The cannabis plant had been used by humans as medicine and enjoyed for its psychoactive properties for thousands of years, but in 1937 it came under strict federal regulation in the United States. Harry J. Anslinger, the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics — who made some notoriously racist comments — waged war on cannabis, also called “reefer” or “marihuana,” Mexican slang for “the weed that intoxicates.” In 1971 President Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs,” and every federal administration since has continued the campaign. Despite this, almost all Americans now live in states where cannabis is legal to use in some form as medicine, and in eighteen states it’s legal for adults to use for recreation. It is regulated and taxed by state and local governments, which often spend that revenue on badly needed social services. Medical cannabis is used to treat multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, nausea caused by cancer treatments, and other ailments.

Journalists Nushin Rashidian and Alyson Martin have written about cannabis and drug policy for more than ten years in The Atlantic, Esquire, The Nation, and other publications. “It seems that nothing can kill the cannabis plant,” they write, “not seventy-five years of prohibition, nor decades of reefer madness, nor forty years of the drug war.” Yet the federal government continues to treat cannabis as having no medicinal value and considers it as dangerous as heroin. Millions have been arrested for marijuana possession, a disproportionate number of them Black or brown. Martin and Rashidian founded the news organization Cannabis Wire to report on marijuana regulation and law, the economics and science of its cultivation and use, and the implications its legal status has for criminal justice and individual liberties (cannabiswire.com). Rashidian told me that from the start they “were really passionate about educating journalists to ask the right questions, to give them the tools they needed to cover a subject that was very new for many of them.” She and Martin are the coauthors of A New Leaf: The End of Cannabis Prohibition, which examines the history of cannabis use and the road to today’s imperfect, ever-shifting legal and scientific status quo.

Martin attended the College of Saint Rose in her hometown of Albany, New York, while Rashidian studied at the University of California’s Irvine campus; both obtained advanced degrees from New York City’s Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, where they met and are now adjunct faculty. For many years they traveled the country, from Seattle to Washington, D.C., covering news stories about cannabis. (Martin says she’s driven across the U.S. six times in her red VW Beetle.) Right now the COVID-19 pandemic has confined them to their home base in New York City. We talked by video chat.

Nushin Rashidian (left) and Alyson Martin

Leviton: How much illegal drug use is there in the United States?

Nushin Rashidian: In the U.S. around 35 million people over the age of twelve use a drug illegally during any given month. If you remove those who only consumed cannabis, that number drops below 10 million. Yet half of all drug arrests are for cannabis. Given that extent of use, with relatively little harm, it makes sense that so many Americans support cannabis legalization. The prevailing view is that the known harms of prohibition outweigh the possible harms of legalization, and that arresting and incarcerating people for drug use doesn’t make a lot of sense.

Leviton: The federal government classifies drugs on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being the most dangerous and subject to the toughest restrictions. Anabolic steroids and Tylenol with codeine are Schedule 3. Methamphetamine and Vicodin are both Schedule 2. Marijuana, along with heroin and LSD, is Schedule 1. What does that mean for advocates of legalization?

Nushin Rashidian: It’s not really logical that cannabis ended up on Schedule 1, which is reserved for drugs with no accepted medical use and the highest potential for abuse. Cannabis actually does have valid medical applications.

