Writer, naturalist, and wilderness explorer Craig Childs is known for his love of the American Southwest and its severe, arid landscapes. An obsessive walker, he logs many thousands of miles annually, almost entirely away from official trails. He’ll carry gear and water into a so-called wasteland and immerse himself in his surroundings: the geology, the wildlife, the traces of ancient humans. He possesses a seemingly inexhaustible store of anecdotes about rattlesnakes, ravens, flash floods, blistering sun, desperate thirst, and skeletal remains. One reviewer for The New York Times described him as “a modern-day desert father, seeking transcendence in self-deprivation, solitude, and steadfast meditation on his mortality.”

Childs was born in Arizona, and his parents divorced when he was young. He grew up with his mother, whom he calls an “insatiable outdoor traveler.” His father, who brought him on fly-fishing trips, was “sort of a redneck philosopher” — a fan of whiskey, guns, and Henry David Thoreau. Childs spent his twenties roaming the Southwest, living out of a truck, and taking backcountry excursions that lasted months, a lifestyle he refers to as “tethered nomadism.” Now forty-nine, he teaches writing for both the University of Alaska and Southern New Hampshire University. He has written a dozen books. His most recent, Apocalyptic Planet: Field Guide to the Everending Earth, won the Orion Book Award and the Sigurd F. Olson Nature Writing Award. He’s an occasional commentator for NPR’s Morning Edition, and his work has appeared in Outside and Men’s Journal. His website is houseofrain.com.

I met Childs for this interview on a warm November morning at his house in Norwood, Colorado. We sat in a sunny kitchen beside a room where he had set up a treadmill desk. A replica of a saber-toothed-cat skull served as a paperweight. Outside the window, a sparsely forested canyon dusted with snow extended toward the distant Utah border.

Childs has the sturdy build of a trekker, not a sprinter. His hair is neat and his beard unkempt, and a gap between his front teeth shows when he laughs. During our three-hour talk he was energetic and animated, yet he also had a stillness about him, as you might expect of a man who has passed countless days in quiet observation of animals, plants, stones, and clouds. Rising to leave, I noticed a bulging backpack by the door. I didn’t ask Childs whether he had a trip coming up. The answer, most likely, was yes.

CRAIG CHILDS

© Ace Kvale

Tonino: Your last book was titled Apocalyptic Planet: Field Guide to the Everending Earth. What do you mean by “everending”?

Childs: I mean that the end is always happening. We think of apocalypse as a moment — a flash of light, then you’re gone — but if we study the earth’s history, we find that it’s not one moment. It’s actually a long process. In fact, it’s hard to see where it begins or ends. Like right now: evidence indicates that we’re experiencing the planet’s sixth mass extinction — a period when the rate of extinction spikes and the diversity and abundance of life decrease. Each such extinction event takes hundreds of thousands of years to play out, and it’s generally 5 to 8 million years before the previous levels of biodiversity return. So are we at the end or the beginning of a cycle? This could just be a temporary spike. The pattern could swerve in a different direction.

Look at the extinction event 65 million years ago that wiped out the dinosaurs. Some scientists say it happened just like that — kaboom! A meteorite hit the earth and sent dust and debris into the upper atmosphere, and it came raining down over the entire planet, killing anything aboveground. But it wasn’t quite so quick. The fossil record shows signs that some types of dinosaurs were still around three hundred thousand years after the impact. And there were other factors. After all, the dinosaurs had lived through other meteorite impacts in their 160 million years of existence. Why was this one so devastating? The fossil record shows a decline in the ecological health of the planet leading up to that meteorite impact. Species were already starting to die off. So it wasn’t just one moment. It was that moment, and the one before it, and the one that followed.

The earth — from core to atmosphere to magnetic field — is an organism. It’s not a set of cogs and gears. It’s a dynamic interplay of forces. Water goes many miles beneath the surface and lubricates the tectonic plates, which move and cause earthquakes and, over millions of years, send up mountain ranges. Everything is connected, like the membranes, muscles, and bones in a living creature. It’s not a machine where, when something breaks, kaboom! you’re done. We have this concept that we can break the planet. Yes, we are pouring poisons into the environment. Yes, the planet is absorbing our poisons. And yes, they are changing everything, from individual species to global systems. But unlike my car’s transmission, which recently blew up and left me stranded on the side of the road, the earth doesn’t just break.

When I look at the environment, I see a lot of problems, a lot of red flags. I see dynamics changing in ways that we can’t predict. But this is not a dead planet, nor will it be anytime soon. If you want to see a dead planet, take a look at Mars. Maybe there’s some hint of life there in a sliver of ice, but it’s a far cry from what we’ve got on earth. This planet is alive and kicking. It can absorb impacts, extinctions, alterations of air and ocean currents. I don’t mean to say the earth is just happily soaking up everything we heap upon it. It’s a living organism, squirming and wriggling. But unlike an engine, it can repair itself.

Tonino: In Apocalyptic Planet you quote Henry Miller: “The world dies over and over again, but the skeleton always gets up and walks.”

Childs: Right. Everending. Everbeginning. It goes beyond your daily life. It goes beyond who you think you are and gets into the fundamentals of how the world works.

