My older brother came home from work one night and announced that he was doing so well at his Sears telemarketing job that the president of the company had invited him out to dinner. He stood in the middle of our brown-shag-carpeted living room, arms behind his back, and rocked forward on his toes. He smiled, pleased with himself. The president of Sears, my brother continued, was in from Chicago to visit the Salt Lake City store, and somebody — a supervisor, maybe — must have informed the president of the good work he was doing.

“You’re lying,” I said.

It was winter 1987, and though I was only fourteen to his eighteen, I hadn’t believed a word my brother had said for years. I sat in one of our plaid swivel rockers, the one that tipped easily because a leg was broken, and he said to me, “I’m not lying. I’m not.” He turned to our mother. “I’m not,” he insisted.

My brother was wearing an outfit that my mother had helped him pick out and purchase: a yellow T-shirt with fluorescent squares across the chest and cream drawstring pants. She’d done this in the hope that these cool new clothes might help him fit in better in high school. My brother had been teased all his life, and things were only getting worse for him now that he was a senior. He didn’t seem to belong anywhere. The clothes, though, looked quite different on him than they had on the mannequin: the T-shirt too tight around his stomach, pants pulled up above his waist, his white tube socks exposed at his ankles. I had often wondered if we were really brothers — Jon with his straight blond hair and blue eyes, and me with my dark, kinky hair and brown eyes.

“Marc,” my mother asked me, “why do you think he’s lying?”

“The president of Sears? Taking Jon out to dinner?”

“Well,” she said, “he’s doing a good job.”

“Yeah,” said my brother, pushing his thick, square glasses up with his index finger. “I’m top salesman.”