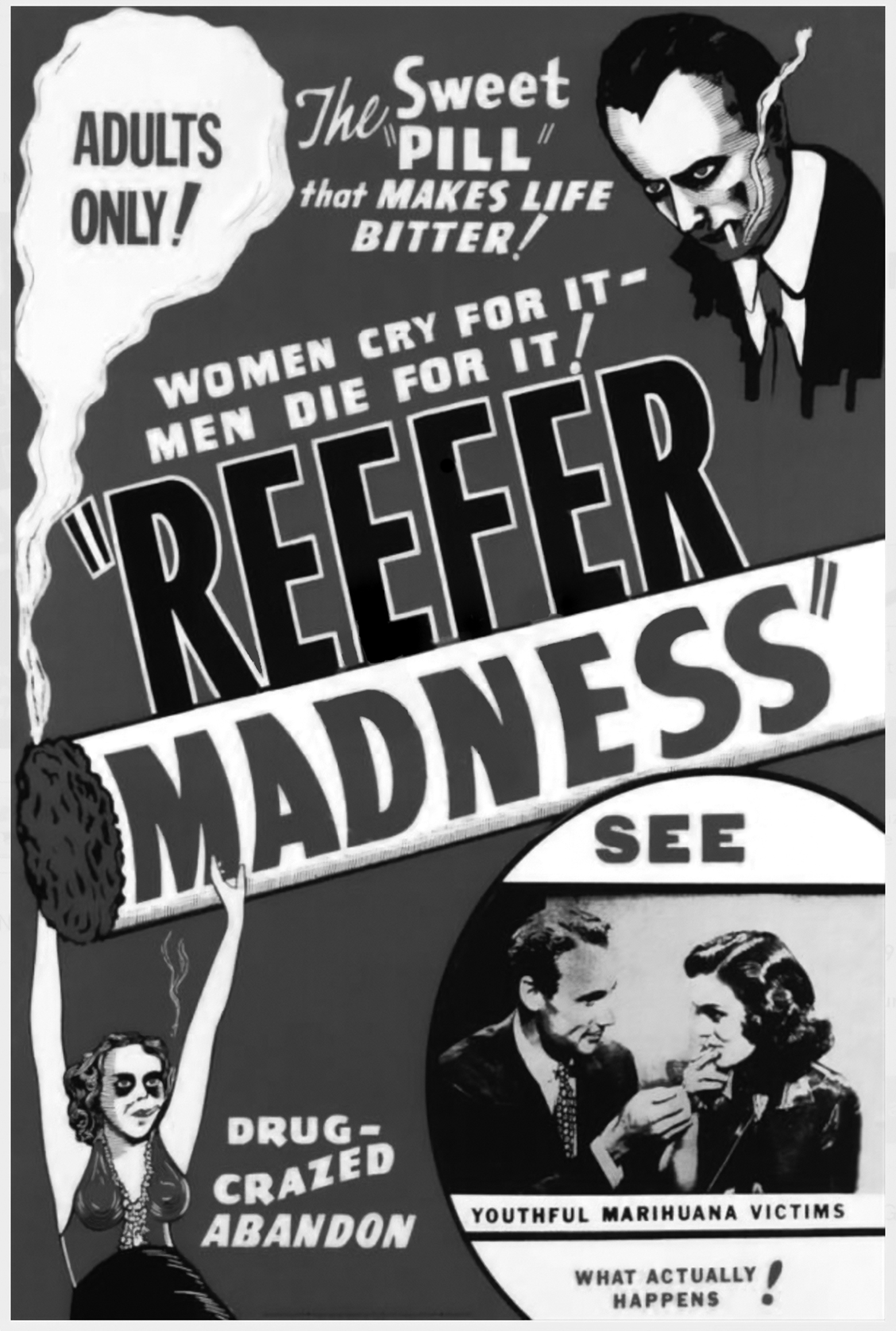

There’s long been a racially tinged hysteria about “marijuana.” We might laugh now at the 1930s film Reefer Madness, but it represented the pervasive belief that cannabis was being pushed on “vulnerable” white people by out-of-control Black and Mexican people. The reason Alyson and I prefer to use the word cannabis instead of marijuana is because it’s more scientifically accurate. But there is another reason: the drafters of the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act — which didn’t prohibit cannabis but did try to tax it out of existence — purposely used the word marihuana for the plant to make something familiar, cannabis, sound unfamiliar and foreign.

Schedule 1 classification also creates barriers to research. Today there is only one federally approved producer of research-grade cannabis — at the University of Mississippi at Oxford. In 2018 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Epidiolex, a cannabidiol (CBD) oil, for use by children with epilepsy. CBD interacts with the body’s endocannabinoid system, but it doesn’t get you high.

Leviton: At this point, how many states have legalized cannabis for either medical or recreational use?

Alyson Martin: It’s a patchwork. Eighteen states and Washington, D.C., have legalized cannabis for adult use. Almost all states have legalized some form of medical cannabis, but some are “CBD only,” which means that the entire cannabis plant has not been legalized for medical use: THC, the main psychoactive compound in cannabis, is excluded. It produces the high. Just to confuse matters further, if a cannabis plant has a THC concentration of 0.3 percent or less, it’s classified as hemp, and totally legal. The federal 2018 Farm Bill removed hemp from the Controlled Substances Act, but hemp cultivation is still highly regulated.

For years in Georgia, for example, parents of children with epilepsy could possess CBD oil to treat their kids, but there was no legal method for procuring it. But since 2019 Georgia’s governor has signed legislation to allow for in-state production and sale by several companies.

Nushin Rashidian: In Texas, which has a “CBD only” law, there are three companies in the entire state that can legally sell it, so it’s not a full medical-cannabis program.

