Jane and I were in my room having one of our sleepovers, doing the things we always did together, like shining flashlights under our chins in front of a mirror, or holding our eyes open as long as we could without blinking. Tomorrow my mother would take us to Rose’s, our favorite department store. At thirteen, I could think of nothing more fun than going to Rose’s with Jane. My mother keenly understood this, which was one of the reasons I loved her so much, one of the reasons I could not bear the thought of her death.

At Rose’s you could always find the latest fad items, like troll dolls, Jesus Christ Superstar buttons, plastic Buddhas, and rabbits’ feet. Jane wanted a rabbit’s foot: she had held mine in her hand all day, ever since finding it among my precious trinkets. She’d held it so much it was damp from her sweaty hand.

Tomorrow we would spend the afternoon at Rose’s, but tonight we were staring into the mirror, our flashlights transforming our faces into those of hideous crones, reinforcing how awful it would be to get old. We had accepted that we were ugly compared to other girls, but to be old on top of that would be too much. We would never get old, we decided. The thought of looking like that, distorted and wrinkled beyond any semblance of our former selves, was the worst thing we could imagine. I told Jane that I never wanted to get old, not ever; that I hoped I would die before I turned fifty. Holding the rabbit’s foot tightly, Jane said she wanted to die before she turned fifty, too, and I took the foot in my hand and wished on it, then gave it back to her.

