scale. And the button. I picked it up and held it in the crease of my palm, the way I had when I’d found it. In desperation I walked out the door, went down the stairs, strode into the forest behind the house, and buried it. I went back inside, my hair dusted with snow, and returned to bed, certain I would recover now that the sad little button no longer sat on the windowsill.

But by morning the rumbling hadn’t subsided. I told no one about burying the button. The late-night haze had cleared, and the ritual now seemed ridiculous.

I went to see yet another doctor, at a private clinic this time. I paid the 120 złotych (about forty dollars), and a nurse showed me into a room where the doctor sat behind a desk. She spoke some English.

“There’s a crackling in my chest at night when I breathe,” I said, and I told her about the other diagnoses and medications. She nodded, thinking, then asked whether one leg had been swollen. I told her no.

“I see,” she said. “Because I wonder whether you have . . . what is the word . . . zakrzep.”

“A blood clot,” Ewelina translated.

Blood clots, I knew, could lead to sudden pulmonary embolisms, which are often fatal. As I had this thought, the space between me and the floor grew enormous, as if I was looking at the linoleum from far above. Pins and needles rolled down my arms and legs, my jaw clenched, the room grew dim, and I keeled over.

When the darkness had receded and I’d returned to full awareness, I was lying on a hard bed. Three or four nurses hovered over me, pulling up my shirt, unbuckling my belt, attaching suction cups to my chest. A printer began buzzing, and squiggly readings — of my heart? — emerged.

Then came a bumpy ambulance ride to a public hospital — built, I suspected, around the time of the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw. A young orderly in a red jumpsuit pushed me inside and parked me in Observation Room A. I was moved to a cot, just a board on wheels with thin padding. More than a dozen other patients lay in the room, all of us under the watch of a young nurse who squirted sanitizer on her hands every few minutes. I didn’t know where Ewelina had gone. (Visitors were not permitted.) I was the youngest one there, and many of the others seemed close to death. They groaned and gurgled and muttered in Polish. A woman kept trying to escape: she would wait for a staff change, then slide off her bed and go for the door. But each time, orderlies would come and wrestle her back into bed. Another patient squirmed, eyes closed, and moaned every few minutes, “No, no. But no, but no.” That much I could understand.

Above the door was a large cross. On one wall, painted on a wooden plaque, was a blue-eyed, sanguine-looking Christ with his hand raised.

I waited in Observation Room A for hours. Finally Ewelina appeared and wheeled me into a wood-paneled room to see the head physician, a fat, oily-haired man who feared I had deep-vein thrombosis — in other words, a blood clot. It would require surgery, he said, but he wanted to do more tests first.

At this talk of clots deep in veins, panic rose in me again, and while I was having blood drawn from the back of my left hand, I blacked out a second time. I was taken in a wheelchair to Observation Room A to wait for the prognosis among the suffering, the old, the dying. Shaken, surrounded by Catholic icons, and awaiting my certain doom, I looked up at faded wooden Jesus on the wall and thought how lovely it would be to believe.

And for a moment I did. And it was marvelous. I had the feeling that I was in good hands. I didn’t know whose hands they were, only that they were good and that, no matter what happened, I would be OK.

An hour later, when my blood results were in, the doctor told me all was fine. I was low on potassium, but nothing was seriously wrong. It was probably just nerves. He told the nurse to put me on an IV. I could go home when it was done.

That evening, when I got back to Ewelina’s mother’s house, I would figure out why my lungs had been rumbling: my pillow and blanket were stuffed with goose down, and I was allergic. I had known this as a child but had forgotten. Once the blankets were changed, the rumbling would go away.

But as I sat in the hospital with an IV in my arm, listening to Leonard Cohen on my headphones, I pondered the crucifix. I hadn’t become a believer. My commitment to rational principles remained. But in the midst of great fear and sadness, I’d felt a strange peace.