A lot of the classification — this is cannabis, this is hemp; this is medical, this isn’t — is arbitrary. The cannabis you buy in a medical dispensary is the same as what you’re buying in a “recreational” shop. CBD derived from hemp is the same as CBD derived from “marijuana.” The Farm Bill didn’t legalize “hemp”; it legalized low-THC cannabis. But I doubt Senator Mitch McConnell [Republican from Kentucky] would have been a big supporter of the bill if it had been framed as a cannabis-legalization bill.

It’s not really logical that cannabis ended up on Schedule 1, which is reserved for drugs with no accepted medical use and the highest potential for abuse. Cannabis actually does have valid medical applications.

Leviton: Legal cannabis is already an $8 billion annual business, but that pales in comparison to domestic sales of alcohol, which topped $250 billion last year. Could it be that the predictable effects of alcoholic drinks — you consistently get the same results from the same dose and brand — is a crucial factor in its market success? By contrast, marijuana fails to provide a reliable, identical high every time, so many people are wary of it.

Alyson Martin: It’s important to note that the effects of cannabis vary widely by individual. Raphael Mechoulam, the Israeli scientist and researcher who discovered THC, refers to the cannabis plant as “cannabinoid soup.”

Smoking cannabis or using a vaporizer could affect people differently than eating an edible, like a lozenge or a cookie, with the same THC level. Then there are other factors: How hydrated are you? Have you eaten a meal lately? What’s your weight? Are you a first-time cannabis consumer? An intermittent consumer? Someone who consumes on a regular basis?

Leviton: Can cannabis ever be addictive?

Nushin Rashidian: Can you become dependent on cannabis? Sure, just as you can on gambling or shopping. The cannabis industry should encourage conversations about possible dangers. It’s not anti-cannabis to say, “Don’t drive stoned.” We need information about not just teenage use but adult use, too. What are the short- and long-term effects?

Alyson Martin: Research is definitely expanding on adolescent use and use during pregnancy. Former U.S. surgeon general Jerome Adams issued an advisory in 2019 about those two groups. Recent studies show that teen cannabis vaping is on the rise, and that use by pregnant women is prevalent and problematic, which are areas of focus for law- and policymakers, who might, for example, craft public-education campaigns targeted at these populations.

Can you become dependent on cannabis? Sure, just as you can on gambling or shopping. The cannabis industry should encourage conversations about possible dangers. It’s not anti-cannabis to say, “Don’t drive stoned.”

Leviton: When I was using medical marijuana in 2016 during cancer treatments, I purchased some chocolate-coated blueberries that contained five milligrams of THC each. I was fine when I ate one. On another occasion I had two, and I was still OK. But when I had three, I had the most unpleasant reaction to cannabis in my life. For the first time I believed there was such a thing as a cannabis overdose.

Alyson Martin: It can be unpleasant. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identifies “too much” THC as causing confusion, anxiety, paranoia, a faster heart rate, increased blood pressure, nausea, and hallucinations. The kind of experience you had with edibles is certainly real. Back in 2014 Maureen Dowd of The New York Times went to Colorado to cover cannabis legalization and wrote about ingesting a cannabis-infused candy bar and having such a bad experience that she thought she had died. Regular cannabis consumers ridiculed her mercilessly, but she started an important conversation. Colorado had not focused sufficiently on dosage in products. To save on manufacturing and packaging, dispensaries used to sell one cookie and tell consumers to cut it into many pieces. After that column appeared, Colorado began to limit how much THC could be in a single serving and focused on public education around dosing.

We also need to know more about terpenes, which are what you smell when you consume cannabis. It’s part of the experience, like the bouquet of wine. Terpenes may play a role in the effects of cannabis. Again, though, we need more research.

But, no matter what, consumers are going to have to figure out how different factors combine to create a certain experience. Neither public-health officials nor cannabis dispensaries have a one-size-fits-all answer. A lot of people will say, “You know, this isn’t your grandpa’s weed,” and the truth is we are seeing much stronger products in the legal market. Anecdotally there’s indication that the presence of CBD could mitigate some of the effects of THC, but it’s not conclusive.

Leviton: It seems that the majority of Americans would like cannabis to be legalized, but their elected representatives are overwhelmingly not acting on that desire.

Alyson Martin: I think that’s accurate. If New Yorkers could have voted on full legalization, they probably would have approved it five or ten years ago. [New York] Governor [Andrew] Cuomo signed the legalization bill passed by the legislature in March, but legal buying or selling could still be two years off. Alabama’s governor signed a medical-cannabis-legalization bill this year. There may be some conservative areas of the U.S. where cannabis sales will never be legal for any reason — akin to the “dry counties” that prohibit alcohol sales entirely. Idaho might be the very last state to act.

