Late last year Apple’s stock price rose enough to value the company at $3 trillion, an amount higher than the GDP of all but seven countries in the world. The fact that I am typing this—for a nonprofit, ad-free, independent publication—on a product made by Apple, or that I use an iPhone to conduct much of my life, is not lost on me. But finding an alternative that offers the same ease of use and efficiency seems far from simple.

The author and programmer Wendy Liu faced a similar quandary while working as a founder and chief technology officer of an advertising-technology start-up in the mid-2010s: her career path was promising, but she worried about the tech industry’s influence on the world. As an adolescent she’d been fascinated by the potential of the internet and open-source software, and she’d gone on to hone her programming skills as a mathematics and computer-science major at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. After her junior year she took a summer internship at Google’s San Francisco office. She was initially dazzled but quickly became disenchanted by the company’s ownership of her work and the economic disparities she saw both in and out of the office. After graduation a six-figure salary at Google was on the table, but she wanted to be her own boss, to “believe that my ingrained work ethic flowed from a higher truth,” as she writes in her 2020 memoir, Abolish Silicon Valley: How to Liberate Technology from Capitalism.

Three years of the financial and moral implications of running a start-up made Liu want to do something more valuable for society. In 2017 she entered a master’s program at the London School of Economics and Political Science, where she began reading about the labor movement and capital’s treatment of workers. Her worldview shifted, and the promise of sky-high profits that defines much of start-up culture now rang hollow. She saw how rapid growth enriches those at the top while outsourcing work to parts of the world that have less equitable pay. Even highly skilled workers in Silicon Valley are not guaranteed a sustainable career. (More than 260,000 tech workers were laid off in 2023.) And the success of companies in the Bay Area has had an inverse effect on the living conditions of many of its residents.

I met Liu last fall for this interview in downtown San Francisco. Exiting the train from Oakland, I quickly got lost, and the Google Maps application on my phone wouldn’t help me find the restaurant we had agreed upon. (That Google’s office was nearby seemed like a cruel joke.) As I wandered the vicinity, I noticed the juxtaposition of human misery and ostentatious displays of wealth that has been written about in the media for the last few years. People were living in tents on sidewalks as others walked by immersed in their phones. A Tesla passed a limping man holding a half-empty jug of milk and rolling a suitcase across a street. Security guards at a boutique clothing store ran another man out of a median, where he was trying to defecate.

Once I found the restaurant, Liu and I had a sobering conversation. She no longer works in technology, though she still codes for personal enjoyment. She is waiting tables at a restaurant in San Francisco and working on a novel, her first, about Silicon Valley. We talked about the veneer of altruism the tech industry uses to hide its rapaciousness, why she no longer believes digital progress is driven by good intentions, and the rampant economic disparity in the region.

After we parted, I walked northeast into a wealthier neighborhood for several miles. As I stood waiting for a light to change, I noticed a vacant lot—large enough for a building that could house hundreds of people—full of gravel and weeds, surrounded by a barbed-wire fence.

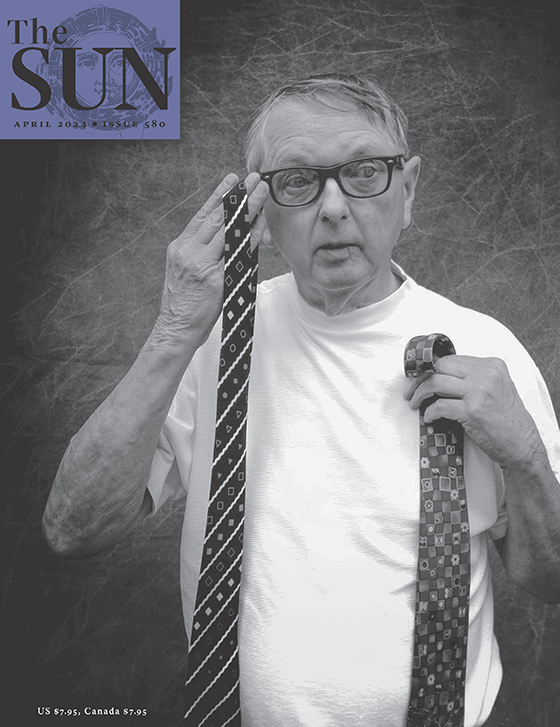

Wendy Liu

© Chandler Abraham

Cohen: Some of the ideals that created Silicon Valley were rooted in notions of the 1960s “counterculture.” What do you think that word means now, given how pervasive the technologies it produced are and how they’ve shaped popular culture?

