Cactus Country RV Park was nearly empty, save for a few year-rounders’ trailers sparsely dotting the landscape. With school out for the season there was nothing much to do but languish in the afternoon heat, which on some days could climb as high as 110. Too hot even for the swimming pool. As the only two kids left in the park, Aiden and I spent our summer vacation chasing the shade, looking for any reason to hang out wherever the air conditioning was.

Aiden reminded me of a Norman Rockwell painting I’d once seen, with his big ears and freckles and devil-may-care grin. He was ten, and a little short for his age, with a tiny bald spot right at the top of his head where the ringworm had been. Lots of Cactus Country boys had caught it earlier that year from the dogs, who got it from rolling around in the dirt. Like most, I had the rings pretty bad up and down my arms, but Aiden got it worst out of everyone. Six months later and the hair still hadn’t grown back. Kids used to pick on him for it, calling him an “old man,” provoking him until Aiden ran crying to his trailer. But the kids had all moved away now, and no one in the park cared about Aiden’s bald spot anymore.

Though I was only a few years older than Aiden, his mom paid me to keep him out of trouble while she worked. Sometimes she left for a few days at a time, and Aiden spent the night in my family’s Airstream, sleeping on a makeshift bed of couch cushions. Other days she had friends over—different ones every time—and locked Aiden out of the trailer while they did whatever it was she liked to do on her days off, which I’d heard some of the neighbors speculate around the picnic tables might be methamphetamine.

Aiden didn’t seem to mind the babysitting arrangement so much. I always took him to the Cactus Country store and got us ice-cream sandwiches with some of the money his mom gave me. We’d buy them one round at a time, eating them on a bench right outside the store before they melted in the summer heat. On days like that we mostly did whatever Aiden wanted to do, usually hunting around the desert for jackrabbits with his .22-caliber rifle or catching lizards with our bare hands. Aiden was a terrible shot, but I’d never seen a lizard get away from him. He dove after them with the abandon of a baseball player sliding into home plate.

One afternoon as I sat on the fold-out couch in the Airstream playing a video game, Aiden came rushing through the open door, his face covered in blood.

“Jesus, Aiden!” I said. “What happened?”

“Look!” he said breathlessly, holding up the fat yellow lizard squirming in his grip—a horny toad—with both hands for me to see. Horny toads blend in with the desert sand, making them hard to spot. One of their natural defenses is to squirt predators with acidic blood from the corners of their eyes.

“Doesn’t that hurt?” I asked, pointing to the red on Aiden’s brow.

“Yeah, stings a little,” he said. “But here, feel of her.” I ran my fingers over her sharp, armored body and rubbed the soft flesh of her underbelly. Aiden charged me with holding on to her while he washed his face. I expected the lizard to attempt an escape, but she seemed calmer now, maybe in shock.

“What do they eat?” I asked when Aiden came back.

“Probably ants,” he said. We lugged a heavy, ten-gallon fish tank out from under Aiden’s trailer and washed the dust from its interior with a hose. I sifted handfuls of coarse desert sand through an old kitchen sieve to line its bottom. Aiden furnished the tank with some leftover hollow logs and a shallow water dish shaped like a rock from his last lizard. We used sticks to lure black ants from a nearby hill and knocked them into the habitat, but the horny toad wouldn’t go for them. Some of them crawled over her mouth, but she didn’t move, not even to blink. She just stood there, stiller than stone.

“Isn’t she beautiful?” Aiden kept saying. “Don’t you think she’s beautiful?”

Dave had shown up in the park one day that same summer, soon after the last snowbirds had gone for the season. He was twenty-seven and lanky, with blond hair shaved close to his scalp, wire-framed glasses, and a faint goatee. He introduced himself to us as David Davis—“The Third,” he said. “But just call me Dave.” I’d thought only kings went by titles like the Third. His formality suggested pride in a familial legacy that the dusty camper trailer behind him seemed at odds with.

“Zoë Bossiere,” I said dryly, extending a hand. “The First.”

