I spent a week in South Carolina, in a coastal community called Garden City, near Myrtle Beach, where they’re “reclaiming” the beach. Sand is pumped in, water runs out, while vacationers in their dream houses contemplate the vastness and timelessness and unimaginable fury of the sea they’re cheating.

At least every twenty-five years a monster hurricane pounds the shore; in 1954, hurricane Hazel swept up many of the cottages along here. The local guidebook mentions the devastation in passing, noting that “in their place, new and better structures sprang up.” To the architects of progress better goes with new the way dollars go with cents. The speculators clean-up; the old-timers shake their heads with a rueful smile.

Back in Chapel Hill, I get a call from my friend Karl Grossman. He’s just finished a book about nuclear energy; we talk about the dirty dreams of the oil companies, the Trilateral Commission, the media. “The press is a death machine,” he says. “You knew that 10 years ago, when you got out.” I ask about old friends. One landed a top job on a metropolitan daily. “He hates it,” Karl says. “He’s the education editor, and all they want is stories about rapes in the schools.”

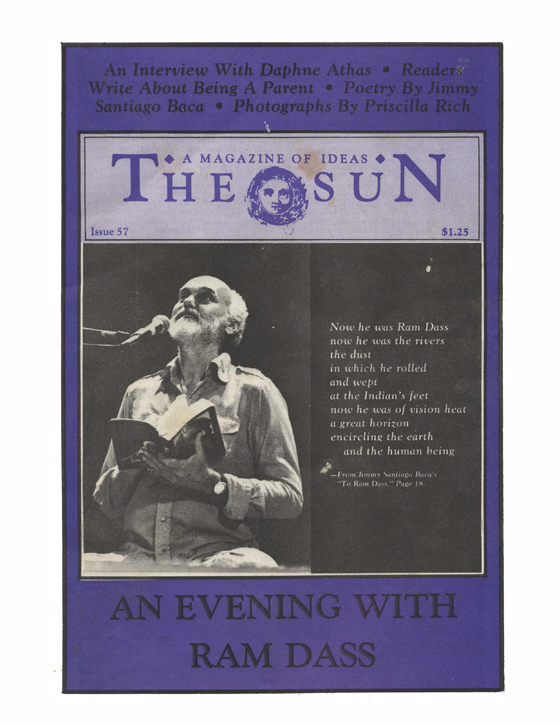

“The paradox,” Ram Dass says, “is that it’s all perfect and it all stinks. A conscious being lives simultaneously with both of these.” I try. It’s the goal-less goal. Between the sheets and the skin, the alarm and the rising, the first word and the last, I make a life — lost neither in New Age pastels nor blood-red skies, neither in innocence nor conspiracy.

The future isn’t cheated; it’s seamless with the present and the past — an ocean of time no more made up of separate events than the ocean I gazed at all week was made up of separate drops. Yet we forget that, sell out the future or yoke it to fear, or turn it into a Hollywood sunset.

I have my romances, too — better than Hollywood, more deadly — and, sure as the movie ends, I see them dissolve in a pool in the mind, the waters of my own forgetfulness lapping against me.

— Sy