Liu: The counterculture now is entwined with technology. Many people who think of themselves as part of the counterculture have made a lot of money from tech. There isn’t as much of a divide anymore between the counterculture and the popular culture. You can have something that calls itself “counterculture” but is still sponsored by a billion-dollar company. People—especially in this city—just aren’t as suspicious of power and capital and corporations as the original counterculture was. It’s a strange time.

Cohen: There’s also the idea of “disruption” associated with Silicon Valley. What do you think that word means now?

Liu: These days, that term is mostly associated with the smaller start-ups that are trying to revolutionize everything. And sure, some of these start-ups do have interesting technology. The problem is, it can be so lucrative to disrupt existing structures that anything framed as disruptive finds it easier to get funding. And a lot of disruption is actually quite bad for people. There’s often not enough thought as to what’s being disrupted and for whom. Disruption for its own sake is celebrated—and not just in tech. Other industries are using the same rhetoric. I recently saw an ad for a restaurant in this city that said something like “We’re rewriting the rules of hospitality, disrupting the restaurant industry.” It’s silly.

Some might say disruption is supposed to happen in the free market when companies are competing against each other to offer better solutions. It’s just the mechanism by which corporations deliver us better goods and services. That’s true. But what are the better goods and services being promised? Who gets to decide what’s “better”?

Cohen: What would be an example of good disruption?

Liu: There’s a version-control software called Git. It’s a decentralized, open-source product that allows people to collaborate on software development. When it came along nineteen years ago, it was a whole different paradigm from the more centralized version-control software people were using. Now it’s the dominant paradigm. New developers are expected to know Git. The developer platform GitHub sold to Microsoft for several billion dollars.

Compare that with disruption in consumer goods. We now have self-driving cars: Cruise, Waymo, Zoox. That’s a paradigm-changing technological advance, but it’s under the control of massive corporate entities: Zoox was acquired by Amazon, Waymo was created by Google, and Cruise is owned by GM. [Cruise suspended all driverless operations in the US in mid-November of last year.—Ed.] These companies are betting that people will focus on the disruption part and not think about the fact that these corporate players stand to gain a lot and are consolidating power.

What if self-driving-car technology were released in a more decentralized way, as something that you could install in your car, where you’d have some control over how it went? That’s a very different kind of disruption. Instead none of us has any power over these cars. If you’re on the road and you see a self-driving car stopping randomly or driving dangerously, what are you going to do? You can’t just knock on the window and talk to someone. A company controls it. At best you’ll call a customer-service helpline. You as a citizen have no say. There’s no democratic debate. When we talk about disruption, we need to ask: Who is controlling the actual technology at stake? What are they trying to do with it, and what kind of power can they accumulate through owning it? And what possibilities for this technology are being foreclosed by this method of ownership? These self-driving-car companies often position their products as an antidote to human error: people get into car accidents, they make mistakes, they drive drunk, so self-driving cars will save lives. Sure, but better public transit is another solution. Many cities have much more robust transit systems than San Francisco. It’s not really an accident that so many of these cars are here.

Cohen: So a beneficial disruption would give people some control over the services that are being provided?

Liu: It’s tough to say exactly what constitutes a beneficial disruption. Things happen in a particular political and economic context, not in isolation. There are a lot of upsides to more people having access to smartphones and computers, for example. Almost anyone is able to send an email or access the internet now. But, of course, we all know the downsides to that as well.

Part of me is still optimistic about technology and democratizing certain aspects of it, but it feels fraught right now. The people in charge of the technology can have nefarious intentions that will not be immediately obvious to the people who are receiving it or implementing it.

Cohen: Reading your book, I got the sense that what cracked things open for you was understanding how labor issues have applied to Silicon Valley.