Dave laughed. “That’s funny,” he said, still giggling as he shook my hand. “That’s real funny.”

In the hotter months Cactus Country was less a vacation campground and more a land of lost and wandering souls. Like most everyone else who moved to the park during that time, Dave didn’t know how long he would stay or where he would go next. He smoked roll-your-own cigarettes in his trailer, which was just big enough for a twin bed and a minifridge he kept stocked with that week’s cheapest beer. Dave also had an air conditioner, and for this reason Aiden and I went over daily. That, and to play with Dave’s cat, Buster.

Buster used to live with Aiden. But earlier that month Aiden’s mom had declared she didn’t have the money to pay for cat food and litter anymore. They’d had Buster since he was a kitten. Aiden hadn’t cried when he told me, but I could tell he was upset from the way he’d squinted at the ground, kicking at the dirt. Dave must have been able to tell, too, because he offered to keep Buster for him. He said Aiden could come over to see the cat anytime he wanted.

Dave’s trailer was littered with newspaper, dry cat food, loose beer tabs, stray bits of tobacco, and torn girlie magazines. He had a vast collection of knives he let us play with, including a Wolverine-like claw he kept hanging over his bed, and five well-worn copies of the same book in various colors stacked neatly together on a shelf. I picked up the nicest of the set, one with a blue cover with golden letters and a sword emblazoned on the front. It smelled musty and old.

“Be careful with that,” Dave said, raising a lighter to the cigarette between his lips. “It’s one of the special editions.” I opened the book to its title page and studied its stylized typeface.

“Mean Camp-f,” I whispered aloud to myself, sounding out the words. Since Dave had more than one copy, I thought it might be a religious text—something ancient and holy. I was used to seeing Bibles and prayer books out on picnic tables, but I’d never heard of this book.

“Why do you have so many?” I asked, flipping through it to look for pictures.

Dave shrugged from his spot on the bed, blew a puff of smoke from the cigarette. “I don’t know,” he said. “I just think he’s got some interesting ideas, that’s all.” I couldn’t be sure who Dave was talking about, but I nodded anyway. That was more or less what I’d heard people say about Jesus too.

Later that afternoon, in the Airstream, I asked Dad about Dave over tuna-fish sandwiches and warming cans of soda. Dad had been working odd jobs that summer along with his usual window washing. Sometimes he’d hire Dave to come along and help out for the day while I stayed in Cactus Country with Aiden. He’d even found Dave steady work at a plant nursery as a landscape apprentice. Dad didn’t seem to like Dave all that much, but helping people like him—those who wandered into the park with nothing—was one of his mysterious ways.

“Why do you think he has all those books?” I asked. Dad exhaled a long, frustrated breath through his nostrils.

“Because he’s a fucking idiot,” he said.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Dave’s a skinhead,” he continued, taking a bite of his sandwich.

I raised my eyebrows. “A what?”

“A Nazi,” he said thickly. I’d heard of the Nazis in school, how they’d collected Jewish people and forced them into labor camps. Gassed them with poison in group showers. I’d seen black-and-white photographs of the piles of emaciated bodies that soldiers found in the aftermath. But I’d thought the Nazis were all dead. The bad guys who lost a long-ago war. An enemy to be destroyed in video games with names like Call of Duty.

“Is Dave bad?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Dad sighed, shaking his head. “He’s just an idiot, that’s all.”

Sometimes Aiden’s mom would let him go into the desert with Dave to practice his shooting. They’d head out in the morning with Aiden’s gun and a jug of water, coming back an hour or two later covered in sweat, red-faced and rabbitless. I never wanted to go along on their hunts.

“Lots of ways to catch something without a gun,” I teased.