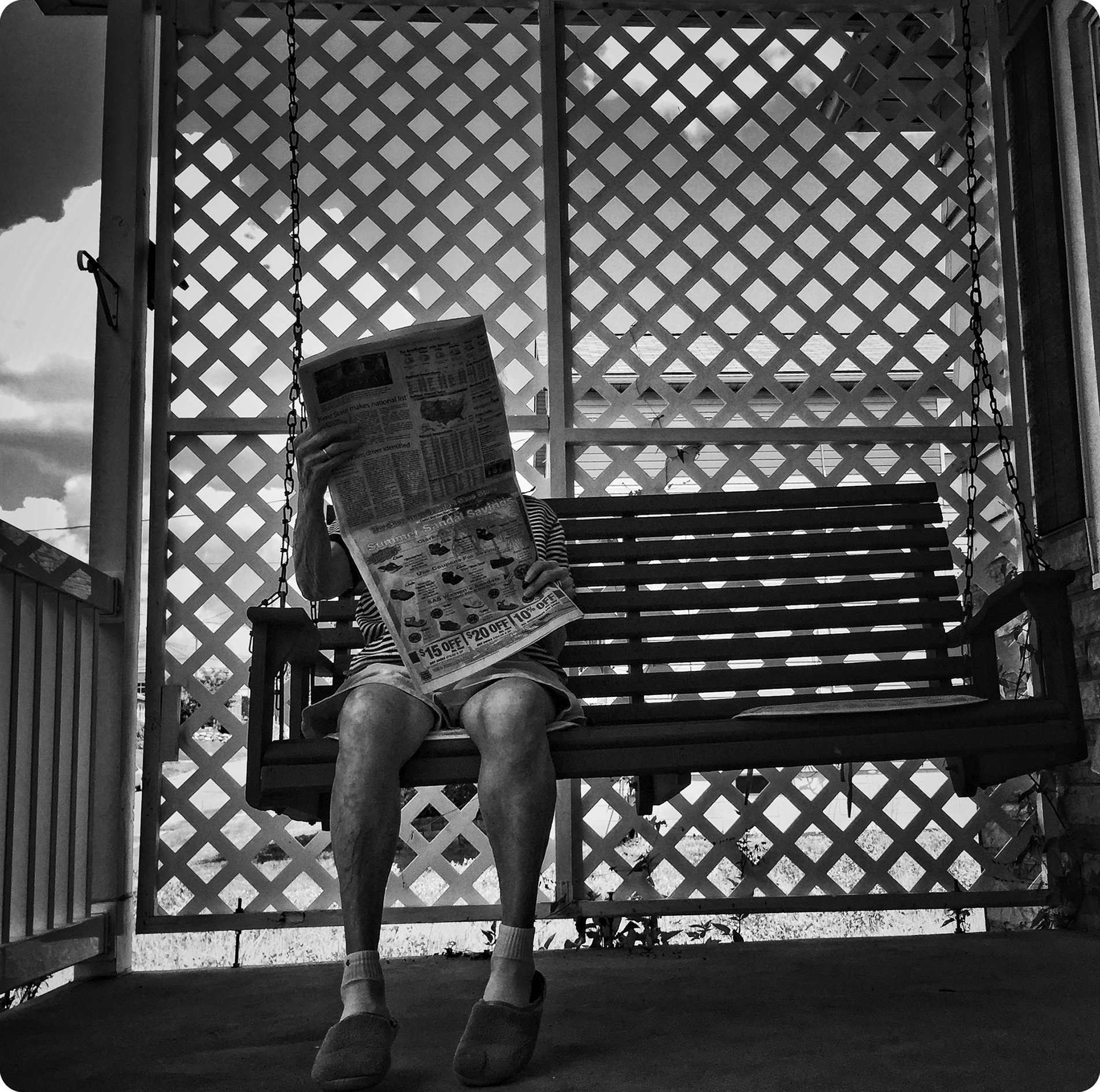

In the kitchen my mother pulled out the typewriter and placed it at her spot at the table. Then she had my brother sit next to her to relay the details for a write-up to place in the church newsletter and an entry for his journal. She slid her glasses down her nose and looked every bit the elementary-school teacher she was, with her permed brown hair, Christmas sweater, and Christmas-tree clip-on earrings. I leaned against the door frame between the living room and kitchen and asked, “Are you going to have him draw a picture, too?” We had done this as kids, telling our mom about big life events so she could write them down in our journals; then we’d illustrate the scene in crayon.

“Marc,” said my mother, “don’t you have something better to do?”

“No,” I said.

“Well, find something,” she said.

A few days later a limo pulled up to our house.

“Is el presidente coming in to meet us?” I asked.

My brother stared at me. “No,” he said, elongating the o. “The limo is taking me to the restaurant to meet him.”

He stood at the front door in a suit and trench coat, both a little too long. At five foot four, my brother often reminded me of a child playing dress-up. And he’d slicked his hair back — a style I’d never seen on him. Usually he brushed his hair straight down over his forehead, his bangs forever uneven.

“Marc,” said my mother, “stop bugging Jon.” She got up from the couch, where she’d been grading papers, and hugged my brother. “We’re so proud of you.”

My brother posed in front of the door, our mother’s favorite spot for photos.

Later that night, the lights of the limousine turning around in the street lit up our front room and moved across the wall. I was sitting in the dark watching the small television perched on the ledge of our stone fireplace, and I got up to part the curtains and watch as the driver opened the door for my brother. Jon stepped out of the limo and climbed the steep driveway. Then we all sat around the kitchen table — my mother, my father, and I — to hear Jon’s report about his dinner with the president of Sears. The restaurant, Jon said, was called the Roof, and it sat atop the Hotel Utah — Salt Lake City dining “at its highest level.”

“Yes,” said my father, “I know that restaurant. Pretty fancy stuff.” My father leaned forward for the story, arms folded on top of the table. His tie was loosened, the collar of his white dress shirt unbuttoned, and his sleeves rolled up. He traveled all over Utah selling books to schools and libraries and had just returned from a business trip. I couldn’t believe that my father was also buying Jon’s story. I was sure that my sister would have sided with me, but she was away at college.

My brother told us that he and the president of Sears had a spot against the floor-to-ceiling windows on the west side, overlooking Temple Square and the Christmas lights. They both ate the prime rib. The president of Sears was staying in a suite with a grand piano at the Little America Hotel. Not that Jon had seen the hotel room, but the president of Sears had told him about it. My brother told us all about the president, his four children, and what problems he was having with each one. And Jon told us how, in front of the hotel, as the limo driver was opening the door for him, a crowd had gathered on the sidewalk to see who he was.

“What are you looking at?” my brother told us he’d said to an onlooker.

“Jon,” my mother scolded, “why would you say that? Who did you think you were?”