Liu: Once I saw the development of new technology in class terms—how a particular kind of technology gives one group of people power over another—it started to feel more sinister. In the past I was really naive and cavalier about it. I thought that, obviously, technological development is good. I felt superior to people who didn’t understand how to use tech. But history tells us that in a capitalist system, technology’s function is to control a group of people—that is, workers—and get them to produce more. Once I understood that, it was hard for me to look at modern-day tech companies and not see through the veneer of their rhetoric about how they were democratizing, revolutionizing, disrupting. It became clear that these companies’ mission statements could not be taken at face value. The people who work at these companies might believe they’re making the world a better place, but the history of technological development under capitalism is that this technology gets used to discipline and extract more surplus value from labor. That’s just the reality of it.

People in the tech industry like to claim their opponents are Luddites—reflexively anti-technology. But the real Luddites in nineteenth-century England were trying to prevent their work from being devalued by technologies employed by management.

Cohen: Recently there have been a number of strikes, or threatened strikes, from actors, writers, UPS workers, Kaiser Permanente employees, hotel employees. Do you think something similar could happen in tech?

Liu: It depends on what we think of as tech. For me, the idea of Amazon warehouse workers striking would be more exciting than a strike by, say, software engineers. There have been some labor uprisings among engineers and other better-paid tech-industry workers in the last few years, like the walkout at Google, the Project Maven controversy [Google staffers refused to participate in developing AI software to improve drone targeting—Ed.], and similar situations at other companies where people didn’t want to work with the military. But many tech workers just want to work on cool projects and collect their paychecks. It’s way easier to do that than it is to advocate for lasting change. And some are on work visas and would have to leave the country if they lost their jobs. There are a lot of reasons why people don’t want to rock the boat. Many workers are paid really well, and that money buys a kind of ideological submission. It’s just so much easier to believe your company is doing good, or that leadership will make the right decision eventually, if you’re making half a million dollars a year.

People in these well-paying jobs could act out of solidarity with workers in other parts of the chain—Uber software engineers could strike in solidarity with drivers, for instance. But it’s hard to imagine that turning into a broader labor movement. When I first moved here in 2018, I was a lot more excited about the possibility of organizing corporate tech workers, because a walkout at Google over the company’s handling of sexual harassment had just happened, and it seemed like a whole new world was around the corner. But then things settled down, and with all the recent layoffs, it doesn’t feel like there’s much potential for anything.

Cohen: Is it even possible for contract workers like Uber drivers to organize?

Liu: There’s a lot they can do outside the realm of traditional labor law, and I think that is both a weakness and an opportunity. In the UK, couriers for Deliveroo [a food-delivery company—Ed.] are not bound by anti-union laws precisely because they aren’t classified as employees as such. So they’re able to go on strike at will, whereas a lot of the traditional unions require a 50 percent vote to go on strike. So these newer union-ish entities are able to move faster.

As you were saying, we are in a moment where a lot of strikes are happening, and many have similar foci. Whether it’s the Writers Guild, actors, hospitality workers, or healthcare workers, a lot of their complaints are about technology replacing people or making them work faster or harder. The workers aren’t anti-technology, but they are recognizing that, when used by management, technology often has the effect of disempowering workers or making their lives more difficult. And it doesn’t have to be that way.

Right now technology is synonymous with these big corporations and how they want to use it. It’s not really possible to work on socially beneficial technology for its own sake without considering their outsized role, because you’ll end up having to get funding from them or partner with them in some way.

Cohen: In a recent review of two books about Silicon Valley, tech writer Ben Tarnoff wrote that the worldview of “disruption” contains a “particular theory of history: that technology makes the past, along with the forms of expertise that arise from studying it, irrelevant.” Do you think the notion of progress in technology means you leave the past behind?

Liu: People who have the power in the tech industry love to tell the story that whatever form of disruption they’re selling will make everything else obsolete. It’s convenient for them to believe this, because then they can dismiss any criticism as belonging to this soon-to-be-obsolete order. Their fancy new technology will make wealth so abundant that any concerns about distribution or fairness or equality will become irrelevant. This is how you think if you’re someone like Elon Musk—or Paul Graham, who was very influential for me when I was younger and learning how to program. He’s a programmer who sold his company to Yahoo in the nineties and through that became a highly influential start-up investor. His view is that technology magically creates abundance, and critics of technology simply don’t understand that. It’s a way of saying that only people who are working on some technology can decide what’s good or bad about it, a philosophy which people in the tech industry are, unsurprisingly, often seduced by. And I just don’t think it’s true. The paradigm changes that these companies promise won’t actually make everything else obsolete. People in the tech industry like to claim their opponents are Luddites—reflexively anti-technology. But the real Luddites in nineteenth-century England were trying to prevent their work from being devalued by technologies employed by management. It wasn’t a mindless anti-technology rampage; there was a class war happening, and they needed to fight back.