“Ain’t nothing wrong with guns,” Dave said. “I had a rifle just like that when I was his age. My dad taught me to shoot.” I shrugged, guessing Dave probably liked to see himself as a kind of father figure, since Aiden didn’t have one. And even if he was an idiot, like Dad said, Dave seemed nice enough a lot of the time. He’d tell us dramatic stories about growing up in rural Virginia. How he’d fought his way into manhood, breaking knuckles against skulls and making some decent money selling weed. He showed off his faded green tattoos, most of which he’d gotten in prison, with pride: skulls and eagles and crosses and symbols I couldn’t begin to recognize.

At times Dave seemed ecstatically, almost impossibly happy. He talked about his new chance at life here with us in the Sonoran Desert. His little trailer offered him everything he needed. He had good neighbors to drink with. A job he was beginning to love. Everything was perfect. But other times Dave sank into a despair so deep he seemed beyond reason. Aiden and I would go to his trailer to find it locked, the air conditioner running, Dave’s car parked out front. We’d knock and knock, but nobody would answer. Neither mood seemed to last more than a day or two, though, and soon we’d be back in Dave’s trailer with Buster, listening to him tell his stories again.

One morning Aiden pounded at his own trailer door, yanking at its metal latch in vain. His mother had locked it before leaving for work. Aiden’s .22 rifle was inside, visible through the window but out of reach. He wanted to hunt rabbits with Dave, and they couldn’t go without the gun. Aiden screamed, kicking the door so hard he left a deep dent where his foot had been. Dave and I stood watching from the road. When Aiden got worked up, it was near impossible to intervene. I’d learned to stand back and wait for the anger to run its course.

“I was a lot like that at his age,” Dave said wistfully, taking a drag from his cigarette.

“What, acting stupid?” I asked.

“No, I mean it,” Dave said. “It’s hard to be a boy, you know?”

I nodded, though I didn’t quite understand what Dave was getting at. Even on the hardest days being a boy always felt easier, more natural to me than being a girl ever had. I associated boyhood with coolheaded stoicism, rugged self-reliance, the freedom to live on my own terms the same way Dave seemed to in the stories of his youth. But maybe there was something darker and more dangerous about the kind of boy he’d been, the kind of man he was, than I knew.

In the three years I’d lived in the park, I’d known a lot of boys who made games of knocking baby birds out of their nests and kicking the pads off prickly pears in the cactus gardens. Boys whose rage was hot and pulsing, like the palms of our hands when we dared each other to hold them to the asphalt. Boys who spat insults like fire, who led with their fists, who always drew first blood. But Aiden wasn’t like that. He was always gentle with animals, and I’d never seen him get into a fight with anyone. Watching Aiden take one last swing at the door, I wondered what else Dave thought he saw in him that I couldn’t.

On a hot July afternoon Aiden and I went by Dave’s trailer to cool off in the air conditioning and play with Buster. The camper door was shut, but Dave’s green car was parked outside, so we knocked until he answered, a scowl on his lean face.

“The cat?” Dave huffed. “Yeah, fine, whatever. Come see the fucking cat.”

“What’s wrong?” I asked. Dave took off his glasses and pinched the bridge of his nose.

“Just got my paycheck. After the rent, cell phone, gas for my car, food for this one,” he said, pointing to Buster, “I ain’t got nothing left for shit.” He opened the minifridge, saw that it was empty, and slammed it shut again. Aiden and I stood in the doorway, sharing a glance. This was a problem neither of us knew what to do with.

“Yeah, that sucks,” I agreed. Aiden reached for Buster, who rubbed his head against the back of Aiden’s hand. Dave sighed and sat down on the bed, accidentally catching Buster’s tail. The cat hissed in protest, taking a swipe at his leg.

“Damn it!” Dave shouted. “Fucking cat!” He grabbed Buster by the scruff of his neck and hurled him from the bed. Buster cried out as he hit the floor, scrambling to right himself.

“Hey!” Aiden yelled. “Don’t you fucking touch him like that!”

Dave’s face scrunched red with rage. He shoved us both out and slammed the door, the camper shaking from the force. Aiden and I heard another squeal, longer this time. I imagined Dave kicking Buster, or throwing something at him, or stabbing him with one of his knives. We pounded our fists against the door, kicked it with our bare feet until our toes ached. Aiden was in tears, howling so loud I couldn’t hear Buster over him.