Tonino: I’ve certainly heard, both in the media and in conversation, that a cataclysm is just waiting to happen. Are we staring any particular event in the teeth?

Childs: It depends on whether you mean a cataclysm for humans or a cataclysm for everything else. The cataclysm for everything else is happening already. We’ve fragmented habitats to the point that extinctions are rampant. In making our civilization stronger, we’re killing almost everything around us.

But there are also countless cataclysms with our name on them, ready to roll. The fragility of our agricultural system comes to mind. Overpopulation. Sea-level rise. For other species sea-level rise is just cosmetic. A marsh goes underwater; another marsh develops. Humans, on the other hand, hang tight to the coastlines. We’re an amazingly adaptable species, but we’re slow-moving in response to climate change. We’ll be the ones to feel it sharply.

Droughts are also a possibility. I’m not talking about the sort of droughts we’re experiencing now. We’ve enjoyed two thousand years of almost drought-free living. What we call “droughts” are really just a little aridity, a dry patch in time. If you look at the last ten thousand years, you see droughts that sank us into periods of extinction, droughts that lasted a thousand years or longer.

We look at the earth as a constant, not realizing how easily it can change. We often make our calculations as if the carbon dioxide and other pollutants we are adding to the atmosphere were the only climate variable, but that isn’t the case. A year of heavy volcanic activity would cloud the atmosphere, blocking sunlight and dropping the global temperature enough to devastate agriculture. There are many moving parts.

Tonino: How frequently does the earth experience a year of heavy eruptions?

Childs: Every two to three hundred years. We haven’t had one since 1816, which is known as the Year without a Summer. Earth had barely a billion people back then. Now we have more than 7 billion. If we had a year without a summer today, we’d see a collapse.

It’s important to understand the time scales at which these events occur. Basically there are episodes that happen every few hundred years, episodes that happen thousands of years apart, and episodes that come around only a handful of times in the entire history of the planet. You may have heard that the super volcano under Yellowstone National Park is overdue to erupt, so you’d better build your bunker now. But its last big eruption was 640,000 years ago. If it stays on schedule, it could erupt sometime in the next forty thousand years. So there might be more important tasks to devote your time to than bunker-building. If Yellowstone blows, your bunker’s not going to help anyway.

The end is always happening. We think of apocalypse as a moment — a flash of light, then you’re gone — but if we study the earth’s history, we find that it’s not one moment. It’s actually a long process. In fact, it’s hard to see where it begins or ends.

Tonino: Are human civilizations subject to the same laws of flux and metamorphosis as the planet?

Childs: I believe so. I’ve looked through a lot of ruins. You see the story of human civilization flourishing in a particular place, then coming apart, and the survivors moving to some other place or adapting where they are. Individual communities fall, but civilization on the whole has never actually fallen. You could argue that, for the past six to ten thousand years, we’ve been passing the baton from one group to the next. Rome never fell. The Mayan civilization never fell. They just changed. While some cities were burning, others were being built. Civilizations, at least on a smaller scale, come and go. That’s not to say there isn’t misery and death with each departure. But if you step back and look at the ruins, the eroded walls and roads, you confront the plain fact of the rise and fall. It’s happening right now. How many neighborhoods are empty in the Midwest? How many places in Baltimore or Detroit are falling to pieces? Cities are like trees that start as seedlings reaching for the sun and eventually come crashing down in their old age.

Like bees, we’re always building our hives, abandoning our hives, and building new ones. We’re on a different scale and use different tools than bees, but we’re still obeying the same laws. We’re still eating and sleeping and building and procreating. We’re still doing what our bodies tell us to do.

Tonino: What are the main factors leading to the collapse of a civilization?

Childs: The big one is infrastructure decay, which is generally preceded by conflict and resource depletion. Look at the Hohokam, a pre-Columbian people who lived in what is now Phoenix, Arizona. The Hohokam started their civilization around 300 BC and pulled out of there about 1450 AD. That’s a long run by our standards. During that time they had seven hundred to a thousand years of high productivity, building pueblos and burial mounds and ball courts and hundreds of miles of canals in the Phoenix basin. It was an impressive spread.

Studying the decline of the Hohokam, we see shifts in response to environmental pressures: People flee conflict and drought. Malnutrition begins to be a problem. Then the canals start to fail, and nobody repairs them. Then a flood hits. When floods have hit the Phoenix basin before, filling the canals with silt, the Hohokam have always cleaned them out and repaired the damage. But nobody is repairing the canals anymore, and only a few are working. The whole system has decayed. And, pretty quickly, everybody disappears.

I think failure to address damaged infrastructure is a key indicator that you’re about to lose a particular civilization. Studying the Mayan site of Tikal or Angkor Wat in Cambodia, you can see the same pattern: First the water system breaks down. For a while the people adjust, bringing in water via different means, building in new places. But when people stop building, stop fixing problems, the end is near. The culture loses its flexibility and becomes brittle.

Tonino: Looking at this country today, what do you see? Are we ascending, on a plateau, or spiraling downward?

Childs: This goes back to the idea of everending: as one thing is ascending, something else is falling away. If you were a Hohokam, would you have been able to tell when your civilization began to fall or what chapter of the story you were in? Eventually there’s a moment when you know for sure it’s over: the villages are abandoned; people are dying. But even then it might be tough to tell whether it’s really the end.

