Horses

Pablo Neruda From the window I saw the horses. I was in Berlin, in winter. The light was without light, the sky without sky. The air white like wet bread. And from my window a vacant arena, bitten by the teeth of winter. Suddenly, led by a man, ten horses stepped out into the mist. Hardly had they surged forth, like flame, than to my eyes they filled the whole world, empty till then. Perfect, ablaze, they were like ten gods with wide pure hoofs, with manes like a dream of salt. Their rumps were worlds and oranges. Their color was honey, amber, fire. Their necks were towers cut from the stone of pride, and behind their transparent eyes energy raged, like a prisoner. And there, in the silence, in the middle of the day, of the dark, slovenly winter, the intense horses were blood and rhythm, the animating treasure of life. I looked, I looked and was reborn: without knowing it, there was the fountain, the dance of gold, the sky, the fire that revived in beauty. I have forgotten that dark Berlin winter. I will not forget the light of the horses.

For a Five-Year-Old

Fleur Adcock A snail is climbing up the window-sill into your room, after a night of rain. You call me in to see, and I explain that it would be unkind to leave it there: it might crawl to the floor; we must take care that no one squashes it. You understand, and carry it outside, with careful hand, to eat a daffodil. I see, then, that a kind of faith prevails: your gentleness is molded still by words from me, who has trapped mice and shot wild birds, from me, who drowned your kittens, who betrayed your closest relatives, and who purveyed the harshest kind of truth to many another. But that is how things are: I am your mother, and we are kind to snails.

Bats

Randall Jarrell A bat is born Naked and blind and pale. His mother makes a pocket of her tail And catches him. He clings to her long fur By his thumbs and toes and teeth. And then the mother dances through the night Doubling and looping, soaring, somersaulting — Her baby hangs on underneath. All night, in happiness, she hunts and flies. Her high sharp cries Like shining needlepoints of sound Go out into the night and, echoing back, Tell her what they have touched. She hears how far it is, how big it is, Which way it’s going: She lives by hearing. The mother eats the moths and gnats she catches In full flight; in full flight The mother drinks the water of the pond She skims across. Her baby hangs on tight. Her baby drinks the milk she makes him In moonlight or starlight, in mid-air. Their single shadow, printed on the moon Or fluttering across the stars, Whirls on all night; at daybreak The tired mother flaps home to her rafter. The others all are there. They hang themselves up by their toes, They wrap themselves in their brown wings. Bunched upside-down, they sleep in air. Their sharp ears, their sharp teeth, their quick sharp faces Are dull and slow and mild. All the bright day, as the mother sleeps, She folds her wings about her sleeping child.

The Dead Seal Near McClure’s Beach

Robert Bly

1

Walking north toward the point, I come on a dead seal. From a few feet away, he looks like a brown log. He is on his back, dead only a few hours. I stand and look at him. There’s a quiver in the dead flesh. My God he’s still alive. A shock goes through me, as if a wall of my room had fallen away.

The head is arched back, the small eyes closed, the whiskers sometimes rise and fall. He is dying. This is the oil. Here on its back is the oil that heats our houses so efficiently. Wind blows fine sand back toward the ocean. The flipper near me lies folded over the stomach, looking like an unfinished arm, lightly glazed with sand at the edges. The other flipper lies half underneath. The seal’s skin looks like an old overcoat, scratched here and there, by sharp mussel-shells maybe . . .

So I reach out and touch him. Suddenly he rears up, turns over, gives three cries, Awaaark! Awaaark! Awaaark! — like the cries from Christmas toys. He lunges toward me. I am terrified and leap back, although I know there can be no teeth in that jaw. He starts flopping toward the sea. But he falls over, on his face. He does not want to go back to the sea. He looks up at the sky, and he looks like an old lady who has lost her hair.

He puts his chin back down on the sand, rearranges his flippers, and waits for me to go. I go.

2

Today I go back to say goodbye. He’s dead now. But he’s not — he’s a quarter mile farther up the shore. Today he is thinner, squatting on his stomach, head out. The ribs show more — each vertebra on the back underneath the coat is now visible, shiny. He breathes in and out.