I decided right then what had really happened: My brother, with his paycheck, had rented a limo and eaten at a nice restaurant by himself. Later that night I told my mother that this was what I believed, and I was relentless in making sure she knew it. In the weeks that followed, I realized my mother had her doubts, too. She questioned my brother almost daily about his dinner with the president of Sears. I would be in front of the television, and I’d hear her in the kitchen with my brother, rechecking the details of his story, until one night I heard my mother gasp and say, “Jon Michael Inman, why did you lie?”

“I don’t know,” he said.

“Jon, you’ve got to know why. Why would you lie about this? Why would you lie to us and everyone?”

There was silence. I pictured my mother standing behind the counter by the sink and staring at my brother as he sat at the table with his head down over his dinner plate.

“Jon?” my mother asked again.

It wasn’t just the lying. My brother had been stealing from me since I was five years old. I had to hide my money in drawers and under the bed. He stole from everyone in the family. He stole from stores. But he seemed, for whatever reason, to steal from me the most. Whenever I told my mother that my brother had stolen my money, we’d go through the same routine: she’d ask Jon if he’d done it, he would say no, and then she’d ask me if I hadn’t lost the money or misplaced it or spent it.

“No!” I’d shout. “Jon stole it.”

“You’re sure?” my mother would ask.

She would always explain away Jon’s behavior: He had “impulse” problems. He didn’t understand consequences. I didn’t understand why he couldn’t just stop stealing from me or why my mother believed him despite his history.

Then there were the fires. When I was five or six, I followed my brother around one day while he set different parts of the neighborhood on fire. First he lit some leaves beneath a patch of trees in what we called the gully. We watched from down the street as smoke began to thicken. When a neighbor came running, we left. At another house Jon again lit leaves on fire, and from our backyard we watched as neighbors formed a bucket brigade to stop the flames from spreading. Other times he found hair-spray or spraypaint cans, whacked the nozzle off, and lit the continuous stream of flammable liquid with a long match or lighter. He was often contemplating if there was anything nearby that could be set ablaze.

By the time I was nine years old, my parents were putting me in charge of my brother while they were out. “Tell us what Jon does while we’re gone,” they said. I was to make sure he didn’t take the empty mason jars from the basement and hurl them into the street. Along with fire, my brother loved the sound of breaking glass. He seemed to enjoy chaos in all forms. I thought it was unfair that I had to be my brother’s keeper. I just wanted to be the younger brother in a normal family, and Jon, I thought, was keeping us from being normal.

Here’s what I know now about my brother that I didn’t as a boy: His first few breaths of life were labored and gasping. He was born premature and in lung distress in 1969. No one showed him to my mother. The doctors soon informed my parents that my brother would live a few days at the most, and said that if they wanted to give him a name and a blessing, they should do so now.

My family is Mormon, and when Mormons give a newborn a name and a blessing, a group of men, usually family members, circle around the baby in church, their outstretched arms radiating from the infant like wheel spokes, and then the father proclaims the name and blesses the baby.

In the hospital my parents decided to forgo the naming and give my brother a blessing only. They had suffered numerous miscarriages before they had my sister, who was two when my brother was born. My mother’s father rushed to the hospital in the rain, and he and my father put on surgical gowns and masks. With a dab of consecrated oil on his gloved fingertip, my grandfather reached into the incubator and rubbed the oil on the top of my brother’s head. Then my father reached in on the other side, and they laid their hands on him.

My brother lived, of course, but he had been without oxygen right after birth, and the doctors weren’t sure what effect this would have on his development. For the first year of his life my brother wanted to be held all day. And when he wasn’t being held, he’d just lie there. He wasn’t crawling. He wasn’t trying to walk. He wasn’t making cooing or talking sounds (though he would laugh). And he was sick all the time, coming down with horrible coughs. Antibiotics didn’t help. Doctors couldn’t figure out what was wrong. Finally my brother started receiving gamma-globulin shots in his thigh once a month. My mother thought the results miraculous. Within a year Jon was well enough to start walking by himself, having skipped crawling altogether.