Infrastructure failure is rampant right now, especially on the East Coast, where everything is older. The pipes that were put in to last a hundred years are a hundred years old. The bridges that were built to last fifty years are fifty years old. I don’t want to make it sound like we’re doomed, because repairs are being made, but failures are also increasing — bridges, water mains. When you see that happening, it’s time to sit up and pay attention.

Tonino: You’ve written that a proper measure of a civilization should be not how well it stands but how well it falls.

Childs: You can fall in chaos and destruction — mile-high flames and people screaming — or you can have a strong-enough infrastructure, a strong-enough culture, that you aren’t destroyed by the collapse. The process plays out over decades or centuries. It’s not sudden. There’s time to change course. Small changes can become big changes. I don’t believe in points of no return. You’re never going to return anyway. It’s always forward.

The fall of a civilization doesn’t have to be cataclysmic. It can actually be generative. It can be the birth of a new civilization. You can fall without even noticing that you’re falling. On the other hand, if you aren’t resilient — if you don’t have the cultural equivalent of biodiversity — then the collapse is going to happen fast. It’s going to be brutal and catastrophic: violent revolution, death, and suffering.

Tonino: But either way, we will fall.

Childs: Yes. How long will the U.S. last? We don’t know. The Chinese city of Chengdu has had the same name for more than two thousand years. Maybe Manhattan will last two thousand years, maybe less. Eventually, though, it will disappear.

This house we’re sitting in could last a hundred years — maybe a couple of hundred if the roof is well maintained — but then something will happen, and this house will be gone. Every house, every city, exists on top of geology, and geology is not stable. We’re right on the edge of a canyon that’s always eroding, opening wider, creeping toward this house. One day that canyon’s edge will be over here, where we sit. It’s inevitable. The end will come. There may be other cities. There may be other nations. But this world we have now won’t last. In many ways that’s a beautiful notion to me.

Tonino: Why?

Childs: It just pleases me to understand that everything has that long history of rising and falling built into it. It’s exciting: There’s geology here! There’s a pattern of ancient winds in these rocks! What does that mean? Where does that put me? How do I relate to ancient winds? Does this mean that the winds I’m experiencing now will someday be ancient? That I will be ancient? Then I get it: My now is not the only now. There are many nows.

When we recognize that we’re not alone in time, we can understand our impacts and our decisions in a greater context. We can see how we change the world, and how the world changes. It’s not a feeling of insignificance. It’s like being a player in a game where your choices matter.

But then sometimes there is a curious feeling of insignificance. For a few seasons in Colorado I worked on a Pleistocene excavation. We were digging down 2 million years, looking at bones and remnants from the Ice Age. I asked a geologist digging next to me, “Do you think our civilization will be visible in layers like this 60 million years from now?” He said no. Future scientists will see evidence in the fossil record of species disappearing. But as far as our civilization goes, he said, we’re going to be invisible.

We like to think that what we’ve made will last forever, but take a closer look. Metal? That’s not going to last. Plastic? Not a chance. A plastic bottle will be around for five hundred to a thousand years before it breaks down. But ten thousand years, a hundred thousand, a million? No way. The evidence will be gone.

There’s a pretty good chance that humans won’t show up in the fossil record at all. A Coke bottle will look like what? Some kind of fossilized worm burrow? In the fossil record it will be apparent that mammals had a good run, but not every species will be represented. We are mixed in with almost 9 million other species on earth. Which ones become fossils is pure chance. And civilization has been around for only six, or maybe ten thousand years. That’s an onionskin in the geologic record, the thinnest slice of time. A narrow layer of dark rock may be all that remains to suggest we existed.

When that geologist told me this, I found it heartening. But when I wrote about the experience, many readers thought it was depressing. They didn’t love knowing that we’re part of a much larger story. I understand that: You’ve got to survive. You’ve got to fight for your own existence. Every day is work. Why would you want to accept the mortality of your civilization? But we’re talking about the energy that drives everything. If there weren’t a dynamic that took things apart, this whole world would be in stasis. Nothing would change or be created.

Destruction and creation can’t be separated. The fact that they both exist means that the ball is rolling, the planet is moving forward.

We are mixed in with almost 9 million other species on earth. Which ones become fossils is pure chance. And civilization has been around for only six, or maybe ten thousand years. That’s an onionskin in the geologic record, the thinnest slice of time. A narrow layer of dark rock may be all that remains to suggest we existed.

Tonino: Can an analogy be made to the minor disasters we face every day, each of us getting knocked about by life?

Childs: I write in Apocalyptic Planet about visiting a relative in Southern California who was going through a treacherous divorce. There were wildfires burning in the hills above her house, and ants and rats had invaded it. Her refrigerator was broken. She was a wreck. Her life was coming undone around her.

We face the collapse of our lives again and again. It happens on Monday, on Tuesday, on Wednesday. Though I sometimes write about the geologic view, the big picture, I also believe in the significance of daily life. Sleeping, waking up, and figuring out what to do next is what drives all the changes. We live in two worlds, the big and the small, and both deserve our attention.

Tonino: You mentioned to me in an e-mail that your life has been chaotic of late, but you also joked that it’s been chaotic ever since you were born.

