Years ago, in New York City, I had a friend named Tom (Tommy Tapes, they called him, because he carried his eight-tracks everywhere), who looked like Mick Jagger and lived with an intensity that was vital and fearful, like New York itself.

I was on the verge of quitting my last newspaper job, and he gave me a friendly push, over the edge. Music was important to him because it emerged, and disappeared, from that living darkness that lay just beyond. He drove towards it, and over some edge in himself. The last time I spoke with him, his voice on the phone murmured apologetically about a “nervous breakdown.” He was a dark fish swimming away from me, in black waters, a black so unpenetrable and so different from the hot black of his eyes that fixed me one day as we were listening to a song. “Don’t tap your foot,” he said. “Listen to the words.”

Don’t tap your foot. Listen to the words. If I was to be marooned on a South Sea Island with a half dozen metaphors, that would be one. It’s as elastic as a new pair of underwear, and snugly fits the times. Marooned last month in California, at the Whole Earth Jamboree, I listened. In California, the beat is compelling. It’s a state, and a state of mind, where everything seems possible, where the dreams of an age sink down roots, and grow, as dramatically as Findhorn’s 40-pound cabbages, yet may die before their seeds are carried “in from the coast.” Reflecting the best and worst in ourselves, it’s still the frontier, ever receding; the deeper we go into ourselves, the more there is to discover.

The Whole Earth Jamboree was organized by the people who started the Whole Earth Catalog ten years ago, to celebrate a decade of counter-cultural cross-breeding and mutation. The Catalog was itself the incentive for much of that change; at that busy intersection where all roads converged — appropriate technology, community, spirituality — the Catalog stood like a traffic cop. Nobody could understand everything that was happening, but the Catalog (with sections like “Understanding Whole Systems”) tried. It was the working manual of the alternative society, an access to “tools” (from books to solar collectors) to help people get out of the city. And it was the best journalism about that movement. Brassy (“We are as gods and might as well get good at it,” the first issue proclaimed) and tight (editor Stewart Brand’s mini-reviews were an art form in themselves), the Catalog was a bridge, between the early romanticism of the back-to-the-land movement and the more seasoned understanding that followed a few failures — not just with the land, but with people. It was easy to confuse being different with being better, to mistake lifestyle for living a life; if we are as gods, that means everyone, not just those who build windmills and eat natural foods. The Catalog reflected a generation’s deepening comprehension of that truth, even as it sometimes ignored it.

In 1974, the Catalog was reborn as the CoEvolution Quarterly. Sort of a Catalog plus, the CQ, in addition to reviews and access to tools, prints a wide range of thoughtful articles. “I print what looks interesting,” Brand says. “We’re an idea magazine, and ideas are loose on the West Coast.”

Loose enough for Brand to enlist not only the Park Service but the National Guard to help with the Jamboree, which was held in the Golden Gate National Recreation area, just north of San Francisco, during the last weekend in August.

There was to be something for everyone: New Games (the “non-competitive” sports conceived by the Whole Earth crowd in 1972); music; booths of environmentally-oriented businesses; a talk stage. The speakers — including poets Allen Ginsberg and Michael McClure, architect Paolo Soleri, writers William Irwin Thompson and George Leonard, and dozens of lesser-known contributors to the Catalog and the CQ — were the main draw, for the public and for each other. Brand’s idea was to get together some of the “remarkable” people with whom the Catalog and the CQ had dealings over the years. “The idea,” his invitation said, “is to have an encampment, a tent city, for all of you to inhabit for the weekend, Friday through Sunday. I learned the power of this kind of gathering at Steve Baer’s conference called ‘Alloy’ in 1969. We outlaw designers met for three days at an abandoned tile factory near the first atom bomb test site at Alamogordo, New Mexico and were never the same afterward.”

Nobody was paid to come, but shelter and food and local transport were promised. The speakers were asked to make a five-minute statement — “anything . . . your latest work, a ukulele number, capsule philosophy, dazzling riposte, inspiring silence, a string of jokes. Only . . . it can’t be praise of the Whole Earth or CQ or the Jamboree (bound to be boring).”

Why was I invited? I didn’t know. All I could figure was that somebody liked THE SUN; the CQ had subscribed a year earlier and recently published some of my stories. Still, it was easy to imagine that, in their eyes, North Carolina was an intellectual and cultural backwater. And, in comparison to the other speakers (most of them from the West Coast, and more hip, or “established,” than I), I felt like a stutterer, my body of ideas scrawny and pale. Did I want to parade it for five minutes before thousands of people? Besides, I’m afraid of flying. And, finally, I was put off by Brand. I’d called to thank him, and ask for advice about THE SUN. “I believe in destroying magazines, not saving them,” he said. If a magazine wasn’t self-supporting, he went on, it didn’t deserve to continue. I laughed, nervously, as if I agreed, but his answer seemed thoughtless; at least it wasn’t compassionate. Every magazine, unless it’s generously bankrolled (like the CQ, with Whole Earth profits) struggles to become self-supporting. I expected more than this gem of Social Darwinism.