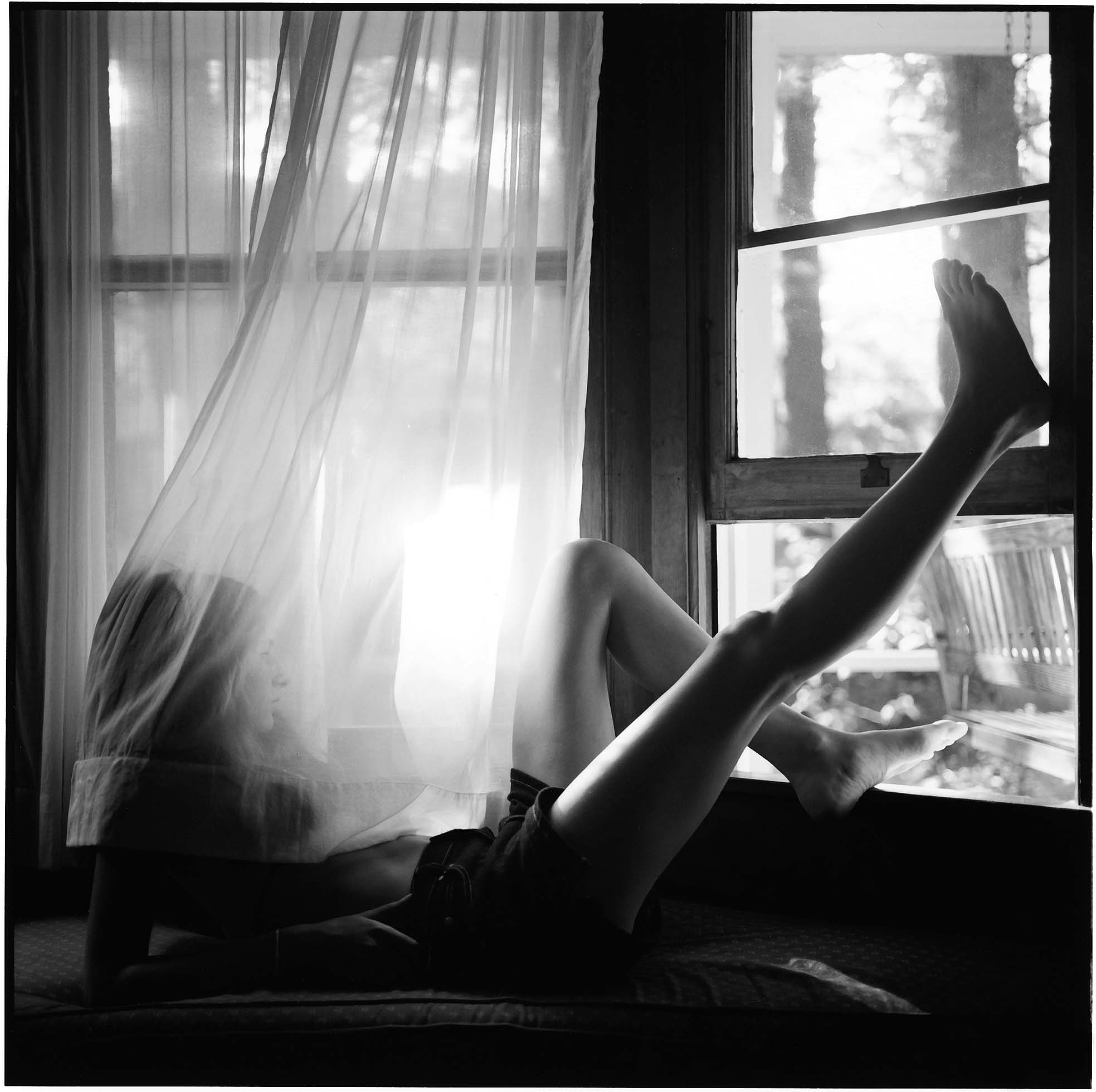

Next we lay on my bed and propped our butts up with our hands and stuck our skinny, hairy legs straight up and pedaled like wild.

“I dare you to call Carl Leach,” Jane said.

Carl Leach was in our accelerated-learning classes at school. He was friends with Steve Roach, and together they had formed a rock band. Carl played drums; Steve played guitar. They were very serious about their music. They dressed in jeans, fringed vests, and leather chokers. “Leach and Roach,” people called them, always “Leach and Roach.” Even the smart kids never called them by their first names. People, I had found, were cruel. I was cruel, too; I just didn’t know it.

I did not see how Carl Leach and Steve Roach could ever think their band would succeed, because although they took their music seriously, no one took them seriously. Their music could never be anything but a joke.

I didn’t care that Carl wasn’t popular, though. I was drawn to his loneliness, believing it resembled my own. His face was pimply, but it had a gentleness that you had to look past the raw red eruptions to see. I thought I was the only one who could see that gentleness, and for that reason I was sure that Carl would someday fall in love with me. He was a beautiful person trapped in the temporary ugliness of that face, and I imagined that manhood would transform him. He would become handsome, and then he would love me and only me, because I had seen his beauty when no one else had. He would thank me for this someday, underneath a starry, starry sky, and we would get married, have children, and be happy. That was one future scenario I imagined for myself.

I did not know much else about Carl, except that his father was a land surveyor and had his own business called Carl Leach & Son Enterprises. I also knew that his mother had been sick for a long time and had recently died. Sometimes I thought about asking Carl what it was like not to have a mother. But I didn’t ask, because I did not think he would give me a real answer. He would probably say something like “Rock-and-roll is my mother now.”

“What would you give me if I called Carl Leach?” I said to Jane, then immediately regretted how I’d worded the question. Jane did not have anything I wanted. Her family was poor and lived in an old wooden house with warped floors way out in the boonies, on a hog farm that smelled like rotten goulash. Jane was ashamed of her house. The first time I went there for a sleepover, we rode her school bus, and every now and then she would point out the window to a deteriorated barn or shack and say, “That’s my house.” And I would say, “That’s not a bad house,” or, “That’s kind of cute.” And Jane would seem relieved, and she would say, “That’s not really my house.”

Jane once told me that she and her grandmother had passed by my house, and Jane had said, “Grandma, that’s my friend Nora Walker’s house.” And her grandmother had said, “Oh my God!” because she thought our house was someplace rich people would live.

