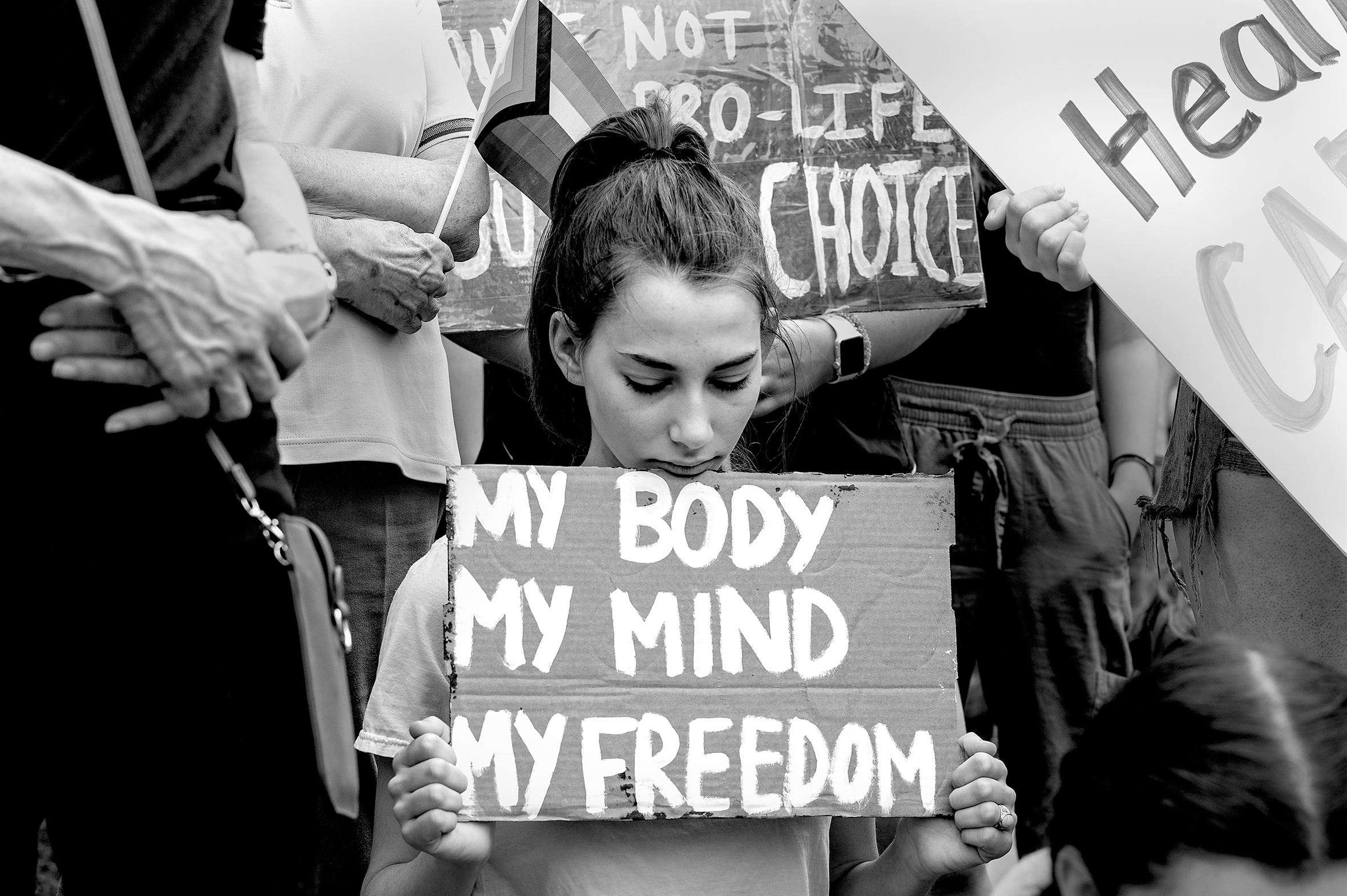

The Supreme Court’s move in June to overturn the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade decision was a seismic one, but not entirely surprising. For decades U.S. states have been restricting access to reproductive rights, and President Trump’s nomination of three conservative justices to the Court had ensured that more states would be free to pass similar laws. But hidden within the undoing of Roe are threats to our rights beyond those pertaining to decisions about our own bodies.