Still, there were good reasons to go. My respect for Brand and the CQ is enormous; I think it’s the best magazine in the country. And I didn’t want to pass up the chance to be exposed to new ideas and new faces, to glimpse the Pacific again, and to bring back news of what was stirring among those on the cutting edge of cultural change.

I survived the flight. (Palms sweaty, teeth clenched during take-off, finally turning to the man beside me to say, “Hey, I’m nervous. Would you please talk to me? I’m chickenshit about flying,” and his face breaking into a wide grin, shooting back, “Nervous, man? You know what I do? I’m a paratrooper. I jump from these things.”) I was picked up at the airport by a friend who drove me to Santa Cruz, where we stayed all night talking. I hitched back to San Francisco the next day, the Pacific on my right, the wind like a wild mother. Such beauty! I scribbled in my notebook: “The Santa Cruz scene. Felt like I was in a movie about California, and these were the extras. How shallow it seems, this flowering of the ‘dream.’ It was its edginess that made the beat and hip life so powerful. What got confused was the style for the content. At least that’s what got marketed: boutiques, coffee houses, cafes of rough oak and smoked glass and all the other wet-dreams. They’ve got nothing to do with freedom or creativity or love. This isn’t it, you schmucks! And the worst part is, you imagine you’re more liberated than the truck drivers and the housewives. . . . Oh Sy, stop scolding. You moralist. You rabbi. Everybody’s smiling, the sun is shining, put your black suit in a box and float it out to sea.”

The Jamboree site was a lovely valley between gently rounded hilltops; the speaker encampment was in another valley, about a five-minute ride away. The encampment was a disappointment. I’d envisioned large tents with bunks, showers — primitive, but comfortable. It was primitive, at least. We put up our own tents, old Army shelter halves with no ground covers. No showers, either. But the food was good.

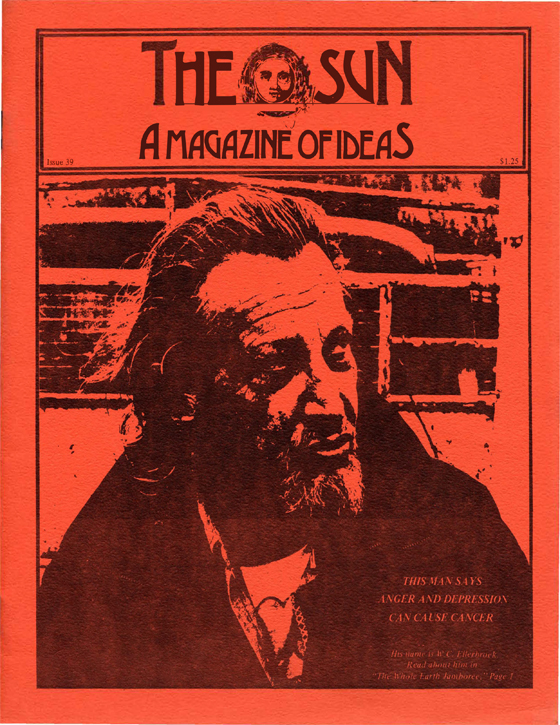

The first person I met, who left the most lasting impression on me, was W.C. Ellerbroek. I didn’t know what to make of him. His shirt was embroidered with the word Magic, and a spider, and God-knows-what-else. His goatee and wrinkled face emphasized the Mephistophalean aura. I wanted to steer clear; I’m glad I didn’t.

Ellerbroek was a surgeon for 19 years before becoming a psychiatrist (he works at Metropolitan State Hospital in Los Angeles; you can write him at Box 367, Sunset Beach, CA 90742). He’s thought alot about disease in general and cancer in particular. His conclusion? That what’s responsible for cancer is anger and depression.

Does that make you sigh? Sighing, says Ellerbroek, is what people do when they’ve given up the right to feel hostile and angry.

Ellerbroek wrote an article called “Language, Thought, and Disease.” It took seven years to get it published in a scientific journal (the CQ reprinted it in Spring 1978). It was, ostensibly, about acne, not cancer; if it had been about cancer, he says, it never would have been published. “For those who can read between the lines,” he says, “it will tell you how to keep yourself from getting cancer, or, if you have it, how to contribute to your own recovery.”

The same mechanisms, Ellerbroek writes, are responsible for physical and so-called mental illnesses; anger and depression are “pathological,” their effect upon us trivial or catastrophic. We can give up anger and depression once we better understand how our minds work, and how language reflects the errors in our understanding (and leads to additional errors).

We “create” conflict by insisting that reality match our fantasy about how things should be. Since reality rarely accommodates our fantasies, we become frustrated and unhappy (and, insofar as these “negative” reactions are, in every instance, harmful to ourselves, we get sick). What we forget is that we have only a partial view of “reality,” and can never fully comprehend the fantastic complexity of another human being or a particular event. Example:

“Pretend for a moment that today your wife has torn off one of the garage doors; if you repeatedly say, in an appropriate tone, ‘She shouldn’t have done that,’ you will become aware of increasing tension and anger. Conversely, if you then say, ‘Considering everything I know about my wife, and bearing in mind that there are many factors of which I am unaware, since the event has already occurred, it is obvious that today is the day my wife should have torn off the garage door!’ you will notice a prompt, definitive decrease in your unpleasant emotion, as well as a simultaneous correction of the rise in your gastric acidity, serum free fatty acids, and cholesterol. The first statement is contrary to reality; the second is in strict accord with reality.” Nothing about this, Ellerbroek adds, means you should be pleased about the accident, nor try to keep it from happening again.