If it were up to the voters, we’d already have national legalization. At this point Pew surveys show 60 percent of Americans support legalizing cannabis for both medical and adult recreational use, and 31 percent support medical only. Just 8 percent of Americans polled this year thought cannabis should be illegal in all circumstances.

Nushin Rashidian: I think it would be useful for Pew and Gallup, the major polling organizations, to start asking more-detailed questions about cannabis. You can legalize cannabis in a way that enriches either private companies or the state. How you tax cannabis and how you license sales has public-health and economic implications and can ensure that people who have been disproportionately harmed by the war on drugs get to participate in this new economy.

Leviton: What are the arguments against legalizing cannabis at this point?

Alyson Martin: The most common argument is essentially a moral one: that allowing or encouraging intoxication is bad and leads to ruined lives.

Another argument is that big corporations are trying to dupe us into legalizing cannabis so they can make a lot of money from a dangerous product. Just like Big Tobacco or Big Pharma, “Big Marijuana” wants to come into your state and sell cannabis cigarettes to your teens.

A lot of religious people are opposed even to medical use, and police are largely opposed to legalization, at least publicly. Opposition also comes from what I’d call the “recovery industry” — mostly rehab facilities. Many of those have religious roots and use the morality argument.

Nushin Rashidian: When it comes to legalization of cannabis classified as “hemp,” I’m shocked at how quickly people who were opposed to it for decades have reversed their positions. Why now? It’s kind of baffling. For years activists couldn’t get politicians to understand that hemp is a benign product, not an intoxicant. But legislators refused to legalize it because they believed people would smoke it to try to get high. Since 2018 it’s been a nonissue even among Republicans. They’re no longer against cannabis; they’re against the type of cannabis that gets you high — and the “permissive culture” they associate with that.

Leviton: The public has shown a willingness to allow state lotteries and legalized gambling as a way of raising money for infrastructure, schools, and so forth. Could cannabis legalization create another “sin tax” for the public good?

Alyson Martin: “Pot for potholes” is a frequent talking point in favor of legalization, but voters are becoming less interested in that argument. They want schools and health care funded all the time, not just when the state gets a lot of cannabis-tax revenue. And should the argument for legalization focus solely on raising revenue?

Nushin Rashidian: I think the racial-justice argument is stronger. When cannabis is legalized, fewer people of color go to jail, with all the destruction that causes, and cannabis-tax revenues can be used to redress systemic inequality. Increasingly states are earmarking that tax revenue for social-equity purposes: low-interest or no-interest loans, grants, or to fund efforts to expunge people’s criminal records of arrests for cannabis possession. Also, those disproportionately affected by the enforcement of anti-cannabis laws are now sometimes prioritized to receive cannabis business licenses.

Overall, states that have legalized cannabis are trying to create pathways to success for those who don’t have the same resources as big businesses, which are often run by wealthy white people. Where the criminalization of cannabis has hurt certain communities, some state legislators want to use legalization to help them. It’s a chance to repair the damage done by unjust enforcement of antidrug laws.

Alyson Martin: In 2013 the American Civil Liberties Union [ACLU] issued a report called The War on Marijuana in Black and White. It found cannabis use was roughly even in Black and white communities, but Blacks were three and a half times more likely to be arrested for possession. That statistic remained unchanged in an ACLU study from 2020, even with full or partial legalization in many states.

Any cannabis arrest has a trickle-down effect. It’s not just the original jail time or fine that wrecks lives; it’s the way our laws pile on additional consequences. You can lose your housing subsidy, custody of your child, or access to student loans and other benefits.

Leviton: What’s the current position of the banking and credit systems with regard to legal cannabis? Is there a kind of gray market operating?

Nushin Rashidian: It’s a mess is what it is. A lot of banks won’t deal with cannabis businesses out of fears of federal backlash, even though the government has shown no real interest in busting banks. It’s not that the cannabis industry has zero access to banking. There are still hundreds of banks and credit unions willing to do business with them. In some cases cannabis businesses have hidden banking and credit arrangements.

We had our own run-in with this when we founded Cannabis Wire as a news organization. As a subscription service we needed to establish a paywall, and we couldn’t use one of the premier services because we had cannabis in our name.