Childs: It’s always a mess. I lived out of a truck for years in the desert. I wrote using the tailgate as a desk. My truck looked like a human-sized pack rat lived in it. There’s a lot of messiness around me here, too — stacks of papers and books. Right now I’m in the middle of a divorce. Another mess. Another force of chaos. But when isn’t something big happening? I go into the wilderness, look at a dangerous situation where I could die, and then I step into the thick of it and find my way.

Is my life being destroyed right now, or is it being created? I’ve got two kids and the book I’m writing now and the next one after that. It’s feast and famine at the same time.

Tonino: It reminds me of what Charles Bowden wrote about Juárez, Mexico, and the violence and poverty overwhelming that city: “I can’t decide if I’m hearing the cries of a hard birth, or something more like a death rattle.”

Childs: We’re always hearing both.

Tonino: You mentioned danger. Is it important to your work? Are you, in a sense, trying to come closer to those larger earthly forces by taking risks?

Childs: I’ve asked that of myself a lot, because I do put myself in danger. I don’t necessarily go looking for it, but I find it, or it finds me. I’m a father, so it weighs on my mind.

There is something about a moment of danger that is clarifying: unless you can find a way out of this tight spot, it’s all over. I remember being on a river in Tibet that no one had ever run, and our group was in the middle of a five-mile-long rapid at the bottom of a three-thousand-foot-deep gorge. For a moment I couldn’t tell upstream from downstream. It was just walls of water everywhere. I thought about my two boys and knew that I would chew my way through the planet to get back to them if I had to. The imperative to find my way home was the only thing on my mind.

I seek an elemental existence in which everything else has been stripped away. Danger is a cheap, fast means of getting there. On that rapid in Tibet there was nothing but the crystalline moment. There was only water and gravity and the thought of my two boys. In the rest of my life I’m wondering what I’m going to have for dinner, and did I make that call I was supposed to make, and how much gas is in the tank. Those concerns distract us, but the clarifying moment brings us back.

Tonino: You’ve said that the word wilderness is too simple for the terrains that you explore.

Childs: It’s one of those words that could mean many things. My definition of wilderness is not restricted to designated pieces of land. It’s any place where we venture into the unknown, especially outside of the civilized realm. For me as a kid, wilderness was a culvert with a thin dribble of green water flowing through it. It was abandoned houses and cellars filled with weeds. It was stepping out of my everyday world. Is a culvert on the edge of the schoolyard a wilderness? Not exactly. But it was somewhere I could escape the control of human society and be controlled by the elements themselves. Yes, the culvert was a product of civilization, but it was also more. It was the ribbed aluminum pipe and the trickling water and the slime and the drips and gurgles and echoes. It was what I became when I was immersed in that place.

I am fortunate to have spent long periods in remote landscapes as an adult. Few have that privilege. But you don’t have to travel a thousand miles to experience wilderness. There’s always a creek nearby, a place behind a fence where nobody goes, a tree root pushing up through the sidewalk. Sometimes it’s just a bench where you sit and look at something beyond yourself. Dawn is a wilderness.

Tonino: So it’s a quality of being.

Childs: Yes, it’s how you are when you’re there. It’s what you become when you let the place saturate you. I’m talking about the way your heart changes. It becomes inseparable from the place.

Tonino: But the specifics of a place do matter. Every place is nuanced, right?

Childs: Oh, yes, the specifics are everything. I’m personally drawn to desolate landscapes because they pull me in so quickly. I walk barefoot across this four-thousand-square-mile field of dunes in the Mexican desert, and I inevitably forget who I was before the trip began. I wonder: Where am I? Who am I? What am I? I lose my boundaries and take on the qualities of the landscape around me. I’m no longer an individual; I’m the place, whether that’s a culvert in the suburbs or four thousand square miles of shifting sand.