In treating acne patients, he urged them, when looking at the mirror, to say to themselves this is how they should look today; his idea was that wishing away the lesions is useless. Until patients realized the acne was a response to feeling picked on, the lesions stayed. Without the picked on feeling, patients no longer picked on themselves and lesions disappeared.

I asked Ellerbroek about his own upbringing. He said he saw his parents and grandparents as “part of the chain of the whole catastrophe. As civilization developed we’ve gotten more and more screwed up.” He paused, then added, “I escaped.”

“How?” I asked.

“When I was very small,” he said, “I never believed anything.”

Two tents away: William Irwin Thompson, cultural historian, New Age theoretician, author of At The Edge of History and other books, co-founder of the Lindisfarne community in New York.

I got right to the point. I stumble over the phrase “New Age,” I told him. It tells me less about real change than it does about the prejudices of those who use it, unthinkingly, as a label.

“You should stumble over it,” he replied. It’s an “inflationary term,” like Findhorn’s description of itself as a light center. Most people don’t understand what the New Age means, he went on. “If you listen to the hype about the New Age you imagine we’re moving toward a more liberated lifestyle, but if you read the newspapers you understand something else is happening.” We’re only at the beginning of the New Age, anyway; things will “get worse before they get better,” and that won’t be before the year 2600.

Thompson smiled only once during our half-hour of conversation — and not at me, but at his daughter.

He was unhappy camping. “This is the first time I’ve done it, and it’s the last. When I travel, I like to go first class.”

A shuttle bus carried us to the admission gate, where we flashed our “I pass” buttons to get in; the public paid $3 a day. The weather was good, the atmosphere festive. There was a juggler, a puppet show. Booths to save the whales, the forests, the rivers, information about every facet of environmentalism, good people behind good causes, and I dutifully listened, and got bored.

The truth is, I don’t care much about windmills and solar collectors. It’s important to love the earth, to be energy conscious and politically aware. But appropriate technology and environmentalism and the anti-nuke movement take us only so far — to the threshold of ourselves. They don’t tell us how to love ourselves. And if we don’t know that, if we’re afraid of our own beauty, it becomes easy to hide, to say look at my windmill rather than look at me. A heart filled with hate sets off chain reactions no less deadly than a runaway reactor. Nothing is served by turning the world into a movie where good guys slug it out with bad guys. It’s our own habits of thought that make it seem that way — our own ambition and competitiveness. Even when we say small is beautiful we’re usually talking about more small or my small is better than your small. Is there an energy crisis? Sure. But isn’t it also true that the whole universe is energy, and that we have within ourselves all the energy we need? It has nothing to do with whether we eat steak or sunflower seeds or how we dress or how many asanas we do. We are gods, creating our world with our beliefs, our shoulds and shouldn’ts, the light of the sun and the light of our love.

The smell of the valley, and the ground I slept on, stayed on my clothes for days after I returned. These memories linger, too:

Brand, on Friday night, calling us together to line up speaker schedules for the next two days. Wearing a brown leather flight jacket, he apologizes for sounding like a lieutenant.

my, the journalist who goes by his initials, talking, over coffee, about the value of skepticism, saying that “in the New Age everyone knows everything and skepticism becomes confused with cynicism.”

Stanley Marsh III, the art patron and TV station owner from Texas, making a lovingly preposterous speech about how we should all be special. “To demonstrate that I’ve brought this wretched little animal with me, a Chinese hairless dog. Now if this dog had not had these wings tattooed on its side he’d probably be in a bowl of chop suey today. But being the fact that he’s the only winged dog in the world he lives here on the stage right now. . . .”

Peter Orlovsky, the poet, screaming into the microphone for all of us to “give a shit”: “even cows don’t throw away their plop / but let it drop / near many eating pasture spots / and next year dung turns into better green / grass than before . . .”

Allen Ginsberg, introduced by Brand as an American saint, powerfully intoning his “Plutonian Ode”: “I enter your secret places with my mind, I enter with your Presence / I roar your Lion roar with mortal mouth! One atom to one lung, one pound to earth your radiance is speed’s blight and death to all sentient beings . . .”

J. Baldwin, CQ soft technology editor, drawing cheers when he urges the crowd to “demonstrate our ability to do something right, on an irrefutable scale” — build a solar-powered city for 35,000 people.

Michael McClure, poet and playwright: “It is the same old politics. Any politics is the politics of extinction.” The politics of the caveman was to kill large mammals, “ours is the eradication of the substrate itself.” Urging us “out of the closet of the politics” and “into the light of our flesh and our bodies.”

