What follows are excerpts from Ram Dass’ talk here last May 13.

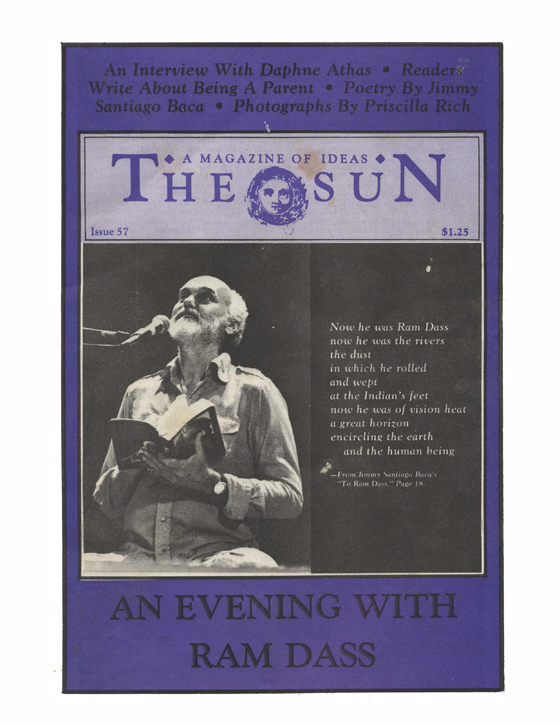

About 1,000 people turned out for “An Evening With Ram Dass” in Memorial Hall on the University of North Carolina campus. This was a benefit for THE SUN. Not only did Ram Dass have kind words for the magazine, but we raised nearly $4,000. (Thanks, too, to the band Silkworm, which opened the evening.)

In our last issue (#56) we printed an interview with Ram Dass, the Harvard professor turned psychedelic explorer turned spiritual teacher. Best known for his association, as Richard Alpert, with acid evangelist Timothy Leary, and, as Ram Dass, for his book Be Here Now, his message has matured since those early days of the consciousness revolution. As we said last month, “his appeal is no longer merely to hippies and rebels, but to a broader constituency; he wears ordinary clothes again and his beard and hair are trimmed short; his own attachments, lusts and fears are discussed with a candor striking for any public figure, let alone a ‘spiritual’ teacher.”

Ram Dass’ guru — Neem Karoli Baba, or Maharaji (an honorary title that means great king or wise one) — died in 1973, but the spirit of this extraordinary saint lives on in Ram Dass’ teachings, and in other ways. In Ram Dass’ latest book, Miracle of Love, he explores his relationship with his guru, and many of the stories he told that night were about him.

This edited transcript leaves out what words can’t convey. There was Ram Dass’ amazing chuckle — intimate, resonant, almost sly, as if he were laughing at a private joke (or a cosmic one). There were the silences. Breathing deeply — inner fingers tracing whatever maps he goes by, by whatever light — he’d pause, for ten or fifteen seconds, at the intersection of his world and ours. Then off he’d go — down the broad boulevards and darkened alleys of his own inner struggles. Some of the streets had foreign names, some were as familiar as your own block. After all, part of Ram Dass’ appeal is his cultural savvy; he translates Eastern ideas into language Western minds and hearts can hear. He’s one of us, reminding us we’re One.

— Ed.

Last night Sy Safransky was driving with me from the airport. We were actually ambling along. He’s got a Rambler except the R and R are missing. And we were talking, about how wonderful my last book was. It’s a book made up of a thousand stories about my guru in India and he said that the quote he liked best was at the end of the chapter about how Maharaji died, or in India we’d say “dropped his body.” This was one devotee’s estimate of Maharaji: “He did everything according to nature. A child stays, a young man moves about, an old man stays. He did according to the laws of nature. If he wanted to, he could, but I don’t think he changed nature for himself. When he was sick, he asked about medicine. When he was tired, he used to rest. When he got old, he died.”

Maharaji had a heart condition and his doctor said, “Take this medicine every day at ten o’clock.” So the old women who were taking care of him are told to give him the medicine at ten o’clock, but at ten past ten they’ve forgotten, and he says to them, “If you don’t take better care of me, I’ll turn your minds against me.” That’s a funny one. Because you realize we’re the only ones that go away from God. God doesn’t go away from us. Our karma is our karma, the veil is the veil of our own separateness.

Now, Maharaji didn’t go around producing miracles, but he was in a universe where there was so little attachment that when he thought of something, it became what he thought. Our own thoughts are so interspersed with other thoughts and ourselves thinking about our thinking, that they have no power, they are not one-pointed like a laser beam. But Maharaji could go somewhere with his thought and find out what was going on and come back and report about it; Maharaji could go there and manifest a subtle body and be there so that people saw him and talked to him, and leave his gross body at home; Maharaji could take his gross body with him. He could walk through walls.

There was an old uncle that was blind. Maharaji was at the house, and the family said to him, “Maharaji, he’s blind, but you could heal his blindness.” And he said, “No, saints in the old days could do that but nobody can do that anymore, everybody’s too impure.” And they said, “Oh, you could do it,” and he said, “No, no, I can’t do it.” Maharaji was always yelling for this and that, and he called for some pomegranate, and had them squeeze it, and then he took a drink of it, and he put his blanket over his face. Somebody looking under the blanket saw two red lines coming out of his eyes, probably pomegranate juice, you think. You think blood, but then you think pomegranate juice. Then he gets up and says he’s got to go to the train. He says to the uncle, “If by any chance God should heal you, and you should see again, you’re an old man and your kids are waiting for you to retire so they can take over the business, they know the business, let them take the business and you spend the rest of your life for God, just devote it to thinking about God.” And the uncle said, “Oh, I will, Maharaji, I will.”

Maharaji left and went to the train station, and about a half hour later the uncle could see. The doctor arrived and said, “This could not be. Who did this?” See, in the West when something like that happens the doctor says, “This could not be,” and then refuses to admit that it is. In the East, he says, “This could not be, who did this?” Somebody said, “It was Maharaji, he’s gone to the train.” So the doctor ran to the train, and he climbed aboard and fell at Maharaji’s feet. Maharaji was hitting him on the back, saying, “This is a good doctor, he’s the man that cured his blindness, he’s a good doctor, he cured the blindness, he’s a wonderful doctor.” Three months later the uncle went back to work and the next day he went blind.

I like those kind of stories. I mean, they have a punch to them. You like them and you don’t because they’re laughing at you. It’s like the Third Chinese Patriarch of Zen. It’s a little booklet. I’ve been spending about six years with this little booklet. I haven’t even gotten through the first four lines yet. Well, you try, before you laugh. I’ll just give them to you: “The great way is not difficult for those who have no preferences. When love and hate are both absent, everything becomes clear and undisguised. But make the slightest distinction, and heaven and earth are set infinitely apart.” See why it may take you awhile?

“For those who have no preferences . . .” You have preferences, I have preferences. What could it mean? What it could mean is that you cease to identify with your preferences, not that you don’t have preferences. But they’re no longer my preferences, they’re just preferences. What’s your favorite color? Blue. Who are you? I am somebody whose favorite color is blue. Definition. Definition, to the extent you identify with it: limitation. You’re already turning off some of the universe. The game is to be full of opinions and attitudes. That’s life. But all the time be sitting in perfect equanimity and spaciousness, and open-heartedness. Doing nothing, yet everything gets done. It’s so easy. All you have to do is give up being who you think you are — give up thinking you are who you think you are, because you aren’t.

You should see what I’m seeing: twelve red-lit signs saying “Exit.” And I’m thinking there is no exit. Those are come-ons. They’ll just lead to more of it. You can’t get out of it by leaving here. You’ll create it wherever you go. You’re the creator. It’s like everybody’s a slide-projector looking for screens. That’s nice. . . . I’m listening too, you know. I’d be bored if I didn’t enjoy this evening. I’m not doing this for you. I’m not even doing this for Sy and THE SUN, although THE SUN is fantastic. I’m doing it because this is what I do. Jerry Garcia plays the guitar all day long; that’s what he does. In his off-time he plays the guitar; that’s what he does. This is what I do. It’s not better or worse than what you do; it’s just different.