Truthfully, our house was not that terrific, just a one-story brick ranch with three bedrooms and a bath and a half. But it had been built at a time when Jacksonville was making the transformation from rural to suburban, and suburban kids thought they were better than rural kids. I told myself I did not think that, but secretly I did. I liked the idea of Jane’s grandmother saying, “Oh my God.” I felt better than Jane because of our house. I’d also felt superior when Jane had eaten a whole box of ice-cream sandwiches out of our freezer because she did not have such treats at her house. I told my father what she’d done, and a look of concern had crossed his face, not for Jane’s economic status, but for my surplus of attitude. I think my father sometimes worried that I was spoiled, though he did not by any means pamper me. My father had worked hard all his life, first in the Marine Corps and then in civil service at Camp Lejeune. He did not make a lot of money, but civil-service jobs paid better than most jobs in Jacksonville.

So I regretted asking Jane what she would give me, but it was too late to take it back.

“What would I give you if you called Carl Leach?” Jane replied. “I’d give you a big, fat lip!”

Her answer surprised me so much that I burst out laughing and pedaled harder at the air. Then I was not just pedaling; I was dancing, and so was Jane. And I knew we would always be best friends.

Jane and I were not allowed to shave our legs. Other girls our age were wearing makeup and bikini panties; we wore no makeup and those big cotton drawers that reached all the way up to our bellybuttons. We were so ashamed of our old-fashioned underwear that we held towels in front of each other in the locker room so nobody else would see.

Although we were not as quick to mature as our classmates, we were slowly changing. We still took showers together at sleepovers, but we no longer giggled or spit water on each other. Instead we bathed seriously and stole furtive glances at each other’s pubic hair.

As part of my Carl Leach future scenario, I imagined Jane would fall in love with Steve Roach, and we would have a double wedding. But in another scenario I would never marry, and I would become a famous writer, like Emily Dickinson, only I would be a novelist, not a poet, and Jane would live with me on my estate and type all my novels for me. I never wanted to be separated from Jane. I loved her, and though she played a subservient role in all my plans, I was afraid of losing her. I feared she would slip away and find a worthier friend, somebody who did not feel like she was better because her house was more expensive than Jane’s.

I was also afraid of losing Jane because I feared I was boring and kind of dumb, even though I was in the accelerated-learning classes at school. I did not feel as smart as my classmates, Jane included. They were all better at math and science, the important subjects that would someday lead to prestigious professions, like doctor or nuclear engineer. I enjoyed English. Nobody thought English was important. What good was English unless you wanted to teach? And everybody, even in the seventh grade, knew there was no money in teaching.

Sometimes when my father and I would get up early in the morning, we would sit on the front steps together and watch the sky fill with light, and I would cry and tell him I did not feel smart. Some old tomcat or another that we kept around would hear us and come threading through our legs. My father would pet the cat lovingly and tell me I had a different kind of intelligence, that was all. I was thirteen, and he no longer took me into his arms as readily as he had when I was small, but I would feel his love in the way he petted the cat, sleeking back its whiskers. At school I felt freakish and disconnected from the world, but my father made me feel grounded and loved.

“Hey, Jane,” I said as we danced our feet in the air, “do you want me to read you a really great story?”

“What kind of story?” Jane said, rolling onto her stomach, breathing hard. She opened her hand, which held my rabbit’s foot, and stroked it with her index finger as if it were a tiny animal.

I reached under my bed and pulled out The Short Stories of Guy de Maupassant, a library book I kept hidden because it both frightened and fascinated me. I was sure my parents would not approve of the stories, but I felt as if they had been written just for me, that no one could appreciate them like I could. I thought I was the only one who could see the rare beauty in them, the way I saw the beauty in Carl Leach. Deciding to share the Maupassant book with Jane was a big step for me.

As I read the story aloud, I pushed away from the world the way you push away from the wall in a swimming pool. I could feel the bed move occasionally when Jane scratched herself, but that was all. I was like a happy child, bobbing in the gay water of the story, which was about a man whose lover died. He missed her so much that he dug her up a couple of days later. Although she had started to rot and stink, he embraced her and took the scent of her death into his “quivering nostrils.”