Fifty-seven speakers. Too much eloquence affecting the mind like too much dope. Is it dope, the way we describe ourselves to ourselves? It can be, and some of it was: the braying of an animal that the most fearful would place at the top of the endangered species list. But much of what was said at the Jamboree was hopeful — an affirmation of man’s ability to learn and grow, to stop mindlessly tapping our feet, to the beat of progress, or apocalypse, and listen.

Below, some of the more thoughtful statements. The next issue of the CQ will publish most of what was said. The address of the CQ is Box 428, Sausalito, Ca 94965; subscriptions are $12 a year, and you ought to subscribe, since the Whole Earth money is about gone and the CQ is not yet self-sustaining. I believe in saving magazines.

The five-minute rule was strictly enforced. At the end of five minutes a buzzer went off; fifteen seconds later the microphone went dead. (Sam Keen got caught after reading 39 of his 44 New Age propositions). Some of these statements have been edited because of space limitations.

George Leonard

I’d like to start by saying we can’t really talk about the future. It’s mostly myth, facts will always elude us, the general shape remains unclear, it’s never going to stand still for a snapshot even if the camera is the biggest computer that you could possibly build. I’d like to propose, in fact, that the only justification for what we call future studies is that by forcing us to change our perspective, they allow us more clearly and accurately to view the present, which otherwise is too close to our noses for us to make any sense out of it. I’d like to further propose that when we do see the present, we find out that our culture is already involved in a vast, meta-historical transformation, a transformation in how we deal with matter and energy, how we organize society, and how we shape consciousness itself. We are engaged in a game, in which the score always seems to be tied, and it always seems to be the last two minutes to play. To avoid a catastrophic loss, we’ve got to somehow, as unlikely as it might seem, shift our game plan from emphasis on ever increasing consumption and depletion of natural resources, to the greatest possible development of human resources. And the question is, if this is a game, what’s the purpose of the game? What is the intention of the universe? Harvard astronomer David Lazer has pointed out that the universe is indeed unfolding in time, but not unraveling; it is becoming continually richer and more complex in information. Lazer points out that even if you could hook up the whole universe, as a computer, it would not be able to specify its own future state. There is new information constantly entering the picture. The present moment indeed contains an element of surprise, of genuine novelty. Now this increase in complexity and richness of information, this is the basis of our existence.

Thus our underlying story, our universal myth, is indeed evolution of a higher order. This doesn’t proceed in a straight line, but in waves, just like everything else. In some places, at some times, the evolution is backwards. But the dominant direction is quite clear, the intention of the universe is evolution, the evolution of higher forms, higher orders, not only of society but of consciousness. And ultimately, none of us can avoid this adventure. We’re all engaged, which brings us back to 1968. Remember the line on the first cover of the first Whole Earth Catalog: “We are as gods, and we might as well get good at it.”

Okay, we can’t see the future, we can’t predict the final score of the game, but we can know why we are playing. We are playing to create new order on the field of entropy, to transform ourselves, if only a little bit, and thus to add to the universal transformation. To become engaged, not apart from, the adventure of social and political and cultural change, an adventure which in light of our current difficulties makes the winning of the West seem pale by comparison. . . .

Back on Madison Avenue, there’s a cynical saying among some media people — “Yeah, what you’ve got is great, very artistic, but will Mrs. Murphy in Iowa understand it?” Well, I’ve given energy awareness workshops to high school counselors in Iowa, in little towns, I’ve given them in Nebraska, every place you can think of . . . and I can say for sure that the average high school counselor in Iowa is a lot more sophisticated about the tools and the purpose of this transformation than is the average editor in New York City. If there is a silent majority in the United States today, it is the silent majority for transformation. And I’ll say that we have to lay it out there. So I ask all of you, let’s never get discouraged, let’s help it happen, let’s give it voice.

George Leonard is the author of The Ultimate Athlete and other books. He is a teacher of aikido, the martial art of energy flow.

Witold Rybczynski

I’d like to talk to you today about slum Cadillacs and technological incongruity. In the 50s it was quite fashionable to study slums and the people who lived in them. One of the startling facts that came out of those studies was that a lot of poor people drive Cadillacs. What’s interesting is the kind of reaction that people gave to this fact. Some people were upset because they had Cadillacs and this somehow reduced their status symbol, but a lot of people were upset because they saw that this was somehow inefficient, and in some vague way, immoral.

This kind of philosophy has colored American thinking about technology for some time and that is that technological development must be congruent, everything has to move across the board on a step-by-step basis. According to this thinking, a poor person should drive a poor car. And a poor person driving an expensive car has this touch of immorality. I think that this is not a useful type of philosophy to have, even though it touches Buck Rogers type technologies as well as appropriate technologies. It’s not a useful thing, and I think that by looking at other cultures, we can see that it’s not an inevitable thing either.

I was doing some work once for an Indian band in northern Canada in a small village of about 500 people. There are many examples here of technological incongruities. The [Indians] are mainly trappers and they take long trips in the forest in the winter, where they rely on ageless woodcraft for survival. At the same time, they charter planes to get to their trap lines, rather than spending a lot of valuable time slogging through the bush.