As a legal scholar and anthropologist, Khiara M. Bridges has researched the racial and class aspects of pregnancy and health care, and she sees these attacks on reproductive justice as part of a broader attack on vulnerable people in general. She has been tapped by news outlets to speak about the legal ramifications of Texas’s Senate Bill 8 (S.B. 8), which bans abortion after six weeks of pregnancy and allows private citizens to sue any individual, in any state, who assists a Texas woman in obtaining an abortion, including by paying for the procedure. She was lead author of an amicus brief arguing that Mississippi’s Gestational Age Act, which prohibits nearly all abortions after fifteen weeks of pregnancy, was unconstitutional under existing Supreme Court precedents and that Roe v. Wade should be affirmed. In July, during testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, she engaged in a tense exchange with Republican senator Josh Hawley about his refusal to acknowledge that trans men and nonbinary people are affected by abortion restrictions and regulations — a moment that quickly spread across the Internet.

Her 2011 book, Reproducing Race: An Ethnography of Pregnancy as a Site of Racialization, was the culmination of her doctoral research in anthropology at New York’s Columbia University, where she’d already earned her law degree in 2002. Among other things, she studied pregnant women’s experiences at a public hospital in New York City. Her scholarship explores the relationship between law and culture, particularly “how law constructs this cultural idea of race, and how that idea in turn constructs law.”

Bridges’s interest in the subject of pregnancy was informed by family legacy. Her uncle Dr. James Bridges was a big influence on her — and on the community of Miami, Florida. He was the first Black, board-certified OB/GYN specialist in the state and delivered more than ten thousand babies (one of whom would eventually become one of Khiara’s best friends in college) by the time he retired in 2001.

Bridges, who is also a classically trained ballet dancer, is currently a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley. In conversation she manages to give off an air of approachability that is both genuine and disarming. Speaking with her, I get the sense that she is used to being in front of a classroom and keeping listeners’ attention. She wants us to think more about where culture and law overlap, because the issues that arise there have far-reaching consequences for all of us.

Khiara M. Bridges

Moreno: I want to discuss the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold Texas’s S.B. 8 and its eventual decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization to overturn Roe v. Wade. How did we get to this moment, culturally and politically?

Bridges: We got to this moment because Donald Trump had the opportunity to nominate three conservative justices to the Supreme Court, particularly justices who oppose abortion and oppose any interpretation of the Constitution that protects the right to an abortion. There’s nothing surprising at all about this Court’s decisions. The Right had a long-term strategy of packing the Court and appointing jurists to the federal judiciary who would be willing to overturn Roe v. Wade. This is just the culmination of that decades-long effort.

Moreno: Roe v. Wade protected a right to an abortion up until viability — “capability of meaningful life outside the mother’s womb” — which usually occurs at six months of pregnancy. S.B. 8 makes it illegal to seek an abortion in Texas after six weeks. What impact has this had on women there?

Bridges: There’s no question that, at the time of its passage, S.B. 8 was unconstitutional under existing Supreme Court precedent. The authors of the law never argued that it was constitutional. They admitted that it was inconsistent with Roe v. Wade and with Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the 1992 decision that clarified the standard for evaluating abortion restrictions. Instead they intentionally inserted a quirk into the law: state actors don’t enforce it — private citizens do. Those challenging the constitutionality or legality of the law quickly found that they didn’t have anybody to sue.

Many people don’t discover they are pregnant before six weeks. And now no Texas health-care provider will perform an abortion after six weeks because they could face devastating financial consequences in terms of civil liability. In May Oklahoma passed a total ban on abortion. Meanwhile the number of abortions being performed in Kansas has been increasing because people from Texas and Oklahoma are going there to exercise their constitutional rights. Kansas clinics are overburdened. I’ve heard that the wait time for an appointment is four weeks or more. So people are being forced to carry unwanted pregnancies for longer periods of time, which is excruciating. If you ask anyone who has ever carried an unwanted pregnancy, every extra day is torturous.

And it’s only the lucky ones who are able to get an appointment before they reach twenty weeks, which is the cutoff in Kansas. After that, they can’t terminate the pregnancy there. And only people who have certain resources are able to travel out of state. They have a car; they can take time off from work; they have childcare secured; they’re not undocumented and living in a part of Texas where they have to cross an immigration checkpoint; they’re not in a violent relationship and have to hide their whereabouts from an abusive partner; they’re not young and have to hide their whereabouts from an abusive parent. The most marginalized are the ones being forced to carry pregnancies to term.