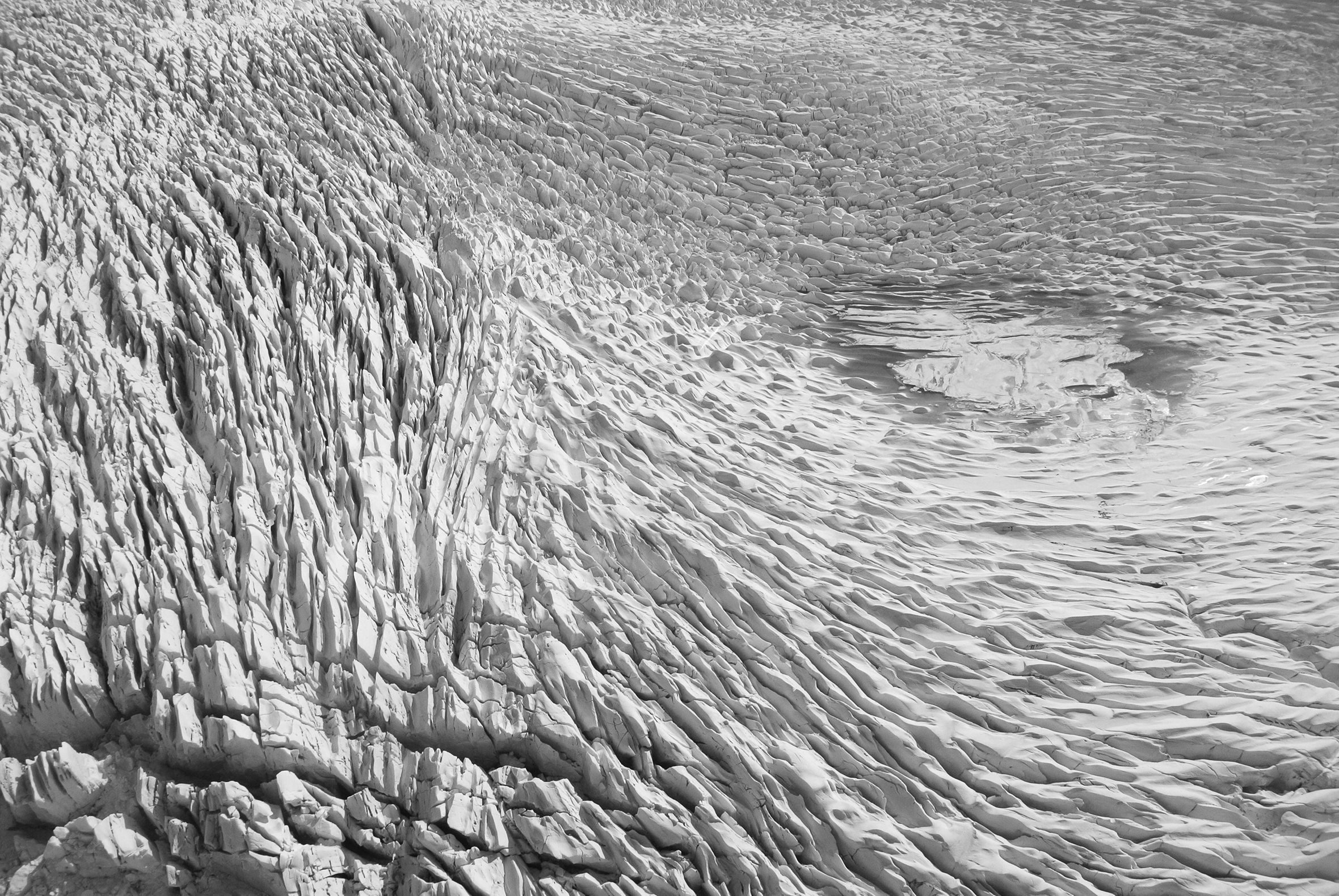

I do achieve this most consistently in exposed, naked landscapes: Ice landscapes. Rock landscapes. Arid landscapes. Landscapes where there are no trails or destinations; where there are few life-forms and the bones of the planet are laid bare in front of you. It’s all so clear there, so clean. Maybe you find broken pieces of pottery, or you sit down where somebody sat ten thousand years ago and sharpened a stone, and the flakes are still there.

I often go backpacking in the canyonlands of southern Utah. In that place you’re constantly touching rock: you’re climbing; you’re picking up rocks and running your fingers over them. Maybe three weeks into one of my trips I noticed that my fingerprints were gone. I had worn my fingertips smooth from so much contact with abrasive sandstone. It felt liberating. I had no identity. My identity was the place. I thought: I’m finally here. I’ve been let in through a back door to a world of canyons and buttes and a nameless body on the move. When my fingerprints grew back, I was disappointed to realize that I couldn’t get rid of myself so easily.

I love living landscapes, too: uncurling ferns and water dripping and mammals lowering their heads for a drink. But I want to see what’s underneath all that. What is the fundamental nature that’s left behind when you take that away? A few years ago in Hawaii I walked through a fresh lava field that had just poured over a subdivision and patches of rain forest. The ground was still as hot as a wood stove. I camped in cooler patches among the fluid shapes: so elegant, so basic. It was like traveling back to the start of creation. Here was the raw matter that became life.

In a place like that, you get down to what has always been here and what will persist after the subdivisions and the rain forests are gone. Desolate landscapes remind me that there are stories that go beyond life, that underlie everything. When you consider that plants and animals somehow emerged from this primal material, you can’t help but see life inside the nonliving. There are places that are special to a person, to a culture, to a civilization, but the whole damn planet is sacred. It is all alive and interactive. There are no impermeable boundaries. Sacredness is creation. It’s where life rises and falls and rises again. Where isn’t this happening?

Tonino: As the father of two boys, how do you find the time for protracted trips into the wilderness?

Childs: Either I take them with me, or we endure the separation. Before kids, I was gone all the time. Now I can’t be away from them for long; my heart aches too much. It’s best when we are out there together.

When I go backpacking with my twelve-year-old, his rules are: No tent, no stove, no map, no trail. We just eyeball it. The shape of the land determines our journey. We go out for five days, and every step is a decision. We are led along by geology. The land influences where we eat, where we sleep, the shapes our bodies take: Are we curled up in a ball for shelter, or stretched out to reach the next handhold when we’re climbing? Sometimes we come upon a mountain lion’s tracks and follow them, reading the story they tell. You can see the moment when the lion paused and looked around. And now you’re pausing, shifting your weight, leaving your own track.

Tonino: Do you think the same goes for our inner lives? Are our thoughts and moods and dreams shaped by the land as well?