There are small-scale efforts to develop technology in a way that’s not just grist for the mill, but most of what we think of as technological development is happening in conjunction with big corporations. I walk around the city, and I see all these self-driving cars, I see all these billboards, I see all these start-up offices, and I think, What pieces of technology are being developed outside of this world, in the margins? I’m sure there are some, but it feels so paltry in comparison to what’s being developed by capital. It’s not enough. The thought of the increasingly hollow world being constructed for us by these soulless corporations makes me deeply unhappy.

The sources of optimism I do find come from the labor movement. In this very city, in 1934, there was a general strike. Sure, the world was very different then—the industrial composition of the city was totally different—but I look at photos taken during the strike, and it’s kind of shocking how familiar everything feels. Maybe they wore different hats and drove different cars and held different jobs. But people are still people, you know? It’s heartening for me to think that, at one point, in this city, it was possible for a general strike to happen, and that it transformed people’s attitudes toward work and their bosses and what the world could look like. I find inspiration in that, and the recent wave of strikes makes me think about the potential for similar moments of collective unity today.

But right now technology is synonymous with these big corporations and how they want to use it. It’s not really possible to work on socially beneficial technology for its own sake without considering their outsized role, because you’ll end up having to get funding from them or partner with them in some way. It’s a depressing thought, but it’s true. I don’t think there’s any way of changing this state of affairs purely with technology itself, no matter how innovative it is. There would have to be some sort of political change involved.

Cohen: In his recent book Palo Alto, Malcolm Harris talks about how even if Steve Jobs and Bill Gates had never existed, what they created would inevitably have been created by someone else. Do you think that’s accurate?

Liu: I think Harris is spot on. As a culture we think the story of these famous individuals is inseparable from the story of the technology, but it really isn’t. Harris isn’t saying these people didn’t work hard; he’s not saying they weren’t smart or capable. He’s saying there was a space carved out for someone—whoever it may be—smart and capable and hardworking to seize on a particular technology and help it take off. This is something all start-up founders implicitly understand. When they pitch to investors, they typically have a slide that goes like, “Here’s why the moment is right: this technology just got developed,” you know, “semiconductors just got this much cheaper,” or, “the internet has connected all these people.” There are historical, political, and economic reasons an idea takes off. Any start-up founder knows that if they can’t get investors for their idea, someone else who can will probably see that opportunity, and that person will get credit for developing the new technology.

What this means is that the ability of these people to grow their companies to such massive scale can’t depend solely on their personal characteristics and abilities. To a large extent, they were simply in the right place at the right time—they were able to convince investors to invest in them and employees to work for them. It also helps to be really good at creating a media narrative and taking credit for other people’s work. Look at Elon Musk: he had a habit of coming along right when a company was about to take off and then taking credit for it, even when he wasn’t there at the beginning. So much of what we credit him with was the hard work of a lot of other people. He sells the image of himself as a genius hacker in a lab, as if he personally hand-made the first Tesla car or SpaceX rocket. In reality his role in these things is mostly coordinating, getting people together, and being a prominent figure who attracts investors and employees. He’s good at that, yes, but it’s not the same as actually inventing all these technologies. The same is true of everyone we associate with technological change and disruption: the main thing they’re good at is taking credit, even if they had very little to do with it. And I think that’s worth remembering. We don’t have to bow down to these people. They’re not so much better than us.

In a similar vein, Harris tells the story of how Leland Stanford, the founder of Stanford University, attained political and economic prominence in California. He was kind of just a dumb guy who was really good at taking credit for other people’s work and got lucky. That’s a history we should be aware of when we think about the people whose names adorn buildings in San Francisco today: the Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, the UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital. We end up thinking of them almost like gods, just because their name is on something. But what they’re really good at is taking credit for other people’s work. That’s not something we should value.