The U.S. Constitution is supposed to guarantee certain rights to everybody in the country. But this Supreme Court has allowed for a patchwork where the rights you possess depend on the state in which you live.

Moreno: And S.B. 8 can’t be challenged because there’s no clear person to be sued?

Bridges: Yes, this was an intentional feature of the law. It was designed to prevent any federal judicial review. And the Supreme Court allowed this gambit to work because the Court, as well as the Fifth Circuit, has been stacked with conservative jurists who find that sort of legislative machination tenable. But the law doesn’t demand this result. This is a political reading of what the law demands.

What the Supreme Court allowed Texas to do with abortion could apply to any constitutional right. Democratic California governor Gavin Newsom has announced that his state is going to do something similar when it comes to owning assault rifles. (There is no constitutional right to bear an assault rifle, but owning a handgun is a constitutionally protected activity.) Mississippi could do it with regard to same-sex marriage. Florida could do it with regard to practicing non-Christian religions. The U.S. Constitution is supposed to guarantee certain rights to everybody in the country. But this Supreme Court has allowed for a patchwork where the rights you possess depend on the state in which you live.

Moreno: This Texas legislation has been compared to lynching and other forms of vigilantism, where citizens take the law into their own hands. Do you agree with that comparison?

Bridges: S.B. 8 allows private actors to enforce a law, and we do have a long history of racist white private actors inflicting violence upon nonwhite citizens. And states in the South — Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana — have a long history of trying to subvert federal authority when it comes to the rights of people of color. They’ve always said that they have “states’ rights.” So if Georgia wanted to prevent Black people from voting, then it’s “states’ rights.” If Texas wanted to allow private actors to lynch Black people in the state — “states’ rights.” We’ve needed the federal government to come in and protect Black people when the states themselves wouldn’t. With S.B. 8 we’re back to this kind of political and legal situation where Texas can do whatever it wants to its vulnerable citizens, and the federal government is boxed out from protecting them.

When an expected consequence of a law is to disproportionately disenfranchise racial minorities, I’m comfortable calling that law racist. But if we were to start looking for racist actors in the Texas legislature and trying to figure out if bigotry motivated them to vote in favor of this law, I think that’s a losing battle.

We’re back to this kind of political and legal situation where Texas can do whatever it wants to its vulnerable citizens, and the federal government is boxed out from protecting them.

Moreno: We’ve seen governors, prosecutors, judges, and even a sheriff in South Carolina declare some level of resistance to enforcing a full abortion ban. How effective do you think this refusal to enforce can be in the long run?

Bridges: Police and prosecutors have a lot of discretion in terms of how they enforce the law. For example, say two people get into a fight on the street, and the police show up. The police are not obligated to arrest anyone; they have the discretion to make an arrest or not. It’s the same with prosecutors: as prosecutors get police reports, they have the discretion to file charges or not, to pursue an indictment or not. It’s always nice to see police and prosecutors exercise their discretion in a way that furthers justice, but it’s a sad state of affairs when we have to depend on their discretion to avoid criminalizing health care. Is it resistance? I think it is resistance. But it’s tragic that we even need them to resist in this way.

Moreno: There are fears that anti-abortion groups could turn their focus to embryos created for in vitro fertilization, or IVF. Do any legal precedents suggest what would happen there?

Bridges: I don’t know. I haven’t thought much about assisted-reproductive technologies. I suspect IVF will remain safe because it’s a billion-dollar industry with very powerful people behind it, and I think they will be able to leverage their power politically. And the folks who turn to IVF are some of the most privileged people in our society. If history is any teacher, privileged people will always be able to exercise their privilege.

Moreno: I don’t have a legal background, but it’s my understanding that there are some who view the law in terms of philosophy, and there are others who view the law as literal. Where do you fall on that spectrum?

Bridges: I think what you’re asking about is “textualism” — the most literal reading of the wording of a law — versus the need to interpret legal texts like the Constitution in light of new developments in society. I’m definitely not a textualist. Words are often ambiguous and have to be understood in light of context, in light of intention, and in light of society’s needs. For example, the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment says that no state shall deny a person “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” What does it mean to deny somebody “life”? Does it mean that the state cannot physically kill them? Or are we talking about life more expansively, as in “My life is full. I love to dance, I love to write, I love to spend time with my family.” In that context depriving me of my relationship with my husband or the ability to dance might mean depriving me of life.