Let’s say your occupation is being a mother. It’s awfully easy to get caught in the mother love, isn’t it? There’s a great story about Krishna, who is one of these beings that dropped in full-blown. You see, most of us come in thinking we’re babies, but he didn’t. He wasn’t fooled for a second. There was no karma at all. So he’s lying there in his mother’s arms and suddenly he opens his mouth to yawn and she looks into his mouth and there are the planets and the stars and the universe, and of course she freaks. And then the line is, “At that moment, he veiled her eyes with the veil of mother love once again.” There’s an occupational hazard, because who do you think your baby is, anyway? Who your baby is is who you think you are. You think, I’m a mother, there’s a child.

It’s interesting what you see when you look at other people. You see bodies. Ectomorphs, endomorphs and mesomorphs. Or you see desirable, a competitor for what is desirable, and irrelevant. That’s another category system within that domain.

Or you could flip the channel from the physical. You look around and you see the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory profiles. There’s a manic-depressive with a hysteric overtone, if I ever saw one. People in therapy tend to dwell in that plane. Everybody wants something. I need this. I need love. I need. I need. Who are you? I need. Oh, sorry to bother you, you’re busy needing, I’ll see you later. Who are you? I give. Oh, that’s interesting. As long as you think you’re somebody, you’ve got to have somebody else to complement it. If I think I’m speaking, you’ve got to think you’re listening — this is just a game only one of us is playing. We’re all in drag. Oh, I’m giving. I’m receiving. I’m learning. I’m bored. I’m hot. That’s a good one. [It was a warm evening, with no air-conditioning.] I’m here — that’s a little righteous. If you were, you probably wouldn’t say it.

Then you can flip the channel once more, and you look around and you see there’s only twelve people, and various subtle permutations. You are obviously a Sagittarius. I can see it by the way you are holding your head.

You and I live in all these grids of individual differences. For years, I wished I had more hair. I went around combing it over and around and wishing I had the guts to have a wig. And if you asked me who I was I’d say, I’m somebody who is balding.” If you have a wart and think it’s an ugly wart, you’re busy being somebody with an ugly wart.

I’ve got a fellow staying at my house in Santa Fe. He’s a beautiful guy. He’s twenty-three, he’s English and he’s very charming and erudite and good-looking and athletic. The only thing is, he’s got Hodgkin’s disease and he’s got a huge tumor on his neck and under his arm which is growing all the time. And he said to me the other day, “You know, I’d really like intimacy with a woman, but I feel so ugly.” And I found it so easy to go into it with him. You see how seductive it is? I mean, you can say in the abstract that it’s nothing, but when you see him like this, it’s hard for the first few times you’re with him not to become fascinated with his tumor.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross once told her audience about a nurse who was twenty-eight and had four children and had more than a hundred operations for cancer already. If you came into a hospital room with her, Elisabeth asked, what would you feel? And everybody in the audience had a different feeling — anger, self-pity, anger at God, sadness, fear, tenseness. She then asked them to imagine that they were that nurse, and what it would feel like. Everyone will be so busy seeing you as a cancer victim that nobody will be with you. Everybody is too busy reacting to your symbolic value.

As long as you think you’re somebody, you’re going to die. As Kabir says, you will have an apartment in the city of death.

See how the game would be not to react to the symbolic value? But you can only do that when you’re not caught in a symbolic value of your own. As long as you’re somebody, all you’re going to see out there are more somebodies. If you’re physical, you’ll see physical; if you’re psychological, you’ll see psychological; if you’re astral, you’ll see astral — all in terms of individual differences, to which you will apply the labels “better” and “worse.”

If you flip the dial once more, and you look into somebody’s eyes, you see another person looking back at you, another being in there. The eyes are the windows of the soul. Are you in there? Far out, I’m in here. How’d you get into that one? And you see everybody packaged in these matrices of individual differences. What trip are you running through this time? Oh, this time I’m a sexy blonde. That’s nice. What are you running through? Well, this time I’m a responsible member of the community. Pretty good. Interesting work.

Imagine somebody has just died, and they were quite conscious. I mean, they didn’t die like most people around us die — “Ahh, no! Freeze me! Dry me, do anything, but keep me alive.” But this is somebody that died saying, “Well, here we go. Ohhh.” Dead. Then you’re out there, running through your past life, or lives, whatever the case may be, depending on how clear your vision is. You know, my whole life flashed before my eyes — that one. It’s a low-level, early stage that you can remember if you happen to be resuscitated. So you look at your karmic scorecard, so to speak, and you say, “Gee, I got a lot of energy. I think I’ll take another human birth, a lot of good sandpaper in that.” Human births are really good to have, because there’s a lot of abrasiveness to rub against, to purify. When you’re an angel, it’s draggy, there’s nothing to rub against, it’s all fine, so you can carry karma for thousands of years as an angel. As a human, you get it in your face all the time. So, “I think I’ll take a human birth, and let’s see, I know what I’ll do, I’ll be born into the poorest tribe in Africa, that would be great, because that will take care of the time I was a miserable, cruel king. I’ll get raped at seven — that’ll take care of that one. I think I’ll get syphilis at thirteen, I could fit that one in, and then I’ll go blind at fifteen and I’ll die at seventeen. Okay. Fair enough. Looks like a good one. Cram-packed.”

You build a little sign, saying what you are, because you’ve got to wait for somebody to need you, since we are each other’s karma, and kids are parents’ karma — so it needs two people, two others who need you like you need them. You wait with your sign and the big computer in the cosmos whirs — it’s all outside of time so it doesn’t matter — and sooner or later, two beings appear who need you. “Okay, we’ll go ahead and we’ll call you.” And they go ahead and call you, and you say to everybody, “See you around.” And you go in. “Waah. Waah!” You’ve got to cry, because you’ve got to make it real. If you don’t get stuck in it, it’s not working out your karma. You’ve got to stay right on the edge, stuck but not quite. That’s the whole secret. But if you don’t get stuck at all, you’re like Krishna, you’re just riding through to say hello and spread a few blessings.

Buddha said we have five hindrances. The first one was . . . I wonder why I don’t remember it . . . lust and greed. That’s just the first one. All this time we’ve been treating them as two. Then there’s hatred and ill-will. There’s agitation, and our old friend sloth and torpor, and the fifth one is doubt. Buddha was pointing out that these are really the stuff of which suffering, or clinging, is made. So, giving you the benefit of the doubt, you have to have at least one of them in some subtle form to be here on Earth, because that’s your passport into incarnation, unless you just came to bless us.

Did it ever dawn on you that it’s perfect? Oh God, that’s heresy isn’t it? I mean, every righteous bone in your body is fraught with indignation at this moment. What do you mean, it’s perfect? Cruelty, barbarism, starvation. Auschwitz. Hiroshima. The Shah of Iran. God, you really screwed up that time. I mean, if I were making that guy, I would have made him a heavy until the last minute, and then he would have turned it all over to the people. I don’t understand what your trip is, God. Some kind of sadist? From what place are you judging God? From your little piece of the rock? Oh boy!

As you quiet down, and empty, and get over the polarities — like good and evil, for example — and start to float around the edge of dualism and non-dualism, you come to a causal plane. The laws of the universe. They’re not laws you know with your intellect nor that you can conceptualize, so you never know you know them. You have merely for a moment been them. That’s who you are when you are finished being who you think you are. Then you come back into being who you think you are again, and you have those laws as a memory. You keep evolving until you are resting in the law, you are the law, the One, you are also one of the many. Only initially is the game to get high. Getting high is because of the attachment to one’s separateness. You want to get out of it, you want to be together, you want a union, you want to co-habit, to transcend your separateness, break through. Surfing can do it, or skiing, or riding a motorcycle, or hang-gliding, or trauma can do it, or drugs, or meditation, or sex, even cooking a bouillabaisse, if you know how to do it.

I hope I’m not irritating you because I’m not more godly. Every time I look around to see what godly is, I am forced to conclude that something isn’t, and that fascinates me, so I look at what isn’t and it turns into what is. So there you are. It’s all the beloved.