Cohen: There’s a mythology associated with tech CEOs that we can’t seem to get enough of. We consume books, podcasts, movies, TV series, and documentaries about Zuckerberg, Jobs, Adam Neumann from WeWork.

Liu: I think there’s something dangerous about these attempts to mythologize people. It makes them seem superhuman. We focus too much on their personalities and not enough on the historical forces that allowed them to succeed. Yes, Adam Neumann is a charismatic, interesting person, but I don’t think it’s helpful for people to watch something on TV about him and come away thinking, This guy is just really special, rather than, The moment was ripe for some company to buy up a lot of unused buildings and try to make a brand out of that.

Sometimes the illusion comes crashing down, like it did at Theranos for Elizabeth Holmes. [In 2023 Holmes was convicted of defrauding investors and sentenced to eleven years in prison.—Ed.] What’s special about her is her ability to convince a lot of rich people to give her money. I remember reading an article about Holmes in 2014, right after I had founded my own start-up. This was before the downfall—Theranos was then valued at several billion dollars, and Holmes, who had dropped out of Stanford at nineteen to start the company, was being ecstatically praised for her genius and her youth. I wanted to work for her, to be like her. These days I’m wary of media stories about superstar CEOs because they tend to make people aspire to be like them through copying their idiosyncrasies, rather than helping people understand that success has more to do with the needs of capital at any given moment.

An individual has only so much power. Sure, the success of your start-up has to do with how good you are at raising money and building technology, but it has a lot more to do with market conditions. What are investors trying to build? What technology exists? What sort of people can you hire? Mark Zuckerberg didn’t emerge in a vacuum. Certain things were receding, and others were emerging, and the technology that would succeed would largely be determined by the needs of the moment. I mean, these people are certainly interesting, so I understand why there’s so much attention paid to them, but to me what’s more interesting is how they interact with larger economic forces.

Cohen: You mentioned the “needs of the moment.” Getting to this restaurant, I saw a lot of people in need on the streets of the city. The income disparity here is enormous. How is it that city or local governments can’t hold some of these companies accountable for contributing to such disparity? I understand that part of the answer is money—you’re not going to make any money by helping homeless people. But there’s a moral imbalance here.

Liu: I actually used to live just a couple of blocks away from here. Mission Street between Sixth and Fifth is one of the most depressing blocks in the city. The people there don’t get adequate support for mental health or substance issues, and the result is really dire. It feels like this city in particular, and maybe America as a whole, has an ideological need to treat these things as failures on the part of the individual, when really it’s a systemic issue that has to be solved on a collective level. The flip side of that is if someone succeeds, then that success is all about them, and they don’t owe anything to anyone else. That’s why we have so many billionaires in a city that also has so many homeless people, and why a common response to that is to believe these unhoused individuals are just bad at living in society, and we need to get rid of them. Politically inclined tech billionaires in this city love to put money into local efforts to “clean up homelessness” and “get tough on crime”—conservative approaches that are framed as compassionate but are really rooted in these rich people’s desire not to have to personally see poverty in their city.

There’s something deeply disturbing about the combination of incredible wealth and corporate power and incredible need on the streets. There’s a company based here called Pacaso that claims to be “democratizing” second-home ownership. It’s really just a fancy time-share: you can pay half a million dollars to “own” one-eighth of a second home in Tahoe, which you then get to use for one-eighth of the year. What exactly is being democratized here? That’s a big trend in the industry—using the language of social justice to make employees feel like they’re working on something mission-driven, even when the thing they’re “democratizing” is, quite frankly, an unnecessary luxury, particularly in this city where so many people don’t even have first homes. There was a Pacaso billboard in my old neighborhood a few years ago, and I would sometimes see homeless people pushing their shopping carts past it, which is such a perfect image of this city. Sometimes when I walk around, I have to ask myself, Is this real? It’s like being in a dystopian video game.