My mom told me that, when Jon started kindergarten, he was reading at a fourth-grade level but was unable to write his name or use scissors. When the school physical therapist learned that my brother had never crawled, she began taking him to the school gym twice a week to teach him how, hoping this would improve his coordination. She called it “patterning.” My brother crawled around and around the tiled gym floor, waiting for something to fall into place.

By first grade, though, he still couldn’t write. If the teacher told him to copy what was written on the blackboard, he would run away. The school secretary would call my mother to say that my brother was missing, and my mother would put me in the backseat and drive up and down the streets around the school looking for him. She’d usually find him playing with a dog in someone’s yard. After some months of this, my parents decided to return my brother to kindergarten, and he went back to crawling around the gym day after day, everyone still waiting for that sudden improvement.

It never came.

Things weren’t always bad between us. When my brother was twelve, for instance, we were turning the dial on the radio and somehow picked up the next-door neighbor’s cordless-telephone conversations. (In those days cordless phones operated at frequencies available to most radios.) After that, we would listen in periodically, and one day Jon found me outside and told me that he had overheard our neighbors’ teenage daughter setting up drug deals at the convenience store down the street.

“We have to stop it,” he told me. “Nobody else will. Nobody else knows.”

These neighbors were one of the few families on our block who didn’t go to church with us, so Jon’s story about the daughter buying drugs made sense to me. I asked if we should call the cops.

“No,” he said. “They won’t believe us.”

I told him we should wait for Dad to get home, or go to the grocery store, where our mom worked as a cashier in the summer, and tell her.

“No. It’s happening right now, and we need to stop it.”

As we went to get our bikes from the carport, his hands shook spastically, the way they did whenever he heard glass break.

We arrived at the Top Stop, parked our bikes, and waited outside, eyeing every person who entered. A few neighbors said hi to us. Eventually we went inside and stood by the arcade machines, one of us pretending to play while the other kept an eye out for suspicious activity. If my brother was the one at the machine, his arms and hands shook as if it was all too much. I wasn’t totally buying his story, but it beat sitting around the house. I also desperately wanted to see a drug deal. And I liked being around Jon. He was my big brother.

That’s how it was with us. I might yell at him one afternoon for stealing from me, and that night we would lie in our bunk beds, giggling and farting or listening to Dr. Demento’s radio show. Our room is still vivid in my mind: red, white, and blue shag carpet, thick curtains with toy soldiers and cannons, and two waist-high bookcases that our grandfather had made for us.

Then I’d go to sleep and dream that the next day with him would be better.

A year after his supposed dinner with the president of Sears, my brother informed us that he had been called to serve a mission for our church. He would be going to Houston for two years. Holding the church’s letter in his hands, he rocked up and down on his toes in the middle of the living room, ready to receive our parents’ affection.

My mother quickly got up to hug him. “Oh, Jon.” She took off her glasses and wiped her eyes.

My father gave him a hug, too, then extended his hand for a more formal handshake. “Elder,” he said with a smile. Elder was the title he’d be given now as a missionary. “Sounds like we’ll need to get you some cowboy boots, huh?” He patted my brother’s back. “And maybe a cowboy hat.”

In preparation for his mission, my parents bought my brother a stack of short-sleeve white dress shirts, a few cheap suits with extra pairs of pants, and some ties from a local men’s store, Mr. Mac. A few weeks later we all loaded into our wood-paneled station wagon to drive my brother to the Missionary Training Center in Provo, Utah, about an hour away. On the left pocket of my brother’s suit coat hung a name badge that read, ELDER INMAN. My mother had Mormon pop music in the tape deck. If my sister had been in the car — she was already in Provo at Brigham Young University — they would have been singing along together.

I sat in the backseat with my brother, wondering what he was thinking. I hadn’t thought he would go on a mission. He’d never shown any interest in church. And, of course, there was all the lying and stealing. I couldn’t imagine him trying to convert and baptize people. Or did he think his mission would be like a vacation, with our parents and our aunt and uncle paying for his food and apartment and other necessities? But he and I had both heard stories of riding bikes in the heat or cold to canvass blocks and blocks of houses, knocking on endless doors with annoyed or uninterested people behind them, the odd food served by church members who had you over for dinner.

My brother looked out the window as we passed Point of the Mountain, halfway to Provo. I studied him, wishing I knew what he was thinking.