Childs: Yes. When it rains, you’re one person. When the sun comes out, you’re another. We’re especially receptive to the human history embedded in a place. The history in the ground radiates all around us.

Recently my wife and I went backpacking in a remote canyon around the Four Corners to find this eight-hundred-year-old seed jar that I had discovered on a trip we’d taken together years before. The jar was from a period when drought had struck and massacres were occurring. People were on the move, exiting the region, looking for the next place. The seed jar had probably been stashed for safekeeping. The public-radio program and podcast Radiolab asked if we could find it again, and they sent us out with a producer. Just to spoil it for you, we found that a rock slide had destroyed the site. When we got back to camp, my wife told me that she felt like that jar: something had been destroyed, and our marriage didn’t make it long past that.

We’d gone looking for an artifact from the end of a civilization, and it turned out to be the end of our marriage. It felt as if the history of the place were rubbing off on us. We weren’t independent of it. We were a part of it.

Tonino: It seems as if many of us today are isolated from the outside world. Do you think that places seep into all of us, regardless of our sequestered lives?

Childs: I have met very few people who don’t believe in the importance of place. Maybe I’ve got a skewed sample of backpackers and nature writers, but I find that almost everyone talks about their home landscape. Mine is from southern Arizona to the Rockies. I haven’t made my home outside of that zone.

A house can be as much a place as any. It has a context. It has a city around it, and the city is held by the land. Phoenix is an endless sprawl of asphalt and strip malls, but its saving grace is the mountains that stand up from the middle of it in Papago Park. That topography is home for people from Phoenix, whether they’ve ever set foot in the park or not.

I feel like everybody has a connection, one way or another, to the shape of the sky, the line of the horizon. Even as technology distances us from the land, we maintain a relationship to it. It’s not a choice. Something keeps us attached.

We’re even connected to landscapes we’ve never seen in person. For example, we have a genetic affinity for savannas. We prefer the shape and feel of them. Our ancient ancestors came from places like those, and our bodies remember them. This tells me that, even when we’re living inside a box, we’re also living beyond the box.

Honking horns and computer screens and long lines in airplane terminals can make us sick, but the stress of living near saber-toothed cats on the prowl was probably sickening, too. Maybe balancing on that edge between sickness and health is what it means to be alive.

Tonino: Paul Shepard argues in his book Nature and Madness that our modern way of life goes against the grain of who we really are as a species, and as a result it makes us sick. Do you agree?

Childs: Yes and no. I get sick of civilization. It can be draining. When I’m in Manhattan, I see the beauty in that city — I even like it there — but it doesn’t take long for me to worry that I’m going insane. I can’t find any quiet. But we’re adaptable as a species. Honking horns and computer screens and long lines in airplane terminals can make us sick, but the stress of living near saber-toothed cats on the prowl was probably sickening, too. Maybe balancing on that edge between sickness and health is what it means to be alive.

In my life and in my writing I try to accept that we’re tumbling headlong into a new type of existence but also to remember what got us here. Don’t forget what it’s like to be an animal on the land. Don’t forget what it’s like to look a large predator in the eye. Don’t forget the simple skills.

I’ve met people who say they can’t sleep on the ground and ask me how I do it, as if it were some kind of trick or talent. I say, “Well, you get on the ground, and then you sleep.” Their confusion is both funny and disconcerting. We evolved to sleep on the ground. Our spines can be fitted to the earth’s contours like a puzzle piece. We shouldn’t lose that. Sleep in beds, but don’t forget the ground. Civilization separates us from these older experiences. Maybe it’s not civilization itself that’s maddening; it’s the way it detaches us from the past that can drive us insane.

Tonino: Don’t ancient human tendencies keep popping up over the ages in different guises? Maybe posting on Facebook is a manifestation of the desire to share stories around the fire.

Childs: Oh, yes, it’s the same impulse. I was out on an ice field a couple of years ago in Alaska, and we carried a satellite phone with us. One of the team members had a dying mother, so he was calling home. Initially I was irritated by the phone’s beeping. I kept thinking that we weren’t quite present. We were on an ice field in Alaska, and he was talking to somebody on the East Coast. What did that mean for us? Where were we really?

But then I thought of how the native peoples of the Arctic have been making rock stacks called inuksuit for centuries to convey messages: to say that something happened here, or that you should go left or right. It’s a way of communicating beyond the range of your voice. So is a satellite phone. Sending signals is something we’ve always done.

Everything we do is an extension of ancient activities. Driving is just a faster way of walking. But these new versions of old ideas are also not the same. When you’re driving, you’re making decisions about passing or turning, just as you do when you’re walking, but you’re interacting with the landscape in a different way. When you’re walking off the trail, every step is a question: Should I go left or right? Up or down? Behind that tree or in front of it? That’s something I think we’re losing. We are tactile creatures, built to take in the landscape and process it. We aren’t asking the landscape questions anymore. The world we’re interacting with is mostly human made. We’re asking questions at the office. We’re playing games on the computer. It’s still stimulating, but in a different way.

Tonino: What about the animals you encounter on the land? How do you interact with them?