After I’d finished reading, Jane said, “That’s sick. That’s disgusting.”

“Well, maybe you’re taking it wrong,” I suggested, feeling hurt and disappointed. I remembered what my father had told me about my different kind of intelligence, and I tried to use it against her. “A story is not like a math formula,” I said.

“It isn’t?” Jane said sarcastically. “I thought it was.”

“You have to look at the symbolism,” I said. “Like in The Great Gatsby. How the lights across the water aren’t just lights.”

“I know they’re not just lights, Nora. I get it.”

“I really don’t think you do get it, Jane. I don’t think you understand the story at all.”

“I understand it’s a creepy story.”

“You just don’t understand it,” I repeated, because I did not know what else to say.

Actually, I did not fully understand the story myself. I knew from the book’s introduction that Maupassant was obsessed with death, and that his body and mind were falling apart due to venereal disease. And I knew the story said something important about death. It made me think of the possibility of my mother’s death, putting it at the forefront of my consciousness. Jane’s family’s hog farm had probably taught her about death. Having to kill to survive certainly does that. But I didn’t consider this back then. The hog farm just stank to me, the way Maupassant’s story stank to Jane.

Thinking about it now, I believe what most fascinated me about the story was the stink of death, the way the man in the story willingly breathed it in.

I had been worried about my mother’s health for many weeks. She had just been through a hysterectomy because of “suspicious growths.” I had been so bothered that I could not breathe at night. Sometimes I crawled into my parents’ king-size bed and slept between them, as I had when I was little. I dreamed that a shadowy figure came and sat on my mother, killing her.

Sometimes in the morning my father and I would go for a ride in our old Pontiac, past his childhood home, to the bakery, where we would each get a doughnut. While he drove, he would talk about his mother and his brother, who were both dead. The Indian-head hood ornament on the Pontiac led the way into a future we could not know. Every time my father braked the car, he threw his right arm in front of me to protect me. I wanted it always to be this way.

I put the Maupassant book back under my bed. I was angry at Jane, but at the same time I felt the need to redeem myself.

“Hey, Jane,” I said, “I heard that on that little dirt road down from here there are a bunch of rubbers all over the place. Do you want to go there tomorrow before we go to Rose’s?”

“Really?” Jane said.

In truth I did not know if there were any rubbers down the dirt road or not. I had overheard an older boy on my bus say there were, but he was not very trustworthy. Jane and I had never seen a rubber. Our health teacher had not yet brought one to class. They were a mystery, just like the part of the male body they covered. So far, the best thing to happen in health class had been when the teacher had used a glass Mason jar with toilet paper stretched over the mouth to demonstrate the breaking of a girl’s hymen. She’d poked a Coke bottle through the toilet paper and said, “See?” It was a vivid demonstration — so vivid that in my senior year, when I had sex the first time, I was thinking about the Coke bottle and the jar.

After lunch the next day, while Jane and I were doing the dishes, I said, “Hey, what about that road?”

Jane was already thinking about it. She was doing dishes at lightning speed, plunging drinking glasses in and out of the dishwater to clean them, rather than her usual method: carefully running the floppy sponge into each glass, then wiping the rim with a dishrag.

“What?” Jane said defensively when I looked askance at her methods. “They’re getting clean.”

This was so unlike Jane. She is one of the few people I have known who actually enjoy doing dishes. But she was not concerned about dishes this day.

My mother said sure, we could go for a walk, but we should bundle up because it was cold. And she wanted us back by three o’clock, in time to leave for Rose’s.

Jane and I put on our coats. Jane’s was ratty and pilled from many washings. Mine was white fake fur and brand-new. I had just gotten it for Christmas. I felt elegant in that coat and wanted to wear it everywhere. I rarely had clothes that were the latest style, because my parents did not believe in following fads, but for some reason I had this coat. Wearing it made me feel like I belonged.