The houses of these people have very little of what you would consider amenities — no running water, very simple methods of heating and cooking. They have no electricity but most of the houses have small cheap portable radios. They have no running water but most houses have washing machines standing outside, powered by gas motors. Some people even have small Honda generators they’ll crank up from time to time to watch color television by satellite. You might say, “Well this is just another example of white man’s technology taking over.” Well that’s not true, at least I don’t think it’s true. It seems to me that the Indians in this case are not hung up on this question of technological incongruities. They can put old and new things together. They’re not afraid to do that, and they’re not afraid to choose which things they want to put together.

Another brief example, from the Philippines. I was invited to give a talk in a squatter settlement, and I wanted to show some slides to some students. About ten minutes before this talk, there was still no slide projector, so I assumed that I’d have to give a talk and we’d forget about the slides. I was quite wrong because my friend who ran this school said, “Well, a slide projector isn’t that complicated, it’s just a lamp and a lens. I’ll just make one.” This is, I think, to the modern American, a flabbergasting reaction. If your shoelace breaks, you look for a piece of string, but if any of our modern technology goes wrong we just throw up our hands. The reason I think this person could react in such a sensible way is that his life was full of technological incongruities, he wasn’t a slave to the technology, he wasn’t afraid of it. So, when people tell you that you have to choose, one or the other, I would be very suspicious of that. I think that, in fact, we have to choose both and only by evolving both, side by side, do we get a healthier reaction to either. I could leave you with just one thought: wouldn’t it be surprising if the first Chinese astronaut used an abacus? Thank you.

Witold Rybczynski is one of the founding fathers of the appropriate technology movement. He teaches at McGill University in Montreal.

William Irwin Thompson

It’s absurd to talk in five minutes, so I’m going to try to be even more absurd and give a mini-lecture on one edge of history to the other in four and a half minutes. I want to talk about cultural change: where we got started, symbolization and the origins of art, notation in the upper paleolithic, agriculturization, civilization, industrialization, and the one we’re in now, planetization. The first one should be called the feminization of the primates because it all started when we got kicked out of the forest and the Pleiocene. We got so scared being open to the wild . . . that the women wanted to lure the males back, and so they threw away estrus and the heat system and went into sexual receptivity at all times which drew the men around them in small groups . . . and created the basic division of labor in which women gathered and attuned to plants, and men scrounged around and later learned how to hunt. So the origins of human culture come from women.

The women did it again then in the next big change, in symbolization, which really split and created the unconscious because language began to emerge, and it began like an island rising out of the sea to create the division between consciousness and the unconscious. And the basic relationship of those two was discovered by women in the synchronicity between their menstrual cycle and the lunar cycle, and so they were the first to observe periodicity and notation and create the origins of mathematics [with] little . . . sticks by which they kept the tag of ten lunar months for the duration of pregnancy. So the roots of science, . . . are with women. And it’s the Great Mother and not the Great Father holding his phallic wand that was making those sticks.

The next basic change again came from women, when through gathering, they began to interact with the system and collect wild grasses, and found that they could produce more food in three weeks than men could kill all year long and that therefore they’d better settle down and not go running around in the woods. And that created the neolithic village and the rise of agriculture. . . .

But unfortunately, it gave us enough of a surplus that we could shift to raiding bands and create warfare, so the surplus enabled us to try out some new things. Men responded by creating warfare as a response to woman’s creation of agriculture. So what happened there was that women got domesticated in civilization, and the Sumerian goddess comes to the male goddess and says “I, the woman, where are my prerogatives?” And [he answers] “. . . women are housewives and cooks, but men are chefs.” So the basic revolution of consciousness was civilization and the triumph of militaristic male, patriarchal organizational gods, which created, in a sense, the domestication of women, as women had domesticated plants, and as men had domesticated animals.

All the civilizations in the world had been based upon agriculture, and agrarian, until the industrial revolution, when finally, there was a new momentum, and now, industrial technology began to surround nature and turn it into a park. You saw this in 1851 in London with the Crystal Palace, where the trees were not cut down, they had a fair and display much like this, and they celebrated rose-decorated sewing machines, little vines growing up the legs, and had a whole false, medieval, romantic, nostalgic consciousness disguising the industrial structure. So industrialization was, in a sense, absorbing nature, and turning it into a park.

This was continued, in the next change, planetization, in which the Whole Earth Catalog — sorry, I’m being negative — took all of human culture and turned it into a collage, compressed it, miniaturized it, turned it into a park, and basically trashed it, in a way, so that everything became an object for consumption. It was disguised, false romanticism. People thought, like those rose-decorated sewing machines, that they were really grooving on stoneware pots and solar collectors and woodstoves, but what it was doing was miniaturizing all human culture and surrounding it with an invisible culture which became much more external when the CoEvolution Quarterly really extended that into space colonies, which turns all nature into a potted plant in a steel can. The internalization is dramatically expressed by CQ; there is not a distinction between space colonies and the back to nature movement. The back to nature movement is a nostalgic romanticism which is camoflauge for industrialization and high technology.

The other thing that is going on now that is much more invisible is the evolution of a new level of consciousness which turns the intellect into a park and makes out of the mind a mind dance. As we return to the Word, we’re going to see the dollar sign turned on its side, and the bars that crossed it melt, and turn it into a sign for an infinity.