When you look into another person’s eyes and see the other being looking out at you, you begin to experience that you two are part of another kind of community, a community of the spirit, or of awareness, that doesn’t exist in time and space. I remember once in Nepal, Bhagwan Dass was teaching me Om Mani Padme Hum, the mantra, and I did it for two days, day and night, Om Mani Padme Hum . . . [a number of times]. After about two days, in the middle of the night, I stopped to go to the bathroom, and I stopped but it didn’t. I started to hear thousands and thousands of voices, like ocean waves rolling in all directions, back in history and out through time, timeless. Om Mani Padme Hum . . . and so I freaked. It wasn’t like hearing my own voice, or an imitation of my voice. These were thousands of distinct voices. I went running out to Bhagwan Dass and I said, “You don’t know what I’m hearing.” He said, “You’re hearing the sound of all those that have done that sound purely, have tuned into the sound, have become the sound. A mantra does you, you don’t do a mantra. You just pump it up until it starts to do you, and you’re cooked when you and the mantra become one. Then you’re finished with the mantra, you can use it or not.”

Sometimes I get caught in hindrance number one, lust and greed, and I’m feeling lust in which everyone becomes an object that’s relevant or irrelevant. Lust has a whole projection system which can only be gratified by something you can use to close the circle of the projection. It has no real people in it, it’s just a mind net. You go fishing for something that fits in the net. I see somebody that fits, and I start my tracking behavior, which is, “Hello. I’m Ram Dass. Don’t you want to come and see my holy pictures?” It all too often works, but then I’m faced with this predicament that if I should per chance look into the other person’s eyes, I see my guru — this fat, tough old bastard looking out of these eyes, laughing at me, saying, “Gotcha that time, didn’t I?”

Compassion is to leave people alone to be who they think they are, but if they consider the possibility they aren’t who they think they are, you’re there to be with them when they think they’re somebody different. You’re a good environment for people to be free to grow — instead of, “I know you, you’re Sam and you’ve got a nasty disposition.” Poor Sam. I mean, if Sam should be happy one day, it’s already deception.

We have to stop getting one another in our roles and labeling for efficiency. I want to know who you are, that you’re who you were yesterday, so you don’t screw up, so I don’t have to think about you anymore. You’re my father and you’re this way. Stay it. Keep cool. You fit in that category. I can’t function if I don’t have categories. What happens if I have to look to see who everybody is each time?

Well, you don’t. You play within the roles perfectly, but you’re always available to step out when somebody wants to dance. I remember being pinched for going too slow in my Buick limousine on a freeway in New York State. I had the trunk out — I was living in the back part of it — and it was a beautiful antique limousine on the outside. He stopped me and said, “License and registration.” And I had been driving this big tank for hours and I was doing mantra, and I was so out there I had just enough ground to keep the car going. That’s how they always know, because you’re going too slow. So he said, “License and registration,” but when I looked at him, he obviously was Krishna in drag, he was being a policeman. I saw immediately who he was. I just looked into his eyes. I mean, there was Krishna giving me darshan, right there. How else would he come? “License and registration?” Now I have a choice. I can say, “I know who you are, you’re Krishna.” But that is not what Don Juan calls impeccable warriorness. So I hand him my license and registration, friendly-like, and he looks at them and he checks me out on the radio and says, “What is in that box next to you?” And I said, “They’re mints, would you like one?” And I’m offering this to Krishna, I’m just looking at him with love. And he’s being somewhat guarded. I’m sure people have been shot by people who look at them with love. Then he’s done, but he hasn’t finished with me yet. I can see he doesn’t know why, but something’s happening. Yet it’s a very limiting game because he’s a state trooper. He says, “Nice car you got there.” That’s another gambit you can slide into, another strategy, and you can still be macho in it. “Good car, oh, I mean, back in the twenties we. . . . Once I drove one of these through a snow storm.” “Did you really?” “Straight eight, yeah. . . .” “No, it doesn’t use oil. . . . Fifty thousand. . . .” “That’s amazing.” You can play that for quite awhile. All the time I’m looking at Krishna, saying, “Come on off it.” But I see he’s absolutely perfect in his role. Finally, he gets done and says, “Well, be gone with you,” which is pretty far out already. So I start to drive away, and he walks to his police car and he turns around and I look in my rear-view mirror and he’s waving at me. I was going to stop and say, “You blew it. State troopers don’t wave, baby, that’s just not the way it’s done. Stay in your role. Be impeccable. Glare or something.”

What do we think we’re doing, being humans on this kind of an Earth? Mad. But I look in your eyes and I see you know it too — ah, you have the mark of madness. We call it being in love.

If you aren’t busy being anybody in particular, you can run yourself through these different realities, and see if there’s anything interesting to catch hold of inside you. You run realities through you to see if you’ll grab onto any of them. Walter Cronkite gives you a reality every night. Well that’s real. Ah, got you, didn’t he? That’s because he thinks he’s Walter Cronkite. Imagine if Walter Cronkite didn’t think he was Walter Cronkite. Maharaji said to me, “Lincoln was a great president.” I said, “Why was that, Maharaji?” He said, “Lincoln knew Christ was president. He was only acting president.”

At first we were all trying to get high. We were trying to get to that place where we can look in each other’s eyes and say, “Wow, are you there?” That is a place of love and at first you don’t know how to get there and sometimes you meet somebody that turns you on to it. They become your connection to the place in yourself where you are in love and you say, “I am in love with you.” Meaning, “You are my connection to me exploring the place in myself where I am love” — if you were to say it more exactly. But you say, “I love you,” and you focus in on that person because as long as you’re with that person that thing turns on in you. But in the course of deepening your awareness, you begin to rest in that place more and more, without the need of an external stimulus. You have certain habits of response when that thing happens to you, and it gets very complicated. You meet somebody and look in their eyes and it happens. You say, “Oh God, I love you, let’s build a nest.” Then you say, “I’m going out for tofu and yogurt.” And you’re at the tofu and yogurt store and you’re at the check-out stand and you look into the eyes of the check-outer and there it is again. Because you’re carrying it with you. If you’re Typhoid Mary, every place you look has typhoid. So you say, “Have you considered a menage a trois?” Where do you go from there? Communes? Adamites? Finally you realize you can’t collect on it every time it happens. So you shift gears, and when it happens, you say, “Did you feel what I felt? Wow, I love you. See you around.” “Yeah, bye, we’ll be together forever.” Then you get further out. Because it keeps happening. It gets a little draggy to keep saying that. Finally, you say, “Ah, wow.” And then finally you just widen your eyes a little bit with somebody, and they widen their eyes, and it’s like dimming your headlights for a moment. It’s an acknowledgement that we’re here. Like a club. Like a secret handshake.

There’s a great story about the king whose wise man came to him and said, “I’m sorry but all the wheat has been ruined this year and everybody that eats it, everybody in your kingdom, is going to go mad. But what I have done, as your wise man, is put aside a little of last year’s wheat, so there’ll be enough for you and a little for me, so we don’t have to go mad.” So the king, in a kingly fashion, paced back and forth. Finally, he said, “What would be the value of staying sane if all my subjects are mad? No, we’ll go mad, too.” And then he paused and said, “You know, it would be perhaps useful if we could notice this moment. So let’s put a mark on each other’s forehead so that every time we meet we’ll know we’re mad.”

What are you and I doing in Chapel Hill, North Carolina? What do we think we’re doing, being humans on this kind of an Earth? Mad. But I look in your eyes and I see you know it, too — ah, you have the mark of madness. We call it being in love. It’s just a widening of the eyes. Finally, you don’t even do that. You just meet eyes and go on. That’s when the faith is really not flickering. As long as the faith flickers you’ve got to run it through someone else to make sure, to validate it.

Do you need a guru? Well, if you’re busy asking that question, you’d never know if one walked up to you. If you just open, whatever happens, happens. You don’t need one anyway. You’ve taken an incarnation that is absolutely perfect to work out your karma. I’ll tell you how form-fitted it is. It isn’t just some schlock, factory-ready garment. This thing is so tailor-made that every experience in your life — every single one of them, what you felt on the toilet this morning, every one of them — is designed within that game to awaken you, if you want to use it. You’re given an entire road map out. Every step you take is another step on it, the minute you see it’s a road map. If you don’t see it’s a road map, you just walk over it like a piece of old newspaper. Which one you do is your karma. It’s all in the map. At some point in the map it says, “At this point, awareness becomes aware it’s a map.” You have to realize that you’re in prison. If you think you’re free, there’s no hope for you at this point. Being in prison means I’m identified with the storyline. I’m busy being the butler in the pantry, instead of the person who’s reading the book. Let alone, the person that wrote the book — which is who you are. And you are the book. Once you realize that, getting high is merely a device to release your attachment to the place you thought you were. Then you begin to be fascinated with why you come down. As you focus on why you come down you begin to suspect that you are treating down, down. You’re treating it in some pejorative way. Alan Watts was the first one that said it to me: “Dick, your problem is that you’re too attached to emptiness. Imagine a microscope, a culture on a slide, and the microscope is out of focus so that when you look into the microscope, you see a homogenous white field. But then as you focus the microscope, you bring the slide into focus and you see the culture. And you see all of the exquisite forms that God takes.”