Childs: I admire their life in the world. I admire how they move with such elegance, such knowledge of their bodies, such awareness of their habitat’s features. I know some incredible rock climbers who move the same way. They have a cat’s instincts. They can bound. They can conserve their energy and then burst up the face of a cliff.

I hesitate to use the word pure when describing how wild animals move, because I think we move through the world with our own purity, but with animals it’s just so physical, so precise. I miss that in my own body. I miss participating in that wildness.

In certain moments with animals, when you’re making contact, you’re talking without words. I remember coming across a cave in the high desert during a snowstorm. It was a small cave, maybe knee-high. I crawled into it, because that’s what I do when I find a small cave in the desert. As I stuck my head in, I saw a face right in front of mine, but I couldn’t quite make it out. It took me a second to realize there was a black bear six inches from my nose. I’d awakened it out of hibernation. In that moment I could tell exactly what the bear was thinking: Make this guy go away.

I know we hesitate to anthropomorphize, but what other choice is there? To conclude that bears don’t feel? That they don’t respond? Obviously they do. In such a moment you’re having a conversation. You’re entering the time described in the old stories, when all the animals spoke a shared language.

Tonino: What old stories are you thinking of?

Childs: Aesop’s Fables or Native American tales about Coyote and Raven. In those stories humans and animals are always chatting away. I think it still happens. It doesn’t have to be as extreme as an encounter with a bear. It happens with house pets. You’re sitting on the couch, and the cat looks at you: Hey, person. You nod: Hey, cat. Animals will always draw us into conversation.

Tonino: The main theme in your work seems to be transformation — how the land changes, and how it changes us. It’s as if the land were a portal that we pass through.

Childs: I’m kind of a transformation junkie: I want to go out and be changed. Like you said, the land is a portal. But it’s an interesting kind of portal: It’s a place that takes you to itself. You pass through and arrive right where you started, but something has changed.

Moments like that one with the bear, when I’m suddenly facing another animal, have changed me. Once, a mountain lion came up to me and stopped four feet away. I pulled out a knife and got ready for it to attack. I look back on my reaction and think: Damn, that was so human of me to label the moment as “violent,” as if it weren’t big enough to hold more than one label. What if the mountain lion was just curious? What if I hadn’t taken the knife out? What if the lion and I had said hello? What if we’d had a conversation?

After the lion left, I felt as if I’d just traveled a million miles at light speed. I remember looking at my hands to make sure I was still me. Something had changed, but what?

At that time in my life I wore a claw necklace under my shirt and a raven necklace up around my throat. The raven was kind of my totem animal, the one I related to the most. Later that evening I reached up to touch my raven pendant, and it was gone. It had fallen off. So I tightened the claw necklace up around my neck, replacing the raven, and I wondered: What just happened? Did I go from the raven side to the mountain-lion side?

Tonino: Why was the raven your totem animal?

Childs: Ravens and I often make eye contact. We talk. I call to them. They call back. We puzzle over each other.

It’s not just ravens, not just these classic totem animals. I’ve had associations with deer mice. The way they are in the world tells me something about the way I am, or the way I could be. I pad along like a mouse. I hide and shiver. I come out at night and traipse about. And the mountain lion teaches me about silence and power. I believe we all have lessons to learn from animals.

Tonino: I see similarities between your descriptions of wilderness experiences and other people’s descriptions of drug experiences. Is the earth itself the ultimate drug, a doorway to a new state of consciousness?

Childs: Yes, and it’s an easy doorway to find, because it’s everywhere. Walk down the street and watch the leaves blowing past — just stand there and watch them roll along and let them take you out of yourself, out of your moment, and into something much bigger and more powerful. There’s no way it won’t spin your brain.

Once, in those dunes down in Mexico, I saw two milkweed seeds — tiny spheres trailing fine filaments — just dancing across the sand in a light breeze. I followed them. They would part ways, separating by a hundred feet, and I would think: There they go, off on their individual journeys, never to meet again. But then they would dance back together, bump into each other, and wander off as a pair.

Another time I was hunkered in the lee of a dune, taking shelter from a strong wind, and a sunflower petal came over the crest, rolled around in the lee, and took off. Then came another, and a couple more. I got up, looked over the crest, and saw a line of flower petals extending out toward the horizon, blowing across the sand. All the petals came through, then the dried pistils and stamens, then some stems and leaves. This flower was stretched out over more than a hundred yards, just following itself across the desert.

That encounter with the sunflower — that’s the sort of trip I’m after. When I load my pack, point myself in a direction, and take off, that’s how I administer the drug. I’ve probably floated down the Green River in Utah forty-plus times, but every time I start out, I’m rubbing my hands together in anticipation. It’s impossible for me to come back unchanged from a week or a month outside. Change is guaranteed.

Tonino: Time is always running faster and slower in your work: it flies by, then creeps along, then flies by again. What does sustained immersion in the wilderness do to our sense of time?

Childs: After seven, eight, nine days in the desert, your sense of time totally changes. In fact, it becomes almost impossible to construct a chronological narrative.

On one trip I was walking at night, dressed warmly because it was cold. The moon was out, and the sand was glittering. Looking back at my journal, I find descriptions of the starry sky beneath me — and I can tell that I didn’t mean it metaphorically. I was actually seeing the sky stretching out under my feet. It makes me laugh now.