William Irwin Thompson is the author of Passages About Earth, At The Edge of History and other books. He is co-founder of the Lindisfarne community in New York.

Paolo Soleri

My prime hypothesis is that reality is attempting to create its own sentience. This flips over theological thinking, head to foot. That which religion sees as the beginning, the seed, the divine power, we see instead as the end. Cosmogenesis, as the word says, is the creation of genes, the genus of the cosmos. I’m not giving you the truth. I am presenting a hypothesis. According to that hypothesis, the truth does not exist. It is in the process of being created. So it is for perfection, justice, beauty, grace, and so on. The embryo-like stage in which they are at present well explains the existence of sufferance, injustice, squalor, disgrace, ugliness. The human existential dilemma is the discrepancy between anticipation and the context in which we act and live. We dream of perfection, we get imperfection. We dream of justice and we get injustice, and so on. The amount of truth represented by the past is known to us in very tiny doses, but what is even more distressing is that the bulk of truth does not exist yet because it is stored in that which doesn’t exist, the future. Anguish is in the nature of life — to know that we do not know and to know that we cannot know. If we have access to knowing, creation would stop, time would stop, life would be put out. The truth which exists in time will be consumed, when the cosmogenesis is concluded. When the cosmos will have created its own seed, the seed will be a resurrection. That’s the gist of my hypothesis.

What we are trying to do in building this small town in Arizona is to be coherent with the hypothesis, so as to add . . . to the construction and creation of the ultimate seed. We are pursuing the urban effect as the most comprehensive process by which truth, justice, coherence, beauty, can be sought. The reason is simple. Cosmogenesis is . . . beyond the capacity of our imagination, and the urban mode is the prototypical structure capable of containing it. The urban effect is not a human invention, it is instead the very common way by which life goes about existing, persisting, reproducing, and evolving. Evolution is the urban effect imposed by life on non-life, by the exception which is life, or the rule which is no life. . . . We are trying to establish a better environmental coherence, a better use of resources, including the resources of the sun, we try to reduce the isolation and the segregation, and we are battling . . . a society hell-bent on consumerism . . .

Paolo Soleri lives in Scottsdale, Arizona where he is building a community called Arcosanti, a self-contained urban environment integrating the best of city and country living.

Sam Keen

Last night I thought about what I would say, and what came out of this is almost a credo of a New Age, things I believe, and they might be called 44 propositions in search of Psychology Tomorrow. They are in three sections, one disease, one healing, and one in terms of means. So I’ll read them. Forty-four propositions. 1. Our disease consists of our habit of treating symptoms. 2. Technology cannot heal our obsession with techniques. 3. Depression — psychological or economic — is the result of a destination crisis, not an energy crisis. 4. We have lost our ends, not our means. 5. Our critical shortage is one of goals, visions, imagination, a purpose for living. 6. It is dreams, not in action, that our missing purpose will be found. 7. The first thing to do is nothing. 8. In the beginning is the end. 9. Every process moves towards an undefinable goal. 10. All energy is already in form. 11. The ends create the means. 12. The question of value is prior to that of technique. 13. We are in transit toward an unknown destiny. 14. A human being is a citizen of two kingdoms, the here and now and the there and the then. 15. We are healed only by dreaming about a destination we cannot know. 16. We are preachers of a future province. 17. The human potential is unrealizable, thank God. 18. We are unfinished, therefore we hope. 19. We are animated by longing. 20. That which is not yet, is the motivating force. 21. Energy follows intention. 22. There is a dream dreaming us. 23. We do not belong to ourselves. 24. Anything that can be accomplished in a single lifetime, is too small a purpose to provide a meaning for living. 25. Any identity that can be found, deserves to be lost. 26. Who am I to presume to answer the question, who am I? 27. I am beyond anything I know myself to be. 28. Paranoia is the human condition. 29. Our unnatural calling is to learn to trust. 30. The human future depends upon the answer to one agonizing question, can we learn to be kind? 31. Fully human beings are not warriors. 32. We do not conquer life, we are not in control, we did not create the world. 33. There were fish before there were fisherman, indigo buntings before there were ornithologists, and believe it or not, a whole earth, before there was a Whole Earth Catalog. 34. Our first responsibility is to appreciate. 35. Philosophy and healing begin in wonder. 36. Silence precedes words. 37. Virile action begins in contemplation. 38. To God, we are all women. 39. Surrender to what is, before changing anything.

[buzzer went off]

42. We are in this world to wonder, and to be responsible for each other.

Sam Keen is the author of Apology For Wonder and To A Dancing God. His writing appears frequently in Psychology Today.

W.C. Ellerbroek

When we were little, we were taught that under certain circumstances, it is appropriate to be angry. And that under all circumstances, it is appropriate to be depressed.

. . . Anger is when your personal fantasy of how things ought to be isn’t matching your fantasy of how things are, but you feel that you might do something about it. Depression is a similar thing where you feel that your fantasy of how things ought to be and your fantasy of how things really are, aren’t matching and that there’s nothing that you can do about it.