He was describing another part of the cycle. Because the cycle is that you go from the many into the One, not to sit in the One, but to come back to play in the many. And it is play as long as you are rooted in the One, and at play in the two. If you are only rooted in the two reaching for the One, the two is all too real and it’s not yet play, because there’s a lot of suffering. Because you’re still attached. Suffering is the result of attachment or clinging.

A truly conscious relationship is two people coming together in order to use the relationship to know the One, to be the One, at which point there is only one of them with two bodies, and they play as two. They go between two and one and two and one. A true bhakti, or devotional, yogi gets it down to almost every breath. It’s like being in a sexual embrace in which you go in and out of union with your partner. So now there is somebody enjoying it, and then there are no enjoyers, there is merely, “Unh.” It’s like, “Here I come here I come here I come. That was great that was great that was great.” But at the moment, there’s nobody around. See? You go between moment and the separateness. Like Hanuman, the monkey, who is the perfect servant of Ram, who is God, in the Ramayana. Hanuman is kneeling at the feet of Ram. He’s found the lost wife of God — Sita. Ram feels very indebted to Hanuman and wants to lift him up and sit him next to him. That means they would merge into Oneness. Hanuman makes himself like stone in order to stay separate, so he can enjoy his beloved. Now that’s an interesting one. You enjoy and then you merge and you enjoy and you merge.

Ramakrishna said, “People weep for their children. They weep for their relatives. They weep for their parents. They weep for their money. But, who weeps for God?” The only reason for a relationship among conscious beings is to awaken. That’s it. The rest of it is just part of the melodrama. How to deal with the melodrama? That was my problem. And then I saw that the game is closing the circle and coming right back into the forms, so you are in the world, but not of the world. Suddenly, the thing to get me to God was learning how to be a good son to my father, a good citizen, an ecologically conscious being, a socially caring human being, learning to remember my zip code, and do my laundry, and having integrity about my being. I had to have relationships, and jealousy and rage and anger. I had to bring it all out of the closet all over again. I was so busy being Ram Dass because I was trying to be out there and everybody was saying, “Come hear Ram Dass, he’ll get us out there.” Sure it’s fine for me to be out there, but I’m also right here. And I’ve got to stop putting it down and putting it away. I’ve got to work with it and live with it and love it and honor it and find God in it. [Applause.] You just have to be careful that applause doesn’t come out of your attachments.

The final trap about bringing it all home is that you’re going to get caught in it. And the one you’re going to get caught in, in the last analysis, is righteousness, doing good. It’s a real drag. It’s a stance. “I do good.” Don’t get lost in giving and receiving. Because if you’re a giver, someone else has to be a receiver, and that keeps you both separate, keeps you within your roles. “You a giver? I’m a receiver. Great.” It’s the symbiosis of the illusion of separateness.

Suddenly, the thing to get me to God was learning how to be a good son to my father, a good citizen . . . learning to remember my zip code and do my laundry and having integrity about my being.

If you keep meditating through all polarities, and go from dualism into non-dualism, and then come back, you see that all polarities are merely relatively real, including good and evil, and that behind good and evil here we are. I do crummy things, I do beautiful things. Does that mean I’m good or evil? I’m neither. I just am. We will collaborate to create a conscious set of laws to stop the crummy things, and we will help along the good things, within that plane of relative reality. But don’t think that’s real. It’s just relatively real. Once you are rooted in the One, then you can play at the two, and it turns out that you don’t kill and you don’t steal. I look at you and you are me and I am you. So who am I going to steal from? I put out the six-record album, “Love, Serve, Remember,” in a box a while back. It was a beautiful box with a set of photographs and words and six records mail order to you for $4.50. My father looked at it, and he said, “Very impressive.” He said, “You know that thing must be worth. . . . you could get fifteen dollars for it.” I said, “That’s right.” He said, “Why are you only charging four and a half?” I said, “Well, it only cost me four and a half.” He said, “Wouldn’t people pay for it if you charged fifteen?” I said, “Yes, they’d pay for it.” He said, “I don’t understand you. Are you against capitalism?” I said, “No.” I was trying to think of a way to share with him the predicament. I said, “Dad, remember you tried this case for Uncle Henry?” “Yeah.” “Was it a tough case?” “Oh, it was a stinker. I worked in the law library weeks.” “You must have charged him a healthy fee, because you know you charge good fees.” “What, are you out of your mind? It’s Uncle Henry.” I said, “Well, that’s my predicament. Everybody is Uncle Henry. If you show me somebody who isn’t Uncle Henry, I’ll rip him off.”

With the One deeply embedded in your being, you live in the two, in a purely dharmic way, because that’s merely the form you manifest in, because who wants new karma? You’re just old karma running off then because you’re no longer creating new karma — because karma arises from attachment. I use the words “karma” and “reincarnation” realizing that all of these are meta-illusions and that behind it nothing has happened. There is no time and there is no space, there are no forms, as every self-respecting quantum mechanist now tells you. The universe you see yourself to be living in is your own projection of your own karma. Which scenario do you want? How about the scenario that you and I are very, very high beings. We’ve been waiting around thousands of years for a unique opportunity to take birth in a situation that could be our last incarnation. It would be a particularly fierce one because everything would be destroyed and fall apart. And then finally the paranoia would be so great that somebody would push a button, and there would be a big mushroom cloud, and we would all get enlightened. Do you like that scenario? It’s just as real as the others. In that case, “No, no don’t push the button. . . . Hey, baby, push the button, come on, we want to get enlightened.” The secret is not being attached to any of the scenarios, functioning within all of them.

How do you function within all those different scenarios? Are we these high beings waiting to be enlightened by the bomb? Are we part of the new age that is going to convert the Earth into a beautiful consciousness garden? Are we going toward more and more destruction and paranoia, and ugliness and heaviness, which is finally going to end in just yecchh? Who could you be if you are trying to live in all three scenarios? Well, you would do just what you came to Earth to do. You would use each experience as a vehicle for awakening out of the illusion of scenarios. And you would find a way to do that perfectly within each scenario by doing what you had to do. You end up being much less attached to what you do. Everybody says, “What do you do? And what will you do then? What are you going to do when you grow up?” Finally you just do what you do. “I’m going to the bathroom now. Now I’m going to wash my hair. Now I’m going to buy a shirt.” A river doesn’t say, “Now I’m going to turn left. Now I’m going to glisten.” A river is mindless in the sense that it’s not self-conscious. It’s pure consciousness. It’s pure awareness. It’s pure love. It’s pure presence.

One night I was invited by a number of pushers to share in some LSD at Owsley Stanley’s house. The ceiling was all decorated psychedelically. And there was the purest acid. It was so pure I took it intravenously. And I had just time to lie down as I went out on an elevator, out into the cosmos. I was having a wonderful trip, just like going to the moon, going to la-la land it’s called. As I was soaring out, I felt a tension below. I looked down, and there was one of the young pushers having a bad trip. Owsley was standing next to him with The Psychedelic Experience, the manual based on The Tibetan Book of the Dead that Tim Leary and Ralph Metzger and I put together. He’s reading to him from it. So, I figure I’m being called. I’ve got to go to work. I pull myself back into form. I get up, and I walk over, and I fall on top of this guy and I whisper in his ear, “Now that you’ve got all our consciousnesses, what do you want to do with them?” He turns to me with total hate in his eyes and he says, “I’m going to take my chick, and my motorcycle, and I’m going to get my .38 and come back, and blow your fucking brains out.” And I looked into his eyes and said, “If you do that, you’ll be killing a really beautiful guy, but if you’ve got to do it, you’ve got to do it.” So, he got up, and the girl didn’t want to leave, of course, so he grabbed her. He headed for the door, black leather jacket, fury. Everybody was stunned. And I said to him, “Well, we’re going to stay here be because it’s nice and warm. We are your friends, but you don’t think so, so you go and do whatever you’re going to do, but on your way — you obviously don’t trust any of us — you could look up at the stars, because they are certainly trustworthy.” The door slammed and we all sat there in our own thoughts. After about three or four minutes, the door crashed open. He was sobbing, and he came in, and he fell in the middle of us. We were all through it at that point. He had gotten caught in the reality of a mind projection, but running it against the stars just cleared his head. He heard the message, and he was ready to let go. What we often need are those kinds of mirrors in order for us to see the ways in which we are caught in our mindsets, in who we think we are.