Leviton: In 2009, during the Obama administration, Attorney General Eric Holder announced an end to the Bush era’s frequent raids on medical-marijuana distributors, with the Department of Justice (DOJ) restricted to raiding drug traffickers who masqueraded as legal dispensaries. What’s the current situation?

Nushin Rashidian: There were actually two major DOJ memos issued under Obama. The 2009 memorandum, suggesting the federal government would have a hands-off policy when it came to medical cannabis, created something of a free-for-all. Then, in 2013, a second memo laid out some enforcement priorities: no cannabis transported across state lines; no cannabis sold to minors; no cannabis activity on public lands. If you obey state laws, it said, you’re OK, but if you do any of these things, we’re coming after you.

When Donald Trump got into office, Attorney General Jeff Sessions rescinded the Obama memos but didn’t issue anything in their place, which left considerable confusion. He took away everyone’s security blanket but did not launch a crackdown.

Alyson Martin: But all state laws regarding legalization are in conflict with federal law. This is why there’s so much lobbying for the Secure and Fair Enforcement (SAFE) Banking Act, which passed the House of Representatives again this year but still hasn’t passed in the Senate. It would open up access to financial services for legitimate cannabis-related businesses, open up lending, and protect banks.

Poster for the 1972 rerelease of an anti-cannabis propaganda film from the 1930s.

Leviton: It’s probably a fool’s errand to think you can write a law that takes into account every contingency.

Alyson Martin: Yes, we joke that regulating the cannabis industry is like playing whack-a-mole: knock one loophole down, and another pops up. Unless the legislation specifically says you cannot sell cannabis while playing softball in a recreation league, some people will sell cannabis while playing softball in a recreation league. People will find loopholes or invent new products that legislators can’t anticipate.

In Washington, D.C., the law doesn’t allow you to sell cannabis, but you are allowed to give it away. So someone could order a pizza for a hundred dollars and get a quarter ounce of cannabis “for free,” or purchase a T-shirt for forty dollars and have a “free sample” of cannabis tossed in the bag. In Nevada a decade ago it was legal to make a “donation” to someone who just happened to grow cannabis, and the grower could share it with you. Pretty soon people were “donating” for a five-minute session with a “cannabis consultant” and walking out with cannabis.

Nushin Rashidian: As long as the laws are generally reasonable, people tend to follow them. But anytime the laws are viewed as an imposition, you’ll see workarounds. Where the law doesn’t license cannabis businesses or imposes draconian requirements, that leads people to explore these gray areas.

Leviton: When the first medical-marijuana initiatives began, there was opposition from illegal growers, who feared government intervention, taxation, OSHA requirements, and so forth. In the pot-growing area of Northern California where I live, many progressives were urging “no” votes.

Nushin Rashidian: That kind of opposition was pretty localized to what’s called the Emerald Triangle: Humboldt, Mendocino, and Trinity Counties in California. A strong gray market has been thriving there for many years and basically supplying cannabis to the entire country. For those growers, legalization meant a steep licensing fee, zoning permits, quality control, and limits on the size and location of cannabis farms — all levied on a business that had been operating for decades without such requirements.

Alyson Martin: I will add one thought about the Emerald Triangle: The California Department of Food and Agriculture is laying the groundwork for a statewide certification program that will establish standards for region-specific cannabis labeling. I expect Humboldt cannabis, which is already known around the world, will become even more identified with high quality and will be promoted as the “Champagne of cannabis,” analogous to the French grape-growing region that is the only place authorized to call its wine “champagne.”

Leviton: Are we on track for federal legalization at some point?

Alyson Martin: Before the pandemic I would have said we might get there this year. Now I’m thinking more like 2024. President Biden has said he doesn’t think cannabis consumers should go to jail, but he has opposed national legalization, punting to the states.

Nushin Rashidian: The situation we have now, with so many state laws in conflict with federal law, is unprecedented. It’s difficult to report on cannabis because we have to attach so many footnotes and caveats: cannabis is legal for adult use in both D.C. and New Jersey, but in the former you can grow it for personal use but not sell it in shops, while in the latter you can sell it in shops but not grow it for personal use.

Pew surveys show 60 percent of Americans support legalizing cannabis for both medical and adult recreational use, and 31 percent support medical only. Just 8 percent of Americans polled this year thought cannabis should be illegal in all circumstances.

Leviton: Does the U.S. Food and Drug Administration play a role with respect to cannabis?

Alyson Martin: Absolutely. We already talked about the FDA approving Epidiolex for the treatment of two rare forms of epilepsy. One approved cannabis-derived product opens the door for more. On its website the FDA says it sees the “potential opportunities” of cannabis-derived compounds, but also that some companies are already marketing products containing cannabis in ways that violate the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and might compromise the health and safety of consumers.