About a minute into our walk, Jane showed me that she had put my rabbit’s foot into her coat pocket. “For luck,” she said, raising her eyebrows, like she thought we just might find out what sex was all about.

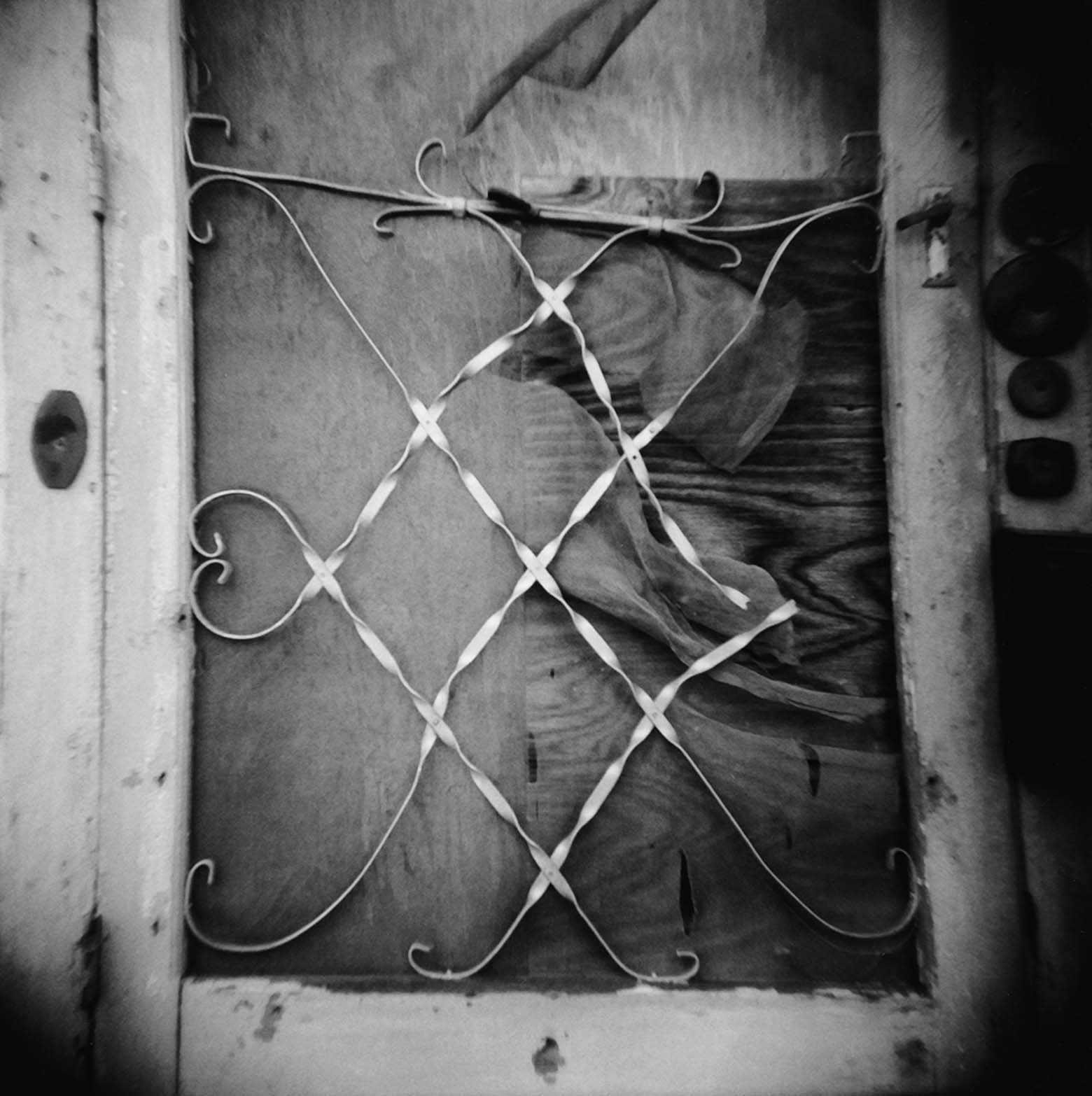

The dirt road was narrow and brushy, not much more than two wheel ruts. We had walked just a little ways down it when we saw a van with Carl Leach & Son Enterprises painted on the side.