But that doesn’t always work. I was with a couple yesterday in Washington State. They said, “Won’t you stay at our house? We’ll take care of you and we’ll love you.” I thought, “Well, I usually don’t do that, but okay.” I came into their house. It was the day they had a terrible fight. So, there are the two of them. She is hysterically rushing around the kitchen cooking. He is sitting solemnly in the corner. The kids are screaming, and I think, “What have I done to deserve this one? Ah God, this is a good one. I thought I was going to get a day off.” I realized, as Maharaji said, “You don’t have to change anyone, just love them.” If it’s their karma to fight, then it’s none of my business. But I’m there, and I love them. Every now and then one of them would come and bounce against me in one way or another. The minute I wouldn’t buy into the trip they’d walk away disgusted. Because each one is saying, “This is how it is. You see how it is, don’t you?” I’m saying, “Right. And that one, too. Here we all are.” “No, you don’t understand.” And they would walk away.

You’ve got to want to let go of your trip. If you want to keep it, keep it. Ten thousand births. . . . Go right ahead, no rush. Do you know what kind of a time scale we are dealing with? Buddha describes it: a mountain, six miles long, six miles wide, six miles high. And every hundred years a bird flies over it with a silk scarf in its beak, running the scarf across the mountain once every hundred years. In the length of time it takes the scarf to wear away the mountain, that’s how long you and I have been doing it already. You know those bugs that are born in the morning and die at night. Around noon they say, “Boy, this is life.”

Finally, compassion is to stop laying trips on each other, to do what you do so impeccably that you are a statement who attracts, just by the nature of your being. Mahatma Gandhi was in a train pulling out of a station with reporters running along the platform saying, “Mahatma-ji, would you give me a message to take back to the people.” The train is picking up speed and Gandhi just had time to scribble on a piece of paper bag which he hands to the guy. The paper says, “My life is my message.”

So it is with each of us. Our life is our message. You have to honor all of the individual differences within the way karma manifests. But, in everyone, when done purely, it brings you into such a state of grace that the light pours out of you, and everybody looks. As Ramakrishna says, “When the flower blooms, the bees come uninvited.”

There is a wonderful doctor, Larry Brilliant, who is with the World Health Organization. His wife was in India where she met Maharaji. And she came back to America to get him. He was a pretty hip doctor. He was a political activist at Berkeley in the sixties. And he had been in Cuba. [He reads from Miracle of Love] “My wife had met Maharaji, had come to get me in America and bring me back to meet him. When we first went to see Maharaji I was put off by what I saw. All these crazy Westerners wearing white clothes and hanging around this fat old man in a blanket. More than anything else I hated seeing Westerners touch his feet. On my first day there he totally ignored me, but after the second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh days, during which he also ignored me, I began to grow very upset. I felt no love for him. In fact, I felt nothing. I decided that my wife had been captured by some crazy cult. By the end of the week I was ready to leave. We were staying at the hotel up in Nanital and on the eighth day I told my wife that I wasn’t feeling well. I spent the day walking around a lake thinking that if my wife was so involved in something that was clearly not for me, it must mean that our marriage was at an end. I looked at the flowers, the mountains, the reflections in the lake, but nothing could dispel my depression. Then I did something that I had never really done in my adult life — I prayed. I asked God, ‘What am I doing here? Who is this man? These people are all crazy. I don’t belong here.’ Just then I remembered the phrase, ‘Had ye but faith, ye would not need miracles.’ ‘Okay God, I don’t have any faith. Send me a miracle.’ I kept looking for a rainbow, but nothing happened. So I decided to leave the next day. The next morning we took a taxi down to Kenshi to the temple to say goodbye. Although I didn’t like Maharaji, I thought I’d just be very honest and have it out with him. We got to Kenshi before anyone else was there and we sat in front of his tucket, the wooden bed on the porch. Maharaji had not yet come out from inside the room. There was some fruit on the tucket and one of the apples had fallen on the ground, so I bent over to pick it up. Just then Maharaji came out of his room and stepped on my hand, pinning me to the ground. So there I was, on my knees, touching his foot, in that position I detested. How ludicrous. He looked down at me and asked, ‘Where were you yesterday?’ Then he asked, ‘At the lake?’ He said ‘lake’ in English, the rest was in Hindi. When he said the word ‘lake’ to me, I began to get this strange feeling at the base of my spine, and my whole body tingled. It felt very strange. ‘What were you doing at the lake?’ I began to feel very tight. ‘Were you horseback riding?’ ‘No.’ ‘Were you boating?’ ‘No.’ ‘Did you go swimming?’ ‘No.’ And he leaned over and spoke quietly, ‘Were you talking to God? Did you ask him for something?’ When he did that I fell apart and started to cry like a baby. He pulled me over and started pulling my beard, repeating, ‘Did you ask for something? Did you ask for something?’ That really felt like my initiation. By then others had arrived, and they were around me, caressing me, and I realized then that almost everyone there had gone through some experience like that. A trivial question such as ‘Were you at the lake yesterday?’ which had no meaning to anyone else, shattered my perception of reality. After that I just wanted to rub his feet.”

I do crummy things, I do beautiful things. Does that mean I’m good or I’m evil? I’m neither. I just am.

Since you can’t be attached to any scenario, you merely work to bring the world back together again, and then how it comes out, it comes out. It’s always in the law. Relax, do your part. Don’t get freaked about the outcome. It doesn’t matter. It’s all doing fine. And the way it happens is by living in a world of us. But, you’ve got to start, first. “Do what you do with another person,” Kabir says, “but never put them out of your heart.” Do whatever you do, fight them, kill them, but don’t put them out of your heart. If you can keep another being with you in love, you can do anything. We used to do parent-child research in psychology. And it turned out it didn’t matter whether people spanked their children, or didn’t. It was how they did it. You could spank your child in such a way that they just got more and more loving and open and beautiful. You could spank them in such a way that they became neurotic little monsters. It depends on who you thought you were. Were you the lover or the spanker? If you were the spanker you were really creating conditional love. If you were the lover you were creating unconditional love and just straightening up a sloppy act.

There’s a couple in Ashland, Oregon. You may have read about it. They had a twelve-year-old girl who went out to play tennis with another girl and both were sexually assaulted and murdered. Somebody sent me the clipping, and said, “These people have read your books and listened to your tapes, and it would be nice if you wrote them a letter.” I opened my heart to the situation and the pain was so unbearable. Somebody as innocent and precious as that going through that at the last moment of life. The agony was so great I couldn’t imagine what kind of a letter I could write. And I had to meditate for hours to get free of the power of that storyline. Here’s the letter:

“Steve and Anita, Rachel finished her brief work on Earth and left the stage in a manner that leaves those of us left behind with a cry of agony in our hearts, as the fragile thread of our faith is dealt with so violently. Is anyone strong enough to stay conscious through such teachings as you are receiving? Probably very few, and even they would only have a whisper of equanimity and spacious peace amidst the screaming trumpets of their rage, horror, grief and desolation. I cannot assuage your pain with any words, nor should I. Your pain is Rachel’s legacy to you. Not that she or I would inflict such pain by choice, but there it is. And it must burn its purifying way to completion. You may emerge from this ordeal more dead than alive. Then you will understand why the greatest saints, for whom every human being is their child, shoulder the unbearable pain and are often called the living dead. For something within you dies when you bear the unbearable. It is only in that dark night of the soul that you are prepared to see as God sees, and to love as God loves. Now is the time to let your grief find expression. No false strength. Now is the time to sit quietly and to speak to Rachel and to thank her for being with you these few years and encourage her to go on with her work knowing that you will grow in compassion and wisdom from this experience. In my heart I know that you and she will meet again and again and recognize the many ways in which you have known each other. And when you meet you will know in a flash what now it is not given to you to know, why this had to be the way it was. Your rational mind can never understand what has happened, but your hearts, if you can keep them open to God, will find their own intuitive way. Rachel came through you to do her work on Earth which included her manner of death. Now her soul is free and the love that you can share with her is invulnerable to the winds of changing time and space. In that deep love include me too.”