. . . I believe that anger and depression are pathological emotions, that they are immediately responsible for the vast majority of human ills, including cancer, and I have accumulated a significant amount of very interesting material on this . . .

I have collected, from over this country, from various correspondents, 57 extremely well-documented cancer so-called miracles. A cancer miracle means that this person didn’t die, when they absolutely, positively were supposed to.

The cancer miracle, per se, doesn’t occur unless someone essentially is dying. That means they either have had all the treatment or no treatment, that the disease is far advanced, the medical profession has advised them not to waste their money on laetrile or quacks of various sorts, and that they should prepare themselves for a more or less graceful exit.

All 57 people had something in common except for eight. The 49 who match the larger pattern were angry, depressed people. They had been this way for a long while. Most doctors say that the depression comes after the cancer. I tell you no, it precedes it. Then comes additional anger and depression, about the disease. But always there is a negative affect state which precedes the onset of the tumor, of whatever type.

These 49 people were angry or depressed, usually both. But in many of them, the depression was paramount. They had all been through the routine as far as all kinds of treatment, including chemicals that made their hair fall out and vomit a lot and various other things. And a variety of surgeries of one sort or another.

One lady had practically nothing left as a matter of fact. She had a carcinoma of the cervix, she had her bladder removed, she had her rectum removed, she had a colostomy, she had an artificial bladder, she had a lot of extra things. And she still had lots of tumor and was sent home to die from a medical center. She . . . decided that she didn’t really want to die in the house. She thought she might be a little closer to God by going out by a little lake that was nearby where they lived. And so her husband wheeled a hospital bed down by the lake, and every night he’d wheel her back up to the house so she could sleep inside, and while she was out there, something happened and she decided to change her attitude.

This is exactly what the other 48 did also. At a particular moment in time, they decided that the anger and the depression was probably not the best way to go since they had such a little bit of time left. So they went from that to being loving, caring, no longer angry, no longer depressed, able to talk to the people that they loved, contrary to all expectations. This is only in 49 cases. The incidence of this is one out of 100,000 cancer cases which gives you an idea of how many really go. But these 49 people had the same pattern. They gave up, totally, their anger, and they gave up totally, their depression, by specifically a decision to do so. And at that point, the tumor started to shrink. Many of these had medical relatives who observed. None of these cases are from the backwoods, these are all validated from places beyond question.

The eight are more fascinating than the 49. The eight stayed angry and stayed depressed, and then, for whatever reason, each of the eight had either a stroke, a massive brain hemorrhage, or had a sudden hemorrhage into a mastoiditis in the brain. These eight people suddenly became comatose with a brain hemorrhage of some sort. They stayed in the coma, most of them in excess of three days, some were four or more, and then they gradually drifted back to consciousness, and they came back . . . with a violent personality change, exactly of the type that the other 49 arrived at by some type of emotional experience or cognitive process for some reason . . . It seems to me that it is possible that anger and depression, plus the carcinogens, is the way you explain the way that some people don’t go.

W.C. Ellerbroek is a staff psychiatrist at Metropolitan State Hospital in Los Angeles, Ca.

Robert Horvitz

Maybe it’s because I live on the east coast, where the situation is already more visibly desperate than here, but when I think about what the next five or ten years are likely to be like, I frankly get very scared. The myth of Beautiful Booming California masks the disillusionment and anxiety more evident in other parts of the country, and, for me, this gives this event a kind of “Night to Remember” quality — you know, the movie about the Titanic? . . .

I think this next decade will be a time of testing and redefining power relations, and not necessarily a pleasant one.

What scares me is that power displays are necessarily disruptive, and we are now so interdependent, so entrained, that what would remain a local problem in a looser system, in our system can cascade into larger disruptions under not-so-improbable conditions. And at the same time it’s ironic that precisely because of our interdependence, and the interdependence of our problems, it’s very hard to either fix blame or responsibility for solving problems. So, on the one hand, the system multiplies the power of its components through integration, but on the other hand, divides the responsibility of each component for the fate of the whole system. This is a very precarious situation — especially when going through a period of component power display.

This isn’t a new argument, but I started thinking about it again Friday night. Just before I fell asleep, I remembered something that a well-known California artist had said to me last January. We were talking about a show he was having in New York, and he said, “I’ve been thinking about this for a few years and I think it’s about time to start thinking about a ‘dictatorship of environment.’ ” This would be kind of an analogue to Marx’s concept of the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat.’ I guess the idea is that those who abuse the environment have to be smashed and held down for a time so they don’t re-emerge.

Now, I’ve never heard anyone else talk about a dictatorship of the environment. Most environmental people that I do come in contact with seem to have a kind of romantic, libertarian, passivist, anarchist or social-democratic philosophy. But this fellow reminded me that, at this point, there’s no logical link yet to any particular form of large-scale government in environmental thinking, and under crisis conditions, there’s actually a very strong totalitarian temptation — if you really believe we’re facing something like an ultimate state-of-emergency and species survival is at stake.