“Oh my God, Nora,” Jane said. “Carl is down there.”

“No he’s not,” I said, straining my eyes to see.

“I think I see him. There he is,” Jane said, taunting me.

“Shut up,” I said. “He’s not there.”

I was sweating beneath my beautiful new coat. Just my luck, I thought: Carl down there and me smelling like BO.

But when we got to the van, Carl was not there. It was Mr. Leach and a man he called Gray. A surveyor’s tripod was set up, but they were taking a break. Jane blurted out that we were Carl’s classmates. That’s how it started.

“Come over here, girls,” Mr. Leach said. “There’s a fire.”

His face was homely, and his lips were large and lost their shape when he looked down, the way a camel’s lips do. My stomach lurched because I realized that Carl looked like his father, and therefore would not become handsome. He would never escape the prison of his ugliness. I hated Mr. Leach for destroying the beauty of Carl’s face for me.

It was an unpleasant fire: oily with jagged edges and lots of thick black smoke. But Jane and I walked toward it, because we were cold, and because Mr. Leach had invited us.

“What are you girls doing?” Mr. Leach said.

I waited for Jane to say something, but she didn’t. “Just walking,” I said.

“Walking!” he said, as if it were the most ridiculous thing he had ever heard.

Mr. Leach and Gray smelled like soot, body odor, and whiskey. Sometimes when Mr. Leach spoke, I could see blood on his gums. I tried to imagine Carl and his father together, what sorts of things they might do. Somehow I did not think they sat on the steps at dawn to watch the sun rise.

Mr. Leach pointed and said, “Look out, girls. That’s a crazy man over there.”

A tall man I hadn’t noticed stood on the outskirts of the fire’s warmth. He was not wearing a coat, just a thin, colorful shirt missing most of its buttons, exposing a white, hairless chest. His breastbone and ribs showed. He looked cold.

“If you girls ain’t careful,” Mr. Leach said, “he might rape you.”

At the sound of that word I became aware of my body: how my clothes fit its contours; how one knee sock sagged because the elastic was worn out. I was aware of the place between my legs where beautiful things were supposed to happen, but Mr. Leach was not talking about beautiful things.

“Yeah,” Gray said, “he just might rape you.”

The crazy man seemed young to me. His pants were too short. His boots had zippers on the sides, but he left them open and flapping. Really, I did not think he looked dangerous. More pitiful, like a raggedy clown. He lowered his head and looked at me, then looked off into the trees. I wondered why he had been banished from the fire.

Mr. Leach and Gray suddenly laughed, as if they were still laughing at something that had been said before Jane and I had arrived.

Gray grabbed at his crotch and pulled. “So, like I was telling you,” he said to Mr. Leach, “Me and Skeeter —”

“Skeeter!” Mr. Leach said, as if he were surprised Gray would bring up Skeeter.

Gray said, “Yeah, Skeeter. Like I said, we got them drunk, and Skeeter says he’s got to have him some of that.”

Mr. Leach said, “Girls, get closer to the fire.”

“That fire’s going out,” Gray said.

“You’re right!” Mr. Leach said. “Why don’t we get in the van?”

I did not want to get into the van, and I am sure Jane did not want to either, but we did. Maybe that is how girls get into trouble. It starts out in the most mundane way.

We crawled into the back of the van and sat cross-legged on the dirty floor. Mr. Leach started the engine, turned on the heater, and then got in back with us. We were all in the back of the van: Mr. Leach, Gray, Jane, and me. Before the back doors shut, I saw the crazy man just a few feet away, his chest rising and sinking excitedly. He stepped forward, his boots flapping around his ankles.