“Hey, Jon,” I blurted. “Guess what?”

He turned to look at me. “Are you gonna say, ‘That’s what’?”

“No,” I said.

“OK. What?” he said.

“That’s what,” I said, and I started to laugh. It was a stupid prank, but entertaining to me.

“Mom!” Jon hollered. “He’s doing it again.”

My mother turned her head. “Marc, stop it. Do we need to do this today?”

But I couldn’t help it. It was what had passed for conversation between Jon and me for years. And I had always hoped that at some point he would start beating on me or at least punch me in the arm, the way big brothers did on television. He wasn’t like that, though. I could have tried to accept this, but instead I blamed him for it.

At the Missionary Training Center we sat in an auditorium and watched a short film about Jesus and missionary work. After the film ended, the other soon-to-be missionaries — all in their dark suits and white shirts like my brother, some crying, others acting like it was no big deal to leave for two years — exited out one side of the auditorium, and the families left through the other. My parents hugged my brother and told him again how proud they were. I think they were expecting him to return a man — or, at least, someone who wouldn’t lie about having dinner with the president of Sears.

“Hug Marc, too,” my mother said. “Even he’s crying.”

And I was, because I wanted to see Jon transformed into a big brother who would talk to me, guide me, give me brotherly advice, the way my sister’s boyfriend once had. But once my brother was gone on his mission, my skepticism took over, and I speculated that it was all some elaborate hoax. At any moment my parents would find out he was living in an apartment close to home and sending fictitious letters and doctored photos. Or maybe my brother would quit or be sent home early for lying or stealing or some other infraction.

But he stayed for the whole two years.

On the day my brother returned from his mission, I spotted him in the crowd emerging from the airplane gate, wearing his baggy missionary suit. Upon seeing our father, Jon speed-walked to him, dropping his bags in the middle of the crowd. They embraced. My brother was crying.

In the days leading up to his homecoming, I’d been thinking about a more modest possibility of a new relationship with my brother. I knew he was never going to play basketball with me or give me advice on girls, but maybe we could spend more time watching movies together and talking about comedians. Comedy was one thing we had in common, though our tastes were different: I preferred the neurotic stand-up comics, while he still thought farts were hilarious.

At the church pulpit two weeks later my brother told the congregation about his missionary experiences while our parents sat proudly behind him on the stand. The cuffs of his shirt reached his thumbs, and his tie was a bit off center and loose. He had tried brushing his hair to the side, but his uneven bangs wanted to hang straight down.

At one point he triumphantly raised a large ring.

“I don’t think y’all can see this,” he said. (He’d adopted y’all into his vocabulary in Texas.) “But this ring has a large skull on it.”

He drew out the word skull for dramatic effect.

He proceeded to tell a story about how he had converted a Texas motorcycle-gang member to the Church. In gratitude the man had given my brother the ring, saying, “You changed my life.”

My brother surveyed his audience. I sat on the padded wooden pew and thought, He hasn’t changed at all. How can he stand at the pulpit and lie like that? How can my parents believe this? How can anybody believe it? I wondered where he’d really gotten that ring.

Or maybe it was all true. Maybe there was a motorcycle-gang member in Texas now living life as a Mormon, all due to my brother. I didn’t know what to believe.

There was one story about his mission that I felt sure was true: A former missionary companion of Jon’s had reached out to my parents to tell them that my brother had been his favorite person to serve with. He said that every Wednesday they would each dip a tie in lighter fluid and set it on fire.

A week after my brother’s homecoming, I found money missing from my room, and I went to my mother. My brother was with her.

“See, he’s not different,” I said, pointing to him. “It’s starting all over again.”

“I didn’t steal anything,” my brother said, insulted. He got up and clomped loudly off in his cowboy boots. They looked like a costume on him.

“He can’t live here,” I said.

“Marc,” my mother calmly said, “are you sure Jon took the money?”

My brother killed himself on a Saturday night in November 1995, almost exactly eight years after his “dinner” with the president of Sears. He was twenty-six years old.

The next day neighbors and family friends were in and out of our house all afternoon and evening, most coming straight from church. They expressed surprise at my brother’s death, given that things had been going so well for him “working at the university,” or “selling Volkswagens,” or “being cast to play the piano in a movie produced in Poland.”