He raises himself up, and tucks his flippers under, as if to keep them warm. A wave comes in, touches his nose. He turns and looks at me — the eyes slanted, the crown of his head looks like a boy’s leather jacket bending over his bicycle bars. He is taking a long time to die. The whiskers white as porcupine quills, the forehead slopes . . . goodbye brother, die in the sound of waves, forgive us if we have killed you, long live your race, your inner-tube race, so uncomfortable on land, so comfortable in the ocean. Be comfortable in death then, when the sand will be out of your nostrils, and you can swim in long loops through the pure death, ducking under as assassinations break above you. You don’t want to be touched by me. I climb the cliff and go home the other way.

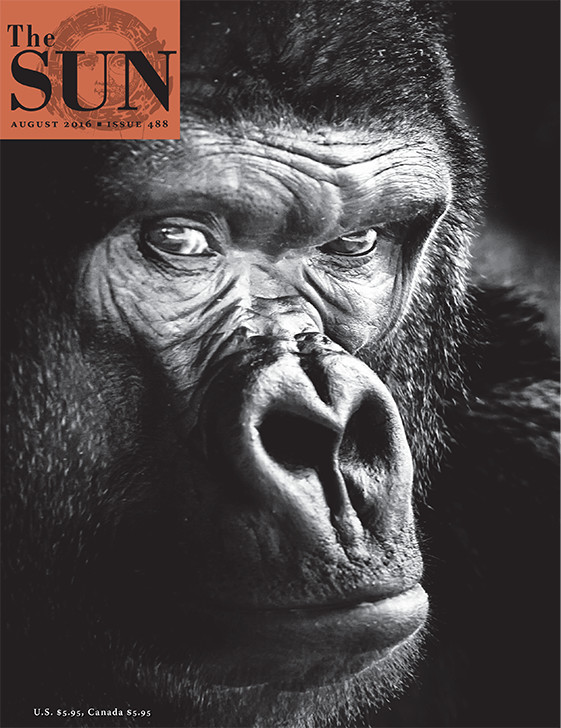

The Panther

Rainer Maria Rilke In the Jardin des Plantes, Paris His vision, from the constantly passing bars, has grown so weary that it cannot hold anything else. It seems to him there are a thousand bars; and behind the bars, no world. As he paces in cramped circles, over and over, the movement of his powerful soft strides is like a ritual dance around a center in which a mighty will stands paralyzed. Only at times, the curtain of the pupils lifts, quietly. An image enters in, rushes down through the tense, arrested muscles, plunges into the heart and is gone.

Magic Words

Nalungiaq In the very earliest time, when both people and animals lived on earth, a person could become an animal if he wanted to and an animal could become a human being. Sometimes they were people and sometimes animals and there was no difference. All spoke the same language. That was the time when words were like magic. The human mind had mysterious powers. A word spoken by chance might have strange consequences. It would suddenly come alive and what people wanted to happen could happen — all you had to do was say it. Nobody can explain this: That’s the way it was.

“Horses” is from Full Woman, Fleshly Apple, Hot Moon: Selected Poems of Pablo Neruda, by Pablo Neruda. Translated by Stephen Mitchell. Copyright © 1997 by Stephen Mitchell. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

“For a Five-Year-Old” is from Poems 1960–2000, by Fleur Adcock. Copyright © 2000 by Fleur Adcock. Reprinted by permission of Bloodaxe Books.

“Bats” is from The Complete Poems by Randall Jarrell. Copyright © 1969, renewed 1997 by Mary von S. Jarrell. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

“The Dead Seal Near McClure’s Beach” is from The Morning Glory, by Robert Bly. Copyright © 1972 by Robert Bly. Reprinted by permission of Georges Borchardt, Inc., on behalf of the author.

“The Panther” is from Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, by Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Stephen Mitchell. Translation copyright © 1982 by Stephen Mitchell. Used by permission of Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

“Magic Words” by Nalungiaq is from Songs and Stories of the Netsilik Eskimos, edited by Edward Field. Published by Education Development Center (1968) and reprinted by permission of Edward Field.