“What’s that son of a bitch think he’s gonna do?” Gray said.

“Shit on him,” Mr. Leach said.

“Does he work for you?” I asked.

“Work!” Mr. Leach said. He looked at Gray, like he expected Gray to laugh. But Gray looked suddenly modest, and I thought for a second that everything might be OK. “Yeah, he works for me.”

Gray laughed.

“Oh, he works, I imagine,” Mr. Leach added. “Performs all kinds of works.” They laughed, all traces of humility gone, and I felt scared again. The laughter sounded vindictive. The two men seemed to be laughing separately, not together.

“Ain’t this nice, girls?” Mr. Leach said. I nodded, though I did not think so. Jane’s hands were shoved into her coat pockets. One hand was moving as though she were chasing a small animal around in there, and I remembered the rabbit’s foot. She was fingering it nervously, wishing on it, maybe.

“Ain’t it nicer than the fire?” Mr. Leach said to me. I did not answer, so he asked me, “What does your daddy do?”

“He works on the base,” I said. “He’s in civil service.”

“What does yours do?” Mr. Leach asked Jane.

“Car mechanic,” Jane said.

“Where’s he a mechanic at?” Mr. Leach said.

“Lejeune Ford Sales and Service,” Jane said.

“I hate them,” Mr. Leach said. “Don’t you hate them, Gray? They’re robbers.”

But Gray was eager to get back to his story. “So,” he said, “Skeeter decides he wants him some of that, and he gets her in the back of the van, and he yells to me, ‘She’s got a real nice split.’ ”

Gray and Mr. Leach laughed, as if to say, That Skeeter.

Gray said, “That’s what he said, ‘A nice split.’ ” I could tell Gray wanted Mr. Leach to laugh again, but Mr. Leach withheld his laughter as a show of power over Gray. I had seen boys do this at school. Gray went on: “But then the little bitch got sick and threw up all over him.”

“That’d be it for me,” Mr. Leach said.

“Not Skeeter,” Gray said.

This time Mr. Leach did laugh. They both laughed knowingly about Skeeter.

“He’d better watch out,” Mr. Leach said. “You remember that trouble I had.”

“Yeah, but that wasn’t right,” Gray said.

“Well, she still made trouble,” Mr. Leach said.

“A guy’s always going to have some woman trouble. Right?” Gray said. “Unless he’s a faggot.” Gray shouted this last part in the direction of the crazy man.

Then Mr. Leach and Gray started telling each other jokes, as if Jane and I were not there. The jokes were all questions with lewd answers, like: Why do women have legs? So they won’t leave a slime trail. Why do witches ride brooms? Because the handle fits between their legs.

After they had been telling jokes for a while, something struck the van, three sharp reports, like pine cones hitting the roof. Gray asked what the sound was, but Mr. Leach ignored him and said to me, “I bet you girls already know all these jokes.”

I said I didn’t know those jokes. Just then the van was hit again, several times in rapid succession. The sounds seemed louder inside my head than they could have been in real life.

But Mr. Leach did not want to relinquish his hold on Jane and me. “I’m surprised you girls don’t know those jokes,” he said. “Carl knows those jokes.”

I heard a tinkling, like light gravel hitting the van.

“I would’ve thought Carl would’ve told you those jokes by now,” Mr. Leach said.

Just then something very big and very hard hit the van. I imagined it was a log. The van shook with the impact. Gray popped up like a jack-in-the-box, and Mr. Leach reared up and shouted, “Son of a bitch!” They fumbled with the latches, threw open the doors, and scuttled out on a mission of hurt, though I do not think they found the object of their hunt.

How bright the day looked beyond those doors, so bright it hurt my eyes. How happy I was as I reentered the light.

I think now of myself standing before Gray and Mr. Leach’s fire, before the word came out of Mr. Leach’s mouth that made me feel dirty, like a lower form of life. I think how strong my body was at age thirteen, my ovaries like two ripening strawberries, one of them perhaps at that moment shedding its egg in preparation for my first period. I think how that egg finally traveled through my body and then was reclaimed. I did not know then how beautiful and strong I really was.