It’s the same with “liberty”: Are you talking about liberty in terms of detaining someone in some sort of jail or other institution? Or are you talking about liberty in terms of the ability to do the things that I love on a daily basis? So I don’t think textualism can achieve the aims of those who authored the law. And I don’t think textualism allows us, especially with very old texts like the Constitution, to meet the needs of a society that is vastly different from the society in which the framers were operating.

An “originalist” view tries to interpret the Constitution in light of what people thought the Constitution meant when it was written or ratified. If you do that, you freeze our protections at a time when a whole lot of people weren’t members of the body politic. Women weren’t considered full citizens at the time the Constitution was ratified. Black people were considered property. Native people were considered killable. Trans people were completely erased. Gay and lesbian and bisexual folks were criminalized. To interpret the Constitution in light of what people thought in 1789 — or 1868, when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified; or 1973, when the Roe v. Wade decision was made — is to diminish the protections offered by the Constitution; to interpret it in light of values that we’ve rejected. And, to be clear, originalism is often embraced by those who want to achieve particular political outcomes. It is embraced for that very purpose.

The five justices who signed on to the majority opinion overturning Roe v. Wade are not purists when it comes to this method of interpreting the Constitution. They deploy this method when it’s useful to them because it will produce a particular result. I tell people: Look for this Supreme Court’s decision next term when it hears the affirmative-action case Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard. Be on the lookout for an absence of any investigation into what people were thinking in 1868, when the equal protection clause was written. Because if you interpret the Constitution in light of what people were thinking in 1868, then you have to admit that the Constitution permits race-based affirmative action. After chattel slavery ended in the United States, there were race-based efforts to ensure that Black people had equal citizenship. So it seems clear that an originalist interpretation of the equal protection clause would lead to the conclusion that affirmative action is permissible. But I predict originalism will not make an appearance in the affirmative-action case next term, because it does not lead to the political results that the majority on this Supreme Court wants.

Moreno: Do you see the framework of the law, or the concept of the law, as holding any hope for the future of reproductive rights in this country?

Bridges: The law is incredibly capacious. It’s capable of achieving justice, but it has also been very good at producing unjust outcomes. A question about the law is a question about politics. It’s a question about who has the power to interpret the law and to make the law. Polls show that a majority of Americans support abortion rights. I believe most Americans, at least in theory, value people’s ability to control what happens to their body and the trajectory of their lives. Whether our laws will reflect this is a question of whether people are going to be able to elect lawmakers who reflect their values. It’s a burning question about whether we in the United States are going to have a democracy. Because dozens of states are vigorously disenfranchising voters, and the Supreme Court is doing nothing to stop it. I’m hopeful that the U.S. will remain a democracy, and if democratic processes govern, then the law will come to reflect the values that most people have regarding reproductive rights. But it can always go the other way, cementing minority rule. If that were to happen, then we shouldn’t expect any positive developments when it comes to reproductive rights and reproductive justice.

Moreno: What is the difference between reproductive rights and reproductive justice?

Bridges: The term “reproductive rights” has been bandied about since the 1970s and has become synonymous with a narrow focus on the right to terminate a pregnancy. And by that I mean: the government can’t take away your ability to purchase abortion services in the market. The term “reproductive justice” was generated by feminists of color in the 1990s. It includes the right to terminate a pregnancy, because that’s super important, but it also includes the universe of other reproductive issues we ought to be concerned about if we want people to be free from oppression. Reproductive justice means access to abortion and contraception, but it also means the right to have a child. It means the right to be free from coerced sterilization; the right to have access to health care to help overcome infertility; the right to be free from environmental degradation that makes it difficult to carry a pregnancy to term and produces miscarriages and stillbirths. And it means the right to parent the child you have with dignity, which requires a healthy environment, violence-free neighborhoods, and support in terms of food, clothing, housing, and health care. Reproductive justice is much more expansive than reproductive rights.

Moreno: Before Roe v. Wade, how much control did women have over their fertility?