“Just give us the cat, Dave!” I called.

“I’ll kill him if you don’t leave me the fuck alone,” Dave said. “I swear I will!”

“You—you pussy!” Aiden screamed, his voice cracking. “Come out here right now, you fucking faggot-assed chicken-shit!” He grabbed handfuls of gravel from the ground and pelted them against Dave’s front door, continuing his tirade through clenched teeth.

“You asshole, you fucker, you goddamn son of a bitch!”

Aiden’s voice was getting hoarse. His face darkened to a deep red, freckles fading into the color. He looked older somehow, his expression so much like the one I’d just seen on Dave. Aiden took a breath and summoned the worst word he could think of. The slur tore nonsensically from his throat, bouncing from the side of Dave’s trailer back at us, the echo of his high voice sounding it again and again. The word seemed to ring through the park, and in its wake came a second of the loudest silence I’d ever heard. I didn’t know whether Aiden was out of breath or just as shocked by what he’d said as I was—as maybe all three of us were—but for that second, the desert went quiet, and all I could hear was the sound of blood beating in my ears with the same ferocity as the sun beating down on our backs.

“What the fuck did you call me, boy?” Dave shouted. We heard a smash, as though Dave had thrown something made of glass against the door. Aiden opened his mouth, ready to start shouting again. But before he could, I grabbed him by the arm and pulled. I dragged him as he wailed, away from Dave’s trailer and into the shade outside the public bathhouse. Aiden gasped for breath, hiccupping from his rage and the heat. I twisted one of the spigots in an empty campsite until the water ran cold and splashed Aiden’s face in it.

“He don’t get to—to fucking touch my cat like that,” he huffed as I wiped his forehead with the sleeve of my shirt. “If I had my .22 right now, I’d go back and kill his ass dead.”

“I know you would,” I said quietly. Aiden kicked at the ground. I put my hand on his shoulder over his sweaty T-shirt.

“Maybe my dad can talk sense to Dave,” I said.

We found Dad in the Airstream and breathlessly filled him in. He nodded without comment or surprise, following us across the park to Dave’s trailer. But by the time we got there, Dave’s car was gone, his trailer still locked. The AC unit was quiet. I pressed my ear to the door as Aiden called Buster’s name. We heard a soft mew. It was the middle of a hot summer day, the temperature easily more than a hundred degrees. The kind of heat where mirages shimmer in the distance and the asphalt appears to melt. Without air the cat wouldn’t last long.

“We have to get Buster out,” Aiden pleaded. Dad fetched a metal bar and pried the door open. Aiden gingerly scooped the cat from the bed, held him close against his body in a tight hug. Dave’s trailer looked even more ransacked than usual. Clothes lay all over the floor. The fridge hung open. His books and knives were gone. Dad shook his head.

“I don’t think Dave’s coming back,” he said.

That fall the neighbors in Cactus Country gathered every evening around the picnic tables to drink beer and shoot the shit. I stood in front of a table, showing off a tarantula I’d caught crossing the road into the park from the surrounding desert. The late summer’s monsoon rains would draw them from their holes and into the waiting hands of children. But it was rare to find a tarantula so late in the year. I alternated my hands as his spindly legs crept across my open palms, gaining no ground. The adults gaped over their bottle necks at the spectacle.

“Won’t it bite?” a man asked. He was a paramedic who worked the night shift three days a week. His boys were a couple of years younger than me and away for the season, visiting their mom someplace a few states over. The man’s new girlfriend, an RN, sat beside him, watching the tarantula with disgusted fascination. I shook my head at his question, playfully asking the woman if she wanted to hold it. She shrieked, laughing into her hands as I brought the spider closer. The adults around us laughed too. The sun hung low in the sky, casting a red glow over our sun-beaten faces. The burn was an inevitability, no matter how much sunscreen we wore.