Of course, people who have made money from tech want to believe that their success has nothing to do with the city’s problems. Wealthy tech people love to blame the city’s housing crisis on progressives and their support of rent control, suggesting that what we really need is for developers to build more luxury housing. Never mind that a lot of these luxury units are totally empty right now! Their narrative is that the city is struggling because the enemies of progress are stuck in the past, preventing technology from being unleashed. Their vision for the city is to get rid of the undesirables and build a playground for the elite. That vision is unfortunately pretty compelling to many who live here and are disturbed by what they see.

I feel lucky to have found a community with similar values to mine, because there are a lot of people in this city who don’t care, who don’t see the connection between their extreme wealth and the misery inflicted on the rest of the population. They think we just need to teach homeless people to code or turn them into Wi-Fi hot spots or something. (That’s a real thing, unfortunately.) I suppose it’s better than busing them to containment camps. But any solution that doesn’t actually redistribute power is not going to work.

Cohen: Silicon Valley is a concept as well as a place: the belief that all you really need to succeed is an idea. Do you think that belief is overriding the other problems with the model?

Liu: When people talk about creating another Silicon Valley, they mean giving people the ability to create a lot of wealth out of a very small start without much state support. That’s a positive way of looking at it: seeding an innovative technology that grows to become a global player. The negative sides are often ignored or just not seen as a problem. For example, a lot of these companies rely on underpaid labor to some degree. Look at the way gig-economy companies like Uber and DoorDash rely on workers being classified as “independent contractors” to save on labor costs, or the way companies like Google [Alphabet] and Facebook [Meta] that rely on user-generated content end up subcontracting content moderation to places with lower labor standards. They’re also building intellectual property out of technology that was developed by researchers all over the world—they’re taking this communal effort and commercializing it in a way that makes it hard for anyone outside of that company to use it.

Whenever there’s a call for a new Silicon Roundabout or Silicon Slopes [tech centers in London, England, and Lehi, Utah, respectively—Ed.], its proponents are seeing only the good side, not what makes this paradigm harmful. People who have bought into this dream will spend their lives building something only to see their hopes dashed by venture capitalists, who have to prioritize their own bottom line. Once in a while you’ll get that rare start-up that succeeds. But the vast majority fail. People associate Silicon Valley with success and glamour and wealth, when what actually comes out of this place is a lot of failure and wastefulness. When someone says, “We should build a new Silicon Roundabout,” what they’re really saying is We should have an army of burned-out tech workers who hate their jobs.

Any attempt to replicate Silicon Valley elsewhere is also misguided because there is something special about the Bay Area. Silicon Valley’s close ties with Stanford, for example, aren’t something that can just be magically reproduced somewhere else. It takes a lot of historical forces as well as luck.

Cohen: I’m going to read you a quote from Sam Altman [the CEO of OpenAI, an artificial-intelligence firm whose value since releasing its ChatGPT product has risen to nearly $90 billion—Ed.] from a profile written about him in 2016, when he was still at the start-up accelerator Y Combinator (YC): “Democracy only works in a growing economy. Without a return to economic growth, the democratic experiment will fail. And I have to think that YC is hugely important to that growth.” How well do you think that statement has aged?

Liu: I find it revealing in a way that’s uncomfortable to think about. It’s very consistent with his worldview. Around the same time as that profile, he said in an interview that we had to be ready for a world with trillionaires, and that we’d have to allow that to happen to drive society forward. This belief is fully consistent with the idea that unleashing the power of tech corporations will magically create abundance for all. It avoids all discussion of distribution, with the implication that as long as the tech sector is growing, it’s fine. But growing how much and for whom? Is it growing so that some people become trillionaires and others get marginally better Apple Watches, while the lives of the people at the bottom get worse? My personal concern is with how life is changing for people in concrete terms, not whether the economy is becoming more valuable in abstract terms.

Cohen: OpenAI is both for-profit and nonprofit at the same time. How is that possible?

Liu: I looked into the corporate structure when I was writing a piece about OpenAI. The cap on return for investors is a hundred times the original investment. They can still make a huge amount of money. I think the hybrid nature is a marketing technique designed to deal with people’s concerns about some corporate entity having control of this powerful new technology. I don’t think the cap on investment return will make it better. It’s empty corporate window dressing.