Bridges: Women with privilege have always been able to safely terminate pregnancies, even when abortion was illegal. Before Roe v. Wade, folks with class privilege were terminating pregnancies with private doctors with whom they had a relationship. They were able to travel to countries where they could terminate their pregnancies safely. The “back-alley” abortions — terminating pregnancies with coat hangers and the like — were largely for underprivileged people, poor people, people of color. In this post–Roe v. Wade world we are living in, people with privilege will continue to be able to terminate their pregnancies safely, if not always legally. And those who don’t have privilege will be forced to try to terminate pregnancies under unsafe conditions. I also think it’s important to know that if we make it a crime to terminate a pregnancy, we can expect people of color to be disproportionately arrested, disproportionately indicted, and disproportionately convicted, and to receive longer sentences for violating the law. How do I know this? Because tons of studies have shown that if a white kid and a Black kid both get caught with an ounce of marijuana, the white kid is more likely to get to go home, and the Black kid is more likely to be arrested, indicted, and convicted. And even if both are convicted, the Black kid will serve a longer sentence for the same criminal behavior. The research on this is indisputable.

Moreno: Is criminalizing abortion a stepping-stone to reduced contraceptive access?

Bridges: The Roe v. Wade decision was built on a couple of cases that came before it: Eisenstadt v. Baird in 1972 and Griswold v. Connecticut in 1965. In both cases the Supreme Court interpreted the Constitution to protect the right of an individual to access contraception. And then Roe v. Wade came along and said that the right to privacy, upon which the right to access contraception is based, is broad enough to protect the right to terminate a pregnancy. So if Roe v. Wade is not good law, as five Supreme Court justices have claimed, what makes Griswold and Eisenstadt good law? Where does it stop? Are those cases also improper interpretations of the Constitution? If so, then people will no longer enjoy a constitutional right to access contraception in the marketplace. Texas might ban birth-control pills and IUDs, and this Court could permit it.

We know Justice Clarence Thomas thinks that Griswold and Eisenstadt were improper decisions. He’s been very clear that he believes the right to privacy is nonsense. The question is: How many other justices agree with him? When Amy Coney Barrett was questioned during her confirmation hearings, she refused to state that Griswold and Eisenstadt were proper interpretations of the Constitution. Neil Gorsuch also refused to state that he believed Griswold was properly decided. Three of the nine justices have publicly articulated their position that the Constitution does not contain a right to privacy — at least, when it comes to matters involving contraception. It’s wild that we’re in a moment when a third of Supreme Court justices are willing to throw out a half century of constitutional law. And that’s just the three we know about. Justice Alito is one of the most conservative jurists on the Court right now. And Justice Roberts is a wild card. We’re not in a good place when it comes to the Court protecting rights we assumed would always exist.

We’re living through so many scary moments right now. The gutting of the Voting Rights Act and what Texas, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, and so many other states are doing to disenfranchise nonwhite voters — that’s terrifying to me. Sometimes I want to bury my head in the sand and have somebody tell me when it’s safe to come up, because paying attention makes for some sleepless nights.

Moreno: How does the U.S. compare to other countries in terms of reproductive rights?

Bridges: Most countries are liberalizing their abortion laws. Mexico recently had a huge win in terms of expanding access to legal abortion. Ireland, a majority-Catholic country, recently expanded access to legal abortion. Meanwhile the U.S. is choosing to dramatically reduce or eliminate abortion. That makes us a bizarre outlier among industrialized nations. Most nations we like to call our peers have generous paid parental leave for both parents. No industrialized nation, besides the U.S., provides zero paid parental leave. We should be embarrassed. We should not be regressive when it comes to supporting pregnancy and parenting. Instead we should be trying to exceed what our peer nations are doing.

Moreno: You mentioned a constitutional right to privacy. It seems that women, especially poor pregnant women, have been consistently denied the right to privacy. What argument is used to justify that?

Bridges: No one will explicitly come out and say, “Poor people don’t have privacy rights,” but we’ve created a landscape where poor people don’t have a right to privacy in any real sense of the word. For example, I can go to my private doctor and get the care I need and be home within thirty minutes. Poor people don’t have that luxury. In order to get state-funded prenatal care in the state of New York — and this is true in Illinois and California as well — before you even see a provider to assess the health of your body and your fetus, you have to see a social worker, a financial counselor, a health educator. All of these professionals require you to give very intimate information about yourself. And it’s not strictly medical information. They want to know who you live with, how’s your relationship with the father of the fetus, what’s his earning capacity? This is intimate information that privately insured people never have to give in order to get health care. And if a poor person declines to give that information, they can expect to be investigated by Child Protective Services, because it’s assumed that they have something to hide. Child Protective Services predominantly polices poor people. People with class privilege rarely find themselves investigated or have their children taken away.