The paradox: it is all perfect and it all stinks. A conscious being lives simultaneously with both of those. You huff and puff and you make to appear as if it were real, but you know it isn’t. You experience the agony and the ecstasy and behind it you sit, laughing at the moon. It is perfect, and you do everything you can to relieve the suffering, wherever you find it. What else is there to do? And you recognize individual differences — that what is suffering for one person is not suffering for another. Somebody comes to me and says, “You’re a yogi. Tell me how to fast.” I say, “Don’t eat for nine days.” “Well, I’d thought of a four-day fast.” “No, do nine, it’s good.” “Can I take anything?” “You can take weak tea.” After seven days, the person comes in and says, “I haven’t eaten for seven days.” “Good, doing fine, two more days.” You give a little ego boost. You walk out on the street and somebody comes up and says, “Hey man, you got a quarter? I haven’t eaten for seven days.” “Good! You’re doing fine, two more days.”

You only suffer if you are attached. If you think you’re young and you start to grow old, you suffer because you’re busy thinking you’re young. If you’re not standing anywhere, where is the suffering? No pain. So, you finally realize it’s as if you jump out of an airplane and there’s no parachute, but there’s no Earth. You could just keep doing it. It’s all skydiving from there on in. So, for a person who realizes that, suffering — although you don’t go after it because you’re not a masochist — isn’t pushed because you realize it’s teaching you something.

I work with dying people. And the people who seek me out are the people who have said, “I wish to use my death as a vehicle of awakening,” which is a really select sample. I walk into a room of people, even these people, and I look, and I say, “Oh, I’ll come back later, I see that you’re busy dying.” One woman says to me, “Ram Dass, I’ve finished my work and I want to die. I want you to help me.” She’s got a big brain tumor and she’s on oxygen and she’s very frail. I say to her, “Sounds like ego. How do you know when you’ve finished your work? Maybe you’ve got to lose each sense, sense by sense. Take whatever you can get.” She reflects on that and she says, “But I’m so bored.” I said, “Of course you’re bored. That’s because you’re always busy dying. I mean you’re dying and so am I, but I’m not busy dying.”

If you try to keep one story line going it’s boring. “I’m a husband. Every day. I eat like a husband. I drive like a husband.” It gets boring. I wouldn’t like to be a husband all the time. I wouldn’t like to be anything all the time. I would like to play the roles impeccably, but not get lost in them. To finish her, because that’s a good death to share with you, she said, “I see a young child in a tree, frightened, and a menacing man walking around the tree. I think it has something to do with my death, so I’ve been sending the man good vibrations.” I thought about that and I said, “It sounds like one of the first of the ten thousand horrible visions and ten thousand beautiful visions. If you sit around manipulating every one of them, you’re never going to die.” I mean the world does have menacing men and scared children. She says, “But I feel as if everything is pressing in on me.” So I went into that space. I said, “That’s an easy one. That’s because you are busy being a one-quart container where a gallon of water is being poured into you. Because as you start to let go of things you are, you tune into more and more energy. You try to fit that energy into who you thought you were, and it overloads.” I remember once I was sitting in front of Maharaji. He was sitting there, and then suddenly he lay over on his side and he started to snore. He wasn’t even lying down, he was just sort of on his side, snoring. And when he did that I was focusing on my third eye, figuring this time I’m not going to get sucked into all his talk and movement. I’m going for the inner guru. I’ll just use his juice. So, I’m sitting there focusing on my third eye, and I start to shake. I was shaking so badly I thought I was going to break my spine. It was like trying to ride a wild horse in the rodeo. At that point he sat up and he said, “Ask Ram Dass how much money Steven makes.” The fellow next to me said, “Well, Maharaji, he’s meditating.” “No. Wake him up, he’s not meditating.” And the guy shook me and asked, “How much money does Steven make?” And I heard it from way out, “How much money does Steven make?” Oh shit, well okay, “Thirty thousand dollars.” Then I tried to get back out, but then, of course, it’s all over. You can’t grab a memory. It’s like a dead butterfly. It doesn’t fly again. So I said to her, “The problem is that you’re being a one-quart container. Just expand. Include everything you can hear, smell, touch, taste, feel, or think about. Just go outward.” So, we closed our eyes, and I said, “Do you hear the clock ticking? Become the clock ticking. Tick, tick, tick. Hear the children on the street playing? Become the children. Allow it all within yourself.”

The paradox: it is all perfect and it all stinks. A conscious being lives simultaneously with both of those.

Feel this hall at this moment. Instead of being somebody sitting in the hall attached to all your sensations, expand outward until all of this hall is within you. Look down within yourself and see all of us sitting here involved with this drama. The Cambodians in the camps on the Thai border, inside us. It’s us. Keep expanding. How about the Earth? Can you experience the entire Earth within yourself? Just play. You look on the surface of the Earth, and there’s weather, and volcanic eruptions. There’s humans and struggles and violence and inhumanity and unfairness and changes. There’s floods and tidal waves. And here you are, present, quiet, peaceful, loving, understanding. This is the kind of peace that brings peace to the world, the peace of non-attachment. Keep going out until the entire universe is within you, galaxies, black holes. Everything you can conceive of within form is within you. You are the ancient one. No form, no limit, no time, no space. There is only one of us. You may get lonely if you’re busy with your separateness. If you start to experience loneliness, look again to see if it isn’t merely aloneness, the great aloneness, the great at-oneness, at-oneness, atonement. And rooted in this one you play the dance of the two.

A poem on the Norman Crucifix of 1632: “I am the great sun, but you do not see me. I am your husband, but you turn away. I am the captive, but you do not free me. I am the captain, you will not obey. I am the truth, but you will not believe me. I am the city, where you will not stay. I am your wife, your child, but you will leave me. I am that God to whom you will not pray. I am your council, but you do not hear me. I am the lover, whom you will betray. I am the victor, but you do not cheer me, I am the holy dove, whom you will slay. I am your life, but if you will not name me, seal up your soul with tears and never blame me.”

We are the One as the many, all of us. And every time we get lost in the many we use it as a vehicle to return to the One. And every time we enter the One we come back into the many to play, and we become impeccable warriors, at service, at love, at relationship, in politics and the arts — in a dance of living and dying. We dance through it, with involvement, but without clinging. As the Bhagavad Gita says, “We are not attached to being the actor, nor are we attached to the fruits of the action. And yet we act without seizing.” When you have become zero, when you have died into the One, when you are fully not my but thy will, oh Lord, then every act, every thought, recreates the universe. But then, who is to have thoughts that are separate from the law? For at that point there is only one of us left, and we created the dance in the first place. What an extraordinary thing, that you and I can meet on this plane to reflect about this. What extraordinary grace.

You and I chipped in tonight to help pay for THE SUN magazine. Why would I do a benefit for THE SUN? I mean of all the worthy causes, why would I do it for THE SUN? You know, it’s just another magazine. Well, it’s an interesting thing for you to ponder. All I can tell you is I am a subscriber. And a lover of the magazine and the beings that put it together, and how it comes together, and the way the spirit manifests through it. There are a lot of little seed things around the country that I just feel love for. THE SUN is another dance I feel good in my heart about. See, very often when we go on the spiritual journey we get kind of klutzy and heavy. I realized that I had to honor the totality, and one of the things was aesthetics. What happened to aesthetics? And I went back to playing the cello again, and I play in a trio with a harpsichord and a recorder. You’ve got to keep it all together.