Cohen: Last year Altman, along with a number of other tech-industry executives—Musk, Zuckerberg, and Sundar Pichai of Google, among others—went to Washington, DC, for a meeting with lawmakers, and they nearly all agreed that AI needed to be regulated. Is that window dressing?

Liu: I think that’s their way of saying, Hey, we’re here to stay. We’re going to be powerful no matter what. But we’re willing to work with existing power structures a little bit. It still posits a world where AI is being developed by big companies for whatever purposes they want. They understand there’s a lot of criticism and calls for more regulation, and if they are able to get ahead of that and at least seem like they’re working with regulators, they can preserve their roles as power players. Plus they may get a seat at the table when the rules are being written and make it harder for anyone to challenge them. None of what Altman does makes me feel good about the future. It’s all deeply upsetting.

When I was working on a start-up, my cofounder had an email exchange with Altman while he was still at YC. We really wanted him and Paul Graham and people in that circle to believe in us. There was a little bit of hero worship going on. I think a lot of young technologists see the YC model and Sam Altman’s view of the world as the right one, and they either don’t understand or just don’t care about the ramifications. These people envision a technocratic world where only those who have technical expertise get a say, and as long as wealth is being created and the economy is growing, it doesn’t really matter what anyone else thinks. It’s hard to argue when the debate is framed as binary: you’re either pro-technology, pro-progress, and pro-wealth, or you’re just a Luddite who doesn’t understand. Altman is promoting this message that AI is the future, whether you like it or not. He’s positioning himself as a neutral arbiter of what that future will look like, as if the fact that he happens to be running an AI company were irrelevant.

In Silicon Valley the extreme wealth disparity is capturing part of what America is supposed to be like: this idea that you can start from nothing and become a billionaire. Then there’s the reality of living in the city, which is that a lot of people are much closer to being homeless than to becoming billionaires.

Cohen: There are things that can be genuinely beneficial about AI. There could be enormous benefits for medical research. Los Angeles has been using AI to predict which low-income residents are at greatest risk of falling into homelessness.

Liu: I’m not saying, This technology is purely evil, and there are no good uses of it. I’m critical of the broad direction we’re going. I’m looking at the full context of it. If a company comes out with a useful consumer product but also uses it to gather data for questionable purposes, that caveat matters. With OpenAI I’m particularly worried about their present and future partnerships with corporations that are trying to reduce labor costs, which will likely degrade the quality of services for consumers in order to deliver better returns to the shareholders. OpenAI can say to businesses, Use our product to replace some of your staff, and you’ll save money overall. OpenAI gets some money, and people will lose their jobs. What’s OpenAI going to do for all those people? They’re not going to accept responsibility for that. That’s not in their purview. Seeing that kind of direct transfer of money away from labor and toward capital, of which OpenAI is a small piece—that is the scary part.

I think technology like that should belong to the people. It’s our shared international heritage. Our current intellectual-property regime treats it as the property of one company, but I see these technologies as part of a scientific commons that should rightfully belong to all of humanity. Think about what OpenAI’s technology is built on: there’s a mountain of data that it gets for free. It’s parsing Wikipedia articles. It’s parsing Reddit posts. It’s parsing printed books—often material that was created long before OpenAI came along and hired people to build large language models on top of it. We should be very upset that a company decided this treasure trove of humanity belongs to it, and that it has the exclusive right to maintain this software and charge money for it.

AI can actually improve people’s lives, but for the most part it’s going to be used by corporations in a way that does not benefit us. Ultimately it will get people laid off and will make our experiences with customer support even more infuriating. It’s being foisted on us without our control.

Cohen: What would a decentralized version of AI look like?

Liu: We don’t have the infrastructure for it. It’s a given that anything large enough in scale will be owned by some company somewhere, probably one that has unfair labor practices. OpenAI subcontractors in Kenya get something like two dollars an hour to clean up data. It’s hard to imagine an alternative. I think of cooperatives and open-source software and other noncorporate models, but I don’t know what those would look like on the scale demanded by AI.

These are big questions: What do we want society to look like? How do we want things to be distributed? How should decisions be made about what gets built? The answer to all of them is: it’s complicated. But the short version is: something other than what we have now, because it’s mostly just the people who have a lot of money who are happy with the status quo. I used to think that if I just believed a little bit harder in the tech industry, these problems would magically sort themselves out. But companies don’t have the right incentives. It’s made me lose faith in the world the way it is. I try to counter that by having faith in people and their ability to change. Otherwise I would just be miserable all the time. I kind of am. [Laughs.] But there’s a little optimism around the edges.