Moreno: How else are poor people deprived of their privacy rights?

Bridges: When you’re poor, you’re regulated by the systems that provide you with public benefits. Poor people have the state in their lives at all times. Those who need to rely on the state for basic necessities — food, clothing, shelter, health care — have no privacy rights. In this country we require you to exchange your constitutional rights for those necessities.

I teach a case called Wyman v. James, which more people should be familiar with. It’s a 1971 case in which the U.S. Supreme Court upheld warrantless searches of welfare recipients’ homes in the state of New York. The idea was that if you received welfare benefits, you had to allow some state actor to come into your home and look around. What are they looking for? They’re making sure you aren’t lying about your need to receive welfare benefits or abusing your kid. Those sound like pretty good reasons to allow someone to come into your home, right? But one problem with this is that the Fourth Amendment prohibits the state from conducting unreasonable searches and seizures. A long line of legal precedent says that in order for the state to search you, either you have to give consent or there has to be probable cause and a warrant. But in this case the Supreme Court allowed for warrantless, nonconsensual searches of people’s homes simply because they were receiving welfare. Can you imagine the outrage if Fox News viewers thought the state was going to come into their homes without their consent and without a warrant just to look around and make sure they’re not lying about anything or abusing their kids?

Though we should definitely protect children from abuse and neglect, the reality is that poor parents aren’t the only ones abusing and neglecting their kids. Wealthy parents abuse and neglect their kids, too. But nobody’s coming into their homes without warrants or consent to look for evidence of abuse and neglect. We’re only doing that to poor people. Either search everybody’s homes or search nobody’s home. That’s what equality requires.

Poor people are not the only ones who receive assistance from the government, but they’re the only group I’m aware of that has to cede claims to privacy and dignity and autonomy in order to receive that money. Farmers receive incredible amounts of money in subsidies. The government pays them not to grow certain crops or subsidizes the crops they do grow. I’m not arguing that they don’t deserve the money. I’m just observing that farmers receive these subsidies without having to let the government into their homes to check out the bathrooms and the garbage cans.

I have mortgages on two homes that I own. I pay interest on those mortgages, and the government is kind enough to offer me a tax deduction on the mortgage interest that I pay. Never has the government knocked on my door and asked to look around the houses on which I’m claiming the mortgage-interest deductions. Never has the government asked, “How many people are living in the house? Are all the bedrooms occupied? Did you convert one bedroom into an office?” The government doesn’t ask me any prying questions about my homes before allowing me to take this mortgage deduction. Differently stated, the government does not invade my privacy simply because it is giving me a benefit. This is solely because I’m not poor.

I can go on and on about the myriad ways that the government gives money to people with privilege without requiring some exchange of privacy and dignity. The only reason we require those exchanges of people who are poor is that we think there’s something wrong with them. I really appreciate my mortgage-interest deduction, but I don’t need it. If I had to pay thousands more in taxes at the end of the year, I’d be OK. But poor people need what the government is providing. And in exchange for having those basic needs met, they’re required to do things that wealthy people aren’t. There’s something perverse about that.

Moreno: There’s this perspective that privacy rights are conditional on the possession of “good moral character,” which seems like a very subjective judgment to place in the hands of a government entity. How is “good moral character” determined, and who has the authority to determine it?

Bridges: In this country we equate morality with money. We think wealthy people are good people. We think wealthy people are kind of awesome, in fact. They’ve succeeded at capitalism, right? They are economically self-sufficient. At the same time, we think poor people are poor because there’s something morally wrong with them: They’re lazy. They don’t have a good work ethic. They have unprotected sex and have babies out of wedlock. They are criminally inclined. That’s how we explain poverty.

But the real explanations are structural. For example, we have inhumane immigration laws that require people to be undocumented for long periods of time, which allows them to be exploited by employers who can pay them a pittance. We solve our social problems by putting people in prisons and jails, which impoverishes their families and communities. People are poor because we don’t provide them with health care. People are poor because we don’t provide adequate schools for them as children. And so on. We could embrace a structural explanation of poverty, one that doesn’t blame poor people for being poor. Instead, as a country, we embrace these individualist explanations of poverty. If we’re talking about poor parents specifically, we are inclined to be skeptical of their ability to competently raise a kid. We assume they are not only incompetent but possibly a danger to their kids. We see them as criminally inclined, devious.