Nushin Rashidian: You cannot take the active ingredient of an approved pharmaceutical and insert it into food. So now that there is an approved CBD drug, technically all these CBD beverages and cookies contain a pharmacologically active compound, and the FDA now has the unenviable job of dealing with the proliferation of these products. It might decide to allow CBD below a certain level or to treat salves and lotions differently than items we ingest.

Leviton: I just saw a New York Times article about Martha Stewart’s new CBD-edibles business.

Nushin Rashidian: The FDA shot itself in the foot by taking so long to release rules for CBD, which still hasn’t happened. Meanwhile this unregulated market thrives, and consumers are getting used to seeing CBD everywhere: in salons, in vitamin shops, even in Bed Bath & Beyond. They have a CBD-infused pillowcase!

But if the FDA rushes out the guidelines, it runs a real risk of getting it wrong. I think the Farm Bill complicated things by making all cannabinoids except THC legal. So now anything the FDA does for CBD might have to apply to dozens of other cannabinoids that are in the flower, even in negligible quantities.

Any cannabis arrest has a trickle-down effect. It’s not just the original jail time or fine that wrecks lives; it’s the way our laws pile on additional consequences. You can lose your housing subsidy, custody of your child, or access to student loans and other benefits.

Leviton: What other uses of cannabis are being studied?

Alyson Martin: Ziva Cooper, the research director of UCLA’s Cannabis Research Initiative, has been studying the impact of cannabis on opioids, trying to determine whether people who use cannabis can get sufficient pain relief from lower doses of opioids. Humans have an endocannabinoid system on which compounds in cannabis act. This system is implicated in a number of things, from mood to appetite. Our bodies produce endocannabinoids, which is why we have receptors for them, and those receptors also respond to cannabis. So researchers are studying the therapeutic potential of cannabis for conditions like pain and PTSD, among many others.

Leviton: Won’t big pharmaceutical companies take over the cannabis industry?

Alyson Martin: There are actually three giant industries looking at the cannabis business: alcohol, tobacco, and pharmaceutical. There’s still the question: Is cannabis medicine or a nightcap? Is it a drug you get from CVS or a plant you grow in your garden? Big Ag could add cannabis to the long list of products it controls, too. You can go online and read conspiracy theories about [corporate agriculture giant] Monsanto for days.

Leviton: What do you think will be the future of cannabis?

Nushin Rashidian: I think we’ll see research that will allow people to make informed decisions and an end to the drug war and the disparities in arrest and incarceration rates that have come with it. It seems inevitable that cannabis is going to be federally legalized at some point. Republicans like the probusiness aspect and support the states’-rights issue, which is why one cannabis bill in Congress was called the Strengthening the Tenth Amendment through Entrusting States (STATES) Act. But Republicans would like to leave LGBTQ+ rights and abortion rights to the states as well, so progressive cannabis advocates really have to think about the possible side effects of using the states’-rights argument to legalize cannabis.

There’s also the Marijuana Opportunity, Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act, which, as you can see from its name, puts social justice at the center, using taxation to address the harms of racism in policing and so forth. It was passed by the House of Representatives in December 2020 but did not advance in the Senate. It was just reintroduced this year. Some people want state-run cannabis stores, with private industry completely excluded. Others want the whole industry to run like your local farmers market.

Alyson Martin: Cannabis is legal in Canada for both adult and medicinal use. Mexico could legalize cannabis by the end of this year. The United States is going to be squeezed on both sides, with Americans vacationing in Cabo San Lucas and Montreal, using legal cannabis, and perhaps wondering why their own country isn’t moving forward with similar policies.

Nushin Rashidian: New Zealand had a legalization referendum that was narrowly rejected in September. Australia is starting, region by region, to study this. Globally it’s happening. It’s going to happen slowly, of course, like anything else.

When cannabis is legalized, there’s still a question about whether it is going to essentially map against other commodities or whether it will set a new normal in terms of the social responsibility of corporations: Is this going to be more mom-and-pop? Is it going to be more multinational? Are we going to have the haves and the have-nots? So far I’m not super encouraged that it isn’t just going to fall into ye olde patterns of inequity like any trade: the flower trade, the coffee trade, the sugar trade. What is a global market for cannabis going to look like, and will it repeat some of the unsavory and problematic patterns of the past? I think it still has a chance to not repeat them, but I’m concerned that it could.