I don’t actually worry that much about environmentalism turning fascist — there being “Green Shirts” going around. What I do worry about is environmental slogans getting caught up in the kind of social conflicts I spoke of earlier and having their meanings turned inside out. Like the proletariat, the environment, as a symbol, lends itself to demagoguery. It’s an inclusive, apple-pie kind of concept, but it lacks a singular voice: just as there are conflicts of interest within the work-force, there are conflicts between species, and inclusive symbols make good camouflage for partisan ambitions. . . .

At this point, the environmental movement, I think, is largely still a cultural phenomenon. It’s a personal or family lifestyle; it’s a state of mind; it’s a cluster of fuzzily-linked preferences and beliefs anchored to a few successful examples and experiments. But I think we all must sense that if this continues without expanding onto new levels of organization, our concerns will be diluted and flattened into political cliches and ad copy for all-natural computer terminals and machine-made macrame.

Environmentalism may be nibbled to death by its friends and enemies alike. As far as I’m concerned, remaining a merely cultural phenomenon — a hip, white, intellectual, feel-good association — is as undesirable as going the authoritarian route. Fortunately, the middle paths still seem wide and plentiful. I hope we have the opportunity, and the will, to head down a good one.

Robert Horvitz is the art editor of CQ and a filmmaker.

Michael Phillips

The way each person handles their money can tell us nearly all there is to know about them; the way people exchange money with each other can tell us nearly all there is to know about their culture.

This is a new observation. Its potency in understanding our world is very great and it is a field of research open to all of us to investigate. Let’s do it together.

The following ten questions are my suggested starting point for this research:

- Why do many of us work much harder than necessary to have a comfortable rewarding life, often at jobs that we don’t enjoy?

- Why do most of us believe that money will provide security in our old age?

- How is it that some people keep very precise records of their money and others don’t? What are the effects of this?

- What is it precisely that each of us does with our money in terms of spending, saving and investing? What is it that we have acquired?

- Why do many of us say that we earn money for the good of our children yet we don’t believe that people with higher incomes have happier children?

- How is it possible in our culture to buy precisely $3.00 worth of gasoline but we can’t by $3.00 worth of food in a restaurant without difficult calculations? (For example, $3.00 minus a tip is $2.61, minus sales tax is $2.45 which is what we can spend on menu items to end up with a $3.00 total.)

- Why do most of the businesses we deal with make every effort to deceive us? For example, there are multiple vitamin pills selling in 6-ounce bottles for $2.98 that are heavily advertised as good for us. In the stores where we shop, anything we leave behind is likely to be taken by the employees as their own.

- Why don’t we see any connection between our unbridled right to acquire as many possessions as we want and the destruction of the natural environment around us?

- How can we have a society where all people are encouraged to acquire as many material possessions as they wish and yet be surprised at our very high crime rate?

- What is the connection between questions 1 through 5 and questions 6 to 9?

Michael Phillips works with the Glide Foundation in San Francisco, Ca. He is the author of The Seven Laws of Money.

Stewart Brand

The words that kept coming back to me, through the 50-some speakers we’ve had, was some kind of dialogue that goes on between grasp and reach. Ten years ago we reached for something, with the Whole Earth Catalog. Quite a lot of us reached for various things. Some to stop the war in Vietnam, some to save various species . . . and a lot of us spent ten years refining our activities so the grasp could catch our up with that reach. And that’s part of the strange transition that many of us have made from something like an outlaw to something like a citizen. I think we’re different citizens, and more valuable citizens for having been outlaws and I think we’re becoming more forgiving towards present and hopefully oncoming sets of outlaws; there will always be that dialogue.

For ourselves, if the grasp starts to catch up with the reach, and we start to do something rather well, well enough that it’s as if we could do it on our sleep, then probably we are doing it in our sleep. You should think about that grasp, that you’ve gotten out of the refinement of it, the goodness of it, that you are the citizen quality of behavior. I’m having to notice that sitting on boards, now. We have meetings. They are wonderful boards: Bread and Roses board, Magic Theater board.

. . . I start to look at the boredom or tedium that comes with doing what you’ve done well for a very long time, exclusively — I think this is the kind of thing that often overtakes public figures, and we as their public often force that on them, by insisting that Ralph Nader be strictly Ralph Nader. I’d love to see Ralph Nader trash a car. . . . All of us have this corner that we get into, by being public, by being good at what we’re doing. And I guess what I’m encouraging in myself and in anyone else who is interested or is thinking about these problems, is the diversity that we say is good for the ecology and the culture is also good for us.

Looking at various unusually useful peoples’ biographies, I notice that many of them have reflowerings. . . . I got spend an afternoon with Milton Friedman a couple months ago. Milton Friedman is one of the most interesting people to spent time with. I haven’t read his books; I think I will now. We were talking about the Nobel prize winners. He’s been one. . . . He said most of these guys get the prize and then they quit.

I think when you get your prize, you should think about opening up another line of work. . . . All of us should have in mind to keep various kinds of potential hobbies that might take off and become a line of work, working for other kinds of people in other kinds of jobs, so that our own diversity can increase and match the diversity we are trying to bring about everywhere.

Stewart Brand is the editor of the CQ. He rode with Ken Kesey as one of the Merry Pranksters in the Sixties.