This baseless perspective goes a long way toward explaining why we subject the poor to such surveillance and regulation. You asked who determines who has a “good moral character.” These cultural narratives, which have existed for a very long time in the U.S., are a big part of what determines it. The only way we are going to embrace a structural explanation of poverty — and pass laws that reflect it — is with a cultural transformation. We need to reject the old narratives that explain poverty in terms of individual shortcomings.

Consider this example: We fund schools through property taxes. The property-tax base is low in poor communities, so they have less money for education. If we adequately funded schools and made sure they had decent buildings, and teachers who were well trained, and iPads in every room, and other opportunities, then the kids who graduated from those schools would have more skills, and their talents would be supported. They would be better able to earn an adequate income. Is that a welfare program? It doesn’t involve giving out individual benefits. It’s actually a societal commitment to eradicate structural racism by changing the way we fund public schools. That’s just one example, but I can imagine many ways of addressing the structural roots of poverty as opposed to trying to “fix” poor people.

Moreno: So we need a redistribution of property-tax money?

Bridges: Absolutely. We’ve made a choice to fund schools in terms of local property taxes, but we could just as easily fund them through property taxes at the level of states and distribute the funds that way. We have made a choice to allow wealthier neighborhoods and communities to fund their schools through taxes on their incredibly high-value properties.

Moreno: You refer to the specific scrutiny and surveillance placed on poor mothers as “new-school racism.” Could you talk about how that manifests?

Bridges: When I describe how Medicaid invades poor people’s privacy, people often assume that Medicaid is classist, as opposed to racist. But it’s important to see class and race as connected. In my scholarship I’ve described the systems we have designed for the poor as having a “racial salience.” When we think of poor people in this country, we think of people of color. There’s a political scientist, Martin Gilens, who has shown that the more welfare became associated with Black people, the more people in this country hated welfare. The systems we have designed to care for poor people are racialized in the sense that most people in this country think those systems are for people of color, for Black people. Our dehumanizing treatment of poor people is a function of our dislike of people of color. So if the Medicaid system invades poor white people’s privacy, it’s because those poor white people are caught up in systems that were designed for people of color. Poor white people should be just as interested in racial justice as people of color. They are denied their humanity, their privacy, because they are swept up in systems that are racist.

Moreno: Your research focuses on pregnancy as a “racially salient” event. Can you describe what racial saliency means?

Bridges: We don’t think of pregnancy without imagining the person who is pregnant. And how we value that pregnancy — whether we think of that person as worthy of pregnancy — depends on race. For Latinx people pregnancies have become associated with stories of undocumented immigrants giving birth and making claims on the state in the form of citizenship or welfare benefits. When Black people are pregnant, they are associated with the “welfare queen” — someone who is having babies in order to make claims for welfare assistance. When white people reproduce, they don’t have those negative associations. Their pregnancies tend to be celebrated as good, if not for the nation, then at least for them and their families. This absence of negative stereotypes attached to white pregnant bodies shows that pregnancy is a racially salient event.

I’m conducting research for a new book right now, and what I’ve found is that Black people, even those who have class privilege, know that Black reproducing bodies are valued differently. Black pregnant women try to perform their class privilege so that people don’t think of them as some welfare queen. Black women will refuse to take off their wedding rings during pregnancy, for example, so that the doctors don’t perceive them as unmarried. They try to secure good health care by performing class in ways that white women wouldn’t.

Moreno: In one of your books you describe yourself as being in the awkward position of criticizing the push for universal health care while also being a proponent of it. You are particularly critical of the surveillance that accompanies universal health care. Some would say the alternative to this surveillance is for disenfranchised populations to have no health-care access at all.

Bridges: New York State has one of the most generous Medicaid prenatal-care programs in the U.S. The health care that it provides during pregnancy is comprehensive. You can get your eyes checked. You can get dental work done. But that generosity has a whole bunch of strings attached. If you’re pregnant and poor in New York, you lose your ability to determine how you conceptualize your pregnancy. Many people, including health-care providers, conceptualize pregnancy as a completely healthy state of the body that doesn’t require constant scans and measurements and blood tests. Under New York’s Medicaid program, however, patients are not allowed to pursue the vision of pregnancy and prenatal care that aligns with their values.