Cohen: I wonder about younger people who have grown up with these technologies: Will they just accept that this is how things are supposed to be, or will they form a new counterculture?

Liu: When you grow up taking a certain technology for granted, it’s really easy to think, This is just how it is. Take smartphones: They make you feel like you don’t have control over the technology. You’re just the user. You can move the apps around on your home screen, but you can’t really change much about how they work behind the scenes. It’s a big jump from using an iPhone to developing an iPhone app. Most people’s computer literacy is limited to being a consumer of the technology. That gives more power to the people who work for these big companies and understand how these technologies actually work.

In terms of a counterculture for young people, I guess there are the doomers, who are nihilistic and predict possible human extinction. But then there are people who would be willing to work at a defense company like Lockheed Martin or Raytheon. I’m curious to see what sort of generational tendencies are produced by the fact that a lot of young people grew up on the internet, but I also wonder how similar this generation will be to older generations. Malcolm Harris is really against generational analysis; in his book about millennials (Kids These Days: Human Capital and the Making of Millennials), he tries to connect them to older generations. There’s a lot this generation will experience that other people have already gone through, but they will also have unique experiences because of the internet era and the advanced state of climate breakdown. They’re going to be dealing with economic precarity. Are they going to go to college and take out a hundred thousand dollars in student loans? Or are they going to try their luck without a degree? Are they going to be able to buy a house? Probably not. They’ll be inheriting a world that is on the brink of collapse.

Cohen: Those are some massive differences.

Liu: For sure. Someone who’s born today will inherit a very different world, but there will also be things that are constant across generations. Maybe an increasingly large percentage of people will have difficult lives, but there will always be some who will glide through without much trouble because of their privilege. These disparities make any kind of generational analysis difficult. I remember reading all these articles a while back about millennials and how they couldn’t afford to buy houses and had bad jobs and weren’t making any money. That didn’t ring true for me. A lot of people I knew here had great jobs. It’s not that those articles were wrong; I was just looking at a very unrepresentative sliver of the millennial population, and that made it hard for me to understand what was going on. There are generational trends, but there are always some who buck the trends, because of the way the economy is set up and the way wealth is distributed.

Cohen: If you’re no longer working in tech, and you see a lot of things wrong with this city, what makes you stay?

Liu: I’ve built up a good community here. And I care about what’s going on in the tech industry. It’s depressing, but it’s also important to me. I like being able to overhear people in Patagonia vests talking about their investments and whether something is an annual recurring-revenue product versus a monthly recurring-revenue one. I have a hunger to know what their lives are like. The people who make these decisions about what gets funded and where the money goes—what drives them? I read articles by venture capitalists for venture capitalists because I want to know how they talk amongst themselves. As a writer I want to depict a world that is closed off to most of us, and do it in a way that comes from a place of understanding, as opposed to relying on stereotypes.

Cohen: The racial diversity in the Bay Area combined with the disparity in wealth seems a uniquely American quality. It reminds me of something else Malcolm Harris wrote: “If California is America’s America, then Palo Alto is America’s America’s America.”

Liu: It’s like [French postmodernist] Jean Baudrillard said: “Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real.” In Silicon Valley the extreme wealth disparity is capturing part of what America is supposed to be like: this idea that you can start from nothing and become a billionaire. Then there’s the reality of living in the city, which is that a lot of people are much closer to being homeless than to becoming billionaires. And everything’s privatized. Even the parks are funded by tech companies.

A few blocks north of here, there’s a fairly pointless gondola that takes you from street level up to Salesforce Park, and if you go up a bit more, you arrive at Salesforce Transit Center. It’s this dream of a world where corporations run everything, and if you try really hard and get lucky, you might be one of the few people who work inside one of those high-rises, wearing a lanyard or a badge over your Patagonia vest. But if you aren’t, you’ll end up on the street. That seems key to what it means to be an American: to know both of those realities are possible and to pretend there’s no connection between them.