I’m a part of something called the Seva Foundation Blindness Project, which is a group of people getting rid of unnecessary blindness. I was at the board meeting of the Seva Foundation, and there was an Indian doctor who told us that his mobile eye hospitals were performing operations in India on the kind of cataracts that grew in India because of the diet, and they could perform these operations in four minutes at a cost of five dollars. At this moment there are seven to nine million people who are blind in India, waiting for this operation. Many of them are going to wait the rest of their lives, and some of them are probably thirty or twenty, and they will never get the operation because there is no money or hospital. Five dollars, four minutes. Now, if those people who are blind are “them,” then you can use your next five bucks for whatever you want, but if it were your father, for example . . . “Hey, son, daughter, I’m blind, would you mind loaning me five dollars so that I can see again?” “Sorry, I’m going to the flicks.” So, we had the annual meeting last year. Larry, who heads the foundation — the doctor whose introduction to Maharaji I read to you — came up to me and he said, “I want you to meet this couple that’s given some money. Let them tell you this story.” The woman said, “We had set aside two thousand dollars to buy a hot tub, and then I heard one of your tapes in which you said for five dollars a person that was blind could see. And I thought to myself, “If I give up this hot tub, four hundred people could see. So, we sent you the two thousand dollars.” The reactions I had to that were both, “Oh wow, what an act, you’re a beautiful person,” and also, “Oh my God, does that mean I have to give up hot tubs?”

Over Gandhi’s tomb it says, “Think of the poorest person you have ever seen, and ask yourself whether your next act will be of any help to that person.” Maharaji said, “Be like Gandhi” to me. If I am going to live like Gandhi, I’ve got to keep that person there all the time as I live my life. Not only that, but I’ve got my guru, Maharaji, who is laughing himself sick over me. Every time I look at him he’s just giggling. So, I have this giggling fool and this poor person starving, looking into my eyes with those big eyes. And I’ve got to try and live my life? You know, you can’t even go the bathroom. It’s like two guys who are given two chickens and told to kill them where nobody can see, and one goes behind the barn and kills the chicken, and the other walks around for two days, and finally comes back and says, “I can’t find a place where the chicken won’t see.” If you really want to get free, you just have to remember, that’s all. And it’ll do it to you. It’s doing it to you anyway. You wouldn’t even be here tonight if it wasn’t. You don’t have to do anything. It’s all happening. It’s all happened, you’ve all been had. The Martian takeover is complete. You can go now.

In India when we meet and part we say, “Namaste,” which means, “I honor the place in you where, when you’re in yours and I’m in mine, there’s only one of us. I honor the place of God within you, of love within you, of peace, of presence.” Namaste.

After a break, Ram Dass answered questions. On our tape, some were unintelligible. Fortunately, he paraphrased most of them.

— Ed.

QUESTION: What’s the purpose of reason and intellect?

RAM DASS: It’s an exquisite instrument, just like prehensile ability, to control and master, or tune, or interact within certain planes of relative reality. It’s a sub-system. It’s a beautiful servant and a lousy master. The minute you are without thought, then you can think as a form of play. If you’re attached to your thought, then your thought is your enemy; it’s your prison. So, you extricate yourself from thought, in order to play with thought. You cannot understand God. You can only become God. You can’t know God with your intellect. But, you can go into that which is beyond intellect, and then come back in conceptualization, and describe the indescribable as best you can.

QUESTION: About mediums. . . .

RAM DASS: I’ve learned over the years that everybody that doesn’t have a body doesn’t necessarily know more than I know. What happens is, someone who’s a well-meaning pipe-fitter dies. They’re hanging around, very attached to the physical plane, not ready to get on with their other work. And they figure, I’ll do good for the physical plane, by talking to Uncle Sam, or Aunt Mathilda, and telling them how it is. But all they know is what they know, which isn’t much more. Then there are some very high beings that come through to this plane. You can take whatever you can get, and feel it with your heart. You’ve just got to trust your own heart as to what’s useful. Your method can be to use astral help, guides, spirit agents, gurus, all of that. These are all vehicles. You’ve got to go beyond vehicles finally. But don’t throw away the boat until you get across the river, or the ocean, as the case may be. So, if it’s useful, use it.

QUESTION: About LSD. . . .

RAM DASS: The first time I went to India I gave Maharaji 900 micrograms of pure acid, and nothing happened. That impressed me. Because I know that when you take 900 micrograms of acid, no matter how fat you are, something happens. So, I came back to America and I told everybody that nothing happened, but then I had the suspicion that he had sort of hypnotized me, and that he’d thrown them over his shoulder instead of into his mouth. I kept worrying about it. When I went back to India in 1971, he called to me, “Did you give me some medicine last time you were here?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “Did I take it?” I said, “I think so.” He said, “What happened?” I said, “Nothing.” He said, “Well, go away.” The next day he said, “Do you have any more of that?” I said, “Yeah.” So, I brought it out, and he took 1200 micrograms this time. And he took each one and stuck it on his tongue, and made sure I saw that he swallowed it. Then about halfway through the journey he went under his blanket, and he came up looking absolutely insane. I thought, “Oh my God, what have I done to this poor old man. He probably read my mind and he thought that I thought that he couldn’t take the acid and he took it. He didn’t realize how powerful it was, poor slob.” At the end of an hour he said, “You got anything stronger?” And obviously nothing had happened at all. Then he said, “It’s useful. It would allow you to come in and have the darshan of Christ,” meaning you could come in and be in the presence of the spirit. He said, “But you could only stay two hours and then you’d have to leave. It would be better to become Christ than to visit him, but your medicine won’t do that for you. Love is a stronger medicine than your medicine.” I really heard that. I heard that in a final analysis it wasn’t the true samadhi. It was a useful vehicle, but finally it wasn’t the whole vehicle. I said to him, “Should I take that medicine anymore?” He said, “Yes, if you’re in a cool place, you’re feeling much peace, you’re alone and your mind is turned toward God, it could be useful.” And I have used it that way about every two years. The last three times were in San Francisco, Bali and the Mid-America Hotel in Salina, Kansas. And every one of them has been incredibly useful and beautiful. I learned a great deal and honor it. I also know that I don’t care if I ever take it again. And I may take it next week. I have no more rules about the games of life. I just listen to my heart. I trust my heart. People say, “Do you take drugs? You don’t take drugs, do you?” or, “Do you have sex?” And I say, “I don’t have any rules. I don’t have any definitions. I’m just open to what is.”

QUESTION: About the effects of LSD. . . .

RAM DASS: What kind of effect did it have? I think it had an incredible effect in breaking me out of a kind of reality that I was locked into. It put it into relative reality. I think my first experience with psilocybin did that. And whether or not that would have happened anyway, who knows? You don’t have any control over the experiment. It seemed very useful to me at the time. I’ve learned over time, as I stand back, that things that seemed like critical events usually aren’t. They were critical because you were ready for them. And that has to do with where you were at. Obviously a lot of people have taken psychedelics who don’t seem to have awakened much through them. Just the drug itself doesn’t do it if your model or your karma is too thick. And I think when your karma gets thin enough a leaf falling off a tree could do it. It well may be that what we needed to blow our brains out with in the 60’s is now anachronistic because the relative realities that we did it to overcome are now accepted parts of the culture.

QUESTION: About dying. . . .

RAM DASS: What has been useful with people that are dying is your work on yourself. You stay so centered and present and loving and uncaught in the whole issue of living and dying that you are right there for that person, so they can get free of the melodrama of dying to be with you in pure awareness. And all you can offer them is your being. Everything you’ve done and all of your work on yourself is what you offer. And there’s no rule of “Do this. Do that.” It isn’t that way at all. It’s be. Be fully present. Be with the death and the life and the healing, whichever way it goes, because you don’t know how it’s supposed to go. You don’t know whether the person is supposed to live or die. There’s a great story of Maharaji’s in which he says, “Somebody’s coming.” And they say, “No, nobody’s coming.” He says, “Yes, somebody’s coming.” And just then a servant of one of his devotees comes in and Maharaji yells at him, “I know your boss just had a heart attack and he’s calling for me, but I’m not going to go.” He says, “But he’s dying, Maharaji.” “I know, but I’m not going to go.” And everybody says, “Ah, but he’s been a devotee for so many years. Go, Maharaji.” “No. I’m not going to go.” Finally he picks up a banana. He says, “Here. Give him this. He’ll be all right.” In India, if the guru gives a piece of fruit. . . . If you’re a ninety-year-old lady and you want to have a baby, you go to the guru and you say, “I want to have a baby.” He says, “Here, eat this mango.” And nine months later you have a baby. So they took the banana home and they mashed it up and they fed it to him and he took the last bite and he died. That’s the end of the story. All Maharaji said was, “He’ll be all right.” He didn’t say how.

QUESTION: About love. . . .