I can critique those aspects of Medicaid while also recognizing that it would be awesome if all states decided to provide the health care that New York provides for its residents. We’re in the midst of a sociopolitical moment in which conservative forces are fighting — and often winning — a battle to claim that the government has no obligation to its citizens at all. When you have one of only two political parties saying that the government ought not to provide health care to anybody, it becomes awkward for me, a person who believes in universal health care, to critique the measly health-care systems we do have. But my critique doesn’t lead to the conclusion that we should get rid of Medicaid. My critique leads to the conclusion that we need to make Medicaid better. We need to make it respect people’s humanity and their dignity and their autonomy.

Moreno: Do you think it’s possible for a system to prioritize both patient health and patient privacy at the same time? What would it look like?

Bridges: Oh, absolutely. We already have such a system in place. It’s called private insurance, and it looks like what I experience when I go to the doctor. If I were pregnant, I could choose a provider who would draw my blood every day, weigh me every other day, and scan my fetus for genetic anomalies. Or I could not see anybody for the first three months, because I don’t think pregnancy requires medical oversight during that time. I could choose a doula and a midwife and finagle myself a home birth. I could do that because I have class privilege. And even if my insurance refused to cover that, I could pay out-of-pocket.

It’s a burning question about whether we in the United States are going to have a democracy. Because dozens of states are vigorously disenfranchising voters, and the Supreme Court is doing nothing to stop it.

Moreno: You quote some statistics in your writing about the higher infant and maternal mortality rate among Black people. What are some factors that cause these increased mortality rates?

Bridges: Black women die at three to four times the rate of their white counterparts from pregnancy-related causes. Black babies die at twice the rate of white babies. Why is that? Where do I begin. We have a segregated health-care system, divided between the haves and the have-nots. The haves receive private insurance; the have-nots receive Medicaid, which doesn’t reimburse at the same level as private insurance. This means doctors and facilities receive less money to provide for Medicaid patients, making it impossible to give them equivalent care.

It’s also important to recognize that these racial disparities in infant and maternal mortality persist across income levels. Wealthier Black people are dying at higher rates than wealthier white people. This isn’t a problem of class as much as it is a problem of racism. Environmental injustice is killing us. The neighborhoods that people of color call home are often more polluted. They are the sites of landfills and factories and industrial plants. They tend to be next to highways and have poorer air quality. They tend to have lead in the soil and the paint. Environmental injustice contributes to Black infant and maternal mortality.

Racism itself has deleterious effects on people’s bodies. Public-health researcher Arline T. Geronimus theorized decades ago that the physiological effects of racism-based stress age organ systems. She called it “weathering.” People of color have higher rates of hypertension, kidney disease, diabetes, asthma, and heart disease not because there’s something inherently wrong with us, but because we’re living in a hostile environment, and that hostility is having a negative effect on our bodies.

Moreno: In your book you talk about physician racism and medical racism, which are different concepts. Are both related to the high morbidity rates of Black patients? And how did physician racism manifest in your research?

Bridges: My thinking has evolved over the years, and I’m currently less interested in the phenomenon of physician racism. I do think physicians’ implicit bias explains some of the poorer health outcomes that people of color have, but I’m not going to spend my time looking for biased physicians, because I don’t think racism in this country can be reduced to racist individuals, even though they exist. What’s really doing the heavy lifting when it comes to racial disparities in health are processes and systems and structural issues that are race-neutral on paper but have horrible racist impacts in reality.

I am, however, super interested in medical racism — how medicine promotes racial inequality. There’s still a medical embrace of the idea that Black people’s bodies are fundamentally different from white people’s bodies, which are fundamentally different from Asian people’s bodies, and so on. This idea rears its head everywhere. Recently the National Football League was using a “race correction” when evaluating concussions: Black players had to show lower cognitive function than white players in order to get a payout from the NFL. Why? Because medicine said that Black people’s brains operated on a lower level to begin with. This was in 2020 and 2021! Black people also have to show that they have lower lung function in order to qualify as having certain diseases of the lungs, because the belief is that Black people’s lung function is just not as good as white people’s. Same thing with kidneys.

When medicine normalizes this idea that Black bodies are just different from white bodies, then it normalizes inequality. It normalizes the idea that some people live longer lives and are healthier than others as a function of their race. This is something we should all be in the streets protesting about.