I don’t own a single book of poetry, and never really got over a childhood association between “poetry” and the rhyming jumprope chants we used to sing (Charlie Chaplin went to France, to teach the ladies, the Hootchie-Kootchie Dance), so it was a small miracle that I heard Robert Bly when he was in Chapel Hill.

I decided to go because I’d had a few Bly poems read aloud to me by a friend and I never noticed they were poems. Also because this same friend, who had not made an effort to see or hear any of the many speakers and attractions that had come to Chapel Hill in the two years I’d known him, was excited about Robert Bly coming.

As the small lecture hall began to fill with people, I began to get pre-lecture anxiety; hoping the reading wouldn’t last too long, that it wouldn’t be boring, and that it would dispel the prejudices a part of me clings to (poets: at their worst, a secretively smug bunch with properly sensitive eyes, tasteful reserve, and cloistered “meaningful” conversations, their quiet arrogance leaving me outside their poetry).

When Bly came in, no one cheered or stared, so when he passed by in the aisle, I said audibly to my friend, “Is that him?” He nodded quickly as if to hush me.

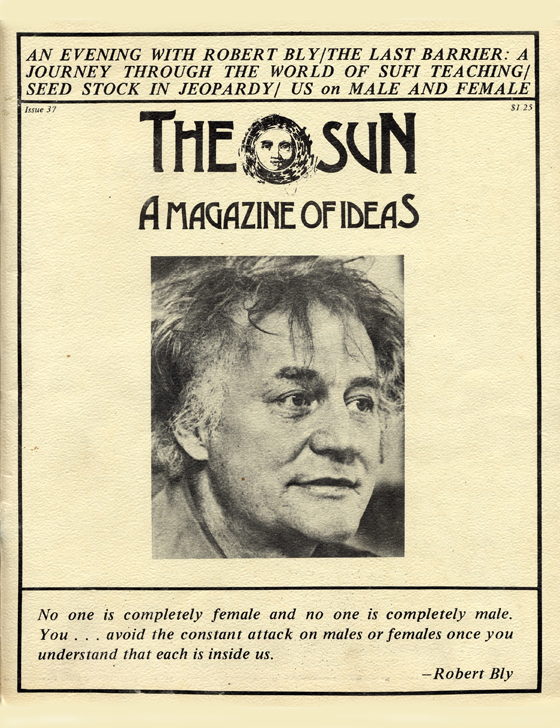

He was a big man, in his fifties, perspiring slightly, wearing a bright red print shirt and long red kerchief tie around his neck that didn’t match the shirt; I wondered if a woman had picked it out for him or if he had.

He had a dulcimer case and some books with him that he put on the floor after he sat down in a chair on the stage, the crowd still milling around.

Someone was introducing Bly when I noticed his shoes were missing. I looked for them; they didn’t seem to be anywhere. I wondered if he’d walked from the parking lot that way, wearing socks like shoes. I could see the white flesh of his big feet in worn places in his socks.

The introduction was long, and academically impressive. I squirmed, not wanting to be impressed academically.

Bly’s beginning relaxed me; he didn’t sound professorial at all — “I live on a farm in Minnesota . . . I make a living giving poetry readings . . . I have a wife and four children . . . So I’ve been out now a week earning some dough.”

He kept talking to us in this conversational tone, as if he were sitting next to you on a bus or train, and it was apparent right away he was worth listening to because he was very unself-conscious and able to strip you of whatever pretensions you came in with.

Or prejudices. Any ill-founded preconceptions I’d had about poets and poetry dropped away before Bly, as he used his body, his hands, to speak his poems, make them sound, waving his hands around musically as he spoke, a clumsy dance for him in his large, solid, bulky strength. (The first time he did this, swaying, tilting, and leaving a little finger hanging in mid-air at the end of a line, I was mystified. It occurred to me that he might be mocking us. Or maybe all poets were this deliciously undignified when they gave readings? I tried to ask my companion, who would know about these things, but got no response.)

But Bly wasn’t making fun of us, he was enjoying himself. His poems entered his conversation almost unannounced, and you were unsure whether he was still talking or had started on a poem, a seeming change in his bodily weight sometimes the only clue (he began that weightless dance with every poem).

Several times, Bly put on masks, real masks, and walked around the room with a menacing air, a superiority of presence, taunting us, as the self-assured spirit of darkness, manipulating people into every place but themselves, hissing at them, “Do you think just because you go to Chapel Hill I won’t get you?? You’re a little apathetic maybeee??”

He talked about “boy gods” he’d met (and the boy god he’d been himself), the young men who seek out enlightenment with little or no willingness to inhabit routine, or ordinariness, or to be responsible, even to themselves. (“They never keep appointments, they camp outside Zurich, in tents, can’t stay in hotels . . . and call you at two in the morning . . .”)

Like a father or grandfather, Bly told us stories all night, often through his poems, people sometimes calling out the names of favorites for him to read, and I was so moved, so pleased to have found out that the real intent of poetry is to transport us into the delicate ordinariness of the spirit: expressed by everything that you must write down, when you have no choice but to live in that burst of silent meaning that saturates one and leaks out as words, rooted in joy. (Bly: you write it down then, you don’t wait until you get home.)

Bly’s appreciative, startling eye for this: he understands and trusts that instinct, has been obedient to it. He writes it down, trusting the words that come as keys; even if some of the lines sound “bad,” he forgives himself, and so do we if he does.

Robert Bly exemplified something I’d never connected with poetry before, a simple human quality that becomes a necessity if one is to grow: moving beyond the confines of fear. His presence is never one of mystery, or unapproachable brilliance. He is brilliant, yes, but like a child’s brilliance, or a very old person’s abandonment of time, and resulting freedom.

He knows it too, and speaks of it, as part of why he is sound and healthy at 50. “I know men who are healthier at 50 than they’ve ever been before. Because a lot of their fear is gone.” He says these things the way one would mention the weather, his small talk not small at all.

Robert Bly is himself, not for show, but because it’s the kindest, most loving thing you can do for another human being. His poems are proof.