Once the novelty of the spider had worn off, the adults started talking about Dave again.

“I heard he was mixed up with the Klan,” one man said.

“You think you know a guy . . .” said another, allowing his sentence to trail off into his bottle. Silence, the solemn shaking of heads. After a second round of beers some of the guys started telling raunchy jokes.

“What’s the difference between a man’s job and his wife?” one asked.

“I don’t know, what?”

“After five years the job still sucks!” The men around the table laughed. One even slapped his knee. The women rolled their eyes, the wife of the man who’d made the joke giving him a playful shove.

“OK, I’ve got one,” the RN giggled, taking another sip from her bottle. She burped, holding the back of her hand up to her mouth. “Why do Black guys have such big dicks?” No one had time to guess before she blurted out the answer, an epithet about the coarseness of Black hair.

A few of the adults chuckled. The paramedic laughed heartily, stood up to get himself another beer from the cooler. “Good one,” he said. I furrowed my brow.

“I don’t get it,” I said. All faces turned to me, still standing at the head of the table. I held the tarantula in my cupped hands, one gently over the other like a warm desert burrow. The spider had retracted its legs, huddled into itself. A second or two of awkward silence as the RN looked at me sheepishly, wispy blond strands framing her thin face. I was no stranger to cussing or the gross-out humor favored by middle schoolers. Some of the names the Cactus Country boys and I called each other out in the desert might have made this woman blush. Even so, though I couldn’t say why or how, her joke made me uncomfortable, as though I’d walked in on something I shouldn’t have.

“You’ll get it when you’re older,” the paramedic assured me, but I wasn’t so sure I wanted to. Recently radio shock jock Don Imus had been in the news for the racist and sexist remarks he’d made about the Black women on the Rutgers basketball team. His brother, Fred Imus, happened to live year-round in Cactus Country and was good friends with Dad. After the story broke, I’d heard Fred say the same thing about Don that Dad had once said about Dave, complete with the same sigh, that same look of resignation—as though nothing could be done.

He’s just a fucking idiot.

I hadn’t thought much of it at the time, but as I stood at the picnic table, this same phrase ran through my head, and it became easy to write off the adults as drunk, the woman’s joke as merely stupid. But as I headed away from the group, I wondered what it meant to be an idiot in the way Fred and Dad seemed to think. How often in Cactus Country the things our neighbors might dismiss as idiocy, like Dave and his books, seemed benign to everyone until suddenly they didn’t. In the aftermath the neighbors would piece together a story around the picnic tables from all the signs they’d missed, following them like animal tracks in the desert—the small imprints of a coyote’s paws or the sideways drag of a snake’s long body over sand. The steaming scat and the brittle shed skins and the bones from its last meal.

I’d gone tracking with the Cactus Country boys lots of times. In the desert the signs animals left behind were often imperfect, confusing. An unskilled tracker could easily mistake old tracks for new ones, following the signs for hours only for the trail to go cold, and have to turn back. We never tracked down so much as a desert mouse out there, but I always wondered: Even if we knew exactly what to look for, even if we followed the signs perfectly, even if we weren’t afraid of what we might encounter, what were we supposed to do with the animal once we’d found it?

The tarantula was brown and hairy, his leg-span roughly the perimeter of my open palm. He was beautiful. I thought about taking him home to my terrarium, as Aiden and I had done with the horny toad he’d caught that summer. As I’d done with countless other tarantulas. I’d keep them a few months, but they didn’t last long under my care, no matter how many crickets I fed them. He wasn’t mine to keep. I walked to the edge of the desert where I’d caught him, opened my palm, and watched the spider slowly amble away.