My brother, I learned, had even lied about how I earned a living, saying I was doing something with computers, when actually I was attending community college and buying used jeans out of a yellow trailer down by the oil refinery, next to the Southern X-posure strip club. And I was still living with my parents at the age of twenty-two. Maybe I should have been lying about my life, too.

When our next-door neighbors, an older couple, asked if we planned to mention my brother’s dinner with the president of Sears at the funeral, I realized that my mother had never printed a retraction in the church newsletter. Most of the neighborhood still believed he’d been to such a dinner. I imagined them saying to each other, “Jon Inman may have been odd and impulsive, but he also went to dinner with the president of Sears.”

My mother told the neighbors that we planned to focus on other things.

She used to say my brother believed the lies he told, and that was why he was so good at lying. I wonder if he practiced his lies until he could replay them in his mind like memories. If so, his dinner with the president of Sears must have been a good memory. He seemed to relive it on the night he killed himself: getting the limo, dressing up.

I learned this from a woman who’d gone to high school with Jon. That Sunday afternoon at our house she was sitting with us in the living room, wearing a long-sleeve floral dress. She told us how she had seen my brother at a Huey Lewis concert the night before. He was dressed up and had arrived in a limo, she said.

This was all news to us. I tried to imagine when and where the limo had finally dropped him off for the night. We knew he had driven his beat-up Volkswagen Rabbit to the park where his body had been found, on the mountainside above our house, in a more affluent neighborhood.

He had shot himself in the chest with a gun stolen from his roommate’s nightstand.

This wasn’t a park we had gone to growing up, but I had been there. On a clear day it offered a view of the valley: the homes, the industrial area, the dump, the oil refinery with its flames and billowing black smoke, and the Great Salt Lake. At night my brother would have seen only the lights of houses fading into the darkness of the lake. No stars would have been visible due to light pollution from the city.

My brother had been living on the west side of Salt Lake City, about thirty miles away, with a pregnant young woman whose family had kicked her out and two gay ex-Mormons. My brother had come out as gay himself after his mission. The last five years of his life had been unstable: one odd job or living arrangement after another. He’d even gone missing for a brief period.

Had my brother driven slowly past our house one last time on his way to the park? Maybe he’d even parked the Rabbit and sat out on the curb in front of the house, contemplating what he was about to do.

After this friend left, I excused myself to go to the bathroom, where I shut the door and fell to my knees, shaking and crying. I wished that my brother had been different. And I wished that I had been more forgiving and compassionate. I wished that everything between us had been different.

I was on that floor for a while.

His suicide note described how he’d never fit in anywhere. He grew tired of jobs quickly. It wasn’t in him to work his life away the way everyone else did. He listed what few successes he felt he’d had: graduating from high school, becoming an Eagle Scout, going on a mission. He said he’d hated how people had still treated him like a little kid after he’d returned from his mission. He said he had put off coming out as gay because of the Church and society. He said he had contemplated suicide before, in the eighth grade. He said he had felt free after asking to be excommunicated from the Church. And he said that now, at least, the lies would stop; the dishonesty and the stealing would stop.

I realize that I have treated his homosexuality as a footnote, but it was another part of him that I knew almost nothing about. Often, when I tell people that I had a gay brother who committed suicide, they assume it was because of our family’s religion and the Church’s teachings on homosexuality. I always say, without going into detail, that it was more complicated than that. But, in truth, I don’t know what tortured him the most.

It’s hard for me to admit that I didn’t really know my brother.

I’ve often tried to imagine my brother’s final night. Here’s what I picture: He sits in a fancy restaurant and adjusts the large rings he wore on both hands, which my dad referred to as his “sheik rings.” He has his hair slicked back, and he’s dressed up in a fancy shirt and the vest he liked to wear, the one that the police had dry-cleaned and returned to my parents. Maybe he puts on sunglasses, even though it’s a dark winter night, before stepping outside and sauntering to the waiting limo. He moves past people who glance to see if the rider is someone famous. The driver helps my brother into the car and shuts the door. My brother still wants to be seen as the limo pulls away, so he rolls down the tinted window and waves goodbye to the onlookers gathered in the cold, as if they were his doting fans. Then he rolls up the window, and he’s alone.