When Jane and I got back to my house, my mother noticed grease on my new fake-fur coat. For years afterward, she would not let me forget how she had to have my Christmas coat dry-cleaned when it was less than a month old. This event left her with the lifelong impression that I am irresponsible with my clothes. Sometimes I would like to tell my mother what happened that day — or what almost happened. I would like to tell her, At least the coat came clean.

Jane and I did not speak on the way to Rose’s. Once there, we walked listlessly around the store, which smelled like stale popcorn and cigarettes. We each had a Pepsi, and we fooled around in the Hallmark-cards section.

My mother stood in the hosiery department, holding a package in her hand. “Thigh-highs,” she said. “Do you girls know anything about thigh-highs?”

I knew why my mother was looking at thigh-highs. The incision from her hysterectomy was bothering her, and she wanted to be delivered from girdles and belts. I had heard her talking to my father about it.

“They’re so expensive,” my mother said, hemming and hawing in her usual way. My parents were frugal. They could buy things for me, like a fake-fur coat, because they often did without things they wanted themselves.

“Go ahead,” I said. “They don’t cost that much. Try them on. Then if you like them, you can buy them.”

This seemed to give her permission. “I think I will,” she said, walking off toward the dressing room. She looked small and pitiful, and her hopefulness about the hose put a lump in my throat. I could not stand the thought of somebody putting her in the ground.

My mother returned moments later, looking happy. “They really work,” she said. “They don’t need a garter belt at all. This is great!” She paid for the hose, and we moved on.

We ran across a table with a big sign saying, Everything On This Table — 10 Cents. Jane picked up a rabbit’s foot from the table and said, “I wonder how much this is.”

“It says everything’s ten cents, Jane,” I said impatiently.

“I’m going to buy it,” Jane said.

Though I knew how much she wanted one, I had a sudden urge to keep her from buying the rabbit’s foot. I remembered how she had not understood the Maupassant story I’d shared with her, and the memory grew in my mind as evidence of my superiority over Jane. It became a justification for what I did next.

“What do you want a rabbit’s foot for?” I said.

“For luck,” Jane said, like I should have known this already.

“Jane,” I said, “think about it.”

“Think about what?”

“It’s a foot,” I said.

“I know it’s a foot,” Jane said.

“It’s a rabbit’s foot.”

“So?” Jane said, looking at it.

“See that metal thing the chain’s hooked to?” I said. “That’s to hide the gory part where they chopped the foot off.”

Jane petted the foot, fingered its little claws one by one. “Lots of people have one,” Jane said. “You have one.”

“That’s true,” I said, “but I don’t even like it anymore. Anyway, I don’t care. Get it if you want.”

Jane put the rabbit’s foot down, and my heart soared in triumph. “So,” I said, “you’re not going to get it?”

Jane shook her head.

“Get it, Jane,” I taunted. “It’s only ten cents.”

Jane looked down at the table. I thought I saw her eyes grow shiny and wet.

“What’s the matter?” I said. “Don’t you have ten cents?”

In the parking lot, gravity and the motion of my mother’s legs took their toll. No matter what the package said, the thigh-highs did not stay up by themselves. The stockings kept slipping down her legs, bagging around her knees and ankles. “Girls! Girls!” my mother said helplessly. She began dancing in the parking lot, as though the motion might stop the thigh-highs from falling. She was practically doing the cancan. And she was laughing, like Jane and I laughed when we did silly things. She seemed momentarily young, invulnerable to pain and death. I envied her.

“Nora!” my mother cried in mock desperation. “Help me!”

I wanted to. I wanted to laugh along with my mother. But I could not. I did not. I watched my mother dance in the half-filled parking lot, between cars belonging to people who were also buying things that would not meet their expectations; that would not hold the answers to their problems; that would not bring them good luck.