A few weeks after he left Cactus Country, Dave’s trailer was considered abandoned. The park seized it and later put it up for sale. Buster went to live with a couple Dad found on Craigslist, and Aiden moved to Texas. That fall I saw police cars pressed up against the desert’s edge, raining red and blue light on Dave’s green car, stalled in the dirt with hazards blinking, a trail of severed cactus arms and shorn creosote bushes in its wake. Afterward I stood at the picnic table and listened to the neighbors tell and retell the story of how Dave had tried to escape the police. How he’d flung himself from the car in a desperate bid for freedom, sprinting through the sand with the cops hot on his trail, guns drawn. How two of them had tackled Dave to the ground, cholla needles digging into his face as they pressed it into the earth. How they’d hauled him up, cuffed him, and taken him away.

We would never know why Dave had chosen to return to Cactus Country. How the police had found him, or why they’d been searching for him in the first place. Dave’s car sat in the desert for days until a tow truck came to haul it away. The desert foliage grew in and around the place Dave’s car had been, masking the harm he’d caused, and in time it became impossible for anyone to say where exactly it all happened, only that it did.

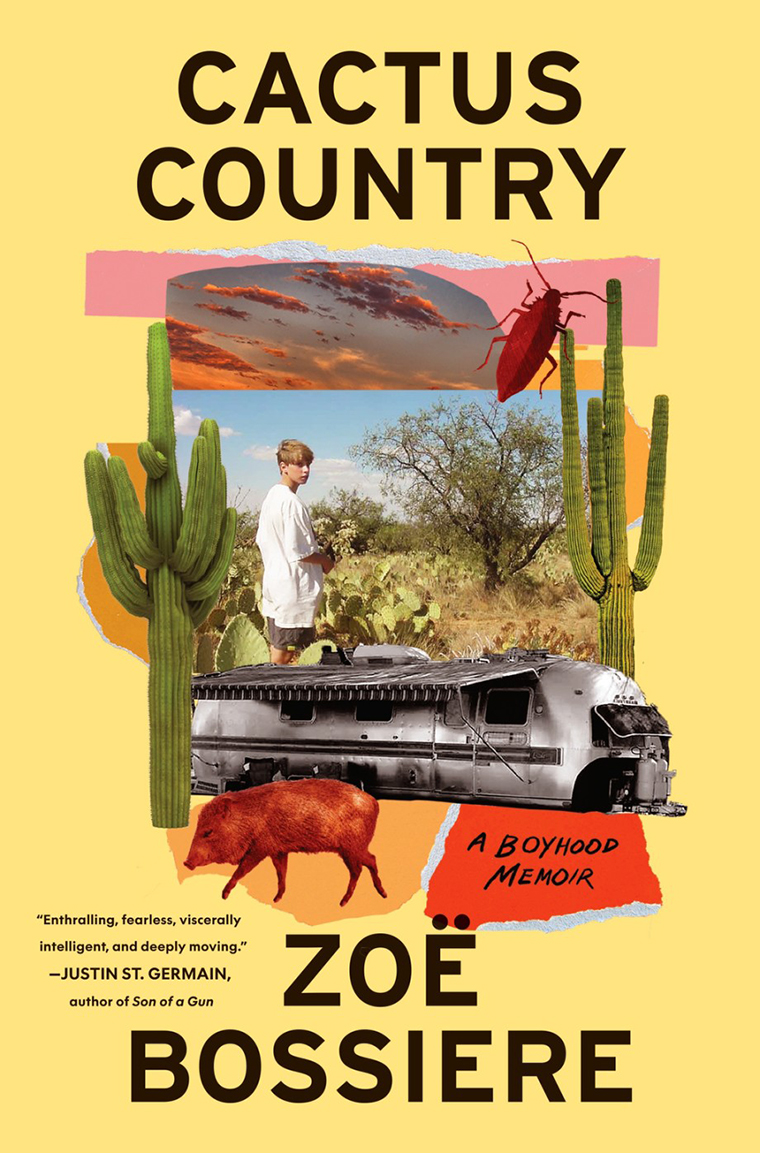

Excerpt from the new book Cactus Country: A Boyhood Memoir by Zoë Bossiere. Copyright © 2024 Zoë Bossiere. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.