RAM DASS: Once you start to tune in to love, then you could fall in love with everybody, continually, all the time. And obviously, you have to change your way of reacting to that experience. As you quiet down, you begin to see that there are various vehicles for awakening, and you’ve got to listen to find out what your vehicle is. Your vehicle may be just taking experiences as they come, letting them go, whatever comes your way, and letting go lightly all the time. That would be a method. Your vehicle may be renunciation. Going to the mountains. That’s a method. There are thousands of methods. Service is a method. The method that you may hear might be that of working with a partner to go from the two into the One. That may be a method. I have my method. My method is my guru. I’m not looking around for a method. I do what I have to do. My service is part of my method to my guru. Once something starts to work for you and you begin to see it as a method, you lose interest in collecting more because it’s just going to complicate the whole stew. And you make decisions: “I could love you. I could fall in love. We could run away. I feel passion. I feel all this stuff, but it isn’t in the karmic cards because I’m already at work and it’s fine, and I love you and I wish you well.” Do you hear that one? Sometimes, of course, the grass is greener on the other side. Familiarity turns off the mystery of the romanticism, of the unknown, and you’re suddenly dealing with all of these fascinations. But, they are just fascinations, and if you keep pursuing them all it’s as if you keep digging shallow wells and you never get the water because you don’t go deep enough. There is a quality when you get to hate your partner, and you’re turned off, and you never want to see them again, and all that, when it really starts to happen. A marriage, a relationship — if it is living truth — it’s right on the line between cosmos and chaos all the time. The minute it gets too smooth, forget it. You’re probably sleepwalking through it. “Oh, we’re so happy. I love you, you love me. I know who you are. . . .” Forget it. Because, each of us is changing all the time. As Mahatma Gandhi said, “God is absolute truth. I am only relative truth.” As a human being, I see a new truth each day. The commitment is to truth, not to consistency. A relationship that can withstand the changing truths really goes deep. It is an absolutely incredible vehicle. But it is a very consuming vehicle. You can’t put it on the back burner and go do something else. It really takes a lot of juice.

You find the method that is harmonious with your vehicle and you work with it. So, if you have a physical illness, that’s the method. If you have a child, that’s the method. If you have an old father, that’s the method. If have a brilliant intellect, that’s the method. If you’ve got a big heart, that’s your method. You keep working with your methods.

QUESTION: What role does somebody who is physically disabled play in the spiritual growth of others, and what is happening for them?

RAM DASS: I don’t think that I can answer more specifically than that we are each other’s karma. When you are with somebody that is disabled, very often this gives you a chance to see your own attachments and fears and particular lifestyle. If you get over seeing one is better than another and just see it as different, the whole game looks different to you. People come to me all bent over with arthritis, in pain, taking a hundred aspirin a day. All I say to them is, “Heavy round this time, isn’t it? Heavy work to do.” My job is to love and be with the person, not to judge it or anything. Just to honor it and to open to it. I don’t know that that isn’t the best thing for the person. I don’t have to judge God. I just have to be with it. I can feel the functional nature of suffering for people. We wouldn’t lay it on each other, we wouldn’t ask for it ourselves, but a conscious being uses it. When you are conscious, you are able to see suffering that way, and you create an environment in which someone who is suffering can see themselves that way if they are ready to see it. There’s nothing in you that doesn’t allow them to get out of the trap of being somebody suffering. So, when you’re working with somebody that is disabled, who is caught in being disabled, your job is not to get lost. With dying people, they’re dying at one level. At another level, you’re here. I’m here. Here we are. “What’s new today?” “Well, I’m dying.” “That’s interesting. What else is new?”

QUESTION: What is the most easily confused aspect of sexual responsibility?

RAM DASS: The identification with your own sexuality. Sexuality is part of your being, it is not who you are. The overidentification with it means that you polarize the universe and get into identifying as a relater, rather than that which is the totality. It catches you in the roles, and thus, makes the whole thing dualistic. It comes down to Freudian sexuality, or lust, or subject-object sexuality. The error is getting caught in subject-object, which is merely projecting outward an object to gratify you sexually. Sexual tantra starts from a place of us. It never loses the us, so the sexual arousal doesn’t come out of seeing the other person as an object. It a doesn’t come out of a fantasy projection. It comes out of a natural flow of being together. That’s why I usually say to people, only have sex with your friends. And Maharaji said, “Your only friend is God.” So, finally, you will only have sex with God. You come to the place where it’s us, and out of the us-ness sexuality happens naturally. The problem is, that mechanism is so over-learned, it catches you so strongly, that the minute the arousal mechanism starts, you’re busily being a person who has sexual desire or need or being a sexual actor. You get caught in the act in those two levels. And the minute you get caught in the act, you just lost it. Because then the act can only give pleasure, it cannot give liberation. If an act only gives pleasure and not liberation, it increases your karma, it doesn’t decrease your karma. There’s a way to use sexuality to go beyond sexuality. Or there’s a way to use sexuality to stay in it. And most people use sexuality to stay in it, by wanting the rush that comes from identifying with the sexual experience, rather than using it as a vehicle to open, all the time.

QUESTION: About being treated as a sexual object. . . .

RAM DASS: When you feel you’re being regarded as a sexual object finally you have compassion for the person who’s doing that. Because you know who you are. If somebody hates me, I figure that’s their problem; I’m a really beautiful guy. As long as you are using somebody else to tell you who you are, if they see you as a sexual object, that’s who you buy. When you finally realize who you are — I am, but I’m also that — all you have to do is love them, you don’t have to change them. Loving another person is the optimum condition where if they want to let go they can let go, and if not, they see you as an object, and that’s just another dance. But you don’t buy another person’s mind.

QUESTION: About gurus. . . .

RAM DASS: All methods are traps. A guru is dualistic, just as God in form is dualistic, as something or somebody outside, and you use dualistic methods to open your heart, to learn, to listen, until finally you merge. You go through the guru and into yourself and then the guru disappears and you come out the other end. You use the method until it self-destructs. At one point, I was sitting opposite Maharaji in the courtyard and everybody was rubbing his feet and talking to him and I thought, “Why are they all doing that? I’m not going to spend the rest of my life rubbing this old man’s feet. That couldn’t be my way to God. This is absurd. I don’t care if I never see him again.” And then I thought, “Gee, this is heresy. I love him so much. How could I not care if I never see him again?” And just as I had that thought, he turned quickly and looked at me and he whispered to this old man, who came running across and touched my feet, which was weird. And I said, “Baba, why did you touch my feet?” And he said, “Maharaji said, ‘Go touch Ram Dass’ feet. He and I understand each other perfectly.’ ” And what I heard him saying was, “Don’t get hung up on this. You’re absolutely right on. Use it, and then let it go.” And I really feel that. I’m not a guru and I’m not an enlightened being. I’m just somebody on the path, but lest that get confused, I find it really nice to have no students, no ashram, no nothing. I’m just a wandering Jew. I’m just floating around, just growing in the nice soil, here and there.

QUESTION: About spiritual hazards. . . .

RAM DASS: Spiritual occupational hazards, for instance my occupational hazards. What do you do when someone comes up and looks at you as if you are the Light and their doorway through? Oh, Ram Dass! The occupational hazard is that you’ll get caught in thinking that you are who they think you are. In other words, how do you deal with fame, how do you deal with the projections, how do you deal with something coming through you? Do you think it’s you? Do you get caught in it? Where does your ego buy in? How do you deal with power, because fame is power. And money is power, all this stuff is power. How do you deal with power? Is it your power? Or do you realize you’re like a bookkeeper for the firm and your job is merely to be used as dharmically as you know how. Once you have fame you can gratify yourself much more easily and then you’ve got to see whether your acts of gratification limit the freedom of another human being. And this would be a misuse of your powers. I don’t even see the power anymore. It’s just irrelevant. I look at myself as just like you. We’re all just here together. I’m just playing my part. I’m no longer identified with the part. It’s a Rent-A-Ram Dass. It’s much lighter. There are other kinds of hazards of getting caught in spiritual materialism, or getting caught in spiritual myths about who I am. Maharaji used to set me up all the time. He’d say, “Ram Dass is your guru. Follow Ram Dass.” And then he’d make a total fool out of me in front of everybody. He’d set me up and then knock me down, and set me up and knock me down. It was great. He was just helping me through.

QUESTION: About grieving. . . .