So I was looking at the sparkling stars in the sand, wandering along, and I remember squinting and thinking, My God, it’s bright. And I lifted my head to see that the sun was out. It was the middle of the day. I’d just lost nine full hours. Where the hell had they gone? I saw that I had taken off all my warm layers and organized them in my pack. I had to concentrate to reassemble the chronology, to remember the sunrise and how I’d stripped down and packed everything up.

Your perception changes, too. In a place where there’s nothing on which to train your gaze, your focus is distributed across the entire horizon. Your peripheral vision becomes enhanced. You can see shooting stars — not just at night but also during the day. After a while you realize everyone with you is having the same experience. You talk about it at camp: “I keep seeing these streaks of light.” “Yeah, I’m seeing them, too.”

Out there you’re just moving through sand. It’s flowing and blowing all around you. You have to cut holes in your pockets so the grains will drain out. You lose all sense of here and now versus back there, back then. You are beyond time. Time abandons you. Normally our brains are dividing everything up into pieces, but if you’re out in this peripheral landscape where there’s nothing for your brain to divide anymore — just dune after dune, seamlessly woven together — time becomes equally seamless.

Tonino: You’ve taken long walks across military ranges where bombs, perhaps the premier symbol of humankind’s capacity for violence, have been detonated. What are those places like?

Childs: I don’t do that as much anymore — getting older, having kids — but I used to go into the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range in the deep desert of southern Arizona. I’d just park my truck, throw a camouflaged tarp over it, and take off walking. At night I could see where the troop movements were, and I would head in the opposite direction. I’d walk for weeks, completely alone.

I was on a range in New Mexico not long ago, looking at woolly-mammoth tracks as research for a book. The tracks are about twenty thousand years old, and they were right there in the sediment. Shrapnel and old, eroded bomb craters were all over the place. Just over the horizon was the Trinity Site, where the first nuclear bomb had exploded in 1945. To be out amid craters and shrapnel and twenty-thousand-year-old mammoth tracks was another example of time becoming thin.

I’d come there to study the Clovis people, who were mammoth hunters, and the weapons they made — spear tips we call Clovis points. A military friend who was with me was talking about defusing bombs in Iraq and Afghanistan. I was thinking about the nuclear bomb, and about the Clovis points. It felt as if time was all one moment: You look down, and it’s twenty thousand years ago. You look up at the horizon, and it’s 1945, and the bomb is exploding.

Maybe chains of influence ripple forward and backward through time. Maybe the Clovis camped there to craft their weapons because that’s the place where we would one day choose to detonate the bomb. And if time is that thin, does that mean space is equally thin? Looking down at the twenty-thousand-year-old mammoth tracks, am I also standing in all the other landscapes of my life?

I’m so damn lucky, so fortunate to be granted these kinds of experiences. There’s a different world hidden inside this one. There is the world in front of us — the one we move through every day, going to work, paying taxes, and so on — and inside of that are centuries, thousands of years, millions. There is not just a single “now.” I believe we all have access to that insight, but so much depends on the place, the circumstance.

Tonino: I can imagine a person hearing that and saying, “That’s great, but personally I couldn’t care less about what happened thousands of years ago.”

Childs: I hear that voice, too. I’ve spent a lot of my life picking through ruins, looking at rocks, observing the paths of ancient winds, and I don’t know if it’s done me any good. It’s resulted in stories and books, but I don’t know if it’s made me a better person. I sometimes wonder if such experiences benefit us; if they help us get through our daily apocalypse.

What compels me, I think, is the need to tell stories. I come out of the backcountry thinking, Oh, my God, I just saw the stars glittering beneath my feet and a mountain lion right in front of my face. I’ve got to tell somebody about this! It feels important to add my testimony to the chorus of voices. But I’m not trying to save you or save civilization or save the world. The world doesn’t need saving.

Tonino: What about conservation, though? Isn’t it important to work on behalf of the endangered parts of the world?

Childs: Yes, of course conservation is important. I feel indebted to people who are working hard on it: firing off lawsuits; standing up for specific places, specific animals. I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing without them. I wouldn’t have access to these landscapes. So much would have been destroyed.

There’s a Hawaiian word, kipuka: it’s a place where lava flows around a piece of forest, leaving a little island of green in a black lava field. In a landscape that is suddenly all rock, the kipuka serves as the genetic bank. Whatever grows back will come from this one source. I look at the kipuka and think: That’s the way to protect biodiversity on this planet. Create as many kipukas as you can. Preserve as many different ecosystems, as many different cultures and languages.

A kipuka can be as high-tech as the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway or as simple as your backyard. Writing Apocalyptic Planet, I talked to a woman in her eighties who cares for a half acre of virgin prairie in Iowa. Surrounded by industrial cornfields, she was out there with her walker tending to a plot that had never been plowed. Maybe in the bigger picture that’s a drop in the bucket, but after you’ve seen those cornfields, those monoculture crops everywhere, a small plot of native plants is everything.

I’m amazed by the good we can do. We’re not just a devouring species, eating everything in our path. We’re also a species that preserves ecosystems, that cleans up rivers, that puts seeds in the ground. We aren’t just destroyers. We are repairers, too. Destruction and creation — it’s always both at once.